Reading Lists

Who Was the First Asian American Author You Read?

Alexander Chee, Monique Truong, and 18 other writers on the first time they saw themselves reflected in literature

Popular culture in America rarely looks Asian. Only one percent of Hollywood lead roles go to people of Asian descent, and the canon of “Great American novels” never includes Asian authors). Even when Asian characters are featured in books or movies or prime time TV, it’s often as the bumbling sidekick, evil warlord, suffering refugee, or silent manicurist—or just turned into white people in yellowface (I’m looking at you, Scarlett Johansson, Tilda Swinton and Emma Stone).

But sometimes—and, thankfully, increasingly often—we are seen, especially when we take matters into our own hands and create stories and characters that reflect the diversity of America. Feeling seen is a powerful thing. For Asian American Heritage Month, we asked authors that we admire about their first experience reading work by an Asian American writer, to highlight the importance of representation in American literature. Here are the trail-blazing Asian American writers made it possible for a new generation to see themselves as writers.

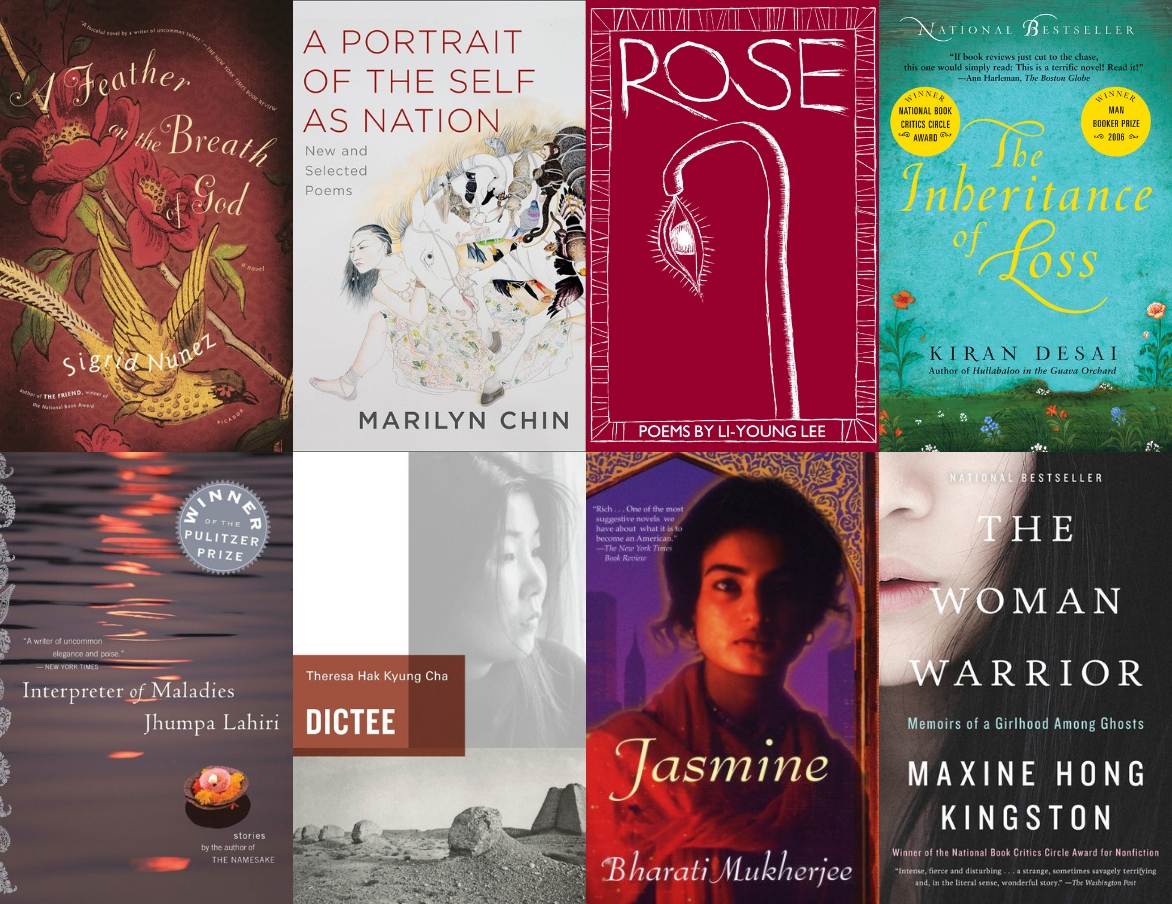

Mira Jacob: Jasmine by Bharati Mukherjee

Jasmine by Bharati Mukherjee was the first book I ever read about an Indian woman in America, from her point of view. That meant she wasn’t the punchline or the sidekick or the nanny, but a fully realized person, one somewhere between my mom and I in age and experience. I remember putting the book down and thinking, whoa, is this what it’s like for other people who see themselves everywhere? Is this what it’s like to have your interiority externalized by someone who isn’t you, to have art that was made to represent you? It was such a new and wondrous feeling.

Alexander Chee: Dictee by Theresa Hak Yung Cha

Recently I was in a bookshop in Oamaru, New Zealand, and came across a copy of Dictee by Theresa Hak Yung Cha. I have a copy but I bought it all the same. My husband had come found it first, drawn to the cover because, as he put it, “she looked like your grandmother.” A similarity I’d observed also, but never named. I have been re-reading it as a result as I travel here, and I love the way it remains as radical a text as it was when I first found it, daring to hold a space open somewhere in between several genres, and to let tensions remain unresolved, or ambiguous, to pursue if not the articulation of the inarticulate, then, to let the reader experience what is inarticulate within themselves still in a space that makes room for it or even values it.

