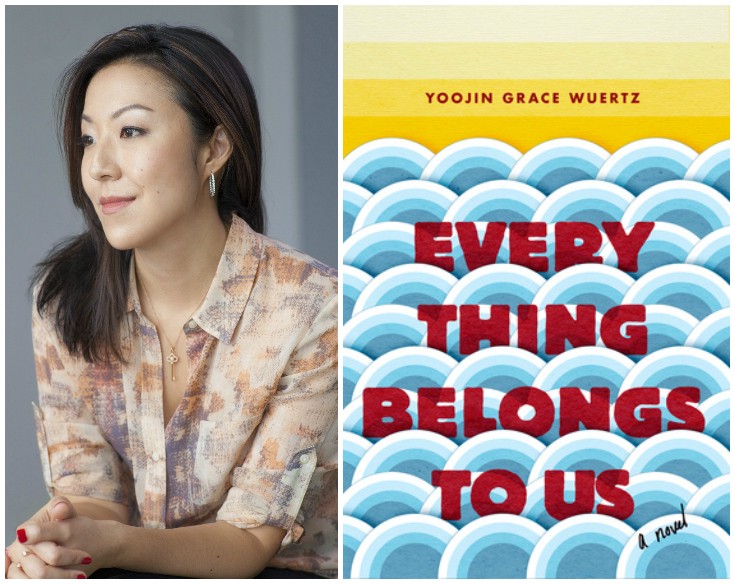

Interviews

Yoojin Grace Wuertz Takes On a Turbulent Moment in South Korean History

The author of ‘Everything Belongs To Us’ discusses activism in a time of dictatorship, the drive to succeed and her debut novel

In her debut novel Everything Belongs To Us, Yoojin Grace Wuertz transports readers back to 1978, to Seoul National University in South Korea. Four students — Jisun, Namin, Sunam, and Juno — struggle to succeed financially and socially during the final years of a repressive regime that also incited an economic transformation in the country. Jisun, a tycoon’s daughter, shuns her privilege to become an underground labor activist. Namin, her childhood best friend, lifts her family out of poverty by soaring to the top of the class. Juno will stop at nothing to get it all, including top rank in the university’s prestigious social club, “the Circle.” And Sunam, lover and villain, drives a wedge between the women, changing their lives forever.

Born in Seoul, Wuertz immigrated to the US when she was six. I met her at Tin House Writer’s Workshop in 2012, where I first witnessed the compassion she transmits from her heart to the page. She is brilliant, poised and determined, and while her prose is keen and tidy, the intimate relationships she creates in her stories are messy enough to be true. She currently lives with her husband and son in New Jersey, which is where she was when I phoned her to discuss writing historical fiction, listening to our elders, enduring an authoritarian leader, and Everything Belongs To Us.

Andrea Arnold: South Korean history hasn’t been widely covered by American novelists. Why did you choose to set Everything Belongs To Us in 1978?

Yoojin Grace Wuertz: My parents were college students in Seoul in the 1970s and I became fascinated with the stories my dad would tell me about that period. It was a very dynamic, volatile time because the economy was growing at an unprecedented rate under a repressive and authoritarian government. Park Chung Hee was President, and I chose to set the novel in 1978 because many factions in the country — student and labor activists particularly — were rising up in dissent during that time. [The President] was assassinated in 1979, three months before I was born. As an immigrant kid, I noticed cultural differences between Korea and the U.S., of course, but I didn’t understand the political differences. It started as an intellectual interest but ended up being personally meaningful because it helped put my own history and identity into larger context.

AA: Financial success is everything to everyone in the novel except for Jisun. After we leave these students, an economic transformation occurs in South Korea. What was life like for South Koreans before and after the economic transformation?

YGW: My parents were born in 1953, 1954 at the end of the Korean War. For that generation, the post-war generation, they witnessed several generations’ worth of economic progress compressed into thirty years. In 1953, Korea was among the most impoverished countries in the world with something like $50 GDP per capita, which is really hard to imagine now, in 2017, because South Korea is a major world economy and companies like Samsung and Hyundai are household names. But that shift happened during my parents’ lifetime and during the lifetime of the characters in this novel. And it happened because of the Park administration, which blatantly pursued development at the cost of democracy and human rights. For that reason, Park Chung Hee is a very controversial figure: revered by the older, more conservative generation and criticized by progressives. His daughter, Park Geun-hye, who was impeached from the Presidency last December, has had a similarly problematic legacy.

AA: Jisun is an underground labor activist, although she is also a privileged college student whose father is very wealthy. She is full of contradictions. Who is Jisun?

