interviews

What Makes Florida So Florida?

Sarah Gerard went undercover and got hypnotized to understand what it means to be from the Sunshine State.

I like to joke that Florida is the one ex-boyfriend I’ll never get over. It’s been eight years since I lived in the state, but it still fascinates me. I lived the first 18 years of my life there and I still haven’t come close to figuring out what makes Florida so strange, so alluring. When I learned that Sarah Gerard was publishing an essay collection about Florida, I knew I needed to read it.

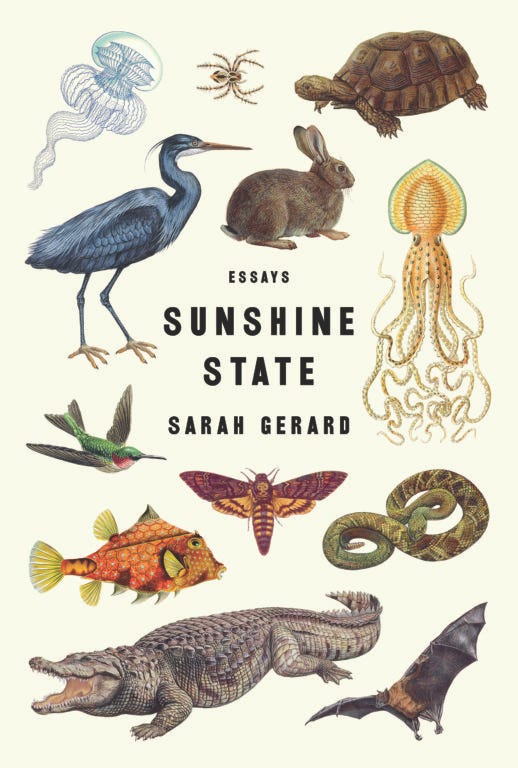

Gerard’s collection captures not what it’s like to visit Florida, but what it’s like to live there, an experience that has very little to do with theme parks or beach resorts. She writes on a myriad of topics — homelessness, residential development, teen drug culture, female friendship — and uses a new form for nearly every essay. In an essay on Amway and consumption, she blends fiction and nonfiction. In another, she uses the epistolary form to write to her childhood best friend. The book’s final essay is composed of vignettes detailing every significant animal encounter Gerard’s ever had. One of the things that makes Florida so unique is that it manages to encompass so many different identities — the sonic nightclub scene of Miami, the mega-church counties of North Florida, the old school preppiness of West Palm Beach — into one place. Like Florida itself, Sunshine State is a collage of voices and styles.

I met Gerard at her apartment, and thanked her for inviting me into her home with a six-pack of Cigar City, a Tampa brewed beer. We started the interview by sipping tea. We moved on to the Cigar City about halfway through our conversation.

Sunshine State (Harper Perennial) is a spectacular, deeply complex book. It is about so much more than just the state of Florida.

Michelle Lyn King: I heard that Sunshine State started as a book called Tracks. Is that right?

Sarah Gerard: Well, the book hadn’t been written then. That was a proposal that I was sending around. I was thinking about experiences in my life that made an impression. I’m really just describing a memoir right now. [Laughs] That’s just what a memoir is. I wanted to look at my young self as an artist, which I ultimately ended up doing, so that made its way into the new book. But then, also, I had this kind of specific trauma with a freight train, so I was planning on writing about that again. It’s funny the kinds of stories you carry with you throughout your life that you know someday you’re going to write. I’m still just…I don’t know if I’m really ready to get to that yet. Animals figured largely in the book. So, animal tracks were another kind of track.

[But] people wanted a more specific idea. Editors wanted something they could hang a marketing plan on. And actually it did help me narrow in on more specific ideas, like the bird sanctuary. Things that were specific to that place. Place has always been something I’ve had a hard time understanding. In the past, I’ve been so focused on character. In Binary Star the voice is so isolated. And, like, America is the setting. It’s not as specific as Florida. Florida gave me characters, actual characters from that specific place.