To the extent I ever experienced it at the level of representation, I think of it as a text that gave me permission to be weird on the page, to speak to ghosts, to inhabit realms we view as “remote” or “inaccessible” like they are next door. It was a boldness, the insistence on recombining the material of several cultures in order to make meaning and to insist on it even, at the level of the sentence and the page. Cha wasn’t making any kind of conventional “record” of her life this way, but instead was writing into her imagination, finding heroes there like Joan of Arc and Yu Gua Soon and imagining the text as a space they could inhabit and even prepare something new. It is an invocation, a ceremony, an experimental film rendered in text. And as I prepare for my third novel, it is a perfect companion again, just as it was when I was a student.

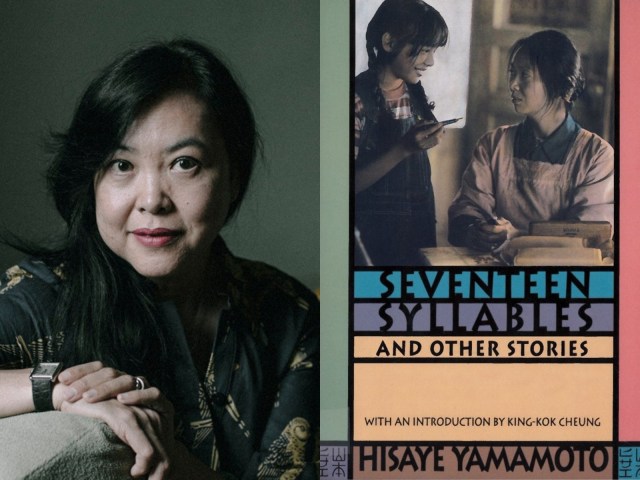

Monique Truong: “Yoneko’s Earthquake” by Hisaye Yamamoto

I am a novelist, but the form that I most admire is the short story, as it depends on concision and insinuation, a combo that I aspire to within my own writing. I read “Yoneko’s Earthquake” by Hisaye Yamamoto (1921-2011) in my sophomore or junior year in college. Not the first work by an Asian American that I had read, but, as with Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior, it has stayed with me, instructing me in terms of substance and craft with every re-reading. Written in 1951 and set in 1933, it is the earthquake to come—the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II and the resulting near destruction of this community—that haunts ten-year-old Yoneko’s story of family upheaval.

Read it and you will see how the longer arc of history—what the reader possesses and the characters do not—can be used by a writer to infuse each act and detail of her narrative with significance and subtle weight. What Yamamoto teaches me, then and now, is how to use this history in order to create a double narrative—a double jeopardy for her characters, as it were. Yamamoto also teaches the importance of knowing Asian American history because without it, I would have had a lesser, only partial understanding of “Yoneko’s Earthquake.” Devoid of explicit foreshadowing or heavy-handed exposition, the story, however, does not aim to teach this history to the reader. Perhaps that is Yamamoto’s most important lesson: literature by Asian Americans is not here to provide a service or to enlighten, functioning as a quasi-native guide or cheat sheet to history. Literature is a participatory act. As a reader, you have to step up and do the work. That seems fair to me.

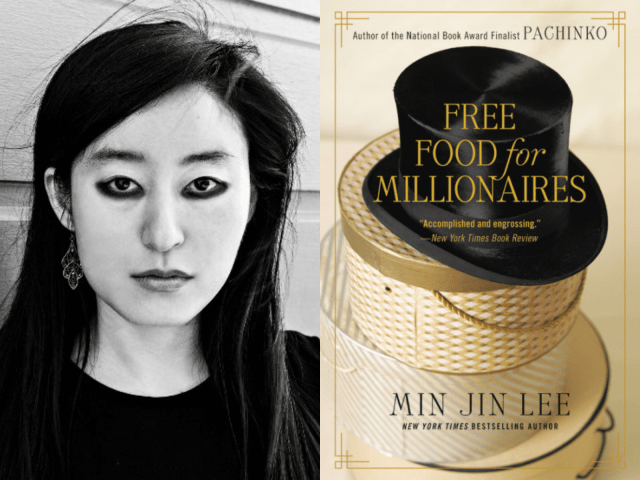

R. O. Kwon: Free Food for Millionaires by Min Jin Lee

I didn’t start reading Korean American writers until after college, which felt, in many ways, so late. But once I’d started, I really got into it. I can’t quite recall whose books I encountered when; I think of it now as a glorious post-college feast, a jumble of books by Alexander Chee, Susan Choi, Marie Myung-Ok Lee, Chang-rae Lee, and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. There was also Min Jin Lee’s first novel, Free Food for Millionaires, which a friend handed to me after we’d met for a drink. “You should read this,” he said—a little shyly, maybe because he wasn’t Korean, and he didn’t want to imply that I, also a Korean, would particularly want to read the book. But I did; I do; I read it immediately, through the night and into the morning, this compelling, profound story centered on a Korean American woman trying to make a life for herself. Maybe I read it at exactly the right time.