YGW: I wanted her to have a passion that was counter to her birth and to her grooming. I modeled her father after the authoritarian figures in Korean history. Very successful and nation-minded but brutal. He had a plan for his daughter, and she rebelled against it because she had different ideas for herself and what she considered noble and what she wanted for her future. Jisun has that financial success that was so highly desired by many people in the country, but what she wanted was freedom, democracy and personal agency, which is what she didn’t have in her life.

AA: She falls for a Methodist missionary named Peter. I don’t want to give spoiler alerts, but can you tell me about missionaries and why they were allowed to be in Korea spreading gospel during Park’s regime?

YGW: Christian missionaries have a centuries-long history in Korea, but especially after the war they were instrumental because they brought aid in addition to religion. American missionaries set up universities and supported other educational and social efforts. The government did not oppose American missionaries in the ’50s and ’60s. But in the ’70s when the missionaries became supportive of labor protest and antigovernment and pro-democracy movements with the rise of Minjung theology, which is a Korean social justice theology comparable to Latin American liberation theology, then the government started to feel antagonistic toward US missionaries and US groups. There was a tense balance, because the United States is one of South Korea’s most important allies. The administration had to be very careful not to offend America by kicking out or jailing missionaries, which I reference in the early part of the novel. Peter was protected by his US citizenship.

AA: In many ways the character Namin reminds me of you. She’s brilliant and hard working. Success is her only option. Did you model her character after anyone?

YGW: Thank you, I actually modeled her after my mom! My mom grew up the youngest child in a single parent home because her father passed away when she was an infant. My grandmother, who was an amazing woman, had to raise three kids in an incredibly challenging financial climate. Pretty much everybody was poor, but if your family did not have the primary breadwinner, which would have been the father, you struggled even more. My mom has always been an academic person. She’s always loved reading and studying and learning. The scenes of Namin testing into the most elite middle school in the country, when she was the first one from her working class town to get accepted, that happened to my mom. The town threw her a party! She tested into the top high school and women’s college, Ewha Womans University. She was able to overcome financial and social challenges via education. My father’s stories about the political and cultural climate sparked my interest in researching this time period, but my mom’s personal story became the heart of the book.

AA: Motherhood is another recurring theme in the novel. I’m thinking of the references to ajummas, which is so great because then everyone has a mother even if she’s just the woman next to you on the bus! Can you talk about the changing role of women in 1978 Korea and why motherhood became a focal point of the story?

YGW: Ajumma is a Korean concept I find difficult to translate. I’ve seen it translated as auntie, but that isn’t quite right. Basically, ajumma can refer to any middle-aged or married woman. Sometimes it’s a pejorative word and sometimes it’s an affectionate word, depending on the context. But I guess the translation “auntie” refers to Korea’s communal culture, the idea of communal motherhood and family. When I was growing up all adults were my parents because all adults could tell you what to do. In the novel, I think I chose to create an absence of traditional mothers. Jisun’s mother is dead. Namin’s mother is not supportive of her sister during times of crisis. Her sister, who becomes a mother, has a very conflicted idea of motherhood. Portraying female characters was something that I thought a lot about while writing this novel. I wanted to create women who were anti-convention, who didn’t fall into the expected roles, and so maybe that’s why I created an absence of motherhood. Not because I don’t value motherhood — I’m a new mother myself — but because there is no lack of Korean women being portrayed as mothers and daughters and caregivers. I wanted something else.

There is no lack of Korean women being portrayed as mothers and daughters and caregivers. I wanted something else.

AA: What is Juno’s notion of a “little pond” and where did it come from?

YGW: Korea is a small country geographically. South Korea is the size of Indiana. To the west is China, a huge landmass, culturally influential. On the east side is Japan, maybe not huge in land but historically powerful. Koreans have always thought of themselves as wedged in between giants, which creates a bit of an inferiority complex. In the national mindset is this intense desire to succeed despite its underdog status. Juno, being somebody who is desperate to succeed and project himself as large as possible, says Korea is “a little pond,” and in a little pond you want to learn how to be a big fish, a shark. That way you might get a shot in the ocean.

AA: Games play a big role in your characters’ lives. The university boys play baduk. The Circle hazing involves a sex game. Jisun plays sadistic games with Sunam. Are games important in Korean culture or why are all these games played in the novel?

YGW: Yes. I think games are important in Korean culture. I grew up watching my male relatives play baduk, the Chinese game “Go.” It’s a strategic, cerebral game. Historically only aristocrats were allowed to become educated in Korea. They were called the yangban class, and playing these games of strategy was considered very erudite and marked you as a person of intelligence.

AA: Did your own childhood memories make their way into the novel, and in addition to chatting with your parents what kind of research did you do?

