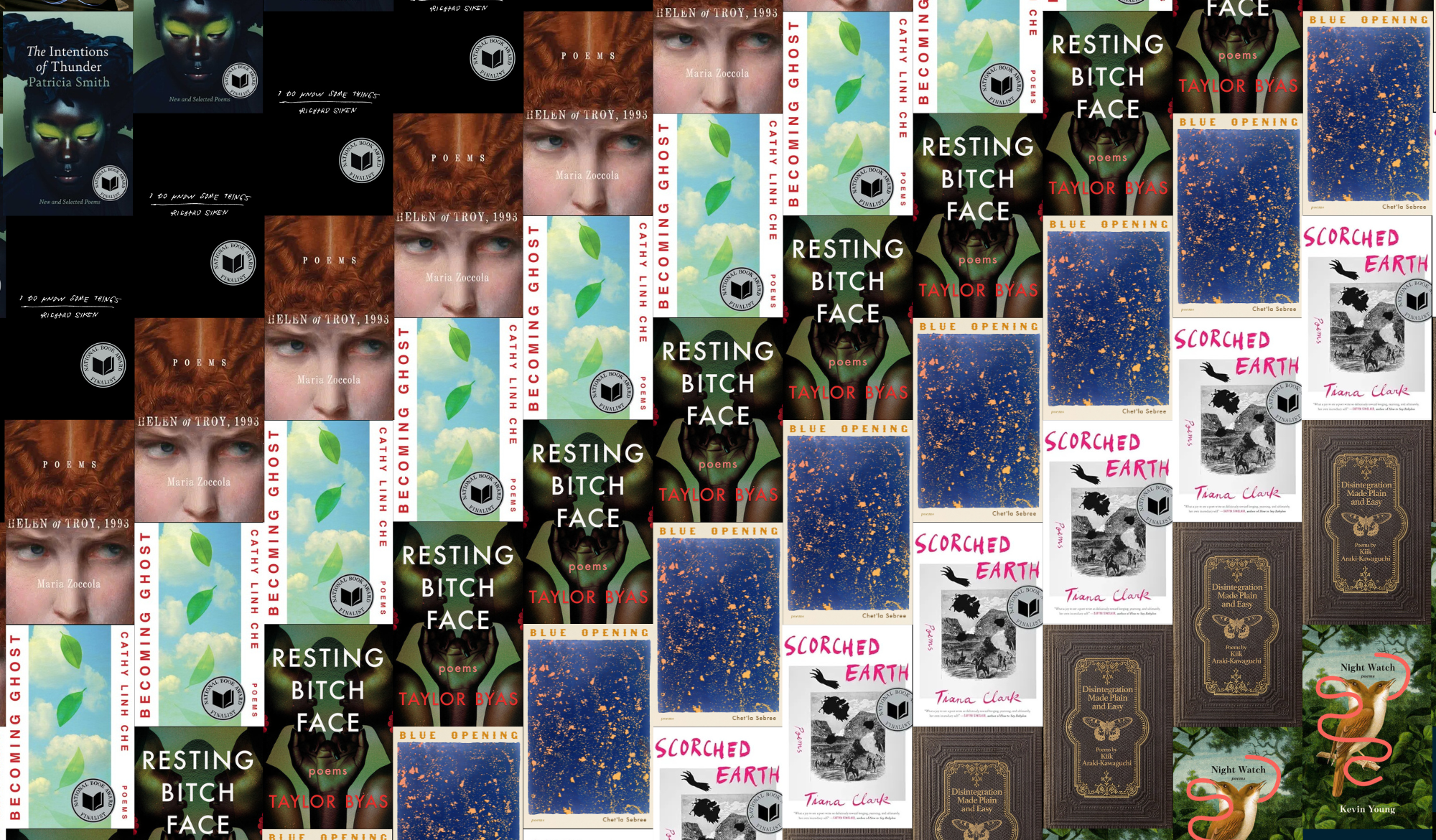

Books & Culture

What Can Poetry Do That Politics Can’t?

The questions Matthew Zapruder’s ‘Why Poetry’ fails to ask

Last year, the poet, novelist, and literary essayist Ben Lerner published a slim book called The Hatred of Poetry in which he argued that “contempt” was inseparable from poetry’s practice and consumption — and that this contempt actually revealed the “tremendous social stakes” at play in poetry, the sense of possibility that the form continued to evoke. People hated poetry because they believed in poetry. Their distaste was an expression of their sublimated desire.

Now Matthew Zapruder, a poet and one of the editors behind the Seattle-based poetry press Wave Books, has written another book-length defense of the artistic form called Why Poetry. The two authors’ arguments differ, but their premises are more or less the same: Poetry is ancillary to the lives of most Americans, at best, and widely detested at worst. “Clearly, there is something about poetry that rattles and mystifies people,” Zapruder writes in the book’s introduction. “[I want to] take seriously the objections people have, and try to address those objections clearly and simply, in order to explore what poetry is, and why, despite its supposed difficulties and obscurities, so many people still write and read it.”