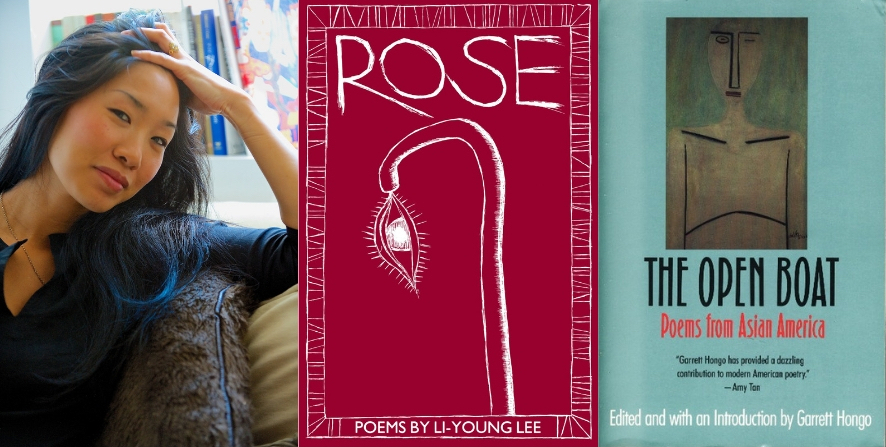

Tina Chang: Rose by Li-Young Lee and The Open Boat: Poems from Asian America edited by Garrett Hongo

In college, I began to feel passionately about writing poetry. The problem was, I had no role models. I hadn’t encountered Asian American writing and it was difficult to imagine what my life as a writer might look like. When I began my poetry studies in graduate school, my first class focused on established poets and their first poetry collections. It was then that I encountered Li-Young Lee’s book, Rose. I turned to the back cover and I may have gasped. The back cover featured a striking Asian American man. The man could have been a family member, a close relative. The feeling of kinship was overwhelming.

Opening the book Rose felt like a miracle. Lee’s primary subjects were his Asian American background, romantic love, and a deep yearning for the spirit of a father long gone. He approached language, culture, identity in ways I think I had only dreamed of. His voice was meditative, serene, grounded yet otherworldly. There seemed to be an internal world before Li-Young and after Li-Young. The world after reading Li-Young’s work was full of permission, celebration, and full commitment to the Asian American themes I only dared to ponder. It was around the same time that Garrett Hongo’s anthology The Open Boat: Poems from Asian America was published which gathered voices such as Jessica Hagedorn, Marilyn Chin, David Mura, Arthur Sze, Agha Shahid Ali, among so many other luminaries. The gathering of these Asian American poets breathed life into me and from that moment my writing life was born.

“Windblown, a rain-soaked

bough shakes, showering

the man and the boy.

They shiver in delight,

and the father lifts from his son’s cheek

one green leaf

fallen like a kiss.”

– Li-Young Lee, Rose

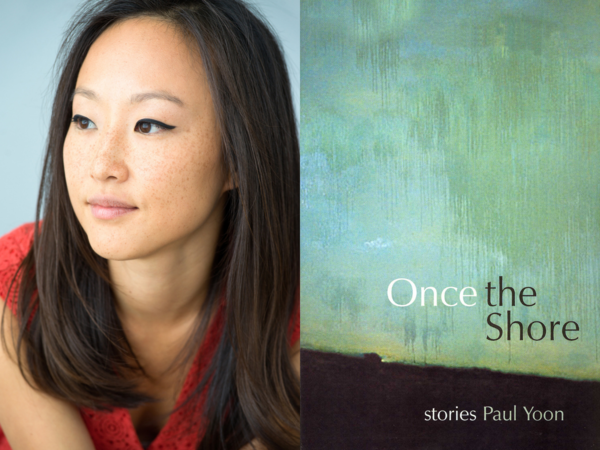

Crystal Hana Kim: Once The Shore by Paul Yoon

Reading Paul Yoon’s debut short story collection Once The Shore changed me. I was in college, taking as many writing classes as possible and yet afraid of what it would mean to commit to this impractical, obsessive, unrelenting love of mine. As I read Paul’s stories about characters on a South Korean island, I felt my world of literary possibility expand. What relief. Here were the stories I didn’t know I needed—of love and mourning and family, but also of Koreans haunted by the effects of Japanese occupation and the Korean War. Until then, a part of me had been afraid of what it meant to be a Korean American writer. As an English major, I had been fed the white, western canon. Paul’s book broke something loose in me. His spare, evocative sentences gave me hope.

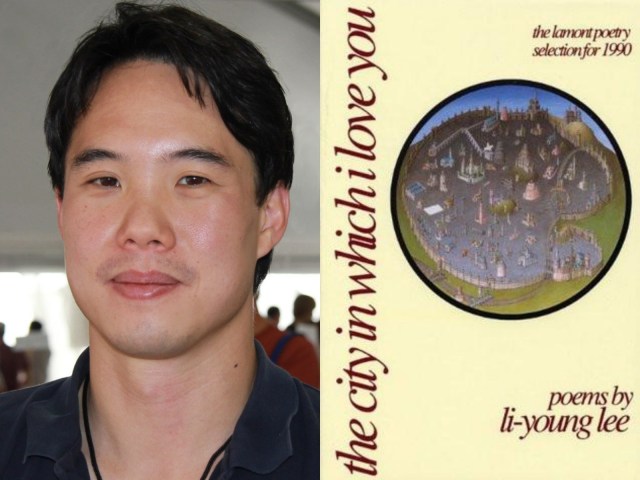

Charles Yu: The City in Which I Love You by Li-Young Lee

At Berkeley, in the early 1990s, I was introduced to the work of the poet Li-Young Lee. I was taking undergraduate poetry workshops and reading from the Norton Anthology, and that was great but it was also like going to the museum, seeing the poems that were already canonized, encased in amber and far away in space and time. There were certain books that students would talk about and pass around, like: here’s the real stuff. Lee’s collection, The City in Which I Love You was one of those books, and I remember the experience of encountering Lee’s voice (in my head, I mean) for the first time. It was music. It was intimate and gorgeous and perfect. And the fact that an Asian American man had written these poems–his face on the back cover–that was inspiring. He was someone I could model after, proof that it could be done. The idea of becoming a writer, for me, went from being an abstract, airy dream to a concrete possibility, however unlikely.

