Lit Mags

White Dialogues

by Bennett Sims, recommended by Electric Literature

AN INTRODUCTION BY Halimah Marcus

In the acknowledgments of “White Dialogues,” Bennett Sims writes that he “borrows liberally” from a few important thinkers, among them André Bazin. Before I ever read Bazin’s What is Cinema? (in college, where else), I was seduced by the audacity of this question. What do you mean, what is cinema? Cinema is motion pictures. Cinema is the movies. But then his first chapter opens with a bold idea: like a family photo album that preserves images of the dead, cinema preserves their vitalities, “mummifying change.”

Or, as Bennett Sims puts it, “Every movie is a pyramid, stuffed tight with mummies. Every movie is a mobile gallery of death masks.” You read that and, suddenly, cinema is not just the movies.

Bennett’s version of Bazin’s What is Cinema? is, What is story? What is this thing that has been, so many times, in front of your face? The answer, it would seem, is as far-reaching and complex as you’re willing to allow.

“White Dialogues,” a story that reads like film criticism or film criticism that reads like a story, is more than influenced by great ideas. It lives inside them — plays them out, gifts them the arc of discovery and application.

For its pedigree, for its language, for its length, “White Dialogues” will make people nervous. It makes me a little nervous. Because the minute you fall in love with this story, as I did, everything becomes fair game in fiction, available for the taking like it never was before. Take Hitchcock’s best film, put it in your story. Take Bazin’s best idea, put it in your story. Borrow from Roland Barthes, while you’re at it. There are no rules. This is fiction. This is story.

Halimah Marcus

Co-Editor, Electric Literature

White Dialogues

Bennett Sims

Share article

LISTEN TO HER, BEREYTER SAYS, as together we watch the mute woman mouthing something on the screen. Earlier this semester, the fall of what is to be my final year at the University, Bereyter accepted our cinema department’s prestigious postdoctoral fellowship, to continue his so-called groundbreaking work on white dialogues. Now, several months later, on a dismal morning in November, he is delivering a lecture on the progress of his research, addressing a scattered audience of roughly twenty people — humanities majors, graduate students, film colleagues — from a walnut lectern at the front of the darkened seminar room, down here in the basement of our historic Wolfsegg Hall. Bereyter, only in his late twenties, is a natty dresser, and for the occasion he is wearing a bone-white oxford button-down with a black cable-knit cardigan, a prep-school ensemble that — combined with the short trim of his hair, his boxy eyeglass frames, and his lean build — only serves to reinforce his precocity. That is the brazen boy-genius image he means to project: so young, and yet already he has (in his own terms) fashioned a brand-new technique of close reading, or else has (as my colleagues in the film department have put it) blown cinema scholarship wide open. I am sitting alone in the back row, in one of the room’s hideously uncomfortable desk chairs, with their stiff polyethylene seats and retractable writing surfaces. Of all the audience members, I am the only one with a lowered desktop. I have laid an opened notebook and two pens atop it, even though note-taking will be impossible. The single light source in the room is the overhead projector, a rectangular turret mounted directly above my head, where it is beaming its dazzling adit through the air: a passageway of light extends between the screen and the bulb, the movie and the room. Hundreds of dust motes can be seen fizzing around inside, sucked by some breeze toward the back row. As they approach the projector’s bulb they burn whiter, rising through the light like bubbles up a champagne neck: carbonated, candent. If I were sitting nearer to the screen, I think, I might be able to see better. That is no doubt why my colleagues have chosen the front row: there, Dzieza, Plunkett, and Guss are free to grovel at Bereyter’s feet, taking notes by the glow of the white pull-down canvas behind him. Whereas I, shrouded in secrecy and darkness at the back of the room (there are three rows separating me from the nearest person: Bereyter likely does not even realize that I am back here; Dzieza, Plunkett, and Guss likely have no idea that I am back here, listening to everything), cannot see my notebook page beneath me. Until he turns the lights back on, it will be impossible to jot down my observations, criticisms, or aporia, in preparation for the Q&A. I will have to hold them all in my head until the Q&A. That is the only reason I have come to Bereyter’s talk today: to destroy him, to disturb and destroy him, by posing unanswerable questions and merciless provocations throughout his Q&A. Earlier this morning, before he turned off the lights, I was able to copy down the few scant lecture notes that he had written on the whiteboard. The first item was a works-cited entry for Vertigo, the movie under discussion: Alfred Hitchcock, 1958, Paramount Pictures. The second was a quotation, attributed to (what I took to be) an early lip-reading manual, The Listening Eye, by Dorothy Clegg: When you are deaf, Clegg writes, Bereyter wrote (and I transcribed), you live inside a well-corked glass bottle. You see the entrancing outside world, but it does not reach you. After learning to lip read, you are still inside the bottle, but the cork has come out and the outside world slowly but surely comes in to you. The last was an aphorism of Michel Chion’s: The silent film may be called the deaf film, Chion writes, Bereyter wrote (and I transcribed), because these films gave the moviegoer a deaf person’s viewpoint on the action depicted. Listen to her, Bereyter repeats now from the lectern, his body half-turned to the white pull-down canvas behind him, one hand elegantly indicating the image onscreen. He is exhorting us to listen to the woman seated at the bar. The clip in question keeps repeating itself on a loop, the same four seconds over and over. We have now had the opportunity to witness this woman mouthing her line several dozen times. While James Stewart, seated in the foreground, peers hauntedly off-camera — hoping for a glimpse of Kim Novak — the barfly in the background mutters something to her companion, smiling demurely into her drink, teasing him (or herself?) with a coquettish roll of the eyes. She is a gray-haired woman in a dark blue suit and a matching navy beret. Whatever she is saying, her dialogue remains inaudible. Her goblet is empty, perhaps she is assenting to a refill. The fact is she is not a significant character in this film. Indeed, she is not a character at all, merely an extra, with no speaking role. Though her lips move, all that can be heard on the audio track is a general murmur, the bustle of the other patrons in the bar, the clinking of drinks. Hitchcock planted her in this scene, on that barstool, and no doubt directed her to speak — to mime speech, to suggest a scenery of speech — but without positioning any microphone to preserve her voice. He must have told her, Say anything, anything at all, it doesn’t matter, just so long as we get your mouth moving, and whatever this woman chose to say that day — there on set, in Ernie’s Restaurant, in San Francisco in 1958 — it is now swallowed up in the ambient chatter of the scene. It has no bearing on the narrative. It is a pale utterance, a white dialogue. That is Bereyter’s point, when he exhorts us to listen. No matter how hard we listen, nothing will be heard. Earlier this morning, in a methodological preface at the beginning of his lecture, Bereyter explained the entire process to us. First he searches for extras, he said, scouring a film’s backgrounds, crowd sequences, and establishing shots for any signs of speech, any men or women whose mouths are moving. Next he isolates this footage and sends the clip to his collaborator, a lip-reading German professor at his alma mater, who analyzes the designated extras as best she can, and returns her results to Bereyter in the form of a transcript. These transcripts (a sample is currently circulating the room, it has not yet reached the back row) are apparently formatted like screenplays: Man 1: Cold on set. Man 2: Sweater? In this way, Bereyter said, he excavates a parallel script, an underscript, hidden between the lines of Hitchcock’s original: it is as though all this dialogue has secretly been printed there in invisible ink, and the lip reading is like a lemon he is squeezing over it. Or better, he said, as if this dialogue were a message in a bottle. That is how he came to explicate the Clegg epigraph on the whiteboard: it is as though these extras, he said, have stuffed their messages into the bottles of various backgrounds, and it is only by reading their lips that we can uncork them. Since the lights were still on at that point, I was able to jot down the word bottle in my notebook. Only five minutes into the presentation, and already I had caught him in his first mistake. For although the movie can be said to form a kind of ontological bottle, encapsulating its characters, it is the deaf person (in Clegg’s epigraph) who is bottled: by reading the extras’ lips, it is not so much — or not only — that we rescue messages from their bottle; but rather, we invite them (slowly but surely, in Clegg’s phrase) to enter the bottle that we ourselves (the deaf moviegoers, in Chion’s phrase) are trapped inside. If the background bottle is nestled inside the Vertigo bottle, then both are wedged within the Wolfsegg bottle, I thought to myself, sitting silently in my desk chair, alone at the back of the room. It is a mise en abyme of bottles, I thought, circling the word bottle in my notepad. Not long after this, Bereyter dimmed the lights. He began his lecture by bragging about his felicitous invention of white dialogues. It may come as a surprise to some of you, he said, but I discovered them quite by accident. Late one night, while rewatching Vertigo for my dissertation, I spotted an extra I had never noticed before. The scene (which he proceeded to screen for us) occurs twenty minutes into the film (not long after the scene at Ernie’s, in fact): in it, Kim Novak visits a florist, a dowdy and somehow stern-looking woman in a blue dress.