MK: One thing that immediately stood out to me about the book is that — at least in some of the essays — it’s not always a book that’s so obviously about Florida. Sometimes, sometimes it is, like in the title essay, but other times it seems that it’s the details that are very Floridian. In “BFF,” you use Florida almost as an adjective. You describe the tramp-stamp as —

SG: So Florida

MK: So Florida, yeah. What does that phrase mean to you? What makes something so Florida?

SG: I guess I’m referring to the cliche of trashiness. White trash. White poverty, bad education, drug abuse, trailer park, trailer queen. That’s what that means. But it’s troubling because along with that the word “tramp” is associated with it. We associate trashiness with female sexuality, looseness. Using sex as a means of exchange, which is what my friend in that essay winds up doing in certain ways. Using her sexuality to get by. I think [that’s] very characteristic of some people raised in Florida. It’s an experience in Florida that we’ve all at least seen.

MK: Oh, definitely. I kept reading that essay — and other ones, especially the one where you’re talking about your senior year — and picturing people from my own school. One piece I really want to talk about is the Amway essay. I want to begin by talking about the form. You blend nonfiction and fiction, which is something you don’t really see a lot. How did you come to that decision?

SG: I originally wanted to write about residential development in Florida and how it has shaped the landscape. A place where I decided I could do that was in the Bayou Club. I was really interested in how we associate economic success in this country with material possessions, and then how our lives kind of transform around us in this McMansion style. A good way to start digging into that idea of success was looking at my parents and Amway. I wanted to think about how touring those houses might have shaped my idea of success and how that might have guided my life. I wanted to peel away any delusion. I remember it so fondly, but with this cringe.

I started the essay by reaching out to a real estate agent and telling her I’m a writer and asked if she could give me a tour of one of her houses. I actually got a lot of information that I found really valuable later on, but I could tell she would’ve talked to me differently if she’d thought I was actually in the market to buy this home. So, the next two tours I went on, I brought along a friend and basically told him to act like my husband. We dressed up, which was really awkward actually. I had a hard time deciding what to wear. Looking back, I never would’ve mistaken myself for a millionaire.

MK: Oh, wow. What did you wear?

SG: It was a thrift store dress that I wore with a silver belt, and I wore some high heels, and I brought one of my grandmother’s alligator skin bags. I tried to paint my nails, but I’m really bad at painting my nails, so there’s no way this person thought I was a millionaire. Although, one of the relators wound up looking me up. I used my real name because I had to email her, and she looked me up. She was like, “Ooh, you’re a writer.” She kind of convinced herself that I was this —

MK: That you’re, like, Jonathan Franzen. Or, like, selling your books into major motion pictures.

SG: Right, exactly. Yeah, so, for the next two tours I kept the recorder hidden in my bag and I’d already made the choice to use it as fiction. I wanted to be able to disappear into the fantasy. Plus, the quality of the recording was bad, so I was able to reshape those and use them as fiction. But the descriptions of the houses are accurate. The dialogue and actual story were not.

MK: I didn’t really know much about Amway before reading the essay and it took me until you actually said Betsy DeVos’s name to realize its the same DeVos family, to realize she’s the wife of the founder. I kind of freaked out when I realized.

SG: Oh my God. Isn’t it horrifying?

MK: It’s insane.

SG: Yeah. They’re so sinister. But it speaks to the degree to which we can delude ourselves. I actually believe that they believe they are…their records are clean, you know? That’s the terrifying thing. They’re so convinced.

MK: And if there is one person they help, they believe that’s the person who speaks for everyone.

SG: Exactly. Yeah. Well. Yes and no. This is when I start to doubt. It’s clear…they have all the numbers, right? It’s clear that the people who are endorsing the company are the highest level achievers in the company and they’ve been with the company forever. It’s very, very rare that someone actually rises to the top. Only so many people can be at the top. It’s organized that way. So, it’s not like they don’t have all the information. They just…it’s almost like they can’t live with themselves or something. Or it’s greed. It must just be greed.

