essays

When Black Characters Wear White Masks

Whiteface in literature isn’t a disavowal of Blackness, but a commentary on privilege

My introduction to whiteface was the Eddie Murphy “White Like Me” skit on Saturday Night Live from the 1980s. Blackface originated from minstrel shows — cruelly mocking entertainment made by and for white people that has portrayed Black people as inept, servile buffoons. It continues to uphold that image today. Murphy’s skit opted to show another side. His whiteface character was himself made up as a pale milquetoast, devoid of any defining characteristics, armed with a monotone voice, “tight butt walk,” and blank expression.

Murphy’s impersonation is also a satirical commentary: in the sketch, merely appearing white is immediately lucrative. In his bespectacled Caucasian persona Murphy receives everything pro bono, from a free newspaper to $50,000 dollars in cash at a bank, producing no collateral or ID. The white bank manager dismisses a Black employee who originally and rightfully denies Murphy’s loan. He then hands over actual stacks of cash to a fellow Caucasian (he thinks). Through the joined laughter of two “white” men in the safety of a “white” space, Murphy mocks that “silly Negro” banker before asking, “Are there any other banks like this around here?” At the end of the skit Murphy appears solemn when he states it was disappointing to see and experience this reality. But, he added, we have a lot of make-up … and a lot of friends. (Pan out to other Black folks being prepped to look white as well.)

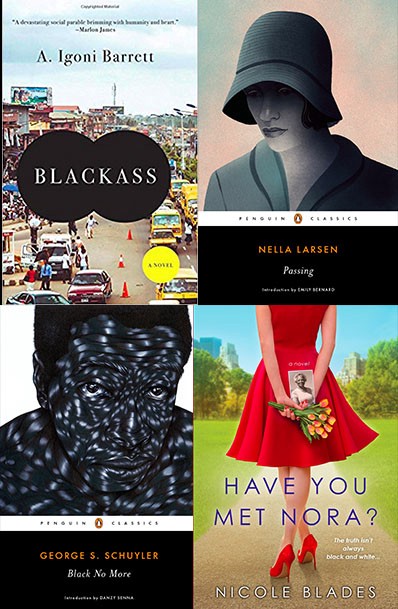

Whiteface, or Black characters posing as white, speaks to the racial dynamics between whiteness and Blackness, sometimes humorously, often hauntingly. The pursuit, or at least the semblance, of whiteness is a repeated theme in literature. In some tellings, characters actively pursue whiteness; in George Schuyler’s Black No More the main character’s body is completely remade. In others, characters allow or encourage others to see them as white for a seemingly more comfortable life — for instance, Nella Larsen’s well-known and oft referenced Passing, Alex Haley’s fictional account of his ancestry Queen, Nicole Blades’ Have You Met Nora?, and in the slave narrative of Ellen and William Craft (Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom). There’s also the inadvertent metamorphosis, like the Kafka-style one that occurs in A. Igoni Barrett’s novel Blackass.

The “hero’s” journey in these narratives relies on the current/ongoing knowledge and memory of what it means to be Black. In truth, these characters are never truly white, even as they drop anything and everything Black within their lives, be it family and friends, diction, culture, etcetera. To blend into white society as white is a covert operation. The awareness of their true Black self allows race to be a permeating factor. To pass or transform through whiteface is not as simple as a performance, nor is it caricature. Blackface aims to mock and, at its heart, demean; meanwhile, the leap to whiteness, whether enthusiastic or strategic, leaves characters in constant danger. In literature, whiteface is an analysis of how this choice becomes a way of life—and how, once the leap is made, this new life doesn’t necessarily leave characters content.

The leap to whiteness, whether enthusiastic or strategic, leaves characters in constant danger.

Whiteness was not coveted in my household, one that was filled with brown-skin people of all hues. My family enjoys everything about Blackness, from my elders’ obsession with Motown, to the uproarious Southern Baptist church services, to the inside jokes, to the plates heaped with food equating to love. But we still understood why whiteness, the perceived ease of it, could be tantalizing. It would be a lie to say that my grandmother who was terrorized by the Ku Klux Klan as a child, or my mother and her siblings who heard the deaths of many Civil Rights leaders relayed over radio and TV in real-time, didn’t comprehend the power and benefit of whiteness. The appeal of whiteface in literature, as fantasy and as satire, doesn’t always mean that a character repudiates Blackness, but that they understand the profound effects of privilege.

In whiteface literature, the reasoning for opting into whiteness as a Black person may stem from self-hate, but the impetus is rarely that simple. Whiteface stories interrogate the mentality that it’s better to be white while examining how societal gains as well as societal “norms” inflict this way of thinking on Black people. Being white isn’t better, but, for some of these characters, it seems a hell of a lot easier, or at least preferable to dealing with racism.

In the case of Passing, both protagonist Irene Redfield and Clare Kendry, Irene’s long-lost schoolmate, are Black women who have presented themselves as white for different reasons. For Clare it becomes a way of life. In the beginning, readers witness Irene indulge in the opportunity to “pass” when she goes to a fancy tea spot called the Drayton and worries when another “white” woman — -she’s unaware this is Clare — seems to stare at her as if she recognizes who she truly is. “It wasn’t that she was ashamed of being a Negro, or even of having it declared,” Larsen writes of Irene. “It was the idea of being ejected from any place, even in the polite and tactful way in which the Drayton would probably do it, that disturbed her.”