YGW: I read everything I could about the time period, particularly focusing on the protest movements for labor rights and democracy. Contemporary studies with first person accounts were particularly helpful to give me a sense of what people were experiencing at the time. For the Peter character, I read first person accounts of American missionaries who had gone to Korea in the ’60s and ’70s. I did a lot of cultural research talking to my family members about what films they were watching, what music was popular at the time, what they would do for fun, where they would go for dates, and what was normal in terms of friendships and dating and clothing. In terms of my own memories, the novel is set in 1978, two years before I was born, so I would do this thought experiment where I would take my memories of living in Seoul as a child in the early- to mid-’80s and try to slightly rewind in time. If the economy is growing at 7 or 8% as it was during that time, every year makes a difference in terms of standard of living, what people could afford, and also how social norms would track with those economic changes. I would take what I remembered and try to reverse-engineer what that memory might have been a few years earlier.

AA: When you were going through your rewrite you told me about a character you cut from the novel. Now that I read the book I’m curious about the role that other character had. Can you discuss your journey from draft to publication?

YGW: In very early drafts, this novel was about Sunam’s family, his kids. It would’ve been set in the ’90s and ’00s in the United States. What I found while I was writing it was that nobody cared about that story [Laughs]. They were more interested in the flashbacks to Sunam’s youth when he was a college student. So I decided to set the novel in that time period, which actually scared me a lot because I had not set out to write a historical fiction novel. Writing historical fiction scared me because it seemed like a lot of research. [Laughs] And it seemed like I’d have to be an authority on a time period I hadn’t lived through. I wanted to do right by the material because of the people who had lived through it, because I so admired them and the work they had done. Once I started getting into the research and once I started talking to my family members I stopped thinking of it as historical fiction and started thinking of it as how can I tell this story? What would it be like if I was going through this? Also, because my parents and I are culturally very different, they having grown up in Korea during this repressive time and me having grown up in America in a much freer time, we had a pretty tense relationship for many years. Writing this novel actually created so much healing in that relationship, because I was researching this material as a writer who wanted to understand the time period and these characters — not as a daughter who was often quite resentful of the culture. Developing empathy for these characters, who are essentially contemporaries of my parents, helped me to understand where they were coming from in a radical way that I hadn’t been willing to consider before.

AA: Did you start writing Sunam’s story while earning your MFA at NYU?

YGW: Yes. During my first semester at NYU I was still straddling that contemporary family arc. After that first semester I started the draft that became the novel. By the time I graduated, I had half the manuscript. It took me a year after that to finish the manuscript, and I connected with my agent shortly after that.

AA: What was your experience like at NYU? Were there teachers that shaped you or that you emulated?

YGW: I was very intimidated to even apply. My idea of myself as a writer was so fragile because I had already written a failed novel and I wasn’t sure I was supposed to keep going. I would go to MFA open houses, come home and say nope, not this year. It took me seven years to work up the courage to finally send in an application. Thank god I was accepted because I was so afraid I wouldn’t be able to survive the rejection. When I started the program I jumped in with both feet and I loved it! I felt so fortunate to be able to learn from these amazing writers every week.

The professor who helped my writing the most was Aleksandar Hemon, who I had as a second year. He taught a class on editing. I thought editing was just making prettier sentences, and what I learned is that editing is a process where you find what your story is. You find the most interesting way to tell the story, in the most active way possible. Not just tinkering with adjectives, which is something I’d been doing for a long time, trying to hold onto sentences that weren’t helping my story because I’d worked hard on them. I learned it’s okay to write shitty drafts and throw out most of it if it teaches you where the story is for the next draft. He’d say “it’s all shit until it’s not.” If you’ve read him, you know how un-shitty his writing is, and it is very empowering to hear him say “it’s all shitty” before it becomes that remarkably unshitty thing we get to read.

Another professor I learned a lot from was David Lipsky. I was so lucky because I was in both David’s and Sasha’s classes at similar times and they were teaching opposite craft skills that turned out to be complementary. From Sasha, I was learning about structure and plot and organizing story, and what I learned from David was micro word-level editing. He is an obsessive reader. He will ask you to choose that one word in a sentence that makes it great rather than good. Every week he’d come in with a short story that was the best version of itself and say why does this work? Why does this give you a lift? It was a new way of reading and noticing.

AA: What are you working on next?

YGW: You mentioned that you saw the theme of financial success being major in Everything Belongs To Us. I’m writing another book with a theme of class strife. This time it’s set in contemporary America, and it’s a story of a marriage where the two partners are of very different classes, cultures and race. I like working with social differences in intimate relationships.