MK: I feel like maybe it’s greed and they’ve set up traps in their head so that they don’t exactly have to confront that fact.

SG: Yeah.

MK: One thing I want to talk about is money and class, specifically as it pertains to Florida. There is a lot of money and wealth in Florida — in places like the Bayou Club — but all of it — or a lot of it — is new money. It doesn’t have the same history and “class” as somewhere like Connecticut or Boston. Pretty much everyone I know who is wealthy in Florida is first generation wealthy, and there’s a gaudiness to the wealthy communities in Florida that I don’t see in a lot of other wealthy communities. Were greed and wealth something you were considering when writing the essay?

SG: I don’t know if that was the point of the essay, but it was something that led me in there. I think I was actually more interested in my family, how we were able to fall for it at all. Me, I was a child. But I did. Once you learn to think a certain way, you can always return to that way of thinking. I remember exactly the ways that I would talk to myself as a person who was destined to be wealthy. It felt like it was inevitable as long as my parents stayed in Amway because it was something we continuously told ourselves, and everyone around us told us that, too.

“I remember exactly the ways that I would talk to myself as a person who was destined to be wealthy. It felt like it was inevitable as long as my parents stayed in Amway…”

MK: Through the process of writing the essay you wound up learning about your family. You learned that your mom had —

SG: Had never liked it, yeah. And had been made to lie. Well, not lie, but conceal her feelings. She went along with it to support my dad because he believed in it so ardently. Yeah, so, what was I trying to get at about wealth? Looking back on it now, that way of thinking feels so empty to me. Having the values I have today, I can’t believe I could have ignored them. I don’t know if I’m saying that right. That I could have thought wealth was so important, I guess. It was a very selfish way of thinking. There’s a moment in the essay where I hurt my mom’s feelings. That disgusts me. It’s so shameful to think about that now. And that was really telling, actually. To see that these ideas would hurt my mother. It was very eye-opening.

MK: I want to talk about the research you had to do about your family — especially your mom — for this collection. Especially in “Mother-Father God,” I imagine you almost had to research your mom, in a way. What was the “research” process like with your mom in that essay?

SG: I did one long interview with her and then I called her a bunch of times after that and then emailed her. She sent me her prayer journal.

MK: How much did you know before starting the essay?

SG: Well, I remembered hearing about the Emma Curtis Hopkins College, and I knew the people who were involved in it. And I would go to church regularly. Less so as I got older, but they were people who were members of our community, so they’d come over to the house. They’d have meetings in the house. But I don’t know that I really understood…to me it felt like a big, important thing when I was a kid, and now I realize it was a small but fascinating effort by a really enthusiastic group of people. Very spiritually driven people. It’s interesting to me how the people who were involved in this were also successful in their careers. It’s kind of a hair-brained scheme, but Dell deChant was a professor of Theology at the University of South Florida. My mom had a master’s degree. These were real things, but it’s kind of a magical thinking venture. It’s interesting. It’s odd to me.

MK: Did you give the essay to your parents after you finished it?

SG: I sent the essay to both my parents. They both had thoughts about it. The way that I described my mom’s beliefs today is slightly different than she described to be on the phone or what she had described to me in the past. She said, “Oh, actually I don’t want to say that.” It was useful because it gave her a chance to be more specific or more accurate. My dad, too. I think my dad actually had some factual corrections about the timeline of the college, or who did what. It was a really interesting process. They were very open to it.

MK: How did you decide on these essays for this book? I imagine it must’ve been hard to narrow down.