Zapruder is nothing if not sincere — he seems to truly believe in the potential of poetry to improve people’s lives, and, over the course of more than two hundred pages, he lays out his case. First, what are people’s objections? Many of these will be familiar even — or perhaps especially — to those who do not read poetry. Poetry is pretentious, cryptic, elitist, and futile. One needs a master’s degree to understand it. It’s irrelevant to the larger culture. It makes nothing happen.

The two authors’ arguments differ, but their premises are more or less the same: Poetry is ancillary to the lives of most Americans, at best, and widely detested at worst.

That last criticism is a quote from a famous elegy by the poet W.H. Auden (“For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives / In the valley of its making”), and it is often used to imply that poetry is essentially apolitical; it may accomplish something on the page, it may move the individual writer or reader, but in the worldly affairs of politics, economics, society, and the state, it is basically useless. It doesn’t prevent wars, enact legislation, or inspire social movements. It doesn’t construct roads, create jobs, or sign welfare checks. In an era of intense politicization, this is an potentially damning critique. What, in the end, is poetry for?

The answer, for Zapruder, is nuanced—and it is this quality, nuance, to which Zapruder seems most attracted, even if his intention is to argue in a way that is both direct and clear. In this aim, he mostly succeeds. He is excellent at describing, in plain language, why poetry is different from other forms of writing, and how it can help people to lead deeper, more emotionally textured lives. He is less convincing on the subjects of political speech and poetry, and it is these stumbles that cast doubt on his poetic project as a whole.

Zapruder’s most arresting arguments have to do with the subject of language itself. Poetry refreshes and renews language to which we have become habituated, he asserts, drawing from the work of Russian literary theorist Viktor Shklovsky. It transforms the inherent limitations of language — the failure of words to fully represent the objects to which they have been correlated — into “a place for communion.” It combines private and public language, facilitating communication and connection. It allows for imaginative leaps and associations (Aristotle’s definition of a poet, according to Zapruder, was a person with “an eye for resemblances”). It releases us from “the pressure of the real” (Wallace Stevens’ phrase), those “mundane, terrifying, distracting, and often monetary pressures [that] can make us feel like automatons.”

It is only when Zapruder departs into the politics of poetry that his arguments become thornier and harder to accept. His first argument relates to political speech, his second to political poems themselves. For the first, he uses George Orwell’s famous essay, “Politics and the English Language,” a more recent, and perhaps more relevant, essay by Roxane Gay called “The Careless Language of Sexual Violence,” and other texts to suggest that the attention poetry gives to language is political as well as personal.

Poetry refreshes and renews language to which we have become habituated.

Tyrannical political leaders (as Orwell and another of Zapruder’s sources, the German political theorist Theodor Adorno, knew all too well) often distort language to conceal their own violence — think of the Bush Administration’s euphemistic “enhanced interrogation techniques” instead of the more honest and troubling “torture.” Imprecise language leads to imprecise thinking, according to Orwell, with devastating sociopolitical results. Zapruder laments how “a certain word or phrase will take over the language of pundits and politicians and make its ways through our screens and listening devices and then pass through us like some kind of virus. Arab Street. Republican Brand. Public Option…” Part of poetry’s power, for Zapruder, is its ability to rehabilitate this fallen language into something more beautiful and true.

Such efforts are indisputably valuable, but I fear the political import of such “defamiliarization” is less than Zapruder would lead us to believe. The avoidance of abstraction and cliché, the deployment of unusual descriptions, the turn of a disarming phrase — these are important to literature, and they can be meaningful to an individual experience of politics. But mass communication, repeating memorable words and phrases, and even the employment of propaganda are vital to electoral politics in the sense of winning elections, building coalitions, and passing legislation. Imagine trying to persuade a nations’ representatives to support public health insurance, for example, without a bland, pithy phrase like “public option” to rally around. Political speech, in this context, is antithetical to the poetic project Zapruder describes. One needs language that is familiar, not unfamiliar, that can be employed and understood by large masses of people. “I am fascinated and horrified…when I hear dead metaphors and totally familiarized phrases start to emerge from my own obedient mouth,” he writes. I relate to this horror. But does he suggest we use poems?

One needs language that is familiar, not unfamiliar, that can be employed and understood by large masses of people.