Meredith Talusan: “This Blessed House” by Jhumpa Lahiri

I forget which Boston library it was where I first encountered Jhumpa Lahiri, but I do remember the long wooden desks of a periodical room, a whole section devoted to literary journals. I’d arrived on a hunch because after nearly a lifetime of reading books, from a childhood learning English in the Philippines to becoming a literature major in college, it only just occurred to me that I could maybe write myself.

After more than a decade of literary education, I’d never read a story by an Asian American writer. So I wondered if such writers existed, and I perused those journals to find them. I somehow came upon a red volume of a journal called Epoch, and found a Lahiri story called “This Blessed House,” about the cultural conflicts between a newly-married Indian couple that felt both delightfully novel and intensely familiar. I looked for Lahiri’s stories in other journals, found in them people I could easily know in situations I could well envision, except that in her hands, their experiences transcended their own lives to reveal profound truths about the conflicts, griefs, and heartaches of living between continents. Jhumpa Lahiri was the first author who made me feel that I could also write, and I continue to marvel over her uncanny worlds.

Mary H.K. Choi: Claudine Ko

“See, I was never one of those Asian chicks who grew up wanting to be white. And I like to eat, I like having an ass. I’ve never felt the need to change my looks from straight-up milk-and-rice-fed Chinese girl, not even with makeup.” “A Woman’s Ugliness Cannot Be Forgiven.”

Claudine Ko for Jane Magazine, August 2002

Okay, so I don’t know that this is literature and I can’t say that Jane Magazine in the late-nineties and aughts was my first experience reading an Asian American writer but for me it was easily the most informative.

I loved the conspiratorial tone, that super-bloggy voice, the self-obsessed lens. Sure, it reads extremely late-nineties and aughts—breathless and oblivious compared to the urgency of a world on fire in a 24-hour-news cycle like now, but the lens for me was key. I knew what Claudine Ko looked like. She was constantly in the magazine. As was Stephanie Trong and Tina Chadha and that clean blew my mind.

They constantly talked about themselves. Their bodies, their butts, their thighs, their skin, their bellies. What they ate, how they decorated, how to fake lofty conversation, they taught me to drink wine out of tumblers instead of stemware (not because we were chic but because we were clumsy) and how to make dinner for one.

Ko wrote about Yayoi Kusama, Maggie Cheung and whatever was up with eyelid glue but she also wrote about Sofia Coppola, Rick Owens, skater girls and the women who were sexually targeted by American Apparel founder Dov Charney. His vile behavior during her reporting is what she SEO’s for most readily when you search for her name and “Jane” but that’s not what I remember Ko for (though her matter-of-factness and preservation of agency astonished me at the time).

As a fashion student with an eating disorder who’d been fed a steady diet of American Vogue, W, and L’Officiel, whose parents and parents’ friends constantly remarked on her appearance, Ko was like me but also so not like me. The quote above is from her story on cosmetic surgery in Korea and her attitude rearranged my thinking. It would heavily influence the way I would think, write and write about thinking when launching my own magazine Missbehave a few years later. It wasn’t just that she lived in New York, worked at a glossy and was Asian. It was her confidence. Her mettle. It’s that she seemed to possess a quality that I thought was relegated to white girls with demonstrative parents—she liked herself and stood her ground. I wanted that. Some days, I still want that. That I knew to want it then is the gift.

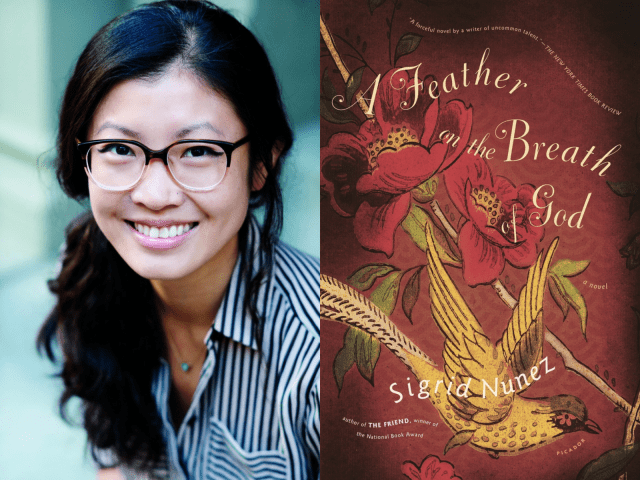

Weike Wang: A Feather on the Breath of God by Sigrid Nunez

Sigrid Nunez was my MFA professor and mentor. She won this year’s National Book Award for her astounding novel, The Friend, which I also highly recommend. Nunez is a writer I will be following for the rest of my life. I will read anything she writes, really. Stories, essays, book reviews, her prose is nothing short of excellent, imbued with humor and intellect, beauty and style. The first book of hers that I read was her debut novel, A Feather on the Breath of God. During that time, I was in the midst of my MFA. I had not read much before and certainly not any Asian American fiction. The first chapter of her novel centers on a Chinese father and a daughter’s relationship with this stoic and mysterious man. Needless to say, the story resonated with me, from its indelible details to its unique structure. Each chapter—there are only four—functions as both story and portraiture, the narrator comes of age and yet continuously dips back into memory, scenes explode on the page with vibrancy and urgency, momentum, yes, and often I would read a paragraph and have to set the book down as my heart would be racing from the force of her inimitable voice. A Feather on the Breath of God did so much for me at a time when I did not think I could write. What did I have to say? What could I do in prose? From Nunez, I learned it is rarely about the what, it is about the how. It is about a writer’s mind and her ability to continuously surprise us within the language itself.