SG: Well, the original proposal for Sunshine State had twelve essays. Four of them were compressed into two. And then I cut another two, I think. For instance, Linda Osmundson who appears in “Mother-Father God” was going to be her own essay. The Amway essay was going to be its own essay, separate from an essay on residential development. I’m glad you’re asking me this because now it’s all coming together. I mentioned the recordings I made earlier. Instead of trashing that essay on residential development I thought, well, we toured the Bayou Club anyway. I thought the essays would speak to each other in that way. So, then I got to use those audio recordings for fiction. We have to learn to use our tools in creative ways, or turn mistakes into opportunities. [Laughs]

MK: I want to talk more about animals. It seems like one of the main through-lines in the book, and, speaking personally, I know animals were so central to my experience of Florida.

SG: They just seemed to be omni-present as I was growing up in Florida. I think in the book they act as kind of spiritual guides. Or just…

MK: Well, you talk about what brought you to the title essay originally was —

SG: Birds.

MK: Yeah. Having this experience with a bird.

SG: Yeah. Exactly. They’re calling out to you, in a way. They’re kind of little symbols. I treat them as symbols in my life. I think I’m coming out of an elephant phase and I’m moving into an alligator phase right now. [Laughs] I said this to somebody recently. But for a long time I really identified with the elephant, and it’s nobility. Its docility, despite the fact that it’s so huge. If you look around my apartment you’ll probably see a lot of elephants here and there. They’re kind of hiding. Now I think I’m moving into an alligator phase. I’m really drawn to the alligator on the cover of Sunshine State. I’m feeling kind of fierce and misunderstood in my life, so I think the alligator is a better creature for me. But in all fairness, the alligator is a pretty docile creature, too. Unless you upset it.

So, I think I wanted to write about animals in Sunshine State because they figure so largely in my memory of growing up in Florida. Especially the alligator. When I was nine we found an alligator in the ditch of our backyard and we had to call animal control. It was a nine-foot long alligator, and my neighbor had actually warned me about it. She showed me a picture of the dog that the alligator had eaten half of. That was etched in my memory. And then a kid in my school had been chased by an alligator in the park nearby because he was throwing marshmallows at it. Just things like that. We were so close to animals growing up there. I truly feel like I have an understanding of the Animal Kingdom. I’ve always felt close to animals in my life and aware of them and aware of their emotional world.

MK: That’s a good transition to talk about the title essay. So, you had this experience with a bird, which led you to volunteer for six-weeks at The Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary in Indian Shores, Florida. The bird sanctuary turned out to have a great deal of controversy behind it. (The majority due to its owner, Ralph Heath Jr., who was accused of stealing money out of donation boxes and was illegally housing wild animals in a warehouse.) What did you know about the controversy before you started volunteering?

SG: Nothing.

MK: Nothing?

SG: Nothing until I got there.

MK: So that moment when she was like “Are you a journalist?” was just the first thing to tip you off?

SG: Yeah. I was just like, Well, now I am. [Laughs] I should have maybe done more research up front. I didn’t even think to look in the news. I remembered it being just this quiet little out of the way place. I read their website. I even read a couple of their newsletters. But I didn’t go searching.

MK: You weren’t like, “I wonder if the founder is a hoarder.” I wound up looking those pictures up. They were very upsetting.

SG: Holy shit. I’m actually glad he wouldn’t let me in. I think I would’ve vomited.

MK: Deeply, deeply disturbing. So, you set this volunteer session up, and were they just kind of like, Yeah come on down?

SG: Yeah, they didn’t mention anything. They weren’t like, NO OUTSIDERS. They told me to stop by when I came down. I went down there. They told me to come back the next day and fill out an application because the volunteer coordinator wasn’t there. I came back. I told her I was a writer and then she asked if I was a journalist. From there, I just started interviewing people. The first person I talked to was this guy Chris, the groundskeeper. I followed him around for a day. We cleaned the pelican enclosure, I think. Originally I thought maybe he would be the star of the essay because he actually has an interesting story. He was addicted to Oxycontin and was arrested for trafficking or something and had to do a bunch of community service and lost his job. I was like, okay, well, this is kind of thematically relevant. I write a lot about addiction, and certainly Oxycontin in Florida was an epidemic. So, that was motivating. But then I just started overhearing talk. And in that first conversation with Chris the warehouse came up and I was like, What’s in the warehouse and he was like, You don’t know what’s in the warehouse. [laughs]. I was like, Uh, yeah, I do. But he wouldn’t tell me. I just got nosey. I followed the story.

