Lit Mags

Videos of People Falling Down

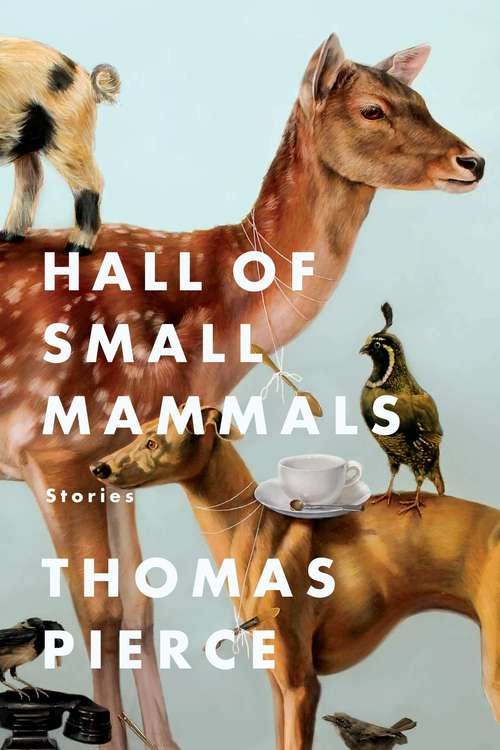

by Thomas Pierce, recommended by Riverhead Books

EDITOR’S NOTE BY LAURA PERCIASEPE

When I first encountered Thomas Pierce’s writing, it set off quiet and powerful earthquakes in my brain. His stories have the power to bring you immediately into their world, and then turn you upside down, sideways, and transformed. Reading his manuscript for the first time, I felt the tension and anticipation (and greediness) that an editor feels when they know… this is one I must publish. This is a voice that needs to be delighted in, needs to be heard.

Everyone who has read Hall of Small Mammals — the collection which includes this story — has confided in me that, of course, this story or that story was the best one, the stand-out of the collection. And it would always be a different story. Every story in this collection is someone’s favorite, including this one, “Videos of People Falling Down.” I hadn’t ever seen this reaction before, and it speaks to the incredible diversity and brilliance of Thomas’ writing. The striking thing to me was this sense of intense ownership and kinship readers felt with Thomas’ work. They came into his world and felt like it was their own.

A powerhouse of inventiveness and imagination, “Videos of People Falling Down” is structured like a symphony that plays back on itself, building to a crescendo of emotion and experience. When Thomas and I were editing the story, we had charts and lists of characters and long discussions about who and what and why. We kept talking about it as a puzzle that needed to fit all together; that’s the technical stuff, but the stuff that sucks you right in is the humanity of this piece and Thomas’ artful storytelling.

This story is about the interplay of a group of people. Their connections are revealed, their personalities exposed. It’s also about our personal failings, our falls, and how they’re captured and replayed in modern society (and in our own minds) over and over, becoming a part of the cultural fabric. Searing and playful images and motifs run throughout: a woman who falls into a polar bear habitat at the zoo, a book about beekeepers, a murderous cellist, Brahms’ “Hungarian Dance No. 5.” I played that song on my violin as a young girl and when I saw it in this story, I could hear the melody in my mind. It was a personal, emotional link to the storytelling, something that Thomas has an uncanny way of bringing out for every reader, making his collection both universal and still very intimate.

Enjoy this story — perhaps it will be your favorite story — and to find out more about this wild and wooly world of Thomas’ writing, read his book, Hall of Small Mammals.

Laura Perciasepe

Editor, Riverhead Books

Videos of People Falling Down

Thomas Pierce

Share article

by Thomas Pierce, recommended by Riverhead Books

How NOT to Ride Down Stairs HUGE FALL

A boy with floppy brown hair and freckled arms pedals his mountain bike toward some concrete steps outside of a high school. There are twenty-five steps, and they lead down to the teacher’s lot. The boy’s friends are waiting at the bottom to see what happens. When he reaches the first step, he leans back in his seat to keep from toppling over the handlebars. His name is Davy, and he can draw a hand perfectly. Nobody draws a hand like Davy. His art teacher wants him to apply to art schools next year. She believes one day Davy will draw not only a perfect hand but also a perfect wrist and a perfect arm and, if he is diligent, a perfect shoulder too. Beyond that she dares not hope. Necks are the most beautiful part of the female body, and no one has ever captured one as it really is.

The art teacher possesses a neck more elegant than most. If it wasn’t indecent, she’d pose for Davy. At the moment of his stunt, she is locking up her room, a box of school-bought art supplies under her arm. She doesn’t see Davy fall, but she’s the first adult on the scene. Davy is conscious, on his back across the bottom three steps. She orders him not to move an inch. The bone has punctured the pale skin of his left arm. She calls the ambulance and follows it all the way to the hospital in her beat-up Acura. In the emergency room, she finds a seat beside a big man whose leg is wrapped in a bloody towel. The teenager to her right doesn’t cover his mouth when he coughs. She flips through a Golf Digest. The old woman across from her is reading a novel with bees on the cover. “What happens in it?” she asks the woman, and the woman says, “Two beekeepers fall in love but it’s impossible for them to be together.”

Old Woman FALLS into Polar Bear Habitat

The book about beekeepers is Now a Major Motion Picture starring Julia Roberts. “Swimming,” one of the songs on its sound track, has become very popular on the radio. The song was written and performed by Simon Punch, a whisper-voiced guitarist with a hip Rasputin beard and a long thumbnail painted black, and the lyrics are based on something that happened to him as a boy at the zoo with his grandmother.

They were watching two polar bears paddle around in a clear blue pool when she leaned too far over the concrete wall for a photograph and fell eight feet down into the water. Simon was too young to do anything but watch as she splashed and screamed, scraping at the wall like a lunatic. A crowd formed. A man dangled his jacket down to her and she grabbed hold of it. Because she wasn’t strong enough to hold on for very long she kept plunking back down into the water. A lady who worked for the zoo ran over with a bucket and tossed fish parts into the pit to keep the polar bears distracted, but one of the bears lunged and bit his grandmother’s leg. When she finally emerged over the concrete wall — dripping wet, bleeding, embarrassed — they ripped away her pants and discovered that the bite wound, thank God, wasn’t life-threatening. Still, all these years later, Simon sometimes dreams about polar bears. They come after him with impossibly large teeth and suffocative fur. They chase him down streets and up stairs — to the perimeter of his dreams. When he wakes he can feel their chilly wet breath on his neck.

