interviews

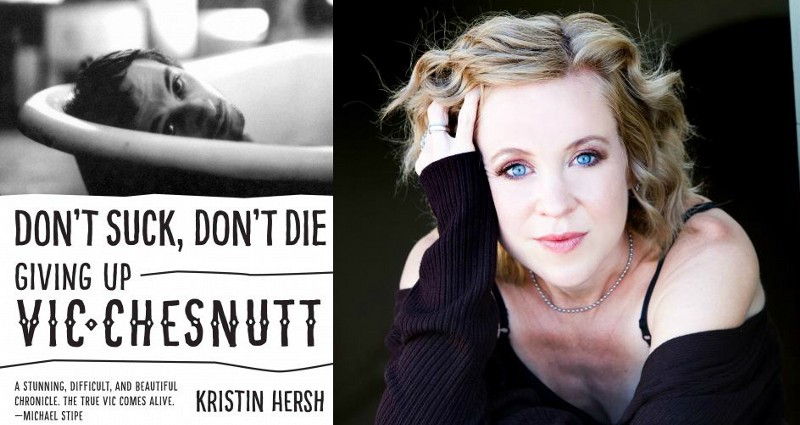

Writing Raw: A Conversation With Kristin Hersh, Author Of “Don’t Suck, Don’t Die: Giving Up Vic Chesnutt”

Vic Chesnutt had this thing he’d do when he was ready to go on stage- he’d crook his arms and flap them like they were wings. Vic said the flapping made him lighter, like a bird, and whoever was nearby would lift his wheelchair. Once Vic assumed his rightful place, either he’d transform, or you would, as he’d carry you to the highest highs, or the lowest lows, transporting you out of this realm, all in the space of a song.

2009, the year Vic died, was the first year I felt old. I wasn’t alone. It was a feeling shared by all who loved him. I felt old partly because I knew I’d never see Vic play live again, partly because I was afraid people would forget Vic’s way with words–Wave Books’ Matthew Zapruder once described Vic to me as “the poet’s musician”–partly because I was afraid people wouldn’t remember Vic’s tenacity. Vic managed to play and tour, even though a car accident at eighteen had left him a quadraplegic. But now that singer Kristin Hersh has her memoir about her friendship with Vic, Don’t Suck, Don’t Die: Giving Up Vic Chesnutt (University of Texas Press 2015), already being heralded by NPR as “not only one of the best books of the year, (but) one of the most beautiful rock memoirs ever written,” I feel like I can breathe more freely.

Hersh is the founding member of the bands Throwing Muses and 50 Foot Wave, and the author of the critically acclaimed memoir Rat Girl. We met in Vic’s adopted hometown, Athens, Georgia, on the opening night of her book tour, before a reading and a performance at the 40 Watt Club. We discussed writing raw, how writing sometimes takes on a life of its own, and why keeping Vic’s memory alive is necessary.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: How did you come to write this memoir?

Kristin Hersh: University of Texas has a series of musicians-on-musicians and they approached me when they found out I knew Vic. I told them I have no right to write any kind of biography–all I can do is present a series of fuzzy memories from ten years ago. And if you’re okay with that and the type of prose poetry writing I do, it’s more like painting than communicating, then I’ll try. It took them a long time to talk me into it, and mostly that’s because I wasn’t qualified. And that’s why it’s a memoir, not a biography–it’s all my little memories of conversations and moments for me. Those are the impressions I carry around of Vic and his wife Tina, just photograph after photograph after photograph until you get the essential form. I remember conversations we had not word for word, just the way we talked. It’s sort of dreamlike and when you put yourself back in time that way you become nonjudgmental. This was actually a nice time tripping exercise.

DS: I was curious about that aspect of it. Was it like channeling?

It’s not really a normal book. I’m realizing that. It doesn’t impart much information. It’s more like a dream.

KH: It was raw. I started the outline when my life was as it always had been, and as I wrote the book my life began to fall apart. My husband left me. I’ve gone from a mother and a family of six to a single mother of one child and I’m sort of like Vic used to say–I feel like a ghost. These memories were stronger than my life, and the pain in my life helped the process become something that was not clever at all, that was just peeling off my skin, and that suits Vic, because that’s what he did. He was more honest than maybe he should’ve been and so the book is just a picture of that. It’s not really a normal book. I’m realizing that. It doesn’t impart much information. It’s more like a dream.

DS: But a lot of times that’s what’s good about books–if they’re not normal, right?

KH: I guess that’s the only other place to go. If you want a kind of reality to exist you have to go to a dream. I don’t really believe in imagination like I don’t believe in the creative personality. I think humanity is what we are all at, it’s at our core, and it’s what we’re aiming for, so if you can bring about humanity you have to do it in a very ham-fisted way, just never be clever. Never be in charge, at least that’s my m.o. It’s my m.o. for music and for writing it’s the same thing. It’s rhythm and melody and raw. That’s really all I’ve got going for me.