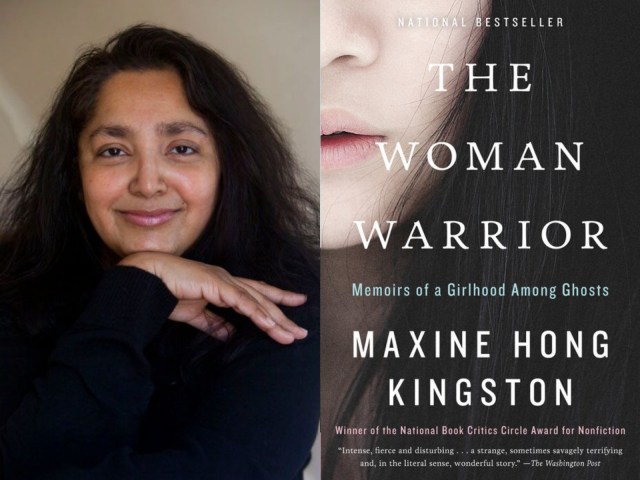

Bich Minh Nguyen: The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston

Growing up in a mostly-white, conservative town in Michigan, where my refugee family was resettled after the end of the war in Vietnam, I understood isolation, racism, and the demand to assimilate long before I had any words to describe them. In school we were assigned the usual kind of books: Gatsby, Animal Farm, The Scarlet Letter, Ethan Frome. Whiteness, and the diminishment if not outright erasure of anything else, was the curriculum. It wasn’t until I got to college and took a class in Asian American Studies that I read books by Asian American writers. Before that, I didn’t even know such a thing could be done.

I went to college in the 90s when people didn’t say I felt seen. If we had, all the Asian Americans I knew would have said that about The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston. The experience of Chinese Americans is not the same as that of Vietnamese Americans, but the overlap of understanding—isolation, racism, the demand to assimilate—more than resonates. In being seen, in seeing Kingston’s words on the page, I understood that maybe I could write my own experiences as well. It’s such a simple, fundamental thing, how seeing possibility creates more possibility. I’ll always be grateful to The Woman Warrior for that.

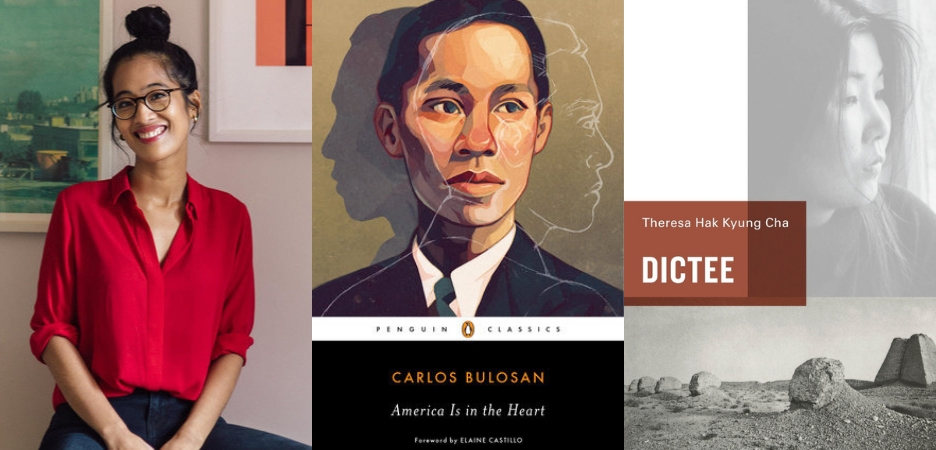

Elaine Castillo: America Is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan & Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

I remember the first time I read a book that contained characters who resembled the people in my own life: it was Carlos Bulosan’s America Is in the Heart, the seminal epic about immigrants from the rural poor of the Philippines (specifically, the area where my own rurally poor mother grew up) who struggle to make lives as migrant laborers along the American West Coast. It’s a book that still stays with me—and thanks to the era-defining work of Elda Rotor at Penguin Classics, it is being reissued this spring along with three other undersung classics of Asian American Literature. I was privileged enough to write the new foreword for America Is in the Heart, and it’s a book I hope will find new readers in this generation and beyond.

But it’s not the “first time” that came to mind when I was invited to write this feature. The readerly first time that came to my mind was the first time I read writer, artist and filmmaker Theresa Cha’s genre-busting masterpiece, Dictee. I think I was in my first year of college, maybe second, and Dictee was one of those formative books that blew my head wide open. Veering between prose, poetry, photography, and pulling from the devices of conceptual art, historical writing, autobiography and fiction, the book was as formally daring as it was intellectually and sensually exhilarating, especially to an impressionable young reader and writer. It was also one of the first times I was able to imagine a throughline of formally experimental and avant-garde writing that included Asian American women. Often, when white writers mix autobiography with the essayistic, the historical and the fictionalized, they’re lauded for their formal risks and genre innovations—and yet when writers of color do the same, they rarely receive the same critical engagement. I often think of the fact that the term “autofiction,” usually thrown around to describe experimental white writers, was coined in 1977–but Maxine Hong Kingston published her hybrid masterpiece The Woman Warrior in 1976.