Bereyter confessed that he had watched this scene countless times beforehand, without ever registering the florist. He saw Novak mutter something to the woman, and he saw the woman nod in return. That is all. But for some reason, that night, he finally noticed what he had hitherto always failed to: namely, that the florist is speaking. Far from simply nodding at Novak, the extra is saying something to Novak. He rewound the scene repeatedly, he told us, and squinted at the florist. What was she mouthing? What had she said? And would it be possible, Bereyter asked himself that night, he informed us this morning, to read her lips? After making various inquiries on campus, he eventually managed to meet a lip reader in the German department. She agreed to review the footage, and, within a week, she had delivered her results: the florist was mouthing All right.

At this point in his presentation, I actually picked up my pen, to try to scribble down — in the windowless Wolfsegg darkness — the phrase All right. But on a moment’s reflection I decided that it would not be worth the trouble. These two words — this accidental scrap of dialogue, sheer happenstance dialogue, caught on camera but otherwise unintended, the improvisatory dialogue of a dowdy woman in a blue dress — were nothing more than a retail cliché, the servile bromide that any florist would offer any customer. No insight could be gained into the film via this discovery. It made no contribution to Hitchcock scholarship. I was even almost embarrassed, for Bereyter. I even almost blushed, on Bereyter’s behalf. This was what he had to show for white dialogues, after years of research? The silence in the room was killing. Even Dzieza, Plunkett, and Guss — groveling there in the front row — even they must be feeling bad for Bereyter, I thought. Any fool could see that his project was a travesty, with zero scholarly value: that it was an autotelically archival project, whose results hardly mattered; that its only goal was the indiscriminate compilation of every extra’s on-set gibberish. Bereyter’s next example was no better. He screened for us a scene shot in a ballroom, during which he demonstrated that one dancer — a simpering man in a dark suit — could be glimpsed whispering something into the ear of his older dance partner, an octogenarian woman in a ball gown of pink taffeta, outfitted with a white tiara, perhaps the man’s mother-in-law, if not his own mother, Bereyter speculated, thereby attributing filial relations and an entire backstory to these utterly inconsequential non-characters. What the simpering man turned out to be whispering, Bereyter announced, was, If you think.