MK: There are people in that essay who, if it were a piece of fiction, I’d be like these people are not believable at all, but it’s nonfiction and it’s Florida, so…

SG: Yeah. [Laughs] Who is your favorite character in the essay?

MK: Jimbo. For sure.

SG: Me too.

MK: He’s incredible. The exchange where he’s like, Sometimes I imagine I’m a macho man, and you’re like, I knew better. He also really believes in Ralph’s character.

SG: He really does. Even in the end when he was crying on the phone with me he knows that Ralph didn’t intend to do harm. That’s the heartbreaking thing about it.

MK: It would have been easy for you to write Ralph as a villain, but the essay understands that it’s more complicated than that.

SG: He’s just such a nice guy. He’s just so sweet. He reminds me of a child. I don’t know. I think it has a lot to do with his relationship with his father. Needing to fulfill his dad’s expectations. It has a lot to do with privilege, too. He never had to experience the hardships that the rest of us do. He never even had to have a job.

MK: He also seems like he is not…I don’t think he understands humans very well. Perhaps because he understands animals so well.

SG: Oh, yeah. I actually think Greg and Kelly are the most suspicious ones.

MK: For sure. They reminded me of the eels in The Little Mermaid.

SG: Oh, yeah. Wow. Good one. Nice nautical comparison. Yeah, they’re funny. Actually, the conure that I adopted at the end of that essay for four days was inspired by their conure, who was very cute that day.

MK: I do really believe that Ralph’s goal was to save as many wild animals as possible. If I’d just read newspaper articles, I probably wouldn’t believe that, but the essay made me believe that.

SG: One hundred percent. He dedicated his life to it. It’s the only thing he’s ever done.

MK: As I was reading the essay, I was amazed by how many people were willing to talk to you and what they were willing to tell you.

SG: They wanted to talk to me. Every one of them. Because it’s concerning.

MK: And everyone in that essay firmly believes they haven’t done anything wrong.

SG: I know. And yet they’ve all enabled him in some way.

MK: They don’t think they have anything to hide.

SG: Fuck. I know. It’s a mind trip. Yeah. Every one of them is complicit somehow. They tried to change or improve things from the inside. Each of them works really hard and cares about animals. Nobody gets paid very much. Most of them are volunteers or they work there part-time or they’re paid for part-time work but really wind up working there full-time hours. Even when they leave the sanctuary, they go on to found other sanctuaries. It’s really what they want to be doing. And, you know, it would be crushing for Ralph if he could in any way be convinced that these animals didn’t really love him in return.

MK: Or that he had hurt them.

SG: Or that he had actually hurt them. Hurt the thing he loved the most.

MK: Yeah. The images are very disturbing.

SG: Yeah. Can you imagine being the Florida Fish and Wildlife agent who had to search that place multiple times?

MK: It reminded me of Grey Gardens, in a way. Like, pre-Jackie O clean up.

SG: Oooh, yeah. Similar concept. He’s such an island, isn’t he? He’s not there anymore. They’ve actually rebranded. His sons bought it and I believe…what is his name? One of the rehabbers. Gary, I think is his name. He’d been volunteering for a long time and is now the general manager. So, that’s the comforting. Ralph is reportedly not involved, but who’s to say?

MK: I want to talk about the essay “Records,” where you track your senior year of high school. What your research process like for that essay? Were you looking at old journals? Old pictures?