DS: Can you elaborate on that–about Vic being very raw and more honest than most people?

He had an interesting kind of dirty purity and that’s not a bad way to grasp humanity–that may be all we have going for us.

KH: Yea, he was more honest than most people in an almost knee-jerk way, and yet he said he lied. And I think his definition of lie was more, ‘I have colored this in such a way as to make you understand its emotional impact.’…And that’s how he knew to tell the truth. It’s an odd way to go about it. It’s very poetic. A little confusing. Tina and I have been trying to sort out what was told to me and what was actually true but at the end of it the impression of Vic remains the same. He had an interesting kind of dirty purity and that’s not a bad way to grasp humanity–that may be all we have going for us. You gotta have the dirty and you gotta have the human and everything else is just the little differences that make up the day to day minutiae. Vic was more about the essential.

DS: With this process with writing a memoir about somebody else, how did that differ from Rat Girl?

KH: That was taken directly from old diaries. My notes for this book were tour calendars and song notebooks so they were snatches at best. Each scene was just a combination of a bunch of memories put together. But of course a musician’s life is so repetitive. We had the same conversations over and over again and the same experiences over and over again and all I could do was present what they were like.

DS: You were able to like capture the whole mundanity of touring. All the waiting.

KH: So you either stare at each other, or you have a heartfelt conversation, or you bullshit. We did all of it. There’s no better way to communicate with someone–staring, real-ing, and bullshit.

DS: I loved what you wrote about the period where you weren’t talking to Vic, and how you listened to his music to get close to him. Because you had never really listened to his albums before. It reminded me of a conversation I had with Vic. We were at a Jonathan Richman show and I asked him what his favorite Jonathan albums were. And he said, “I’d rather see Jonathan play live than listen to his albums any day.”And I was said, “But Vic, not everybody can do that!”

KH: Yea, and we sat on stage a few feet apart so I was able to watch this bizarre transformation he did on stage–I’m not sure the audience could even see. He seemed to age and de-age and morph. It was a fascinating process. and to watch his fluid timing, which he says was the result of having the use of only two fingers, but it was so beautiful there was no way he would have done it otherwise. I was envious of it and I couldn’t mimic it with my math rock bands–it was moving.

He also introduced poetry to me. My lyrics had always been words that didn’t get caught in my throat, phonetic melody. You know you’re lying if it gets stuck in your throat. I was just telling the truth. And what he went for was a softer beauty that actually has more resonance and texture than the violence I think I was playing for so many years. I didn’t change you know.

I’ve lost so many people in my life and he’s the only one where I think, what, dead forever?

To be in a room while he sang love songs to Tina and while I sang love songs to Billy and we laughed and welled up–like Tina said today, it was just a good time. She’s gotten to the point where that makes her happy. For me, I feel like a walking ghost, like my life happened but for some reason I’m still here. I gotta get to where she is and I guess that means having a future. It’s hard when the person you’re talking about does not. Vic has no future. That’s so confusing. I’ve lost so many people in my life and he’s the only one where I think, what, dead forever?

DS: You wrote most of this in the second person. How did you choose that method?

KH: A British newspaper, the Guardian, asked me to write a letter to someone, it’s a series they do, and I wrote to Vic. And I just used that technique. When somebody goes, there’s a lot that’s left unsaid, even if it’s: “wasn’t it amazing when we laid down by the lake and listened to our new songs?” I didn’t say that so it gave me a chance to say those things. I just let it fly, and even the iterations that happened over the last year and a half were just filling in the impressionistic coloration, for lack of a better term.

And the book got darker as my life got darker, and I apologize for that, because you probably shouldn’t let your emotional state color your work. I’ve found that in songs, but this I couldn’t help, two sad endings at once.

DS: Because you are sideways writing about the loss of your husband.

The book starts with balls and ends with tears. It’s a bad direction to go.

KH: I had seen this book as a black and white movie about two couples where three have something in common and the others have something in common and there are machinations between them, like a play almost, in black and white. It was all so sweet until things started to line up and they lined up too cruelly. By the end it’s a particularly lonely book and when it starts out, there’s just so much good work to do. I really felt like we needed to be here for a reason, all four of us, and now I just feel like a wisp of smoke. It’s hard to imagine ever having balls. The book starts with balls and ends with tears. It’s a bad direction to go.

DS: But even though it’s sad, you handle it beautifully.

KH: Well, it’s a love letter to Billy and Tina and Vic. I’m the last one still living our life. And the fact that Vic and I thought our brokenness would be fixed by these amazing healthy people who somehow let our pain resonate with them must’ve been why we were such happy people. People talk about us as if we were depressives. We’d had dark moments. We knew pain. But we were happy, laughing people, and we married these happy, laughing spouses who knew pain, but were for some reason weren’t broken. We chose the perfect mates for ourselves, and that’s what the love letter is. Thank you to Vic for resonating with me and thank you to our spouses for keeping us around as long as they did.