To my great shock, this second line was not greeted with abrupt and derisory laughter, but a seism of thoughtful murmurs, which spread backward through the audience from the front row. People were genuinely impressed. They were not merely humoring Bereyter, but were responding as if to some profound revelation. I alone (evidently) had to bite my tongue. I alone (evidently) saw white dialogues for what they were. This was nothing more than chitchat exegesis, a kind of crackpot cryptology, I thought, watching Bereyter smile in satisfaction, as he humbly waited out the murmur. He is a charlatan, I thought, why not close read the billboards, or the shop-window signage? Gripping my pen, I reflected that reading extras’ lips is no better than reading coffee grounds — it is superstition, pure cinemancy — and as Bereyter continued with his lecture, I even tried to jot down the phrase crackpot cryptology in my journal, a little something to confront him with during the Q&A. But in the darkness all I managed to scrawl were discrete stabs of ink, stark violent hieroglyphs against the paper. And what’s more, it occurred to me, setting down my pen, his methodology is not even (if I may put it this way) sound. For in addition to being useless, his white dialogues are unreliable. In addition to being meaningless texts, they are absolutely corrupted texts. By what criteria is his lip reader arriving at her results? Even the best lip readers can achieve only thirty percent accuracy, and to do so they must rely on extended exchanges, body language, and other kinds of semantic context. Lacking these nonverbal determinants, how is Bereyter’s lip reader supposed to distinguish between two identical sounds (two and too, for instance), or even between two pseudo-homophonic mouth movements? How was she able to tell that this dancer is mouthing all right, rather than all write, all rate, awe right, or something else altogether? How does she distinguish one bilabial fricative from another? One alveolar plosive from another? One close-mid central vowel from another? Could Bereyter really expect us to take this methodology seriously? No, I decided, scrawling a line back and forth in my journal, this so-called project could only be a diabolical joke, something on the order of the Sokal Hoax, cooked up by Bereyter to expose the risible state of contemporary film scholarship. I could barely believe that my colleagues — the same colleagues who have denied me tenure, referring diplomatically to my dearth of publications (in private they have not been so polite, I know, dismissing my single published article as obscurantist nonsense) — I could barely believe that Dzieza, Plunkett, and Guss were now allowing Bereyter to pull the wool so thoroughly over their eyes. Not only have they invited this mountebank to teach for the year, I thought, but here they are murmuring in approval at his utmost mountebankery, stroking their chins throughout this absurd presentation. He still has not moved on from the scene in Ernie’s Restaurant — they are all no doubt still listening to the woman onscreen. My article was not obscure. Titled Rear Window Vertigo, it was the only chapter of my dissertation to be published, and its thesis is that Vertigo is in fact a second act or secret sequel to one of Hitchcock’s previous films, 1954’s Rear Window. Both movies star James Stewart, and my article’s insight was that Stewart is not playing two distinct roles: rather, he is playing the same character in each film, or, more precisely, the same character in a single film, a four-hour film titled Rear Window Vertigo. In Rear Window, the first half of the film, Stewart plays a photographer and amateur detective in New York, under the name L.B. Jefferies. In the second half of the film, Vertigo, he plays a professional detective in San Francisco, under the name Scottie. Jeff and Scottie, my article reasons, can only be the same person, a Scottie-Jeff hybrid, comprising two split but reciprocal identities. It is as if, at the end of Rear Window, Jeff undergoes some kind of psychogenic fugue: forgetting both his name and his existence, he travels in an amnesiac trance across the country, from New York to San Francisco, from Rear Window to Vertigo, where he takes up a second life as Scottie, who is then compelled to repeat key details of Jeff’s repressed identity. How else to explain the uncanny continuities between these characters? For instance, their mutual fear of heights. Looked at one way, Jeff’s traumatic fall from the apartment building (at the end of Rear Window) is what triggers Scottie’s symptomatic acrophobia (at the beginning of Vertigo), when he finds himself dangling from a ledge for (what he does not realize is) the second time in his life.

The majority of my article is devoted to tracking down and demonstrating these kinds of correspondences, which I do ruthlessly, indisputably, despite the kneejerk know-nothing dismissiveness of Dzieza, Plunkett, and Guss. In an early scene of Rear Window, Scottie-Jeff is scolded for spying on his neighbors: another character reminds him that Peeping Toms are criminals, then says, I can see you in court now, surrounded by a bunch of lawyers in double-breasted suits. I would like very much for Dzieza, Plunkett, and Guss to explain this line to me. I would like for them to sit down and try to explain, one day, how this line of dialogue is not a vatic prevision of Vertigo, in light of the fact that Scottie-Jeff (who is actually employed as a Peeping Tom in this film) is summoned to trial following one character’s death, where, as prophesied, he is cross-examined in court, surrounded by a bunch of lawyers in double-breasted suits.

