Books & Culture

What We Need Right Now Is the Gentle Novel

Books like Henry James's "The Ambassadors" recognize that violence and trauma are not the only serious subjects for art

For those of us who are both responsible and fortunate enough to protect public health by staying home, the past year has raised questions about what we should be reading and watching and listening to during periods of crisis. In the early days, a lot of people I know reached for stories about disease outbreaks, like Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven or Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion. Later, those same people opted for a kind of numbing escape in Tiger King or Emily in Paris. But I have been craving a different kind of experience: in my solitude, I have wanted art that takes pleasure and sociability as its central themes, and that wants to share its pleasures and its community with me. I have wanted the kind of art that I have taken to calling “gentle.”

Gentleness is not one of our more celebrated aesthetic categories, but I want to insist upon its value, especially during historical moments like our own, with overlapping crises and ubiquitous violence. At its best, gentle art can create a fictional space of freedom from the grosser aspects of our world. And it can do so, importantly, without emptying itself out, or becoming like the “ambient TV” that Kyle Chayka recently wrote about for the New Yorker. Gentle art demands, and rewards, our attention. I am, more than anything, a reader of novels, and I was inspired to think of gentleness as an aesthetic category by one particular novel: The Ambassadors, by Henry James.

In my solitude, I have wanted art that takes pleasure and sociability as its central themes, and that wants to share its pleasures and its community with me.

When Lambert Strether—James’s protagonist—enters the scene, he is relieved to discover that his friend Waymarsh is not there to meet him. He has just sailed from the U.S. to Europe, and feels, upon apprehending his solitude, “such a consciousness of personal freedom as he hadn’t known for years.” On the ship, where passengers consorted, “he had stolen away from everyone alike,” and remained “indifferently aware of the number of persons who esteemed themselves fortunate in being, unlike himself, ‘met.’” Unburdened by Waymarsh’s presence, he will now, he decides with a purity of pleasure, give “his afternoon and evening to the immediate and the sensible.”