Stupid People Falling Ouch Try Not to Laugh

A man is on his way to meet a friend for a late drink and stops at an ATM for some cash. His wallet is ridiculously fat — not with cash but with movie stubs, wads of receipts that he will never actually sort, a photo of his wife, a photo of his long-dead basset hound, and all his cards: the Anthem insurance card, the library card, the one-year pass to the contemporary art museum, and of course his many credit cards. The bank is closed for the night. The lights are off in the main lobby. The ATM is not directly on the street but in a small glass anteroom. Accessing it after hours requires that you slide your bank card into the slot by the door.

The man inserts his card, and a tiny light above it flashes red three times. He inserts his card again and pulls it back out more deliberately. The light blinks red again.

His name is Marshall, and he manages a nearby stationery shop. He is also an accomplished cellist. He is third chair in the city symphony. His favorite composer is Brahms. Sometimes when he hears “Hungarian Dance No. 5” he has a funny feeling that is difficult to explain to others. He’s told only one or two people about it. The feeling involves the possibility of a past life.

Through the thick bulletproof glass, faintly, Marshall can hear music playing — not Brahms but something else. It’s that Simon Punch song, he realizes, the one from the Julia Roberts movie about beekeepers. He consults the pictogram on the card reader to make sure his card was properly oriented. He rubs the magnetic strip back and forth across his pleated khakis to make sure it wasn’t dirty and then he inserts it again. The red light flashes. Maybe something is wrong with the reader or with the ATM behind the glass. Maybe it’s out of order and the bank forgot to hang up a sign. A woman with jangly gold earrings approaches with clacking cowboy boots.

“Let me guess,” she says. “Broken?”

“Might be,” he says, and steps aside so she can try her own card.

Her card is silver. She slides it in the slot and pulls it back out hard and fast, and when it flashes red, she does it again, hard and fast. Marshall can’t help drawing certain conclusions about this woman. He pictures the woman naked and on top. The light flashes red, red, red.

“What a piece of shit,” she says. The woman looks to be in her forties. She taps the bottom of the door with her stiff boot toe. She has on way too much mascara. It’s like her eyes are at the back of a dark cave. “There’s another machine around the corner outside a liquor store,” she says, “but it’ll charge you a hundred dollars practically.”

“If it’s broken, they should have put out a sign,” he says.

“I only need like ten dollars.”

If he had ten dollars, Marshall would give it to her. They stand there, peering through the glass for a few more moments, the traffic moving lazily behind them on the street. Marshall imagines throwing something at the glass, shattering it, the two of them stepping through together triumphantly.

The woman pushes at the door without sliding in her card at all. It opens, magically. The red light was meaningless; the room was unlocked all along. They roll their eyes at each other: Of course it was open! She goes in first, and he waves her toward the machine. He says, “Be my guest.”

“I’ll be quick,” she says. He waits a few feet behind her. This isn’t a large space, and he could see her screen if he wanted. When the ATM spits out the woman’s money, she turns to him and holds up her receipt, victorious.

She leaves, and Marshall inserts his card, punches in his number, and selects the fast cash option. The machine buzzes and the money pops out and the receipt curls toward him. He checks it quickly, then looks again. His account balance, it’s very low. Thousands of dollars are missing.

Susan. This has to be Susan’s doing. She recently moved out. “Temporarily,” she said. It was a total shock. Sure, they argued — about the way he drags his feet when he walks, about who it was that forgot to recork the red wine before bed — but this made them no different from any other couple.

Susan said she was going to stay at her sister’s place, but he suspects his wife has a lover. That’s the only way to explain it.

When Marshall called Susan’s sister, she said Susan was in the bathroom, but when his wife returned his call later that night it was from her cell phone and there was strange dance music in the background. She was at some kind of party, obviously drunk, and all she wanted to talk about were tiny chairs. She could barely hear him. She wasn’t answering his questions. It was infuriating.

“Enough with the Brahms,” his wife used to say.

Many years ago he told his wife how he feels hearing “Hungarian Dance No. 5,” about that hazy cloud that descends, about the cascade of images both familiar and unfamiliar, a long dusty street, a distant flat mountain, ships on a waterfront, white horses and carriages, a ten-story hotel with ornate columns and a large gold clock in the lobby, a bag over his shoulder, a beautiful woman in a maid’s outfit, a bustling kitchen, a pantry with white shelves full of food, the light sneaking under the door, the woman’s dress raised high, her legs spreading to receive him, the flour spilling onto their shoulders, her breath hot in his ear. “That’s not a past life,” his wife told him, “that’s historical porno.”

Marshall examines the receipt as he turns away from the ATM. His wife, who hasn’t even collected all her clothes from their closet yet, has basically robbed him. He can think of no other word for it. She’s stolen his money; she’s going to strange tiny chair parties; she’s sleeping in another man’s bed.

Marshall has forgotten that he is enclosed by glass. When he runs into the glass wall, it doesn’t shatter or crack — but wobbles. He falls back onto the floor. One palm lands on the greasy white tile, the other on the dark rubber mat with the bank’s insignia. The receipt is on the ground in front of him. There’s a tiny camera in the ATM and another security camera looking down on him from the top right corner of the room.

Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Man Falling Down

Among Thomas Edison’s earliest films you will find footage of zooming trains, electrocuted elephants, boxing cats, and a snuff-induced sneeze. Surely an early documentation of a falling man comes as no surprise. There had to be a first. The footage is grainy, and the frames skip. The man is one of Edison’s assistants. Until they tripped him with a wire, he was under the impression they were making a film called Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Man Jumping Up and Down. Falling down has never been the same. Now we can watch the same fall a hundred times. We can laugh at it. We can study it. We can slow it down. We can speed it up. We can linger on a single frame. We can see the birth of fear and panic in a human face. We can identify that moment when a person suddenly realizes that he is no longer in control of what happens next. But the simple truth is that we are never in control of what happens next.

Falling down is the universe being honest with you, finally. It’s life as it really is.

This occurs to Marshall as he walks home from the bank, his plans canceled, an ugly bump already bulging on his forehead. His wife is out for the night, no doubt, probably having the time of her life with all their money, and he will spend the rest of his evening with a bag of frozen peas pressed to his head, like an idiot. He feels like throwing a rock at the canoodling couple across the street. He wants to kick the cat that darts across his feet on the stoop. That airplane overhead, the little flashing dot of light, he wishes it would come crashing down out of the sky and just put him out of his misery, kaboom.

People Falling on Snow/Ice Funny!!!

Twenty-two thousand feet overhead, Beth is on her way out West. When her seatmate leans toward her and says his name is Randolph, she laughs.

“What’s so funny?” he wants to know.