There is no other explanation. James Stewart has exited Rear Window for Vertigo. He has escaped the Rear Window bottle for the Vertigo bottle. No sooner has he left the Rear Window frying pan than he has entered the Vertigo fire. Neither Scottie nor Jeff but Scottie-Jeff. That was — is — the major insight of my article. And yet it is as nothing next to Bereyter’s insights, according to my colleagues, for my article is contaminated at the outset by its enabling methodological error. I am found guilty of ignoring the boundary line dividing these two films. Never mind the fact that that is precisely the point of my article, or that it is James Stewart himself who has ignored this boundary line. This is what counts for a methodological error, among my colleagues, rather than lip reading. This is what cripples a career tout court, among my colleagues, rather than charlatanry. But whereas I may not have coined a flashy term for my techniques, and whereas I may not have signed a publishing contract for my dissertation with the University of N — Press — as the irrepressible departmental gossip suggests that Bereyter has — and whereas I, in my mid-thirties, still untenured, largely unpublished, am about to be cast back into the void of the anoxic job market, at least I am on the side of Hitchcock. I at least am close-reading Hitchcock’s dialogue, dialogue that he approved in script, and not only that, but dialogue that he then directed the delivery of, and fastidiously positioned his microphones to record, and instructed his audio engineers to mix at a legible level, all so that it would play a definite and measurable role in the meaning of his movie. Unlike Bereyter, I am not engaged in some preposterous aleatoric hermeneutics; I am not attempting to somehow one-up the director himself, driven by scholarly hubris and an unsurpassed disregard for Hitchcock — not to say Hitchcock contempt, Hitchcock hostility, a transparently Oedipal and near-homicidal Hitchcock hatred — to ignore the dialogue of his design, rooting around instead inside his blind spots, hell-bent on hunting down any chance mouth movements that may have slipped into his film, between as it were the film’s cracks, beneath as it were Hitchcock’s watch, which — if you ask me (no one did) — is the methodological error par excellence. Yes, there are almost unthinkable levels of aggression wound up in white dialogues, aggression toward Hitchcock and aggression toward his films. Bereyter is trying to spy on Hitchcock, to expose his secrets. White dialogues are his wiretapping, as surely as he is Hitchcock’s J. Edgar Hoover. There is no ignoring Bereyter’s malevolence. It even puts me in mind of the patron saint of white dialogues, that villainous lip reader who — if not the first scholar of white dialogues in film history — is certainly the most infamous: namely, HAL 9000, the sinister sentient computer in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, whose cyclopean surveillance cameras — those exophthalmic crimson lenses, mounted on walls throughout the spaceship — are able to read the astronauts’ lips. Like HAL 9000, Bereyter always seems to be taunting Hitchcock (this taunt is the subtext of every white dialogue): Alfred, although you took very thorough precautions in the florist’s against my hearing her, I could see her lips move.

I look again at the white pull-down canvas behind Bereyter. The scene at Ernie’s is still flickering against it, and the woman at the bar is still mouthing her indecipherable message. Whether Bereyter has already read her white dialogue aloud, when I wasn’t paying attention, or whether he is still showboating by exhorting us to listen to her, I cannot discern. He appears to have moved ahead in his lecture, or perhaps he is on a tangent; at any rate he is now discussing the use of white noise in The Birds, in particular the cutting-edge sound design in that film, specifically how an electronically produced subliminal hum is amplified on the audio track during certain bird sequences, to create a suffocating silence as their signature. Ignoring him, I continue to watch the woman at the bar. Every four seconds or so the scene jumps back to the beginning, caught in its loop. In this way she is forced to keep restarting her dialogue, forever unable to finish, like some Sisyphus of speech. It is as though this endless repetition or eternal return of the sentence is itself the sentence she is serving, the chthonic contrapasso that has been meted out to her, upon her arrival in the underworld, I think. Sitting alone in my desk chair in the darkness, at the very back of this basement seminar room, thinking of the underworld, I notice in a distracted way — and for the second time this morning — the woman’s graying hair. It is then that the thought occurs to me: yes, I realize, this woman must be dead, long dead by now, her presence on the canvas spectral.