SG: I began with the character of Jerod. That one began as two different essays, too. I was going to tell the story of Mitch and Jerod as two separate essays. Jerod was looking a lot at the Florida nightlife culture at that time. But I was also interested in his criminal record. I have a lot of friends like that, who’ve been in the penal system over and over again, or they’ve disappeared from my life because they were incarcerated. So, I began with wanting to find him. I didn’t know what happened to him. The last time I saw him was in 2009. I went to look for him and I couldn’t find him on Facebook. There was no trace of him on the internet. But I’m a really good sleuth. That led me to track him down. I knew he’d been arrested a couple of times, but I didn’t know the extent of it. He’d actually been in the jail since 2013 or something. Very recently. I finally found him in Indiana.

But I kept trying to tell this story and I couldn’t. I was spiraling out into other people who were related to the story. I couldn’t find a through-line. I couldn’t draw a conclusion. I didn’t really know what it mean yet. I was telling all these individual stories and trying to tie them together and separately was trying to tell the story of Mitch, this experience of sexual assault with my boyfriend three days before I left for college. I couldn’t not be the victim in that story and I really didn’t want to be the victim, you know? That was not what I was interested in at all. When I finally began to imagine what it would be like to tell the whole story of that year it was…how do I explain this? I was finding that in telling the story of Mitch I couldn’t not tell the story of Jerod. I had to mention that I had this whole other boyfriend at the time. That’s when I was like, well, why is he appearing in this whole essay of his own? I think in some linked collections you can make connections like that. But it just didn’t click. I couldn’t see what it all meant until combined them, until I decided to talk about the entire year. I had to talk about it all.

MK: Why did you decide to tell the essay in the present tense?

SG: I think because, at that time, I didn’t have any retrospect. I wanted to be true to the experience of thinking and feeling all those things for the first time. It creates a sense of possible danger, because I don’t have any foresight.

MK: I can say that as a reader, the present tense really kept the energy up, and seemed to almost match the energy of that time in your life. So much of that time in your life seems like it was about moving from place to place. Being in cars, going to the movie theater, going to someone’s house, going to a party. Just moving, constantly.

SG: Yeah. And when you’re in ecstasy, there is only the present moment. Music is like that, too. You only hear this one beat at a time, but they’re all linked together. I wanted…what did you say a second ago? Oh. The energy. Yeah, I had a lot of energy at that time. My sexual impulses were all mixed up with my artistic impulses and the general impulsivity of being a teenager. I was trying to find myself. Trying to cobble together an identity through experimentation and different art forms and different people and modes of expression.

MK: That comes across in the essay. It’s so tricky at that age. You’re trying on all these different personalities in a way you never are again. I want to talk about the edits you made to “BFF,” the epistolary essay about your relationship with your childhood best friends. They’re minimal, but seem pretty important. What kind of work did you do in changing it from a stand-alone chapbook (with Guillotine) to an essay in a collection?

SG: Oh, wow. I’d have to look at my editorial notes from my editor. Well, in the chapbook it ends with her wedding, right?

MK: And you’re looking at her husband.

SG: Yeah. I think my editor thought it would be more fitting to end on this reflection on us. This bittersweet childhood moment of innocence. It did feel more accurate. In the chapbook I ended up moving chronologically — oddly, because I don’t do that elsewhere. It felt right to go from being 12 to her being married. I think it’s also maybe tacky to end on a picture I’d come across on the internet. It’s not a sentimental thing, you know? It’s sad, but it’s not something that’s special to us or in our relationship. It’s a moment that happened after our separation.

MK: And then it’s also ultimately more about you. It’s about you deciding what that picture means to her and what it means to you. But it’s not an essay about you. It’s an essay about both of you.

SG: Yeah. Exactly. Yeah, so in that last memory, it’s us together, poolside. [Laughs] Right? Our feet are in the pool. We had these matching bathing suits. Except hers was purple and blue and white and pink and mine was green and pink and blue and all different colors. I think yellow, too.