Other problems arise in his chapters about political poetry. He argues that poems that express prefabricated political points of view can devolve into “editorials, or sermons, or rants.” “When that happens,” he writes, “the poems, however laudable in their intentions, can stop feeling like poems, and become more like, at best, poetic prose, and at worse, decorative, unnecessary lyricizing.” While poets should engage with the deepest and most complex moral questions of their time, Zapruder maintains, their responsibility is to language most of all. “[F]ollowing the suggestions of the material of language, instead of trying to bend it to expressing what we already know, is inherently ethical,” he asserts, appropriating an argument from the poet Richard Hugo. Make poems beautiful and true, he says, channeling Keats, and the poet will arrive at an ethical place.

But Zapruder wants to have it both ways — to preserve poetry as a place for intellectual and creative freedom and also for the outcome of this unlimited freedom to be automatically ethical. “Following our internal sense of music leads us to revealing who we really are,” he continues. But what if “who we really are” is white supremacist or fascist or authoritarian? History is filled with examples of excellent artists who subscribed to odious systems of thought, not least of whom was Wallace Stevens, who serves as the kind of patron saint of Zapruder’s book. Stevens, it must be remembered, once wrote a poem called, “Like Decorations in a N****r Cemetery.” Beyond this more obvious example of historical villainy are the more mundane and widespread instances of contemporary white poets who write unconsciously white supremacist poems, contemporary male poets who write unconsciously male supremacist poems, contemporary capitalist poets who write unconsciously capitalist poems, and so on. To say that if a poet writes something that aligns with her own standards of truth and beauty the result will automatically be ethical is pure magical thinking. Poets are no more ethical than anyone else, nor are our inner lives any less poisoned by the political systems we inhabit.

Poets are no more ethical than anyone else, nor are our inner lives any less poisoned by the political systems we inhabit.

Politics, for Zapruder, seem primarily to be a matter of personal choice, a system of values or ethics that has been developed individually and internally. “If you are a person who really, truly cares about the environment or politics or equality in matters of race or gender or economics or anywhere else, these concerns will naturally emerge in your poems,” he writes. But this line of argument fails to take into account the ways that politics are often chosen for people, not by them — and how these imposed choices create social and political identities to which individual thought, speech, and expression are often inevitably conjoined. “Regardless of how poets feel about aesthetic matters, we all agree we are citizens,” Zapruder claims. But are we? At a time when DACA, the program protecting undocumented people who came to the United States as children from deportation, is in danger of being eliminated, it’s obvious that not everyone who writes or reads poetry in American society enjoys the legal or social protections of citizenship. Nor do they have the luxury to choose which political issues they care about most deeply.

Support Electric Lit: Become a Member!

Zapruder is most compelling when he discusses the ways poetry can engage individual imaginations to break down social boundaries and divisions. Here, too, however, there are holes. “People do not believe in inequality or racism or global warming because they have not been informed,” he says. “[T]hey disbelieve because they cannot or choose not to imagine.” It is true that imagination, as a starting place for empathy between individuals, is essential. As a politics, however, it is inadequate. Imagine for a moment, if you are not one yourself, an undocumented DACA participant currently fearing displacement from her home because a group of powerful white men made her abstract and so politically expendable. Does Zapruder mean to suggest that this person imagine the realities of the powerful people who seek to do her harm? More likely, he intends the opposite. But then who is he writing for?

The answer, I suspect, is people like him — white, upper-middle-class, highly educated, liberal. Zapruder does include a few poets of color in his book (Robert Hayden, Amiri Baraka, Victoria Chang) but remains deeply invested in the historical canon of American poetry (Stevens, Whitman, Dickinson) while failing to consider the harm that such tradition contains. He reduces politics to the site of the individual while failing to acknowledge the social and political structures to which individual experiences are often subordinate. And he argues for nuance and complexity while failing to recognize that, for more and more people in this country, these qualities are luxuries that they simply cannot afford.

He argues for nuance and complexity while failing to recognize that, for more and more people in this country, these qualities are luxuries that they simply cannot afford.

Reading both Lerner and Zapruder, one senses the real tragedy is not that “people” are reading less poetry now — poetry has always been a somewhat rarified form in this country — but that educated, professional people are reading less poetry now, to the detriment of their inner lives. Perhaps this is why Zapruder says, rather strangely, that “poets and [tax] lawyers both are deeply concerned with what lies at the limits of language, and the fearful and intensely attractive nothingness beyond.” Or why Lerner can make so much of an encounter with a dentist who, “as he knocked the little mirror against my molars, [seemed] contemptuous of the idea that genuine poetry could issue from such an opening.” If even lawyers and dentists have no interest in poetry, both authors seem to be saying, then our country is really screwed.

And perhaps this is a tragedy: Poetry is miraculous in many of the ways that Zapruder so eloquently describes. It can change individual’s lives. But let’s not pretend that “the renewal of language” or “poems as vehicles of imagination” will improve the world on a mass scale. For that, we need politics — struggle, sacrifice, slogans, and solidarity.