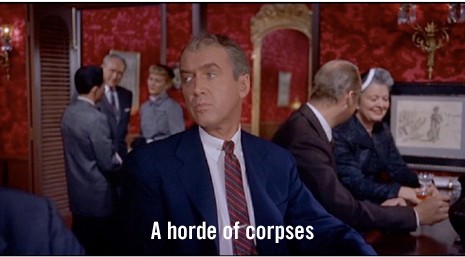

On the whiteboard beside the screen, Bereyter has not yet erased his works-cited entry. 1958. That is right: over five decades have passed since the filming of this scene, half a century, and even then she was already middle-aged. This woman on the screen before me, this woman smiling to her companion — mouthing something, rolling her eyes — this evident coquette, lush, and flirt, this actress, this extra, this filler, this specimen of white dialogues and therefore this woman whom Bereyter is exhorting us to listen to today, she is a dead woman. There is no getting around it. Bereyter has employed his German professor to read the lips of the dead. Whoever that actress was (her name will undoubtedly go unlisted in the credits), she could never have expected this outcome. When she agreed to occupy a barstool in the background of the new Hitchcock film, and when that esteemed Englishman directed her to speak freely, to simply improvise — no one would ever hear her, she enjoyed the privacy of silence; perhaps he even snapped at her as he said this, he was notoriously difficult with women — she could never have predicted that one day, half a century hence, who knows how many years after her own death, some smarmy scholar in a prep-school cardigan would be reading her lips. Whatever she said that day, she had surely assumed that it would remain a secret, whispered in confidence to her companion at the bar, her costar in silence. After leaving the set, she probably forgot the line of dialogue herself. And when she brought her family to see Vertigo on opening night, and pointed out her image on the silver screen — her son leaning toward her in the darkness, asking, What are you saying there, Mother? What were you mouthing that day? — it is likely, then, that her words were as much a mystery to her as to everyone else in the theater. That she was powerless to remember. That she had stuffed this message deep into the background bottle, down to its very punt, then promptly forgotten about it. Having consigned it to her unconscious, she must have ended up taking it — as they say — to her grave. It was to be the great secret of her life, this great silence, the private message that she had immortalized in four seconds of Vertigo: inviolably bottled until the end of time. Well, for half a century at least. She had not counted on Bereyter. She had failed to anticipate this eavesdropper, this grave robber, this bottle-opener and corkscrew artist, who decades after her death would break into Vertigo and extract her message himself. She had not foreseen that he would go so far as to hire a lip reader — that unscrupulous Teuton woman, without question wizened and sibylline, some curbside clairvoyant — to wrench this message from her dead lips. Messages of the dead. Of course, why hadn’t I thought of it before? That is surely how Bereyter intends to pitch his white dialogues to us this morning. As transmissions from beyond, coded messages from the underworld. His sheaf of white dialogues, there on the lectern before him, is as ridiculous as a Ouija-board transcript. When he reads from it next, in his best campfire quaver — in his horripilating Vincent Price whisper — that, surely, will be the climax and acme of his mountebankery this morning. Listen to her, he will intone to us in a hushed voice, and hear the messages of the dead. Listen to her!, he will then boom out at us from the lectern, and behold this signal from beyond, which we have recovered from the white noise of death. There is to be no limit to his presumptuousness this morning: not only a savant, but a visionary; not only a pedant, but a necromancer. That is the raison d’être of his white dialogues, necromancy pure and simple. This woman at the bar cannot be the only corpse in Vertigo. After half a century, most of its cast must be dead. James Stewart, I know, died of a pulmonary embolism in 1997. The florist is obviously dead, and the simpering dancer too (to say nothing of his ancient mother-in-law, or mother, who probably perished in the parking lot mere seconds after stepping off set). Kim Novak alone (evidently) is not yet dead. But as for everyone else, almost every other extra, they are all cadavers now, if not completely decomposed. Skeletons in their coffins, I think, in an utterly morbid tone of mind-voice, and this thought seems to penetrate the image onscreen like an X-ray, transforming the very extras at the bar into a band of skeletons, such that the restaurant strikes me for a moment as the most grotesque apotheosis of death, a horde of corpses.