MK: Do you know if she read the chapbook?

SG: I don’t know. I recently learned that she’s welding. She’s in welding school. I’m happy for her. But, no, I don’t know if she’s read the chapbook. She recently liked on Instagram — this is how insidious the internet is, right? This is what I know about her. Things I happen to see on friend’s feeds. But she recently liked a picture of my friend holding my book. So, I know she knows the book exists. I don’t know about the chapbook, though. It’s okay. I still love her. She’s a beautiful person.

Patricia Engel on Florida, the Courage of Immigrants, and Writing a Novel of the Americas

MK: One of the edits you made that I took note of is you talking about are sorry that you couldn’t love her in the right way and then — you don’t say this part in the chapbook — but in the way that she deserves.

SG: Oh, yeah. Yeah. She does. She’s a beautiful person who has been through a lot. That’s what trauma does. It makes people protect themselves with their behavior.

MK: In another interview you talked about how, short of doing something out of spite, there isn’t a reason not to write about someone.

SG: And to protect their privacy.

MK: Right. Yeah.

SG: But it was never my intention to publicly embarrass her or have the last word or make her the bad guy. I would never want to do that. I just needed to resolve something in myself. It really hurt the fact that we could never….there had just been too much that came between us. There were too many things we had never said to one another and they had just piled on top of each other over the years. There was no way for us to talk about any of it without really hurting each other.

MK: You take a great deal of blame in the essay and throughout the whole collection you expose these parts of yourself that are…less than favorable. I’m thinking of that scene in the Amway essay where you tell your mom you get everything you want.

SG: [Laughs] God. So Embarassing.

MK: Whenever I read nonfiction where the author hasn’t done anything wrong, I’m immediately like, You’re lying and I do not want to read this anymore. [Laughs] But was it difficult to include those parts of yourself at all? It would’ve been easy to just…not include them.

SG: But it’s important to include. I think your writing should transform you and I think the only way to do that is by truly confronting yourself, who you are. That was really a part of who I was. I thought I was special because I was spoiled, that that was something I deserved and should be proud of. That’s a disgusting thing to have to admit, but I don’t think that’s who I am today. I mean, I laugh and say it’s embarrassing, but I don’t subscribe to that way of thinking anymore. A piece of writing should also show us how our thinking has changed over time and changes in the writing of the piece. I think that you can’t show how your thinking has transformed if you don’t include every step of it, every aspect of it. If you don’t really show the process. I think in the Amway essay I’m pretty clear about the fact that I don’t think that way anymore. I think I even say that it brings me shame to tell this story. That demonstrates how my thinking has evolved from that point.

“Your writing should transform you and I think the only way to do that is by truly confronting yourself, who you are.”

MK: Let’s talk about the last essay in the book. It’s really good and it’s really weird. I’ll admit that in my first reading, I really struggled with it. Let’s say that, up until that last essay, the most “experimental” essay in the collection is the Amway essay. But you’re told the rules of that piece. You’re given an intro that tells you basically, “this blends fiction and nonfiction.” With the last essay, you’re not really given a way to navigate it, at least not such a straightforward map. I really want to hear about your writing process with it. So, you went to see a hypnotist, right?

SG: Yeah. I wanted her to help me remember all the animals I’d ever met.

MK: Was the hypnotist in Florida?

SG: She was in Florida, yeah. She was in Saint Petersburg.

MK: How did you find her?

SG: I Googled “Saint Petersburg hypnotist.” [Laughs] I called a couple offices and asked what their rates would be and what their methods were. And then she and I ended up talking for about a half an hour. I was like, Here’s what I want to do. It’s really weird. And she was like, Ooh, well, here’s how memory works. She was like, They’re like clusters. We talked about trauma and how a trauma memory is a like a flash-bang. She was up front in saying she couldn’t help me remember every single animal I ever met ever in my life, which was my initial intent. She was like, You just didn’t record every single one, but the ones that you come away with are the ones that have some emotional significance for you. You actually formed a bond with them. And I was like, well, that’s actually more interesting. I saw her and we went on this hypnotic journey to the bottom of a lake. We actually talked for a long time about my sensory inclinations, whether I’m more visual or auditory or sensory. She needed to find a pathway into my memory. I think we decided I was visual.