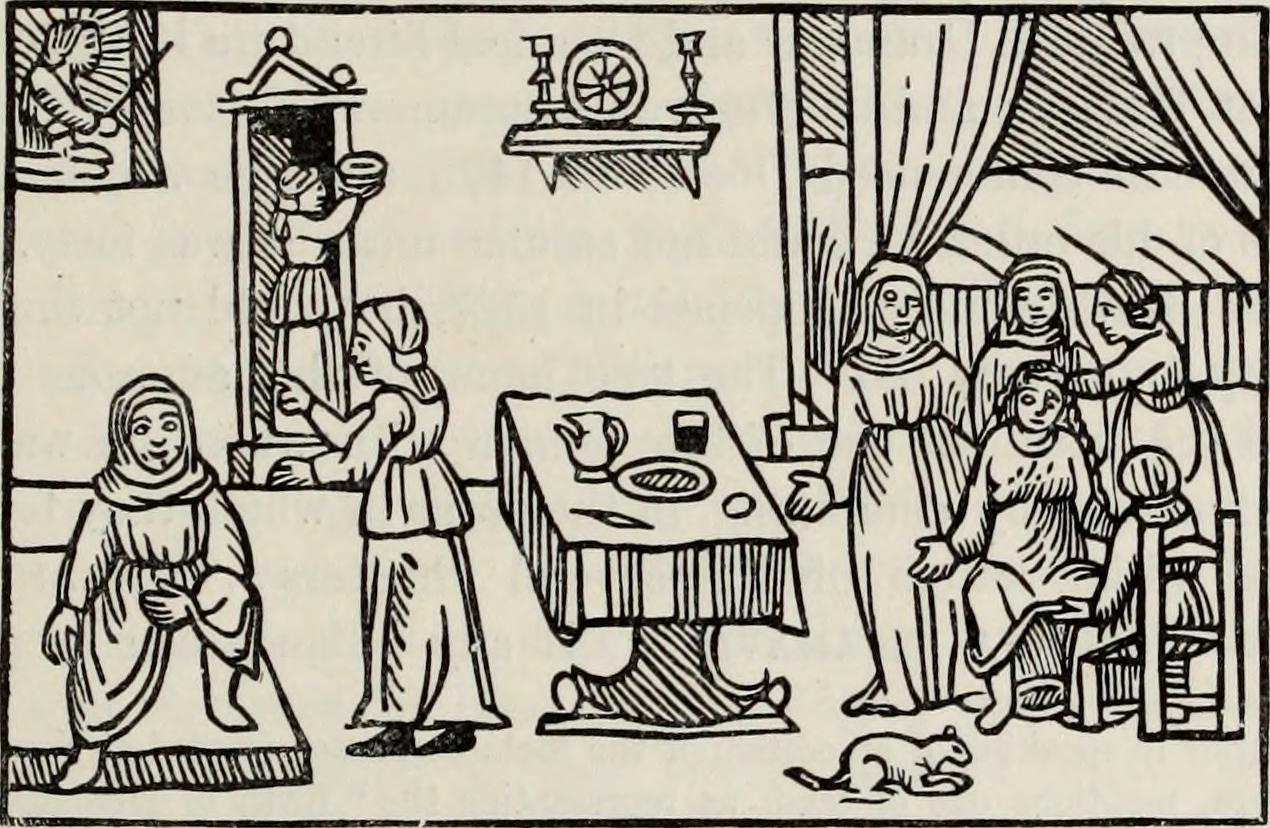

So much for the novel’s first two paragraphs. In the third, Strether recognizes, and is recognized by, another American in Europe, “a lady,” Maria Gostrey. In the fourth and fifth, he responds to her inquiry—yes, he is meeting that Waymarsh—and is surprised by his own sociability: “It wasn’t till after he had spoken that he became aware of how much there had been in him of response.” In the sixth paragraph, they have laid “the table of conversation,” and by the end of the first chapter Maria has “led him forth into the world,” toward, Strether thinks, “his introduction to things.” In this otherwise meandering novel, Strether’s shift from luxurious solitude to amiable intimacy is remarkably sudden.

The Ambassadors follows Strether as he travels from Chester, briefly to London, and then, for the bulk of the novel, to Paris. He has been sent on a mission by his fiancée, Mrs. Newsome, to bring her son Chad back to America, where the family business awaits him. The orders are clear: time is of the essence; don’t get distracted. The problem is, Strether immediately gets distracted—by Maria Gostrey first, in the third paragraph, but there will be others. In Paris, where “the cup of his impressions seemed truly to overflow,” he finds himself committed not to retrieving Chad, but to “the common unattainable art of taking things as they came.” From the moment he sets foot in Europe, he is just having the best time.

An impartial observer of our cultural landscape might conclude that violence and its effects are the most fitting subjects of “serious” literature, television, and film—that the value of art lies primarily in its willingness to confront the traumatic experiences that all-too-frequently characterize people’s actual lives. Of course, serious art should address real world traumas, but we should not make the mistake of reducing it to trauma, or to a particular politics of trauma. In part, this is because art about trauma can itself be traumatizing or gratuitous. It is also because, in a violent world, it can be difficult to see, as I think James saw, that the absence of violence—the basic fact of co-presence—is no simple matter, and is matter enough for art.

In a violent world, it can be difficult to see that the absence of violence is matter enough for art.

It seems fairly clear what gentle art is not: it is not violent or traumatic. But what motivates it, instead? The Ambassadors is, I think, James’s gentlest novel, and it gives us a chance to sketch out some of the criteria of this aesthetic category. Strether is “in tune” with Europe: he “floats,” he lingers, he enjoys “slow reiterated rambles,” he works, against a sense of guilt, to appreciate “the full sweetness of the taste of leisure”; he goes to the theater and the museum; he breakfasts at noon. To a high, if not absolute degree, gentle art is about pleasure. This is, in some ways, its most straightforward criterion. But it is not entirely so: for Strether, as we have seen, living for the moment is an “art” both “common” and “unattainable.” You might say he’s having a midlife crisis: his youth, he reflects, was not spent to advantage. “One has the illusion of freedom,” he exclaims to the much younger Little Bilham, “therefore don’t be, like me, without the memory of that illusion.” The pleasure Strether advocates is no simple hedonism: it is an existential effort, Sisyphean.