Being white isn’t better, but, for some of these characters, it seems a hell of a lot easier.

Though she chooses to live her life openly, mostly, as a Black woman, Irene understands what it’s like to pass and the benefits that come with the assumption of whiteness. While passing is not the same as cosmetically putting on whiteface, there is a connection: both cases focus on people being perceived as white.

When Irene visits Clare and a mutual friend Gertrude later on, it becomes a hen party of passing Black women. While Irene insists she’d never thought to pass, she does not refer to that conspiratorial moment shared with Clare during their reunion at the Drayton: two Black women on a rooftop enjoying the luxuries of whiteness thanks to perception. Of the three women, Irene is the only one with clearly Black lineage in her life choices, with a doctor husband who “cannot pass” and a dark-skinned son. Both Gertrude and Clare are vocally relieved that their children came into the world light-skinned, adopting the ability to pass as well. Where Gertrude’s husband has always been aware of her lineage and doesn’t care, Clare’s white husband — who has no idea that she or her friends are Black — treats the trio to a barrage of hate along with the n-word on heavy rotation. Passing (or whiteface) doesn’t protect characters from racism; it simply means the white-appearing character endures it silently, for fear they’ll be found out.

The anxiety of being “found out” permeates every work about whiteface. “I know I’m a darky and I’m always on the alert,” says the newly white Matthew Fisher, formerly Black Max Disher, in Black No More. In this tale, the opportunity to become white (with “Nordic features,” as is steadily referenced) becomes the new wave, bankrupting salons that straightened hair and those who profited off bleaching creams. It’s 1933, and for the price of $50 Black people can become white. This isn’t cosmetic; it’s a complete conversion. The Black nation jumps on this but for a few, ultimately alienating their roots while embedding themselves within white society — to the vast dismay and supreme agitation of white people. Witch hunts arise. A white person’s character is dismissed easily and readily with the whisper they may originally be Black. Everyone is suspicious and no one is safe, but Matthew, formerly Max, and his friend Bunny partner up to profit. White people succumb to their prejudices, which they turn on each other now that there are so few Black people to hate. It’s an ironic allegory for the times we’re in.

The charade of whiteface as a lifestyle takes work. In Blades’ Have You Met Nora?, the anxiety of being discovered racks the titular character into an alcoholic frenzy. In Passing, Clare seems to hold her own, yet when Irene and Gertrude meet her boorish and racist husband she slips slightly in present company. Always on the lookout, highly keen to distance oneself from their history: these are the losses that come with redefining self, and specifically with redefining self as white. For characters like Nora, who suffered sexual abuse, or Clare, who lost loved ones, it seems a small price to pay for a perceived and profitable future. Even Clare mentions it wasn’t hard to maintain her charade since the aunts who raised her were white, and this was as far as her husband got to know about her. From here the paranoia remains of consequence which inevitably causes suffering. For a character like Nora, her trauma rests on the periphery, and she is eager to erase it altogether, believing that every step, faulty as it may be, will protect her as long as she gets through each hurdle of further denouncing and erasing her Blackness.

Barrett’s Blackass thrusts the titular character of Furo Wariboko into a white body with one caveat: a literal Black ass. His conversion to white was not something he asked for, and it comes on the worst day, or perhaps the best: he awakens in a white body in time for a job interview. Eventually, Furo Wariboko becomes Frank Whyte. The core difference between Blackass and others mentioned is that Barrett’s takes place in Nigeria, not the United States. So a white Nigerian is, as the narrator puts it, the outcast in certain ways: “Lone white face in a sea of black, Furo learned fast. To walk with his shoulders up and his steps steady. To keep his gaze lowered and his face blank. To ignore the fixed stares, the pointed whispers, the blatant curiosity. And he learnt how it felt to be seen as a freak: exposed to wonder, invisible to comprehension.”

Furo’s obsession with the advantageousness of whiteness (high paying job, pretty girlfriend, personal driver, perpetual benefit of the doubt) is something he also seeks to protect. He attempts bleaching creams on his buttocks (to poor results), and forsakes all who may get close to him to maintain this image and the seeming wealth that comes with it. To be white, Furo finds, is to benefit from a system he did not create, so what’s the harm in going with the flow?

What’s also intriguing in the whiteface of these novels in particular is how that knowledge of Blackness, the memory of it, is what aids the characters in a new kind of survival. What does it mean to be Black in a white-dominant society? Okay, now what does it mean to pose as white when all we’ve known is our Blackness and our limitedness within this society? That advantage is what characters like Matthew (formerly Max) in Black No More and Frank (formerly Furo) in Blackass have to their benefit. They know, quite literally, how to speak the language of their surroundings. For Matthew it’s utilizing white fear for monetary gain and status. For Furo it’s recognizing the goings-on of his hometown as well as being able to speak the language; he has the knowledge of a native of Nigeria, paired with the access of a white man.

Whiteface, or passing or posing, in literature doesn’t necessarily equate to or end on a note of Black Pride with a fist in the air (or the Wakandan crossed arms that symbolize the unity of Blackness). Nor does it mean concretely that Blackness is a burden one should readily eliminate from their lives as soon as they have the chance. Within text some of us are allowed to be in on the larger “joke,” sort of like when I first watched “White Like Me.” Even as a child I understood what we were laughing at. Murphy as white pointed to what people, Black and white, feared: of how divided things are and continue to be, of how the nature of white supremacy is embedded in everything, of how transparent this becomes when one puts the white mask on.