MK: Were you taking notes during the session?

SG: I couldn’t because I was hypnotized.

MK: Oh, right. Obviously. So do you remember…do you not remember the actual. Sorry. I’m so fascinated by this.

SG: I do and I don’t. She told met that I was allowed to fall asleep if I needed to, that I wouldn’t actually be asleep. It got really deep. She told me that I would continue to remember more animals in the coming days. So, for the whole time I was in Florida I was carrying around a digital recorder and as I was driving I would just be dictating into my recorder. I have notes in my phone. I have notes in my notebook. And then I organized them chronologically in a spreadsheet, and I took notes on each one. I needed a visual assignation for each animal in the essay so that it wasn’t just a dog at somebody’s house or a dog doing something. I needed specific and significant details. In the spreadsheet I have columns. There’s a column for the kind of animal, where they were or where I saw them, the year, and then what they were doing. Oh, and who — if they were domesticated animals — who they belonged to. That was another column. Then I had to turn that into…I had decided in advance that I wanted to write it in reverse chronological order, so I had to find a way to show you, the reader, that it was moving in reverse chronological order. I tried to show this with my age, with my birthday. If you saw another birthday come along then you’d know a year had passed. Then my editor finally convinced me that we should have a couple of more markers. I really wanted it to be…I wanted not to have to be so overt. I wanted it to be shown in the text.

We had to decide where the moments of transition would be. There are a couple of places where you can see that the text changes shape. The shape of the text shows you that you’ve begun a new epic or moved backwards into a new era. The rhythm would also change slightly. It was a fun and interesting and frustrating and challenging piece to write.

It was actually in the original proposal. When I was talking to Cal Morgan about it, I wanted to — he’s the one who acquired the book — originally I wanted it to be any animal I’d ever met, ever, and I said, “Well, would that include animal videos I’ve watched online?” This is the craziness of research, right? Making a note of every time I watched an animal video on the internet. And I was like, Well, I can mine my internet history. It felt so overwhelming because in the raw data itself there’s no story. You have to find the significance of it through — well, in my case — through the emotional through line of my memory. These are the animals that were significant to me that I’ve met in my life, and significant for some reason.

MK: I’d like to end by asking what you’re working on now. I know you have your Hazlitt column and I heard you’re returning to fiction.

SG: Yeah, I’m writing a novel now. I can’t say anything more about that. But I’m always writing something.

MK: How does it feel to return to fiction?

SG: So fun. I’m having a great time with it. I’m teaching fiction now. I’ve learned a lot about fiction having to teach it. It’s fun to be writing it again, and it always…I think the frustrating thing about writing in a political climate like this one is that it’s very distracting. Especially with fiction I feel like I need to be kind of isolated, which was not the case when I was writing this book, although I did go away for a month at one point. I was so productive. I wrote like three essays. But writing fiction…I don’t know. I feel so affected by what’s happening. It makes me second guess what I’m writing. That’s a really good thing, but it has stopped me as a writer. Is the thing I’m saying worth saying right now? Is this an important thing to say right now? Usually when I ask myself that question the answer is yes, so thankfully there’s that. But it’s also hard to forget the outside world while writing. It’s so tempting to read the news, which gets me so off-track.

MK: What are you reading right now that isn’t the news?

SG: I talked to Lida Yukanavitch recently. I interviewed her, so I just read again The Book of Joan. Oh, I’m also reading Jess Ardnt’s book Large Animals. It’s really good. The stories are really short and the language is so crazy and playful.