The second criterion for gentle art is that it finds its drama—its tensions as well as its pleasures—in what Simone Weil calls the “indefinable influence that the presence of another human being has on us.” Strether, James writes, “had wanted to put himself in relation, and he would be hanged if he were not in relation.” With whom or what is not named. With Chad? Yes, but also no, because as the next sentence specifies, he is never more “in relation” than when he stands alone outside a Parisian theater. “In relation” with Paris, I think—or Europe, and with everyone in it. After he is taken in hand by Maria Gostrey, Strether, “pleasantly passive,” never stops entering into relation with, well, everything.

One of the inspirations for The Ambassadors is the simple but amazing fact that people can exist in relation with each other at all. The philosopher and critic Stanley Cavell calls language—language itself, alone—“a thin net over an abyss,” but one strong enough to hold things together. That is what inspires his philosophy: that we are able to avoid the abyss of solipsism. I think there is something similar in James—a sense of wonder at the fact that people can share meaning, that they can not only coexist but affiliate. James is a master of conversations where a shared sense of meaningfulness is like an ethereal substance, one that is somehow connected but not entirely reducible to the words spoken, floating between and around the speakers. Often, meaning is shared wordlessly: a silent glance with Waymarsh “was one of those instants that sometimes settle more matters than the outbursts dear to the historic muse.” Their eyes meet, and somehow, that “indefinable influence” makes itself felt.

But relation is a dangerous game to play, as Strether discovers. Gradually, he shifts from trying to get Chad home for Mrs. Newsome to protecting Chad from Mrs. Newsome. He fails utterly, intentionally, as an ambassador. He is taken in by Chad and his circle, including Little Bilham and the glamorous Madame de Vionnet—with whom Chad is having an affair, although Strether allows himself to be convinced that they are not. When he realizes his mistake, late in the novel, “he kept making of it that there had been simply a lie in the charming affair—a lie on which one could now, detached and deliberate, perfectly put one’s finger.” At the point of Strether’s revelation, readers will likely have already inferred that Chad and Madame de Vionnet have been sexually entangled all along. Our revelation, as readers, is that Strether didn’t get it. The many vectors along which the “indefinable influence” of co-presence, the “thin net” of meaning, travel include misunderstanding and bad faith.

Gentle art can create a space of freedom from the violence of the world, without thereby becoming unserious.

The third criterion of gentle art is that it develops a style that acknowledges and reproduces the drama of putting oneself “in relation”—the sense, captured in Strether’s failure to understand, that successful communication and affiliation are challenging, even stunning, accomplishments. James’s late style is famously and idiosyncratically complex. Part of the pleasure of reading it is in solving the sentences, so to speak. As the critic Ian Watt puts it—in an essay tellingly titled “The First Paragraph of The Ambassadors: An Explication”—there is often “a delayed specification of referents.” Where we are and who we’re with and what we’re doing can be slow in their revelation, a characteristic of Jamesian prose made more demanding by his use of intransitive verbal phrases (in relation with whom?) and a healthy dose of syntactical subordination. One of the things that having a style means—or, as James puts it in his memoir, what it means to “cross that bridge over to Style”—is that one could pick a sentence almost at random to illustrate it: “But it was in spite of this definite to him that Chad had had a way that was wonderful: a fact carrying with it an implication that, as one might imagine it, he knew, he had learned, how.” Here, we see the abundance of pronouns and flurry of commas that makes his prose dense; and we also see the ways in which it is light in the triple, downhill rhyme “Chad had had.” This is what I mean when I say it demands and rewards our attention: we have to work to enter into relation with the text.

By meeting these three criteria, gentle art can create a space of freedom from the violence of the world, without thereby becoming unserious. Strether in Paris is an altogether different proposition than Emily in Paris. You needn’t rush out to get a copy of The Ambassadors to get gentle (though I doubt you’d regret it): I’ve found a similar aesthetic in more recent works like Autumn de Wilde’s Emma. and the novels of Ali Smith, and I’m sure it’s visible in many other works. Such stories offer, perhaps, only an “illusion of freedom”—and it is important to acknowledge that this particular illusion is constrained by the fact that everyone in The Ambassadors is white, and most of them don’t have to work for a living. But these are not necessary conditions of gentleness. What makes gentle art gentle is that it finds the story of co-presence and affiliation in the posited absence of violence. As crises accumulate, don’t go easy on me, but please, be gentle.