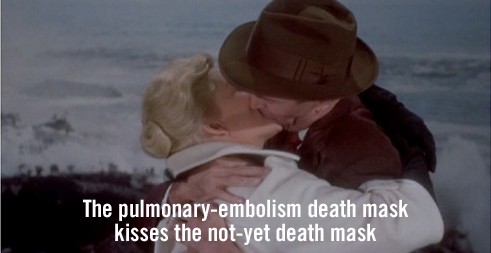

James Stewart with his haunted expression is dead, and the balding man at the bar behind him (his blonde hair brushed back from his calvity) dead, and the romantic trio in the background (the woman in the dovegray pea coat, her date in his charcoal suit, the tall gentleman chaperoning the two of them) every one of them dead, struck down by the last half century. Chatting convivially on set, they too are likely victims of Bereyter’s grave robbery. For that is what his white dialogues project amounts to, in the final analysis: already hermeneutically useless, already methodologically unsound, it is also, after all that, sheer vandalism; it is also, on top of everything else, the most depraved and tasteless tomb raiding. I watch the dead woman at the bar. I imagine her son watching this movie, now that she is dead. He must replay this scene on repeat as well, from time to time. Scrutinizing her lips. Auscultating her silence. Trying to puzzle out what she said. If nothing else about his mother is certain, these four seconds present an irrefutable truth: one day in 1958, on set in Ernie’s Restaurant in San Francisco, she was there. Her klieg-lit body reflected luminous rays, which were captured in the canisters of Hitchcock’s camera, and with the breath of her lungs she uttered various words, which no microphones recorded. That is the paradox of film: on the one hand, she is dead; but on the other hand she is still — inside these four seconds — alive. Sitting at the bar, flickering on this screen, she is not yet dead. It is 1958, her death lies beyond the horizon of the film, she has forever yet to die. She is dead, and she is going to die, her son must mutter softly to himself, while rewinding this scene on the DVD, I think, watching her from my place in the desk chair. This movie, for him, must be no different from any other family photograph or home video. It is a photographic document of his living mother: the treasury of her rays, a last surviving locket of her light. The one thing it did not preserve — the one thing this footage cannot tell him — is what she said that day. After years of curiosity, her voiceless words must have taken on, in his imagination, the proportions of a deathbed benediction. What had she said? What had she meant to tell him? He would never know. And so thank God for Bereyter! Thank God Bereyter has finally arrived at Vertigo, crowbar in hand, to pry the lid off this poor woman’s sepulcher. Thank God he has crawled deep inside — accompanied by his ghoulish lip-reading Igor — to plunder her message once and for all. And he won’t stop there. No, next he will publish his results with the University of N — , ensuring that this bereaved man can one day flip through the pages of Bereyter’s book and find his dead mother’s image printed in a screen capture, with an italicized caption floating beneath her face. At long last, at this late date, he will be able to see — laid bare in all their banality, their bathos — the words his dead mother spoke that day: Yes, I’ll have another; No thank you; All right. If I could see at all in this darkness, I think, gripping my pen pointlessly, if only I could see, I would sketch a quick caricature of Bereyter now. Yes, that would give me ultimate pleasure. To portray Bereyter as he truly is: not in his prep-school cardigan, but in his khaki bush jacket and pith helmet; not with his sheaf of lecture notes, but wielding his pickaxe, his loot sack, as he tears open this poor woman’s sarcophagus. For Vertigo is her pyramid, as surely as Bereyter is her Howard Carter. Of course all films — but especially old films — are pyramids, I realize. Of course all films — but especially old films — serve a preservative function: they exist first and foremost to freeze-dry their actors’ bodies, safeguarding them from destruction. I know this as well as anyone. Actors’ heads are shrunken in the formaldehyde jars of close-ups. They are embalmed within the film, mummified by the film. That is why it is possible to view all films — but especially old films — as mummy films. Photography began, after all, as a mummifying technology, a 19th-century advance in mankind’s age-old mummy complex. With each passing era, I know, mankind has perfected the perverse art of preserving corpses. First the mummy, then the death mask, then the photograph. After the photograph, there remained only one logical step: the moving image. From Egypt down to the Egyptian Theater, there has been a direct and unbroken lineage. Every movie is a pyramid, stuffed tight with mummies. Every movie is a mobile gallery of death masks. I have always felt this way. Whereas most viewers see actors’ faces, all I see are death masks. Whereas my colleagues are liable to say, That actor did a fine job, I always have to stop myself from saying, That death mask did a fine job. Frankly, my dear, I hear one death mask say to the other death mask, I don’t give a damn, and I watch in horror as tears stream down the second death mask’s face. With Vertigo it is no different. I see the James Stewart death mask kiss the Kim Novak death mask. I see the pulmonary-embolism death mask kiss the not-yet death mask. Even though Kim Novak is still alive, her face in this movie is no less grotesque a death mask: it is a twenty-five-year-old’s death mask, a simulacral death mask, waiting patiently for its living counterpart to die. Meanwhile, in the backgrounds of these scenes, there are whole crowds of death masks, every shot a charnel house of death masks, the unmummified or half-mummified faces of extras. It is as in any pyramid: here too there are hierarchies of preservation. At the pharaonic apex, there are Stewart and Novak, painstakingly embalmed. Not only their images, but their voices as well, have been extended into eternity. Below them are the extras, their servants and courtiers, who have been permitted to disintegrate. Sometimes the camera does not bother to preserve these extras’ faces, only a passing shoulder, a half-turned back. Sometimes their voices have been excluded from the audio track. Everywhere the movie echoes like a mausoleum with the sounds of Stewart’s voice, which drowns out all the extras’ voices, such that we cannot hear what these people are saying. For over half a century, their speech has remained invisible: un-listened-to, and perhaps unlistenable, buried beneath the phenomenal threshold of the film. Their names are not even listed in the film’s credits. In these so-called credits — in fact they are necrologies — in these crawling columns of the dead, the extras do not merit registry. They are the plebeian dead, anonymous corpses. Faceless, mute, they have been lost to nameless oblivion. Now, half a century later, Bereyter has arrived to disturb their rest.

At the lectern, Bereyter is silent. He frowns down at his notes, apparently pausing for emphasis. Then he glances up and clears his throat: If you listen to this woman, he finally announces, you will hear only the surrounding drone of Ernie’s Restaurant, a low monotone, not unlike the white noise in The Birds. But this white noise, he goes on, is diegetic, it is as deafening for the characters as it is for us. This man at the bar, he says, this woman’s companion, he says, he is leaning forward to hear her, in fact must be struggling to hear her, and perhaps he is even reading her lips himself. Bereyter smiles coyly here, an expression I can detect even from the back row, and which fills me — even at a distance of a dozen desk chairs — with revulsion. In forcing us to squint at her lips, he continues, the film gives us a deaf person’s viewpoint. In the background of this talkie, we witness a return of the repressed of the silent era, a holdover from Hitchcock’s own career in the silent cinema: like June Tripp or Marie Ault in The Lodger, this actress portrays a character whose lips must be read. Which is all the more remarkable, Bereyter concludes, when we finally discover what she is mouthing. For she is the first self-conscious authoress of a metafictional or metatextual white dialogue, a self-referential white dialogue. Bereyter holds up his left hand now, to indicate a direct quotation, and then — looking down at the lectern — begins to read: Read my lips, this woman says, Bereyter says. It’s Jeff.