Dictee was one of the first books that taught me the transformative power that art could have on the material of a life—that conceptual art wasn’t only populated by urban white folks, and lives like Cha’s or mine or my mother’s could make a strange and wild home there, too. That the prevailing wisdom of the time, which was that any whiff of the “ethnic” in art necessarily diminished the art, banished it to a lesser kingdom (reduced it to immigrant art, WOC art, sentimental family epic art), was racist gatekeeping nonsense. That a writer’s formal choices could be packed with emotional and historical density; that the words we use (or can’t use) are heavy. That sometimes it’s possible to carry that weight through to page—but sometimes it isn’t, and all we carry through is the impossibility, and that impossibility is worthy of our art, too. Dictee also taught me that you can write yourself a canon, as Cha does throughout the book, situating her speaker in a long line of women throughout history (the Korean revolutionary Yu Gwan-Sun, Joan of Arc, Cha’s own mother)—and that in writing yourself a canon, you can write yourself a history.

Cha was raped and murdered by serial rapist Joey Sanza in New York in 1982, a week after Dictee was published. When I first read Dictee, I didn’t know of the circumstances of her death. When I read Dictee as an adult (my second first time), I did. Jia Tolentino has written poignantly of the constant low-grade anxiety about how media coverage of the #MeToo movement—my own work included—had a way of reducing women to the abuses they’d experienced, much like sexual assault itself can cause women to feel reduced to their trauma. Such coverage can narrow a woman’s identity to her body, and what other people had wanted from it. It spotlights isolated moments of unwanted sexual contact, acts that tend to be predictable and formulaic in ways that the rest of our lives are not. I won’t say that the knowledge of Cha’s death single-handedly altered my reading of her work. But I also can’t say that the facts of her death don’t shake me to my core. #MeToo and the ongoing fight against sexual assault and femicide continues to be generation-defining, and most days, I hope that the descendants of Theresa Cha, myself included, go on to make work as heavy, as daring, as singular, as Dictee. But I also just wish Cha was here to make that work herself.

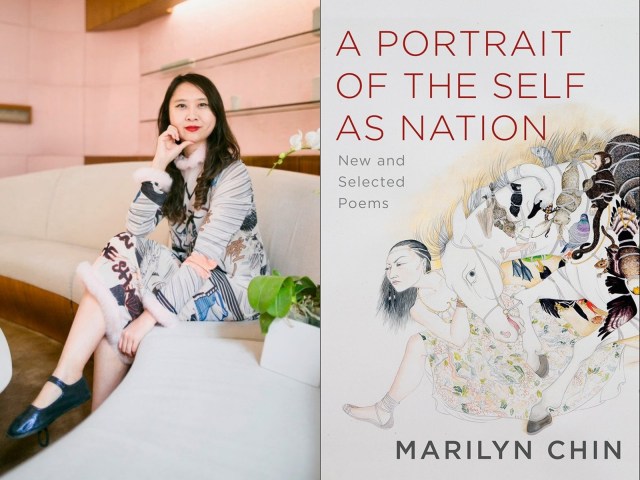

Sally Wen Mao: “Portrait of the Self as a Nation, 1990-1991” by Marilyn Chin

I’m here to talk about the first poem I’ve read by an Asian American woman poet, and that’s Marilyn Chin. She is an OG for a reason – her poetics never delicate, never polite or apologetic—her presence enduring, refusing to quit, refusing to be quiet. Marilyn Chin’s poems command the room—they can make you bowl over in laughter and bawl at the same time. I remember finding her name for the first time in my university library—in a Pushcart anthology. It was a love poem called “Portrait of the Self as a Nation, 1990-1991.” From this poem, a love poem, a celebration of the self, and also an elegy, came a stream of the most perfect unapologetic lines: “They convince us, yes,/our chastity will save the nation—Oh mothers,/all your sweet epithets didn’t make us wise!”

Marilyn Chin taught me how to write a love poem to the self. Not only was she the author of this poem, but her name was in the poem itself—significant, to declare so lovingly a name. And coincidentally, this poem has re-emerged in her new book, Portrait of the Self as a Nation, released in 2018 from W.W. Norton as Marilyn Chin’s new and selected works.

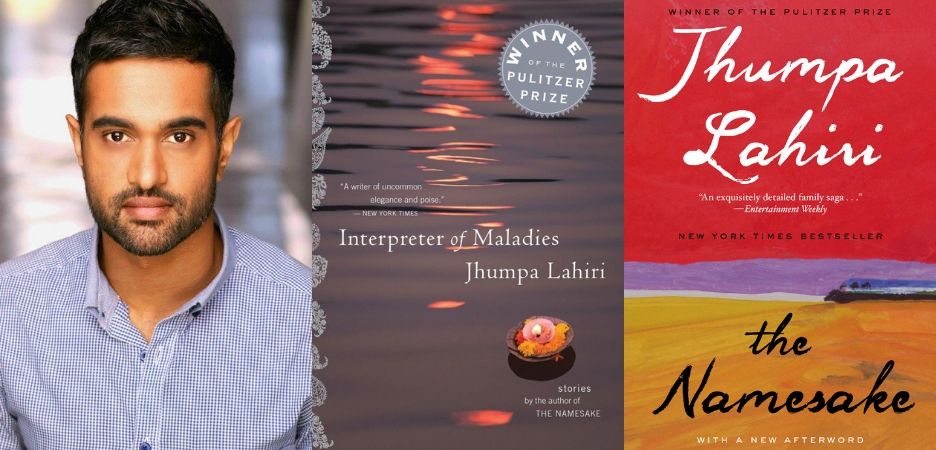

Neel Patel: Interpreter of Maladies and The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri

I was in college the first time I read Jhumpa Lahiri’s work. A friend recommended her, and, during a particularly cold winter afternoon, I decided to dig in. What struck me most was the clarity of Lahiri’s prose, like a spotless window, through which entire worlds could be seen. Before reading Interpreter of Maladies and The Namesake, I had never encountered the work of an Indian American writer before. Her characters were instantly familiar, her stories like pages from my life. I devoured both books in a matter of days. I still read Jhumpa Lahiri’s work today. She made writing seem possible for me. Like my parents, who crossed oceans to build a life for me in this country, Lahiri paved the way.