“Nothing,” she says, embarrassed, hand rising to her mouth. She’s never been the giggly sort. Her father used to call her his Gloomy Little Mac-Beth. She wonders if it’s possible her seatmate is having this effect on her. “I’m just excited,” she says. “That’s all. I drank too much water or something. Maybe it’s the air pressure.”

The man has a white linen pocket square in his sports coat and some kind of gel product in his brown hair that makes it shine. He’s in the window seat and he has his shoes off, one socked tumescence rubbing the other. She tries not to examine his feet. Through the porthole the darkness is interrupted every few seconds by the flashing bulbs on the wing. Sometimes the wings appear to wobble, a fact she finds very disconcerting.

“Let me guess,” Randolph says. “A ski trip.”

“Snowboarding, actually,” she says. The trip is an early graduation gift from her mother. Beth is meeting a friend at the airport. In a few months Beth will have her B.A. in sociology. Her thesis is a case study of frequent-flier programs. According to her laptop’s “find” function, the term sociotechnical appears in her paper seventy-three times. Though she has studied frequent-flier programs, Beth does not belong to any herself. She doesn’t find this fact ironic, as she has flown maybe three times in her entire life, present flight included.

“I do development,” the man says. “For a children’s hospital.”

She nods politely, too politely, and the man unloads about the latest capital campaign, how they’re trying to raise $5.2 million, and how he’s close to getting it — so, so close. Fingers crossed he’s lined up a very famous actor to help raise the last few million. She asks him what actor, and he says he shouldn’t reveal that yet, but then nuzzles close and whispers, Skeet Ulrich. “I’m sorry,” she says, “who?” He gives her a wounded look.

When the plane lands, they stand up too early, together, and have to hunch beneath the bins. “Well, it was nice to meet you,” she says when they start to move, but then there’s another delay, and he says, “We’re never going to get out of here, are we?”

“There must be some kind of way out of — ” she says but doesn’t finish the lyric because the line is moving again.

They part ways in the terminal, but she sees him again at baggage claim. Before wheeling away his roller suitcase, he tips an imaginary top hat to her. When her bag shows up, Beth takes a bus to the rental car office. Amy, her friend since grade school, is already there with the keys. The drive to the resort is almost two hours. They talk about the end of school and the drugs they’ve never tried but might still and all their friends who are already engaged and how statistically at least three of those friends will be divorced within five years. They eat gross fast food on the way into town, and by the time they check in to their condo, it’s after ten but feels more like one A.M.

The next morning, amazingly, she spots Randolph at the bottom of a slope. She taps him on the shoulder and says, “Good morning, seatmate.”

“What are the chances?” he says. “I’m surprised you recognized me in this getup.”

His sunglasses are up high on his forehead. He wants to catch the next lift with her: then, he says, they can be liftmates too. The joke seems to embarrass him. Beth doesn’t know where Amy is, but they don’t have plans to meet up, until later at the lodge for lunch. “Sure,” she says, “why not? I can do another run.”

They ride the lift together to the top of the mountain, the metal parts creaking, their legs dangling over the white. “See you at the bottom,” he says at the top and shoves off with his poles. He skis very fast. He might be showing off for her. She has trouble keeping up with him on the snowboard, cutting back and forth through the powdery snow, but she tries her best. She’s moving faster than she ever has before. I’m a gazelle, she thinks. I’m a gazelle gazelle gazelle… She’s moving so fast she can hardly hold on to that one simple thought. She almost collides with another snowboarder but she doesn’t fall on the slope.

Her fall comes later in the evening as she and Randolph — still together — are descending a short wooden staircase outside one of his favorite restaurants in town. The steps are icy. She comes down on her right knee and right side. Her jeans are wet and grimy now. Possibly her foot is broken. As Randolph helps her stand, his arm under her arm, she sees a kid across the street in a lime green parka, his cell phone’s camera eye aimed directly at her.

“Try walking on it,” Randolph says. “Just walk a little.”

She hobbles around in a circle. It’s not as bad as she thought it was. It might just be a sprain. She has her arm draped over his shoulder now. They go inside together. He’s made a reservation for two. After sharing a dessert, both of them a little tipsy from the wine, he confesses that Randolph is actually his middle name, and if she’d rather, she can call him Arnie.

“Hello, Arnie,” she says, and giggles again. “I’m sorry. I don’t know why I’m laughing. I’m not usually like this. I’m not. I think it’s possible that I’ve been overserved. Is that possible? I’ve lost track.”

Funniest Thing You Ever Seen — Drunk Guy in Convenience Store

Lots of people fall down drunk.

Marshall, the cellist, is in the 7-Eleven next door to the stationery shop that he manages. It’s a little after midnight. The bump on his forehead healed a few days ago, but his wife, Susan, hasn’t been home in all that time. She won’t even return his calls about the missing money. He roams the aisles in search of snacks and cheap wine, dragging his feet, in a daze. He slips in front of the fridges.

“You all right?” the cashier asks, worried he might have left a puddle with the mop, worried about a lawsuit.

The cellist grabs the fridge door and pulls himself off the sticky floor.

“Where’s the Big League Chew?” he asks.

The cashier points to the next aisle. Marshall hasn’t chewed any Big League chewing gum since he was in grade school. He buys two pouches of it and takes it home. He sits at the kitchen table alone, tucking grape strands between his gums and bottom lip. He puts on a record.

The gum doesn’t taste at all like he remembers it, and Susan is never coming back home. He drags all her clothes out of their closet, wire hangers bouncing across the carpet, and dumps them on the bed with the intention of bagging them for donation. Near midnight he wakes up, sprawled across a mountain of her dresses and sweaters, his lower back throbbing. He swallows a few chalky white ibuprofens in front of the bathroom mirror and calls Susan’s sister again.

“Stop leaving messages here,” she says. “I refuse to be a part of this. I refuse to be the go-between.”

“Just put her on the phone,” he says. “Please.”

“I’m not going in there. No way.”

“Going in where? Is she with someone?”

She takes a deep breath. “Marshall, let’s not do this. Besides, it was more hers than yours anyway, wasn’t it?”

“What was more hers?” he asks — the money or the marriage? But she’s hung up. Marshall, groggy, digs for his pants under all Susan’s clothes. He grabs his fat wallet off the dresser. He’s halfway down the block when he realizes he’s forgotten his keys and locked himself out.

Funny Blooper TV News

A reporter for CNA29 News stands in front of the camera with her microphone, preparing for a live stand-up. Her bangs are like cartoon puffs of blond smoke, and she’s wearing a teal jacket with brass buttons and monstrous shoulder pads. Behind her, across the street, is a blue two-story house. All around it a maze of yellow police tape wraps through the lean pine trees.