There is another excited murmur in the audience. Bereyter projects his voice over the uproar: She has embraced her silence, he booms out at us from the lectern, qua white dialogue. Knowing that Hitchcock has placed her in a zone of white noise, he says, she commands her companion to read her lips. At this point Bereyter presses on with his lecture, expatiating on the significance of this utterance — this moment of meta-muteness, as he calls it, where we encounter for the first time the self-aware voiceless voice — which discovery he is somehow attempting to parlay into a scholarly dispute vis-à-vis the vococentrism of Michel Chion. But I am no longer listening. I am still watching the clip on the screen. Bereyter, having not yet reached his next example in Vertigo, leaves it looping on the pull-down canvas behind him, and I cannot tear my eyes from the dead woman. Read my lips, she is saying, it’s Jeff. And when I study her lips, yes, it is obvious, that is what she has been mouthing all along. Read my lips, it’s as plain as day. Read my lips, I read, pressing my body against the back of my desk chair. It’s Jeff, I read, pushing against the edge of my writing tray with both hands. Bereyter babbles on at the lectern, oblivious. He has no clue what he has uncovered. The dead woman looms huge behind him — spectral, repetitive, looping her impossible message over and over — and Bereyter gestures left and right, lecturing to his audience. He is incapable of appreciating the significance of his own discovery. For while looking right at James Stewart — there is now no denying it — this woman is mouthing, It’s Jeff. She is referring to Stewart, not as Scottie, but as Jeff: his repressed name, his Rear Window name. It is as if some background actress, some extra from Rear Window, has followed James Stewart into the film. As if this middle-aged woman in her blue suit has herself traveled all the way from New York to San Francisco, from Rear Window to Vertigo, shadowing Scottie-Jeff to Ernie’s. Spotting him there, she identifies him. There is no other explanation. She can be referring only beyond Vertigo, outside Vertigo, back toward Rear Window, the secret provenance of Scottie-Jeff, and so there is no way even to understand this extra’s exophoric utterance — It’s Jeff, It’s Jeff — unless you take Rear Window into account. Read my lips, it’s Jeff. This message she is mouthing, directly toward the screen, is meant not for her companion, but for the audience. She is telling the audience — she is telling me — that Scottie is an impostor, that he is actually Jeff, a hybrid or chimerical Scottie-Jeff, she is confirming my theory in the most incontrovertible terms. That is the incredible, earth-shattering message she is mouthing, and yet Bereyter — the imbecile! — can think of nothing but scoring petty points off Michel Chion. It is undeniable now: there is no border between these films. James Stewart and this extra have both succeeded in escaping. They have left the Rear Window bottle for the Vertigo bottle. They have abandoned the Rear Window pyramid for the Vertigo pyramid. And what is to stop her, I wonder — regarding her image warily on the screen — what is to stop her from leaving the Vertigo bottle for the Wolfsegg bottle? Now that Bereyter has uncorked her? What is to keep her from escaping through the adit of the projector shaft, and from emerging (slowly but surely, in Clegg’s phrase) out of the movie and into the room? I close my eyes, unable to watch, and by the time I reopen them I have stopped breathing. But she is still sitting there of course, trapped on the flatness of the screen. The dead woman is looking right into my eyes, telling me again and again to read her lips, repeating over and over that it’s Jeff. I am entirely too agitated to stay. Without taking my eyes from hers, I rise from my desk chair in a single stealthy motion. Except I must make a noise, for the man a few rows ahead of me turns around. Seeing me standing there, he holds up an index finger, imploring me to wait a moment, then twists in his seat to grab something from his writing tray. He reaches across the aisle to hand it to me: a piece of paper. Taking it, I nod my head in thanks and sit back down. I don’t have time for this, I tell myself, even as I am placing the paper on my desktop; I have to get out of here, even as I am smoothing it flat with my hand. It is a column of three photographs, screen captures from Vertigo, with italicized captions printed beneath them. Bereyter’s transcript. He has given me the lip reader’s sample, which has been circulating the room all morning. I scan the extras’ faces, looking for any refugees from Rear Window. By the flickering of the projector, I squint down at the captions, straining to read their white dialogues.

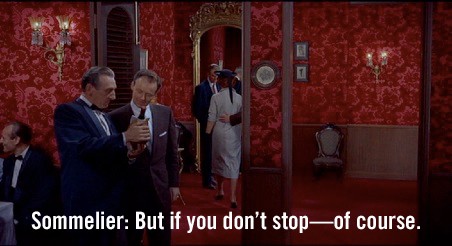

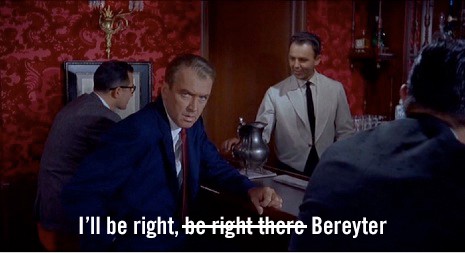

I recognize the scene immediately. It occurs midway through the film, during Scottie-Jeff’s return to Ernie’s Restaurant. Again he takes his place on the barstool, peering hauntedly off-camera. Again the corpses around him mutter silently to themselves. I skim their captions quickly, three times in succession. My eyes fly over them, looking for any clues. But none of them call out, It’s Jeff! Instead, the sommelier confers with the host. The barman makes small talk with his bespectacled patron. But if you do not stop, says the one; I’ll be right there, says the other. As for Diner 1 — who I can only presume is the wolfish man in the black bowtie, seated beneath the back wall’s dinner tray and decorated by the electric candle flame (it flickers above his suit’s breast pocket like a boutonnière) — he is holding forth at his table, grinning mischievously at the woman seated opposite him. We see you, he tells her. We see you, he says. I smirk down at the transcript. Bereyter could not have written less meaningful white dialogues himself. And yet, I think, rereading the captions for the fourth time, there is something not quite right here. Something in each screen capture — something ineffable — is off: each frame before me bears some uncanny incongruity. It is impossible to place, but it is just as impossible to ignore. These cannot possibly be the words the extras are mouthing. The sommelier, flaunting a wine bottle in his hands, admonishes the host with this enigmatic ultimatum: If you do not stop, he says… But stop what? Meanwhile the barman assures his customer — even as he is walking away from him — I’ll be right there, be right there. Then there is Diner 1: he tells the woman, We see you, when no one at the table is even looking at her. The right-hand couple leans toward him. He himself is glancing — grinning — at a point over her shoulder. There must be some mistake. The lip reader must have misread their lips. The barman could very well be mouthing, Pee right there. I mouth these syllables to myself, alone in my desk chair in the back row, testing out the alternatives. Fright there, I mouth to myself, and then, Bright air. Bright star, I mouth to myself, and then, Be right air. Be right air, Be rye tare, I mouth to myself, as a chill runs through me. Be reyt er, I mouth to myself, gripping my pen, Bereyter. Bright air, I mouth to myself, Bereyter. Bright air, Bereyter, I mouth to myself. Bereyter, would I were steadfast as thou art. Pen in hand, I scrawl a line through the italicized caption, forcefully crossing out the second be right there. Beside it I write — as best I can in the darkness, my hand trembling — Bereyter.