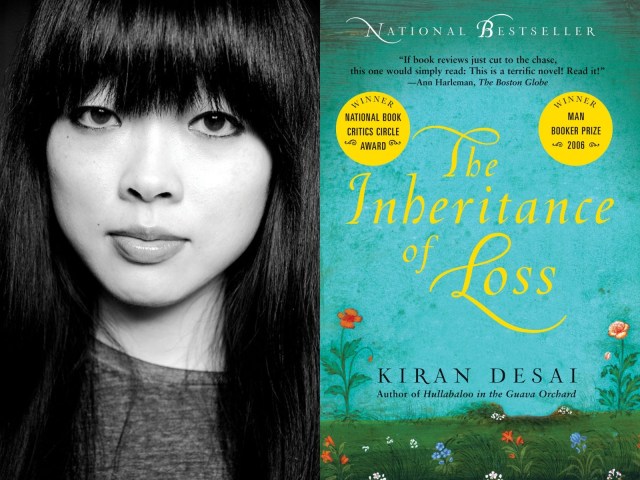

Tracy O’Neill: The Inheritance of Loss by Kiran Desai

I was a nineteen-year-old studying in Rome when I read the novel The Inheritance of Loss by Kiran Desai. Since my adoption from South Korea as a baby, I’d not once left the United States, most of the books I’d read were set in places I had not travelled, and I had never read a book by an author born in Asia and living in the United States like me. It seemed, at the time, that my relationship to geography was shifting. Sai, one of the characters in the book, is reading when the novel begins. Her world then is plush with mist, but she is paging through a National Geographic, in search of the world beyond her frame. “No human had ever seen an adult giant squid alive,” Desai writes, “and though they had eyes as big as apples to scope the dark of the ocean, theirs was a solitude so profound they might never encounter another of their tribe. The melancholy of this situation washed over Sai.” To me, there was a sense that the book, which adopted such graceful rhythms as it alternated between the perspectives of characters across the world from each other, was like tightening the ocean, bringing closer lives I’d never seen in literature.

Đỗ Nguyên Mai: Rice Without Rain by Minfong Ho

One of the first books I read that was by an Asian American author was Rice without Rain by Minfong Ho. The book follows seventeen-year-old Jinda, who lives with her family in rural Thailand, a place where rice farming sustains nearly everyone’s lives. However, as the book’s title suggests, the rice fields have lacked rain, and outsiders begin to plant the seeds of revolution within the minds of young people like Jinda. Although Rice without Rain is a work of fiction, the book reminded me of my grandmother’s rice fields in rural Vietnam, and the contrasts between urban students and rural families that Ho highlights were incredibly similar to the urban-rural divides between my own family members. Most importantly, Ho’s work demonstrated that my family’s story as Vietnamese Americans and as people from rural Southeast Asia was worth sharing. Ultimately, reading Rice without Rain inspired me to be less timid about writing about my family’s experiences.

Karissa Chen: In the Year of the Boar and Jackie Robinson by Bette Bao Lord

In fifth grade, my class read Bette Bao Lord’s In the Year of the Boar and Jackie Robinson. While I can’t be totally certain that this was the first book by an Asian American author I’d ever read, it’s the first one that made an impression on me. Telling the story of Shirley Temple Wong, a young girl who moves from China to the United States the same year that Jackie Robinson joins the Brooklyn Dodgers, this book was the first I’d ever been assigned for homework that featured someone who looked like me. Though I was American-born Chinese, and the protagonist’s overt struggle to understand American culture didn’t completely resonate, nevertheless, I think I did relate to the challenges of balancing Chinese and American culture, even if I wasn’t self-aware enough at that point to be able to verbalize it yet. I also remember feeling a surge of pride that I had an “insider” knowledge of the culture Shirley came from, one that no one else in my class had access to. In class, my (white) teacher wanted to teach the class about Chinese culture, and I remember being proud that I could go up to the board and show everyone how to write the characters for “teacher” and “school.” I don’t know that there were a lot of opportunities for me to feel proud of being culturally different when I was young (I have a lot of memories of being made fun of for stinky food and being embarrassed by my Chinese middle name), but here was a distinct memory of one.

Looking back now, I also realize that this book was one of the first to illustrate for me the notion that Chinese Americans share struggles with other marginalized communities, particularly other communities of color. In the book, Shirley feels a kinship with Jackie Robinson, her idol, because she sees that he, too, is navigating a white space as an outsider. I don’t know that I ever thought, until that point, that the Civil Rights Movement and discourse around Black Americans had anything to do with me — but Lord’s book drew a parallel in which I could view that history through a non-white lens, one more informed by own personal feelings of difference, assimilation, marginalization, and identity as a Chinese American girl. Again, I don’t know that I knew enough to understand this is what the book was doing for me, but even to this day, I can’t separate the story of Jackie Robinson from my first exposure to it, through this book, and Shirley’s understanding of it.

