essays

Werner Herzog Is Our Witness

On ‘Grizzly Man,’ the Ecstatic Truth, and the end of a relationship

Though there’s no photographic record of the fatal encounter, no eyewitnesses, we know that on October 5, 2003 a large grizzly bear killed and ate most of Timothy Treadwell and his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard. All that was found of Tim were his spine, his right arm and hand, the watch still on his wrist. Everything else — bones, flesh, viscera — had already been eaten or scattered into the dense Alaskan brush. Amie’s partial remains were found nearby, half-covered in a pile of dirt and leaves, suggesting that the bear had gotten its fill and was saving the rest for later. Most of what we know of Tim and Amie’s deaths has been pieced together after the fact, from Treadwell’s journals, his film footage, and an audio recording of the fatal attack that speaks to the cataclysmic end of their relationship.

The would-be rescuers who arrived on the scene shot and killed a large male grizzly, which had been dubbed “Bear 141” in Treadwell’s notes — a bear he had not even bothered to name, perhaps because he knew that to name and anthropomorphize this bear would mean acknowledging that he couldn’t control or contain it. When they later cut open Bear 141, they found evidence of human remains. From the campsite they recovered a video camera, which contained a gruesome six-minute audio recording. Or perhaps the right word is “grisly.” It stays with you… At least, I imagine it would be difficult to leave behind, to get the sound of it out of your head. I can’t know this, however, because I’ve never actually heard it.

In one of the more powerful scenes in Werner Herzog’s 2005 documentary film about the attack, Grizzly Man, the director himself bears witness to this auditory horror. Herzog is presented on-screen, sitting in front of Treadwell’s long-time friend, and former girlfriend, Jewel Palovak. The camera peers over Herzog’s shoulder, revealing the thinnest profile of his face at the frame’s edge, its gaze instead focused on Jewel’s face while she herself watches Herzog, a large pair of headphones clamped over his ears, as he listens to the recording of the attack.

There is something odd about making this craft choice in a documentary film. To have the director appear in-scene is clearly not an example of cinema verité, where the camera functions as an impassive and objective fly on the wall. Instead, we get a film in which our narrator is also the director, the controlling orchestrator of what we can access, as well as a character, witnessing the things we cannot, the things we have even been kept from witnessing. The movie offers up Herzog as the surrogate for our morbid curiosity, a vessel to contain the violence and the horror. We watch Jewel watch him listening, in an intoxicating loop of subjective, mediated witness.

Herzog tells her that he can hear Treadwell yelling for Amie to run away, to get away; that he is screaming for her to run. Herzog puts his hand up to his face. We cannot see his reaction, only Jewel’s, who, like us, has also never heard the tape. In the gaps of silence we just barely approach something close to the experience, although we cannot get all the way there with only our imagination. There is no other sound during this scene in the film. When he hands the headphones back to Jewel and tells her never to listen to the tape, and not to look at the autopsy photos, he also warns that the tape will be “the white elephant in the room all your life.”

The white elephant in the room all your life. It is such an odd thing to say, though I suppose it does suggest a truth about the recording: it’s the thing you don’t talk about but that you still feel the presence of in the margins of your everyday existence. When I watch this scene and hear Herzog’s warning, part of me still wants to ask him to hand the headphones to me. I want to hold them over my ears and tell him to rewind.

What does it sound like when the line is finally crossed, at the moment when there’s no turning back? I can almost imagine Treadwell’s high-pitched voice, frantic, shrieking at Amie, saying anything he can to get her to run and hide, to go away. It’s true that you can now find online what claims to be the actual audio recording of the attack. I could easily hear it with a single click, one tap of my finger. But I don’t. Ultimately it’s not the grisly reality that interests me, but the ecstatic reality: I want the mediated truth more than the actual recording. I want to watch Jewel watch Werner Herzog listening.

