interviews

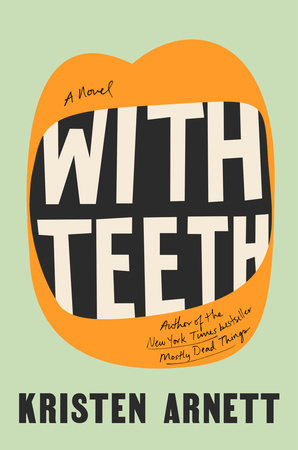

In Kristen Arnett’s “With Teeth,” Being a Queer Mom Is Terrifying

The author on trying to raise a family outside the confines of heteronormativity

You might know her from her uproariously funny Twitter account or her New York Times-bestselling debut novel, Mostly Dead Things, or maybe you’re just being introduced to the former librarian-turned-literary-superstar/Florida brand ambassador now. For fans of Kristen Arnett, the anticipated wait for her next book is over. With Teeth is out just in time for how it’s meant to be read: outside and preferably with a glass of two-for-eight dollar red wine from 7-Eleven in hand—an homage to its author.

Despite how much she loves him, Sammie Lucas is frightened of her own son. Samson makes little to no effort to reciprocate his mother’s efforts to bond with him, leading Sammie to question her own maternal instincts all while taking on all the responsibilities of the household as her wife, Monika, continues to invest the majority of her time and attention into work. As her resentment towards Monika builds and Samson’s hostility grows up alongside him, Sammie is forced to reckon—with herself.

As she struggles to reconcile her past as a carefree young queer woman living her life from one night out to the next with her role now as wife and mother, she is forced to consider the possibility that the doubts she possesses and the questions she asks may ultimately lead her down a path as winding as the Florida roads she drives along.

Embedded with Arnett’s unmistakable brand of humor and permeating with a fresh display of vulnerability, With Teeth is a gift with a heart as big as its author’s.

Greg Mania: I love that we’ve started to develop a pattern of interviewing each other every time one of us has a book out; I hope we continue doing this well into the afterlife.

This book is, in some ways, a departure from your last. Your voice is still present, as is your sense of humor. But I feel like you’re embracing complexity more here, taking a beat to sit in discomfort a bit longer. What was that like for you?

Kristen Arnett: Honestly, it was… difficult AND fun? Some of the difficulty came from the natural unease of writing a character that so often self-sabotages. Going through that first draft, it was like, “God, this asshole” sometimes whenever Sammie would make a choice that seemed terrible. But that’s just her character! And also, I loved it? So much of humor is subjective. I think you and I have talked about that before, but I am obsessed with trying out different types of comedy, purely from a stylistic point of view.

For Mostly Dead Things, it was hilarious to watch Jessa be the straight man (pun intended), the person who never got the joke while everyone laughed around her, but for With Teeth, I had the most fun putting everyone into extremely uncomfortable situations! Like, I thought, How much discomfort can I put into a scene and still find it hilarious? And that was ridiculously funny to me, to make these characters deeply ill at ease, to make them press through embarrassing and awkward situations—deeply HUMAN situations. Because god knows we’ve all been there!

GM: You offer a masterclass in how to write queerness—or any identity marker for that matter—without it serving as the facilitator of plot in both of your books. With Teeth is about queer relationships and queer parenthood, but at the end of the day, it’s about relationships and parenthood. Queerness is something that’s just there; it’s not looming nor is it an impetus of any kind. What made you want to explore parenthood through the lens of queerness?

KA: It felt really important to me to think about queerness here in terms of community; the having of a community, sure, but also the lack of one. There’s this way in which queerness in Central Florida is there, but not actually represented. People move from all over the world to work at our theme parks, and many of those people are gay, but there isn’t a corresponding representation of queer-servicing spaces to accommodate them. Like, hardly anything. And the spaces we do have are very much places for single, young people: bars and clubs, that kind of thing. There’s this unspoken stuff that happens in queer community.

I’ve noticed in Central Florida when once you’ve leaned into marriage and kids, you no longer fit into what is available to you in terms of queer spaces.

I’ve noticed in Central Florida when once you’ve leaned into marriage and kids, you no longer fit into what is available to you in terms of queer spaces. Like, there are no mommy groups or anything, there aren’t places to go where you see yourself reflected back at you. And if there are some, there aren’t very many. We’re a red state. So then it becomes trying to fit into some kind of heteronormative roles that don’t fit with queerness, all for the sake of raising a child. It would be devastating and so goddamn hard, you know? I wanted to really lean into this stuff, because what if, hear me out, the person being shoved into this role (someone who’s constantly under scrutiny, someone who has to be perfect at it, even more so than a heterosexual parent), just really fucking sucks at being a mom? That, to me, felt extremely important to write about.

GM: How much do you think that the pressure Sammie feels—always caught in the crosshairs of those who doubt two queer parents, specifically two women, can successfully raise a boy—accounts for her missteps in motherhood?

KA: I think that would have to be part of it, for sure, but I think it’s more complicated than that. The fact that Sammie feels these pressures in her life that are put on her with regard to motherhood and queerness—very real pressures, absolutely—means that she can kind of push all of her insecurities onto that. So there are ways in which she very likely doesn’t take ownership for the ways in which she is complicit in her own bad choices (selfishness, etc.) because she’s able to fob it all off on these pressures. It’s not my fault, it’s society—that kind of thing. In reality, it’s society AND Sammie. It’s both things. I think that’s why Sammie feels so deeply real and very human to me. She is messy and she kind of understands that, but she’s also a person who doesn’t want to be judged for it (I mean, who does), but she also doesn’t want to deal with her wrongness, either, so she makes up a lot of excuses.