A man was murdered in the house last night. Jealous-lover situation, one officer said earlier. At this point there is very little to report about the murder but because it occurred in a nice part of town the reporter’s producer thought they should probably cover the story anyway. Why she needs to introduce her story live in front of the house, the reporter isn’t quite sure. It feels indecent somehow.

She never used to flub her lines but lately she’s been having issues — skipping words, mixing up clauses. Once upon a time her producer called her One-Take Tammy, but she’s been so distracted recently. She shouldn’t even be here, she realizes, but at the hospital with her mother. “I’ll haunt you forever if I die in this hospital alone,” her mother said yesterday. Why would any mother say such a thing to her daughter?

When she was growing up, her mother was always bringing around different boyfriends. When Tammy was sixteen, one of the boyfriends lumbered into her room around midnight. He climbed into her bed and grabbed hold of her, and when Tammy squirmed loose and flipped on the lights, the boyfriend pretended to have been confused about which door was which. If Tammy’s mother dies, so much will have gone unsaid between them. Tammy should be the one haunting her.

Last night Tammy slept in the hideous recliner beside her mother’s hospital bed. Around two A.M. her mother turned on the television.

“What are you doing?” Tammy asked. “You need to be sleeping.”

“I would if I could,” her mother said. She flipped through the channels and stopped on a home shopping network. Tammy swiveled her chair toward the television. They watched a woman model some clip-on earrings. The woman looked a little bit like Tammy in the face, her mother pointed out, “Just around the nose. Don’t you think?” Tammy didn’t answer that. The woman on the television had an ugly little snub nose.

Tammy couldn’t get back to sleep after that. They watched prices for more clip-on earrings flash onto the screen, and then they watched a bald man with a thin mustache show off a vacuum that could suck up wet stains.

“That could come in use around here,” Tammy said, and patted the end of the bed.

“Ha. Ha. Ha,” her mother said.

When the nurse came into the room, around four A.M., her mother asked Tammy to leave the room for a minute.

“What for?”

“Because I need to ask the nurse something in private.”

“Mom, don’t be silly.”

“You can come back in a few minutes.”

“Fine,” Tammy said, “I need to get going anyway.” She grabbed her overnight bag out of the closet and left the hospital. On the drive home she stopped by a coffee shop for lattes to go. Billy was just waking up when she came into the bedroom and stepped out of her shoes and shimmied out of her underwear in front of the closet. She went into the bathroom for a shower. He followed her in to sit on the toilet lid and drink the latte she’d brought him.

“You want to talk about it?” he asked.

She said she didn’t. The steam curled over the shower curtain rod. The vanilla bar soap, from a farmers’ market, turned to goop in her hands. Billy stripped down and stepped into the shower with a hard-on.

“Not now,” she said. “Tonight maybe.”

“Just because I have an erection, doesn’t mean I’m asking for sex.”

She laughed and left him in the shower. She got to work early but then fell asleep with her head on her desk. The supervising producer came in to nudge her awake. She’d missed the morning editorial meeting. He gave her the assignment.

“But listen,” he said. “You don’t have to go. Take a few more days. Go be with your mother.”

Tammy didn’t want to take any more time off from work. She would do the story.

Standing in front of the crime scene, she collects her thoughts and waits for the cue from her cameraman. The air is muggy and her hair frizzy. Their van is parked down the street.

“Details are sparse, Gary, but it’s here that — ” As she says this, she twists, ever so slightly, to reveal more of the house, and her heel sinks deep into a bed of soft pine needles. She falls, not at all gracefully, her legs opening wide, skirt sliding up toward her waist, her black underwear and panty hose and who knows what else exposed to the camera. The microphone rolls.

The network, thankfully, cuts away to her prerecorded story.

“Are you all right?” the cameraman asks Tammy, extending a hand. He’s relatively new to the station. His name is Mike or Mel or Matt maybe. He helps her off the ground and swats away the dirt from her skirt and jacket.

“I’m fine, thank you,” she says, her face flushed red.

On the ride back to the station, he sticks out his pinkie. “I pinkie-swear that I’ll delete that footage as soon as I get back.” She hooks her pinkie in his, amused by the gesture despite the fact that thousands of viewers already saw her fall.

“Could you see my underwear?” she asks, doing her best to smile.

“Yeah,” he says. “But just a little. Not much. Nothing X-rated.”

Fatty Kids Falling Watch N Laff

A slightly pudgy boy in his white underwear slides across a blue tarp on his belly. Dish soap keeps the tarp slippery. There’s a garden hose positioned at the top, the chilly water gurgling out of it and streaming around his small body. The boy, Adam Fitzgerald, has tight curly hair, wet-dark, and he’s sliding headfirst. He didn’t bring a bathing suit to the party. Nobody told him there would be a Slip ’N Slide! Why didn’t anybody tell him? If they had, he would have brought his suit. Back home he’s got a blue one with a pocket that has another pocket inside of it. He keeps coins in there, and shells, and sharks’ teeth, and his house key.

He’s still sliding. The girls at the party in their pink and purple swimsuits, the red coolers with the white tops, the green blanket over the card table, the tall creamy brown birthday cake and the white plastic forks — everything is a colorful blur as he slides downhill. Time falls away. Space too when he squishes his eyes shut. He imagines himself like a bolt of lightning. Bodiless. An electrical current, sharp and fast. This is his third slide of the day, but it’s as glorious as the first. The sunlight warms his back. When it goes cool, he knows he has moved into the second half of his journey, the half under the shadowy cover of the oak trees. Is his heart even beating? Is he breathing?

But then his slide comes to an end. Half of his body goes over the edge of the tarp. His chest and arms land in the scratchy green grass. He stands and wipes his palms across his bare legs. Grass blades stick to his skin like a disease. He picks off each one and flicks it away with his pruned thumb and index finger.

Adam sees Madeline too late. She was next in line, and she’s sliding fast. She knocks out his legs. He falls forward and face-plants on the sudsy tarp. Madeline is pinned beneath him. She’s kicking and shoving. She’s crying. Mr. Bell comes running. Adam rolls over onto his side. Mr. Bell helps up Madeline, his hands under her soapy armpits. Adam can hear other kids laughing behind him. He runs his tongue along the bottom of his teeth. One of his front teeth is chipped, its edge so sharp it slices his tongue.

If you were watching America’s Funniest Home Videos on October 9, 1993, then you saw Adam Fitzgerald’s fall on the Slip ’N Slide at his friend’s birthday party. His video was seven seconds long and appeared in a montage of children getting mildly hurt in a variety of ways — on bicycles, on jungle gyms, with hammers, with sprinklers. His friend’s father submitted the home video, though Adam’s mother had to sign a release form before it could air. She signed the form without really thinking much about it. She assumed it would be cute. She’s always been impulsive that way, and she regrets it.