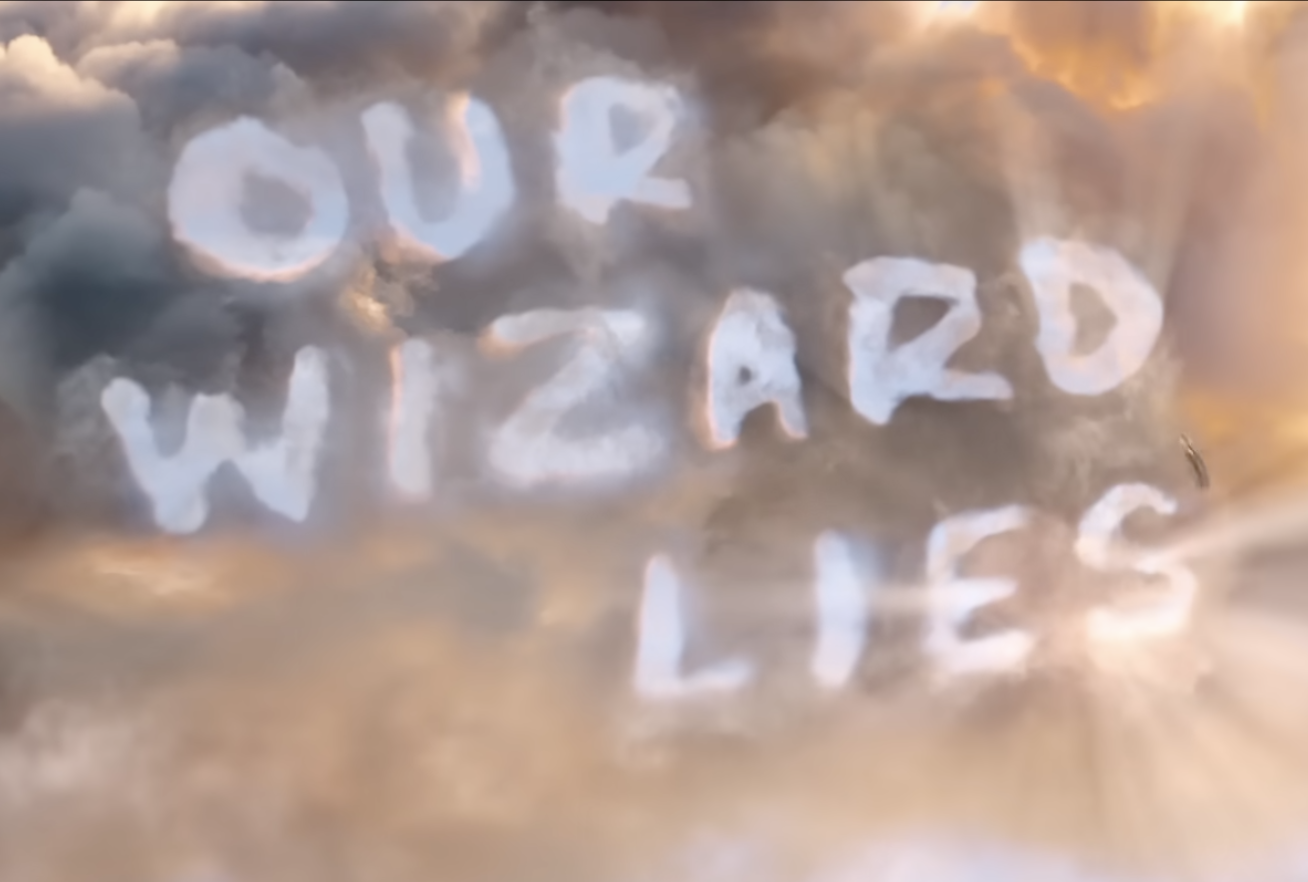

In an interview in Harper’s Magazine, as well as in a number of other interviews and lectures, Herzog has said that what he’s seeking in his documentary films is the “ecstatic truth,” a truth shaped not strictly from facts but also from fabrication and imagination. He has admitted in the past to scripting and staging certain “real” scenes in his documentary films, even to using actors instead of the actual people. But it is clearly also not pure fiction or fantasy he’s after.

In watching Grizzly Man, you would be forgiven for wondering whether the coroner, Dr. Franc Fallico, is really an actor reading lines he’s rehearsed for the purpose of playing a part. Throughout the movie, in every scene, he seems to overact, speaking with more clarity, poise, and enthusiasm than truly seems natural. At the end of one scene, set in the morgue with what appears to be a body on the table, hidden and unaddressed beneath a plastic sheet, Franc delivers his final line, before looking off-camera at Herzog, as though for approval.

The camera lingers in this moment for a beat or two longer than seems appropriate. Franc’s hands drop to his side and his posture relaxes. The resulting scene feels bizarrely amateur; it reads as messy and strange, like an editing mistake, a tail that should have ended up in a trash bin of cuts. But Herzog intentionally keeps it in, leaving us suspended in an uncomfortable space, uncertain about how much here is real and how much has been scripted, rehearsed, or even fabricated. It is an oddly seductive state of not-knowing; it is actually a kind of finely crafted and principled confusion.

This confusion leads us back to another question: Did Herzog actually listen to Treadwell’s death, or just act like he did? And does it matter? Whatever the case, Herzog thankfully did not resort to giving us a dramatic recreation of the attack, which would have been a different kind of ecstatic truth — too easy and simple, too reductive, melodramatic, and sensational. In a sense it would at once have been too fictional and too representationally “realistic,” instead of being, merely, true. Something about our filtered witness of Treadwell’s death — the strange experience of watching Jewel watch Herzog as he listens (or pretends to listen) — invites us into the experience in ways far more nuanced and complicated than a traditional documentary recreation, or a first-person, wholly factual testimony, could achieve. In making room for us to use our imagination, to speculate and to wonder, we feel our way towards what might be true.

The ecstatic truth is a truth that at once creates certainty and uncertainty, a truth that’s bigger, more wild and vibrant, more alluring and often more convincing even than a truth shaped entirely by fact or by one person’s interpretation of the facts. Stories that are apocryphal but undeniably appealing, ghost stories, tall tales, myths — perhaps all stories we tell each other again and again — depend on such ecstatic, felt truths. It is these truths that put us into a state of sublime confusion, a state out of which true knowledge of self and of the wider world emerge.