GM: I also appreciate that queer trauma isn’t at the forefront—Sammie’s parents’ rejection of her is brought up for context, but it doesn’t overstay its welcome.

KA: Right, exactly. That is something that’s there, of course, something that’s going to inform her character and the choices she makes, but it’s not going to be the overarching theme of her life or her story. Queer people have these issues all the time, right? It’s the stuff that’s contained inside of us, to a degree, but it’s not the totality of who we are.

GM: I’m going to volley back a question you asked me, one that stayed with me long after I answered you: your relationship with your parents—and your subsequent estrangement from them—has shaped so much of your work. How do you see it shaping With Teeth and also shaping future work?

KA: I mean, I think those past relationships absolutely mark who we are, because they have a say in who we’ve been and where we’re headed, you know? I think that it has to sit there a little in how I’m thinking about this character who is also estranged from her parents, because I think it would also inform how she thinks about her relationship with her own kid. I know that it makes me think a lot about the role of family in my own fiction—the dynamics of how specific relationships function—because that is a big part of my own life, especially as a queer person. I mean, it makes me consider all the ways that we define family. Blood isn’t always who our closest family is, not when you’re queer and you have the freedom to make up your own household. Intimacy—romantic or platonic—is a big part of how I consider who makes up my world. I want to write that into my fiction because my fiction is queer, too.

GM: Are there any other texts that have recently piqued your interest in terms of their exploration of queerness? If so, which ones?

KA: Oh, wow, this is a great question because I honestly feel like there are so many. Every day there are more and more extremely queer, extremely great books being published and it just makes writing and reading feel incredible! I have to say that Torrey Peter’s recent book, Detransition, Baby, is just magnificent, and discusses so much about queer parenthood. Just phenomenal. Memorial by Bryan Washington is so queer and also dissects place and relationships. Pizza Girl by Jean Kyoung Frazier is so extremely queer and so messy and interesting, unpacking queerness and motherhood and class at the same time, which is just wildly impressive. Every day there is just new gay fiction and I am so in love with all of it!

GM: Since Sammie is the narrator, we get a front-row seat to her internal life. But, as a reader, I sense a rich complexity in her wife, Monika. What made you want to write the book (mostly) from Sammie’s perspective, as opposed to dividing it between Sammie, Monika, and their son, Samson?

Blood isn’t always who our closest family is, not when you’re queer and you have the freedom to make up your own household.

KA: That was very purposeful on my part, because it relates back to my very firmly held opinion that everyone in a household is an unreliable narrator. I wanted to be pretty close on Sammie, a woman who is queer and a mother and navigating those identities, and see how much of her story I could tell without needing another voice to take over and give it credibility or contradict her, because I think in our own minds inside a household, we are the main characters. I also wanted there to be a real sense of claustrophobia on Sammie’s part, because her life is running a household, but it is essentially run entirely inside that household. She moves from the house, to the car, to wherever she is dropping off her kid, and then back again. Her world gradually narrows, this feeling of being stifled, confined—I wanted that there, absolutely. I think it was important for that voice to belong to Sammie alone. Plus, I think it really adds an “Oh, fuck” quality to things once you realize how little she’s able to see things in terms of everyone else’s perspective.

GM: Something I’ve been thinking and talking about a lot lately is the complexity of grief, especially ever since reading Tomboyland by Melissa Faliveno. She writes about the nuance of grief, how it can appear in many shapes and forms, and considers expanding our definition of it. To me, it seems as though Sammie is grieving what once was—and not just her marriage and the baby she lost—but also who she used to be: a party-goer, care-free, able to move through life with an almost reckless abandon. Was grief an emotion you considered when writing about Sammie reflecting on her life before meeting Monika?

KA: Oh, absolutely, yes! Grief is one of those things that takes so many shapes, a million forms. For Sammie, I think it’s perfectly reasonable that grief would be stuffed inside of a lot of other things (a ravioli of feelings, if you will). I also think that Sammie is a person who probably didn’t realize that grief was what she was feeling for a long, long time. That happens, too, I think—this way in which we compartmentalize feelings that we don’t like, refusing to allow them air, never really understanding what it is we’re actually feeling because we don’t allow ourselves any time to examine it. People are so messy, I fucking love it.

GM: Now to the more-serious questions: there are still nods to 7-Eleven in this book. Do you still get the usual (Steel Reserve and Yosemite Road two-for-eight dollar red wine)?

KA: Of course I do! God, it’s such a great value. I have a four-pack of Steel Reserve tallboys in my fridge right now, actually! Might as well crack one open and drink it, why not!

GM: Florida reprises its role as a character in and of itself in this book. Do you think that the way you write and think about Florida has changed since your first book?

KA: I really think so, yes! And that makes sense to me, because I think about Florida like I’d think about another person, and people are changing all the time. They change, but so do I, everyone does. And that means our relationships to each other are changing, too. So my relationship with Florida is still there, still potent, still so strong—just ever evolving, turning into something different every day.

GM: What’s it like now?

KA: I think it’s cycling back to a place of freshness again. And by that, I mean I feel like I’m starting to see it through new eyes. Like, romantically. Like Florida and I have been in a long marriage and we kind of sometimes take each other for granted, but right now we’re rekindling things. There’s a spark. Part of that definitely comes from this past year of pandemic, being away from home in the desert half that time at my fellowship. It made me miss home so fiercely. I just couldn’t wait to be back again, to feel that warm, sticky, humid embrace. And now that I’m down in Miami, I’m getting to know a whole new side of Florida. It all feels really new. I feel very much in love.