All grown up now and living in another city, her son doesn’t always answer her calls. It rings and rings, and she has to leave two and three messages before he ever calls her back. It’s not the worst arrangement. In truth she has an easier time saying I love you to a person’s answering machine than she does to the actual person.

SCARY — Elevator FAIL

Adam Fitzgerald shed his baby weight in grade school, and now he runs one of the most influential right-wing Listservs in the country. What he writes in the morning often winds up in the mouths of certain cable news anchors that evening. He keeps an office in an ancient building with ancient elevators.

The elevator doors ding open in the lobby, and a group of people rush inside together, a confluence of hot breath, bad breath, mouthwash breath, wool suits, cotton tops, warm flesh, sweaty flesh, perfumes, and colognes. One of the passengers bundles mortgage-backed securities. Another one believes the Bible should be read literally, that Jonah really did get swallowed by the whale, that there really will be four horsemen with steaming nasty breath at the end of days. A man and woman near the back, both of them married to other people, are in love with each other and sometimes sneak into the out-of-order men’s bathroom on the twenty-first floor.

Together, this group weighs 1,922 pounds. “Too many of us,” someone says, but the doors shut, and they are moving. The elevator rises arthritically up the shaft, and they are very quiet until, just before the sixteenth floor, something overhead pops. They scream, and the elevator plummets, down and down and down, all of them surely about to die, about to collapse into a dense mangled heap of body parts.

They fall for six floors before the brakes engage. They are breathing hard, their hot breath, bad breath, and mouthwash breath mingling. Somehow, miraculously, they have survived.

If you looped the video, the elevator would fall forever.

SCARY — Elevator FAIL Looped Forever

MAKES YOU THINK

Randolph is on that elevator. As it fell, he thought about… well, he can no longer remember what he thought about. Quite possibly he was thinking of nothing at all. After the elevator stops falling, the woman to his left sobs into a Kleenex. The mood is somber, but then a man behind him says, “Well, that was unexpected,” and a few people manage to laugh. But the laughter is uneasy. The elevator is frozen between floors, and they aren’t free yet. This could still go wrong.

They have to wait another twenty minutes for a group of firemen to drag them up and out by the arms. Once lifted out, Randolph checks the plaque next to the elevator. He is on the eleventh floor. The passengers mill around until everyone is entirely free and safe. The woman who was crying says someone should really complain, someone should sue the building, someone should write the mayor. Nobody responds to her. Some people press the button for another elevator. Other people go looking for the stairwell. Randolph wonders if this choice between stairs and elevator is significant. His immediate impulse is to take the stairs — but it’s not as though he’s never going to take an elevator again. What happened was a fluke, rare as being struck by lightning, and it would be foolish to spend the rest of his life climbing stairs or avoiding tall buildings altogether.

He takes the stairs.

He’s in the building to visit Adam Fitzgerald, his racquetball partner. Sometimes, between games, they discuss their work, but Randolph can never quite make sense of Adam’s job, of how a Listserv can generate an income. “So who’s paying you, exactly?” he’s asked his friend.

“You are,” he says.

“What do you mean, I am?”

“I mean, all of it, everything, what people say, the entire system. It feeds itself.”

These conversations are always elliptical and frustrating, and so mostly they just play racquetball in the gym on the second floor of this building, where they are both members.

Randolph climbs twelve flights of stairs. He’s breathing heavy when he knocks on Adam’s suite door.

“You’re way late,” Adam says.

“I had to take the stairs from the eleventh floor. Your elevator almost killed me.”

“Did it drop again? We’re supposed to be getting a new one,” Adam says, and then turns his computer slightly sideways so that Randolph can see the screen too. He clicks through his in-box. “Come and look at this. Someone sent it to me.”

They watch about two minutes of a video montage. A chubby man rides a motorbike over a dirt mound and gets tossed. A woman with a birthday cake gets knocked by a small child into a swimming pool. In front of a crowd of people at Kennedy’s Eternal Flame, an older woman trips and stumbles forward forward forward and down onto her chest. A man, Marshall, turns away from a bank ATM and slams into a wall of glass before falling back onto the floor. A small pudgy boy gets knocked down on a Slip ’N Slide.

“Look at that fat little fucker,” Adam says, and replays the Slip ’N Slide accident. He doesn’t tell Randolph that it’s him, that he’s the little fucker. The first time he clicked on this video link, he was mortified to find himself among its victims. But then he started playing it for people and forwarding it. He started posting cruel comments on the video’s thread, subjecting the fat little fucker to all sorts of online abuse. “Take it easy,” another commenter said once in response to Adam. “He’s just a poor kid.”

Adam watches his friend react to the Slip ’N Slide fall, smirking, then lets the video play forward. The falls are repetitive and hypnotic. It’s hard to believe these are the same mammals that sent one of their own to the moon. When the video ends, it suggests ten more just like it. Adam clicks on one. Beyond each video are ten more. It could go on forever, a video fractal.

“Who has the time to compile all this?” Randolph asks. “Who makes them?”

“We all do.”

“I don’t.”

“Not you specifically. But all of us, what we watch, what we want, everything, the entire system. It’s all of us.” Adam has his sleeves rolled up to his elbows. His hair is tight and curly. They’re watching reporters now. One reporter falls after getting kicked in the nuts by a giant bird. Another one, Tammy, falls backward and flashes her panties.

“God, I love local news,” Adam says. “Isn’t it the best? This morning they did a story on defective treadmills. Oh, man, you should have seen it. Funniest thing ever. The reporter actually interviewed a guy while they were both walking on treadmills.”

“You ready to play? I’ve got to be back at work in an hour.”

They leave the suite, and Adam locks the door. Downstairs at the gym, they play two games of racquetball. They are evenly matched, but Randolph wins both games today.

“Everything all right?” Adam asks. They are in the changing room, in towels after their showers, arranging themselves in the steamy mirror. “You seem a little out of it.”

Randolph combs his hair and tells his friend about the elevator, how his mind emptied out while he was falling.

“Sounds like you went Zen, brother. It means you’re an enlightened dude.”

Enlightened. Randolph tries on the word like a pair of pants that won’t ever fit right. He doesn’t know a lotus from a lama. The only time he ever meditated — “Your thoughts are balloons,” the instructor kept saying — he fell asleep and started snoring in front of the entire class.

“I never believed in heaven,” Randolph says. “Not as an actual place. But I always kind of hoped that at the moment we die, time no longer works the same and your final three seconds of brain activity might feel infinite. Like a dream that doesn’t end. And your last conscious thought would determine the dream.”