Yes. Yes. It is insane, but it is obvious. In face it is even more obvious than it is insane. That is what the barman is mouthing. He is speaking not to his customer, but to Bereyter. He is on his way — not to his customer — but to Bereyter. And the other extras too. For instance the sommelier with his wine bottle, mouthing But if you don’t stop. Who else could he be addressing, besides Bereyter? What else could he possibly mean, besides, If you don’t stop disturbing our rest? If you don’t stop uncorking our deaths, the silent bottle that our death is, as vulnerable as this bottle that I hold in my hands? If you don’t stop, of course, I’ll be right there, Bereyter. We see you. I look down at the transcript in horror: Diner 1’s beady eyes stare far past his companion’s shoulder, peering out of the paper to pierce my own. Yes, it is unmistakable, he is looking straight through the camera and has been looking through that camera for fifty years, patiently, unblinkingly, waiting for the day when someone would finally meet his gaze. When someone would trespass this border and demolish this fourth wall. We see you, he says, We see you, speaking not just for his tablemates, but — it dawns on me — every single extra in Vertigo, such that now, all at once, the grin on his face takes on the most sinister dimensions. My God, I think, staring down dumbfounded at the transcript on my desk…They are coming. At just this moment, the lights flash on. I blink furiously, blinded by the sudden fluorescence, and I see that Bereyter — having stepped from behind the lectern — is now pushing up the black sleeves of his cardigan. He is initiating the Q&A. Behind him, the white pull-down canvas is blank; above me, the projector is no longer whirring. A hand shoots up in the front row, either Dzieza’s, Plunkett’s, or Guss’s, it does not matter. Bereyter nods, and, in a barely audible voice, the interrogator asks some flattering question: What will this mean for film theory? he is probably asking. When can we expect your book? he is probably asking. I cannot stand to listen. Bereyter has invited the wrath of the dead upon all of us. He has broken into the mummy’s pyramid, broken the seal on the mummy’s tomb. He has called down the mummy’s curse on all our heads, and no one else understands this. Oh, I have questions for Bereyter all right. I have been storing them up all morning. Gripping the pen in my hand, I begin to write them in my notepad, just beneath the word bottle. My hand scribbles compulsively, building up its case against Bereyter. If I don’t stand up to him — confront him with the monstrousness of what he’s done — no one will. At the critical moment, I will have to rise from this seat at the back of the room, where I have gone unnoticed in the shadows, and then I alone (evidently) will have to speak truth to Bereyter. Yes, yes, Bereyter will call, you there, in the back, and a gasp will go up in the front row — escaping in unison from Dzieza, Plunkett, and Guss — when they see that it is me, that I have been here all along. Yes, I will hiss at them, it is me, and I will astonish them each in turn with what I have to say. I will force them to consider once and for all the unanswerable questions that Bereyter’s recklessness raises, the questions that my hand — even now — is scrawling in my notebook beneath me. Have you no decency, Bereyter?, it writes. Don’t you know what will happen, Bereyter?, it writes. Are you not wiretapping the dead, Bereyter, spying on their secrets, Bereyter, and spreading them high and low, Bereyter, not only to us here today, but to your editors at the University of N — as well? How did you expect the dead to react? Has it not occurred to you, it writes, that they have already given you ample warning? What did you think would happen, when you and your lip reader went uncorking the dead? When you opened the lid, not on Pandora’s Box, Bereyter, but on Pandora’s Bottle? Not on Pandora’s Pithos, Bereyter, but on Pandora’s Pyramid? Bereyter, Bereyter, what have you done? I let the pen fall from my hand. It goes rolling over the side of the writing tray, clattering to the floor. Rising to my feet, I grip the desktop to steady myself, and concentrate all the energy in my being. Yes, I hear Bereyter call from the front of the room, you there. In the back.

End

Acknowledgments

This story borrows liberally from the work of several film theorists. Here’s a list of my conscious thefts:

- The “Rear Window Vertigo” reading is entirely Jalal Toufic’s, from his essay of that name, included in Two or Three Things I’m Dying to Tell You (2005).

- The phrase (and the concept of) ‘the mummy complex’ is André Bazin’s, from his essay “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” included in What Is Cinema? Vol. 1 (2004).

- The formulation “___ is dead, and ___ is going to die” (as well as some of the surrounding language in that passage: ‘luminous rays’; ‘treasury of her rays’; etc.) is Roland Barthes’s, from Camera Lucida (1981).

- The Michel Chion quotation is cobbled together from two separate passages in The Voice in Cinema (1999).