As I grew into a teenager, Lord remained, along with Amy Tan, two of the only Asian American — and Chinese American — writers on my periphery, and I read her adult novels with the same attention I had with her middle grade book. While I always had the sense that her books — about a China I had no personal knowledge of— weren’t entirely about me, I was grateful for their existence. They were proof that a little Chinese American girl could grow up to publish a book about someone much like herself. Even more importantly, they were proof that who I was and where my family came from mattered in the canon of American literature.

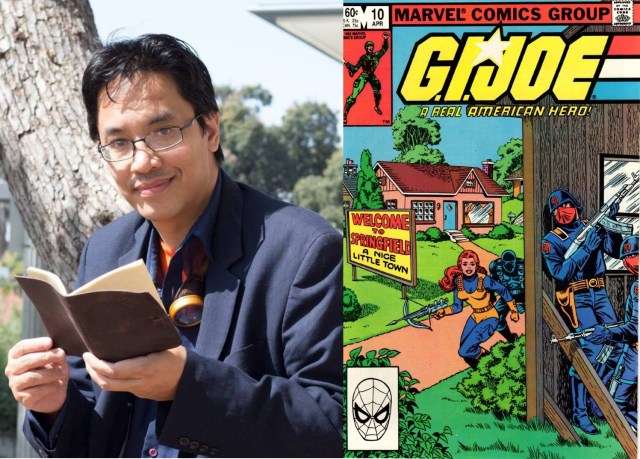

Bryan Thao Worra: G.I. Joe comics by Larry Hama

Growing up in the 1980s in the US in the aftermath of the Secret War for Laos, there weren’t many books about the Asian American experience, especially in my corner of Michigan. At that time figures like Amy Tan, Maxine Hong Kingston, and Asian American poets weren’t a part of K-12 reading assignments. My first exposure to Asian American writers was through escapist literature – most notably, Japanese American writer Larry Hama, who wrote the stories for the modern incarnation of G.I. Joe.

Like Filipino American science fiction writer Robert Aspirin, Hama didn’t exactly make it easy for people at the time to guess he was Japanese American. But today, with a thoughtful re-reading, you can see at his best, he often offered readers a tantalizing glimpse into the Asian American experience, with a look at complex conflicts of loyalty, class and power, our global roles, and the people caught in between the schemes of the powerful. I found Hama’s approach fascinatingly subversive as he created complex villains who were not a faceless Yellow Peril, ethnic terrorist hordes or drug dealers so common for the 1980s. Instead, the main villains Hama warned us to beware of were uber-capitalists and would-be technocrats driven by greed, ruthlessness and ambition. This was a remarkably bold topic compared to his contemporaries. His approach to creating a widely-read Asian American literature informed much of my own as a poet and writer over the decades, and I hope in time people appreciate what he did.

As a footnote, Hama’s G.I. Joe #10 featured a throwaway line during the interrogation of a captured member of the G.I. Joe team that reveals his secret missions in “Berlin, Cuba, Cypress, Chile, Laos, and Cambodia…” For young 10-year old me, it was the first time I honestly felt seen among all of the books and films, TV shows and games of the day.

Chaya Bhuvaneswar: The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston

It was the ninth grade. We had a teacher, a new one, who was dreamy and knew it. There were stories, too, that he was not only too blunt, but dated girls. He didn’t try to date me. Yet he was blunt to the point where it hurt, saying that my writing was good only when I didn’t “over-explain.” I grew self-conscious, quiet in his class, but the books he assigned nearly made up for it. Of course there was The Catcher in the Rye, which seemed to be describing his fellow white prep school brothers. But then there was also The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston, and reading that book made me a writer. Reading her, I wrote my first poem about an early and certain memory in nursery school when a little white boy I’d liked had mocked me for the brownness of my hands, jeering “Chaya can’t wash the brown dirt from her hands,” mispronouncing my name. Because of the book and the way it opened up secrets, I found myself alone at night typing – a process that has never stopped, transforming the “centuries of insults carved into my skin” into a song. My own.

Patrick Rosal: Oral Storytelling

If I told you my cousin Ed, who drives a truck in Atlanta and doesn’t read books but texts me on every January 1—“Happy New Year bro! God Bless!”—would he count as an Asian American writer? When we were drunk one night on my mom’s porch in New Jersey and he told me the story of being back in Balacad, Ilocos Norte, and running out into the woods early in the morning with other children, racing each other to see who could find the most mushrooms just sprung up overnight, was he not, at that exact moment, an Asian American writer? Were we not both descended from the peoples of an archipelago at the edge of the Pacific, colonized by Spain and America? When Edmond tells me that during his early morning foraging he once stopped short the instant he saw the familiar swell of dead leaves on the ground that shouted, “MUSHROOM RIGHT HERE!” and he joyfully plunged both his little hands into the earth to reap it, when he tells me he felt the soggy prize in his fingers before he smelled it, when he tells me that under the mound in the ground was no mushroom at all, when he says, ”It was a pile of shit!” for someone had beat him to the spot and unloaded their bowels, covering the stink with mulch, so it looked like a delicious fungus but was really a load of human crap, has he not composed a metaphor for the world to come?

All of my earliest experiences of Asian American literature—all—were oral. The stories emerged from rituals—formal and spontaneous. It meant that I was gathered with others. It meant I had a model not just for storytelling, but for listening and paying attention. Real people. Ordinary people. Complicated people. What I now read and what I make is informed by this rich, vigorous, and disappearing practice. Every Asian American book that I have loved from Bulosan to Hagedorn to Gamalinda has taught me the importance of preserving this. I shit you not.

Editor’s note: This piece originally misidentified Đỗ Nguyên Mai as Mai Der Vang. We apologize for the error