“The average male thinks about sex every eight-point-five seconds, so — ”

“But I wasn’t thinking about anything. It just would have been over. Just like that.”

That night Randolph gets home very late. Beth, now his wife, is already in bed, reading the novel about beekeepers. He brushes his teeth and then lies awake in the dark beside her. Their five-year-old daughter is asleep in the next room.

“How was your day?” she asks.

Sometimes when they sleep with their backs to each other, her voice sounds impossibly distant, like the bed is twenty feet across and they’re on either edge. He pretends, for a moment, that the bed really is twenty feet across and that he is the sort of husband who tells his wife nothing, who holds on to stupid little stories simply for the satisfaction of possessing something she knows nothing about. Pushing her away could start here, now. But he tells her about the elevator, about the nothingness, even about his fear that this life is all there is. She takes his hand and asks him for more. He tells her everything.

Funniest Treadmill & Stairs Falls Ever

Carol Spivey — whose beekeeper novel was on the Times best-seller list for forty-two weeks — runs on a treadmill in a wide and bright gym. Her speed is 6.2 miles per hour. Affixed to the treadmill is a small television screen. She has the news on but forgot her headphones, so she has to read the captions. The anchor is interviewing the defense attorney representing the cellist who murdered his wife’s lover. The case has been all over the news because the wife’s lover was a semi-famous musician. Musician‑on‑musician violence, the banner at the bottom of the screen says. The anchor asks how the cellist will plead, and the lawyer says that hasn’t been determined yet.

“We just don’t know all the facts yet,” the lawyer says.

“But I think it’s fairly open-and-shut, isn’t it?” the anchor asks. “They have a witness, the sister. They have a motive.”

“We just don’t know all the facts yet,” the lawyer says again.

Carol changes the channel. She doesn’t like to watch that kind of filth. It pollutes the mind. She runs to clear her head and think of new book ideas. But then again, the cellist’s story is an intriguing one, full of interesting contradictions. In his picture he looks like such a mild-mannered man. They say he worked in a stationery store, of all places. He was capable of producing such beautiful music, and yet he committed this horrible crime. Carol has never explicitly written about murder. She’s never inhabited a killer’s head (a type of head she has always assumed to be very different from her own). Already she is constructing a plot, an intricate one, with so many characters and story lines that she’ll hardly have to focus on the murder at all. She’ll be able to write all the way around it without touching the dark sticky thing itself.

The treadmill makes a disconcerting whipping noise, the belt kicks sideways, and it spits Carol off the back end. She rolls into a stationary bike, and its gray plastic pedal nicks her neck. She is the 342nd person injured by this type of treadmill. It leaves a small, light scar.

Later that year she joins the class-action lawsuit against the manufacturer, which coincides with the cellist’s trial. In spite of herself, Carol finds herself tuning in for the highlights every evening. They say the cellist is guilty; the cellist is not guilty; the cellist lost his mind; the cellist was depressed; the cellist was lonely; the cellist was a good man in a bad situation; the cellist was a bad man who had always acted like a good man; the cellist was jealous; the cellist had been treated poorly; the cellist had so much to be grateful for; the cellist is deeply sorry; the cellist should be put to death; the cellist should be put in a hospital; the cellist should get locked up with his cello but without a bow and rosin ha ha ha; honestly, who cares about the cellist?

Eventually Carol loses interest in the cellist like everyone else. She doesn’t write a novel about him. Instead she does what everyone wants her to do, which is write a sequel about the stupid beekeepers.

Babies Falling Down SUPERCUT

“Are you liking it?” Amy asks, and flicks the cover of the beekeeper sequel.

“Not really,” Beth says, dog-earing her page. “It’s not as good as her first book. The main character just got back together with her husband because he promised to give up his violin for her. It all feels a bit contrived.”

They are in the park down the street from Beth’s house. Beth hasn’t been snowboarding in years, but she does have a credit card now that earns her frequent-flier miles. She and her husband, Randolph, try to go on at least one adventure a year.

Her friend Amy is visiting from Georgia with her five-year-old daughter. Beth’s own daughter is only a few months older. The girls are on the seesaw: up and down, up and down. The playground equipment is shiny and new, the mulch beneath it still humid and smelly. There are rope ladders and tunnels and shaky bridges and towers and bubble-windows and slides and poles and swings. Playground isn’t the right word for this place. It’s a play-kingdom.

“They should make playgrounds for adults,” Beth says.

“I think they’re called bars.”

“No,” Beth says, “I mean it. If this place was twice as big, we would be out there playing too. Admit it.”

“Why don’t you just go ride a roller coaster?”

Beth and Amy lived on the same street as girls, and their mothers were best friends. That life can repeat itself so neatly is a fact that Beth, depending on her mood, finds either comforting or unsettling. But having her friend here for the week has illuminated certain differences between them. For instance: Amy’s suggestion that they just pick up some fast-food biscuits for the girls on their way to the library yesterday morning. Beth tried her best not to sound like a judgmental yuppie, but really — fatty lard biscuits? And later, when Beth broached the idea of dropping the girls off at a yoga class for kids, Amy looked at her like it was the funniest thing she’d ever heard: “For five-year-olds?” she asked. “Next you’re going to tell me you’re raising a little whirling dervish.”

So what if she was? Beth wanted to ask. Amy never left Georgia, and while it would be easy to blame their differences on geography or class, Beth knows those aren’t the culprits. Their lives deviated long before Beth left their home state, and besides, Amy lives near Atlanta, where there are probably a dozen kids’ yoga studios and where there are enough yuppie mothers to keep a thousand organic-only farmers’ markets in business.

When their girls are finished on the seesaw, they come running toward their mothers, elated.

Deep inside the ear is a mazelike structure of bone and pink tissue called the labyrinth, and at the end of the labyrinth is the vestibular system, which governs balance and helps us stay upright. Amy’s daughter battles constant inner ear infections and suffers from bouts of vertigo. The little girl falls forward onto her knees and palms. She doesn’t cry and she isn’t hurt or embarrassed. She stands and continues as if it never happened, though the moment is preserved, temporarily at least, on the traffic camera across the street.

After the park Beth and Amy walk their daughters to Pop-Yop, the ice cream shop, where customers don’t pay by the scoop but by the ounce. The cashier actually weighs the cup after you add the toppings. Beth can’t help thinking of livestock as they shuffle forward in line. They sit outside in the sunshine as the girls devour every drop of ice cream (Amy’s daughter actually licks the cup clean), and then Beth leads them on a slightly circuitous route back to the house, hoping to wear out the wee ones and kill the sugar rush. The strategy is semi-effective. It takes some singing and cajoling and reading, but thirty minutes later, they have the girls down for naps in Beth’s big bed.