In the early Fall of 2009, my wife and I took our two kids camping in Sequoia National Park. We’d just come out of a rough patch in our lives and in our marriage and were trying to do more together as a whole family, working to stave off a divorce, our own little white elephant in the room. As it happened, the trip came during a particularly active bear season in the park, and there were signs everywhere warning about their presence. Early snows had pushed the bears down from higher elevations in search of food, desperate to pack on pounds for the coming winter. Nonetheless we remained undeterred, and I was even a little extra excited.

Our campsite was a patch of dirt beside a picnic table perched on a hillside, surrounded by other campsites with little space between us. We kept our food in a locked metal bear-proof box, and made sure that we didn’t have anything with an odor inside our tent. After setting up camp I loaded our daughter into a backpack carrier, and the four of us set out on a short hike, up a main road to an area with trails. We were hardly more than a few hundred yards away from the camp, winding through clear-cut forest on a dirt path, when we saw our first black bear. He was ahead of us, off the trail, foraging in the thicker brush but still clearly visible. And he looked big, at least three hundred pounds. We all stopped and watched him for a few seconds and it was exhilarating. I wanted to get closer, and took a few steps towards him with my daughter on my back.

“What are you doing?” my wife asked.

“I just want to see it better.”

“Um — no. Seriously. Come on, Steve, let’s go.”

Behind me, my daughter chattered and pointed at the bear. She tugged on my ears. My son meanwhile looked up at me with concern on his face.

“Really?” I implored. “You guys don’t want to see the bear.”

“We can see it from here, Daddy,” he said.

We turned around and went back to the camp. Later that evening my son and I were sitting at the picnic table as dusk settled over the campground, and we heard something in the distance, out in the half-light. It was slowly walking, crunching the twigs and leaves. It was coming towards us.

I turned on the flashlight, playing the beam down the hillside from our camp, moving it back and forth until I caught the glow of a pair of eyes, and the silhouetted form of a bear. My son and I stared and watched it come closer, its head wagging back and forth, sniffing the ground for food.

My daughter was asleep in the tent with her mother. I wasn’t sure what we should be doing. I was about to yell or throw something, make a ruckus to scare it away, but for a moment I continued to dwell in that space of awe, just before fear sets in. It was as if I were frozen there, in that brief, transient state, a state which had an undeniable attraction.

Before we really had a chance to be afraid, out of nowhere, it seemed, several men approached wearing headlamps and carrying guns. In addition to a number of large, bright lights, one of them held some kind tracking equipment. The Bear Suppression Unit — a special team of Park Rangers, trained and charged with protecting park visitors from hungry black bears — had appeared from out of the dark, armed and highly illuminated. My son and I watched as they shone their beams across the bear and blasted it with either propelled bean-bags or rubber bullets — something non-lethal, I assumed. We heard but couldn’t see as the bear crashed off into the brush, fleeing back to the dark. And, just as quickly, the rangers also departed, leaving me and my son to stare out into the waning light.

“That was crazy.”

“Yeah,” he said. “Let’s go to bed.”

As my family slept that night I lay awake, listening to the night sounds, my mind spinning and racing, as it often does. Strangely it wasn’t so much fear as curiosity and overstimulation that kept me awake, as though I’d taken a bump of some drug. It was in this heightened state that I heard the bear again, listening as it approached our campsite, the sound of its soft paws plodding on the dirt. I felt, at once, both afraid and curious. More than anything, what I wanted was to unzip the tent and to see the bear up close — to smell its musky odor, run my hands through its dusty coarse fur — but I just lay there listening, the fabric walls just separating me from the bear. The bear itself meanwhile didn’t waste any time. I heard it slam its paws into the door of the bear-box, making a loud racket, but then it quickly moved on to look for another, easier mark, leaving me alone in the ringing silence.

The next morning, as their mother slept on in her tent, I told the kids about the bear once again visiting our campsite. I recounted to them about the beast slamming into the metal box, trying to get to our food, and how, unsuccessful, it had finally left, roaming on to another campsite. Their eyes widened, and they asked to hear the story again. And again.

But somehow, between my telling them and their subsequent retelling of the tale to friends and family later on, the story subtly shifted. In their memory of the event, crafted from my narration and their imagination, filling in what I’d only heard in the dark, the story became one in which the bear not only banged against the box but also broke into it to eat up all of our food. To this day, my children are convinced this is what happened. They sometimes even conjure up corroborating images from the next day — torn chip bags, scattered crumbs, open, tattered boxes, their mother’s shock at the mess, the whole family together confronting the aftermath. They argue against me, knowing that the ecstatic truth they hold in their possession is bigger, wilder, and more vivid than the paltry facts I can offer. At some point I have to concede to them and agree: the narrative of the relentless bear that broke into our camp and consumed everything on which we’d planned to survive really is a better story. And not only that, but it also happens to be true.