“I can’t tell you how rare this is,” Amy says. “She hardly ever takes naps anymore. This is so nice. I feel like I should celebrate. What do you have to drink?”

“I think someone left a bottle of Prosecco here a few weeks ago. You want me to get it?”

Amy nods and so Beth pours the bubbly liquid into two wineglasses. They sit down on the couch together and appreciate the silence. Spread out across the coffee table there are a series of messy half-finished watercolor paintings. Amy picks up one. The painting is of a red street and a gray building and, behind that, a flat and tall mountain. Beth’s daughter painted it. In a closet upstairs there are at least twenty other paintings just like it.

“This is beautiful,” Amy says. “She saw it on a vacation or something?”

“No, we’ve never been anywhere like that.” Beth has a few theories about the painting, but she isn’t sure what Amy would think of them. Her friend is slumped down in the couch, feet propped up on the coffee table, the Prosecco balanced on her belly button. She looks exhausted. Beth decides to tell Amy everything — about how she occasionally finds her daughter changing all the sheets, collecting all the towels, about how her daughter sometimes insists that she isn’t a little girl but a maid in a fancy hotel, a maid with a fiancé who works on a ship and who comes to see her whenever he can.

Amy listens intently. “Huh,” she says. “And what do you make of that?”

“I don’t know. Maybe she heard it on television.”

“Or maybe it’s a past life,” Amy says.

Beth has often wondered the same thing, but hearing Amy suggest this possibility is a surprise. Amy seems to sense what Beth is thinking. She takes a long sip and smiles before adding,

“Don’t box me in. You don’t know everything about me.”

When the girls wake up from their nap, thirty minutes later, the Prosecco bottle is empty on the coffee table, and Beth is feeling drowsy and warm and wishing her old friend didn’t have to live so far away. Her daughter comes into the room wiping gunk from her eyes and snot from her nose, gazing at them confused and half awake. So much might have transpired to land her little girl in this time and in this place. Beth imagines her daughter tumbling down into her body as some kind of thin mucous light. What she imagines, really, is a kind of fall, a series of them, one life to the next, on and on, accelerating until, velocity achieved, you fell right through the universe itself and were finished. It’s an exhausting thought, not to mention a tad New Agey, not an idea she’d dare try and describe to her friend, but she wonders if there’s something in it worth holding on to for later, for after this lovely haze has left her.

“Where’s my grilled cheese?” her daughter asks, testy, and Beth’s fists sink down deep into the couch as she shoves herself upright, the Prosecco purpling her vision. Her body noodles to the left but she manages to lumber through it, crossing the living room with a short laugh, asking Amy if it was possible they’d been overserved, just in case her friend noticed the light-headed wobble.

trans/FA LL

In an art gallery that was once a shoe factory, a meager crowd wanders through the exhibits. The white walls are eight feet tall and the dark factory ceiling is at least twice that. It’s like wandering through a rat maze. Halfway through the maze there is a room with forty flatscreen televisions across two walls. On each of the screens, a person falls down but in reverse, time slowed, each body emitting a pink and purple light that moves like ripples in water.

“Looks like a music video from the 1980s,” someone says.

“Okay, so they’re falling up,” someone else says. “I guess I get it.”

The small crowd takes turns hovering in front of the artist’s statement:

Until recently I was strictly a painter. I painted women to look like swans. If you’d asked me why I did this, I couldn’t have told you. I painted what I painted. But then an old injury made it extremely painful for me to paint anymore. Years ago I broke my arm and wrist and three ribs in a biking accident. Maybe the doctors didn’t set it right or maybe I have tendonitis now. Either way, it got me thinking about the accident. My brother had filmed it and posted it online while I was in the hospital. At the time that pissed me off but then, all these years later, I couldn’t stop watching it. I didn’t look like myself at all. I could pause it right before I hit the asphalt. I looked both calm and terrified at the same time. Like I’d given in to something. Was this me stripped of all pretense and personality? Was this the actual me? Was this me confronting the void? I showed the video to my wife and asked her what she thought.

She said my face was like Moses’ in front of the burning bush — terror and awe.

I started watching other videos. There were so many of them. Millions of people had already clicked on them — and why? Scientists have discovered something called “mirror neurons.” A mirror neuron is one that will fire in your brain when you perform an action and also when you watch that same action being performed by someone else. Why we have these neurons is a mystery. Maybe they’ve helped us become more empathetic. When you see or read about someone else’s bad news, maybe a part of you is experiencing it too. It occurred to me that when we watch videos of people falling down, we are waiting for the moment of impact — for a bruise, a hurt, a collision — and that expectation makes us full participants in the event. Every fall we see is our own, and all of us are falling all the time.

I wondered if the same would hold true if I reversed the fall. Would our neurons mirror that rising? Are all of us rising right now? Are you?

— Davy V.

“I don’t think I am. I don’t feel like I’m rising.”

“So it’s about sin, right?”

“People falling. Of course it’s impossible not to think about 9/11.”

“I think it’s about how fragile we are. The loss of control. I dropped a pair of scissors once and popped an artery in my foot and almost died.”

“Is the artist here? We ought to push him down and film it.”

“He’s the one over there. In that strange white hat. Talking to that woman.”

“Pretty sure that’s his wife.”

“She looks ten years older than him. At least.”

“Supposedly she was his art teacher in high school.”

“Let’s introduce ourselves.”

Tammy is there in the art gallery wearing a black dress and dark lipstick. These days she dyes her hair blond. Not long after her mother died (no ghostly sightings yet), she left the station to start a family. Now that her sons are both in elementary school, she’s gone back to work as an editor. She steps forward to examine one of the screens more closely. She’s looking at her younger self — that teal jacket, her puffy bangs. Tammy feels uneasy. She’s not sure how this video wound up in this exhibit. She watches her body rise up from the pine straw, defying gravity: her dress slides back down her legs to meet and cover her knees, her expression transforms, eyes wide, mouth tight, arms spiraling, and then she is fully upright with her microphone in hand, twisting toward the camera ever so slightly. The video loops back to the beginning and Tammy is on the ground, sprawled, pink and purple lines rippling in the direction of the neighboring screen.

The gallery owner is in the next room talking to a group of people. He is an older man with thinning gray hair, but he is dressed in dark jeans and hip dark-rimmed glasses.

“I want to complain about one of the exhibits,” she says to him. “There’s a video of me that’s being used without my permission.”

“I see,” the man says. She leads him into the next room and points at the video, her finger only a few inches from the screen. “Oh, I see, yes,” he says, looking back and forth at Tammy in person and Tammy on-screen. For a brief moment she interprets his equivocation to mean that he intends to help her by removing the video, but then he gives her a pained look, as if what he has to say next will hurt both of them, and explains that the video, in this context, because it has been transformed — artistically, literally, and otherwise — qualifies as fair use and there’s nothing to be done about its appearance in the installation.

“But how did it even get here?” Tammy asks. “Where did it come from?”

His answer to this question is even more perplexing. These videos, he says, come from all over, from everywhere, and, in a sense, the videos belong to all of us. They are our videos, collectively ours, not a part of what’s commonly called the public domain, per se, but as a part of what could be referred to as the proto–public domain, the substrata of all recorded human experience.

“I could sue,” Tammy says without even believing it herself.

“But you’ve inspired art,” he says. “You’re the modern Mona Lisa.”

The Mona Lisa of Falling Down, she thinks. The gallery owner gives her his card. She watches the video loop through three more times before going home to her husband and doing her best to forget that things still exist even when you’re not looking at them.

Celebrities Fall Too So Funny — Beyoncé

Carmen Electra Simon Punch and More

Years have passed since Marshall was convicted for the murder of Simon Punch. There is no video of the murder itself, but there are thirty-two videos — thirty-two distinct but not wildly different angles — of Simon falling down onstage the week before it happened.

He walks onto the stage in a pair of tight jeans and a loose untucked shirt, guitar already around his neck. The woman in the front row, the one wearing the glow-in-the-dark t-shirt of Simon’s face, puckers her lips. For him? He isn’t accustomed to that sort of adoration. Until his song got used in the Julia Roberts movie about beekeepers he was never able to book venues this big.

He strums the first chord and a giant screen behind him flashes quick clips from old black-and-white movies and nature shows — frogs, bees, bears. The screen was his label’s idea. He smiles back at the woman in the front row before he sings the first verse. The lights change from purple to blue to black to purple again, swishing across the audience and the front half of the stage.

After the first few songs, a band comes out to join him. Simon walks stage left to trade guitars and slips on the spot where one of the roadies set down a bottled water during sound check. Simon’s brow hits the floor and gushes blood. He rolls over to look up at the lights. They flash red and orange. The bass player waves two fingers in front of his face. “Seventeen,” Simon says, and sits up. They bring him a towel. The audience cheers when he shows off his head wound. “If I forget all the words,” he says, “there better be a doctor in the house.” The crowd laughs. Probably he will need stitches later. The concert continues.

After the show the woman from the front row finds him backstage. Her name is Susan. She’s not wearing her wedding ring. It’s on a key chain that tinkles deep inside her purse. She left her husband, Marshall, a few days ago and emptied their bank accounts because, really, the money belonged to her. It was her grandmother that died, not his. Depositing the inheritance in their joint savings was a mistake.

When Susan begs for his signature, Simon asks for her t-shirt. “This one?” she asks. “The one I’m wearing?” She looks around uneasily but strips down to her black bra.

Simon smears his blood across the picture of his face on the shirt. “Better than a signature,” he says. She takes the bloodied shirt between her thumb and index finger. A long time ago Simon decided not to sleep with fans, but with this woman, he would make an exception. Her deep blue eyes are wide-set, her face heart-shaped. She seems kind. He can imagine waking up with her and not feeling bad about himself.

“Thanks for this.” She doesn’t seem to know what to do with the bloody shirt: put it on or continue the conversation half naked.

“Here,” he says, and grabs her a tour shirt from a box down the hall. “Sorry, I didn’t really think that through. It seemed cooler in my head. I’m on my way to this after-party around the corner. Might be fun. You should come. All the chairs at this club are apparently Fisher-Price.”

“As in, the little kids’ toys?” The baggy tour shirt swallows her whole.

“Yeah, exactly. A club decorated for kids that’s really for adults.”

“Sure,” she says, smiling. “Count me in.”

They leave the concert venue through the back door and walk down an alley wet with rain and full of dumpster-stink. Her high heels echo ahead of them. Outside the club, she digs inside her purse.

“Hold on, sorry,” she says. “My sister’s calling for like the millionth time. I have to take this real fast, okay?”

BlackBerry flat against one ear and hand cupping the other to block out the traffic noise, Susan walks ahead up the sidewalk, though he can still hear bits of the conversation. “Fine,” she says. “I’ll call him in a minute. From inside. But you do realize this will only make it worse.” She seems upset but, incongruously, turns back to smile at Simon with perfect teeth. “No, of course,” she says to her sister. “I’m not trying to make you the go-between.” She nods her head quickly. “Okay, yes, love you too. Don’t stay up.” She drops the phone in her purse and slides her arm through Simon’s. “Ready?”

Raindrops clinging to a high gutter splatter down on Simon’s neck. A taxi zooms by at the end of the block, sweeping water across the curb. Briefly, he considers running after it. He could go back to the hotel, take a hot shower, stick an ugly Band-Aid on his brow, and fall asleep in front of the television. The night could end here.

The bouncer waves them into the club, and they shove their way to a low plastic table decorated with a plastic flower in a plastic pot and an Easy-Bake Oven. The first round of drinks arrives, in little sippy cups, and then the second and third, and Simon realizes his hand has somehow found its way to Susan’s back. His hand is under her loose shirt: warm skin, the soft knobs of her spine. Later, he knows, they will wind up at his hotel — or at her house. He doesn’t care which. He downs his drink and opens his phone. She props her chin on his shoulder, asks who it is he’s calling. Sometimes he likes to leave himself voice mails — for later, like a diary.

“Hey,” he says after the beep. “It’s me. It’s you. You’re with Susan, and she says she wants to paint your naked — what was it, my naked knees?” He laughs. “God, can you hear this?” Susan grabs the phone. “You have beautiful knees,” she says, and squeezes his right knee and then passes the phone back to him. “You hear that? Things are going to get weird tonight, man. Oh, shit.” He laughs again. “Susan? Okay, Susan just fell over. I repeat, Susan just fell over. It’s these stupid chairs. She’s all right. Listen, Simon, here’s the truth: You’re smitten. That’s what I called to say. You’re smitten. God, what a word. You’re smitten with Susan and you’re, like, a thousand feet off the ground right now. You’ve never felt like this. Hey, so I’m booking you a flight, okay? For next week. You’re coming back to town. You’re taking Susan out.” She presses her face to his and shouts into the receiver, “You promised.” Her lips so close to his, he kisses her. “This is for real,” he says. “Check your email. One-way ticket. You’re smitten with Susan, and I just needed you to know it. Also, you’re sitting in the world’s tiniest chair. That is all. Good night.”