interviews

The Horror of Being the Other Black Girl in the Workplace

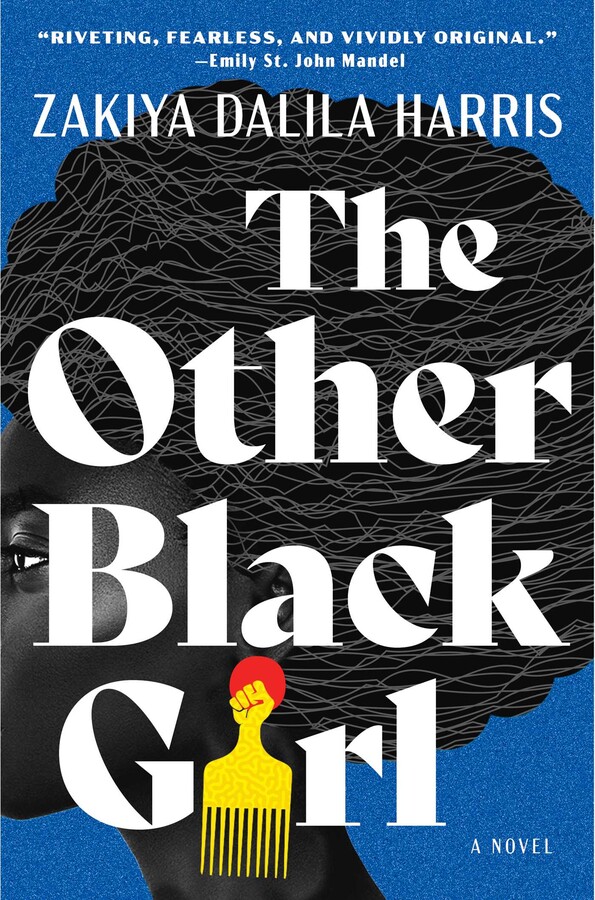

Zakiya Dalila Harris, author of "The Other Black Girl," on what it means when Black labor is overlooked

Publishing is blindingly white—according to the most recent Lee & Low report on publishing diversity, 76% of the industry is white and only 5% of the industry is Black. Zakiya Dalila Harris knows this statistic intimately, she was one of the only Black employees in the editorial department of Knopf/Doubleday.

Her psychological thriller The Other Black Girl confronts the anti-Blackness of the publishing industry, but that examination of Blackness applies to any workplace. The novel follows 26-year-old Nella Rogers, one of the only Black employees at Wagner Books. Until Hazel, a Black woman from Harlem, is hired and starts working in the cubicle next to her. Nella is excited to bond with a fellow Black colleague and ready to make up for lost time. But when she starts getting mysterious notes on her desk that read “LEAVE WAGNER. NOW.”, she realizes that something ominous is lurking in the cubicles of Wagner.

The Other Black Girl takes the ordinary and makes it sinister to interrogate what it means to feel overlooked or threatened in the workplace.

I chatted with Harris about the value of Black labor, allyship, and how privilege plays a role in the risks we do or don’t take.

Arriel Vinson: I want to start by talking about the epigraph, “Black History is Black Horror.” Can you tell me more about this choice? I was really intrigued.

Zakiya Dalila Harris: Tananarive Due has an incredible documentary that came out right around the time I started writing—Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror, about horror films from the 1890s to the present. I have always been a big horror fan. I love all of it. I grew up watching a lot of this stuff.

I was really excited to see a film that critically looked at Black people and their roles in horror throughout time. She touches on how, in some ways, The Creature from the Black Lagoon represented otherness, outsideness, and looks at that as a parallel to how Black people were treated at that time, but even now. It was so inspiring to me because again, being a Black person who loves horror, I happened to see myself in a lot of these movies.

I knew that with this book, pretty much from the beginning, there were going to be some genre elements. I knew Hazel was going to be something other.

AV: You worked as an editorial assistant. What empowered you to write such a critical look at the publishing industry? And did you receive any pushback as you were writing or shopping around?

ZDH: I worked at Knopf and I also worked at Doubleday. I was in a role that no other assistant was in really, because I assisted an editor who acquired for both Doubleday and Knopf, and then one who solely acquired for Knopf and Pantheon.

I started writing this at my desk after running into a Black woman I’d never seen before on my floor and having this moment of, “Oh my God, this is awesome”, but then also, “Wait, why isn’t she excited about seeing me?” We didn’t have any kind of interaction. Looking back, I don’t even know what we would have done. We were in the bathroom, so it was random. But as I went back to my desk, I was like, “Wow, I’m really starved for Black interaction”.

We take risks every day by being ourselves, by going to certain places.

Don’t get me wrong, a lot of times our IT department had people of color, our wonderful mail people were people of color, people working at the front desk were people of color. But it’s not quite the same. There was one other Black person in editorial on my floor, but he was an older Black gentleman, so we both moved through very different worlds.

I was so taken by this interaction that I came up with the idea of two Black women in this white space. Publishing is what I knew, but I thought, “I’m going to change it from publishing at some point, because this might be too much.” But it’s so rich, the way we talk about books, bringing in authors. Those dynamics are nuanced and there are so many things every editorial assistant has to get through. They’re in this prime position to see every possible, wonderful thing about publishing but also everything that is not so wonderful, which of course is a lack of diversity. So I kept going.

I had one moment when I was querying, where an agent kind of surprised me—because I knew who they were and thought, “this person will think it’s necessary,”—and said, “I love this, but I think you should change the publishing element.” I had someone else tell me they didn’t love it. I had a few people say they didn’t love the genre elements. I remember someone telling me, “I’m not sure about it.” I cried. I sobbed for hours like, “No one is going to want this book. No one is going to take this because it is about publishing.”

Thankfully, that wasn’t the norm and a lot of publishing houses were really excited about it, including old coworkers of mine who had really enjoyed it and thought it was eye-opening.

AV: There’s a moment where Nella wonders if she should warn Hazel about how white Wagner is or how anti-Black Wagner is. You wrote this inner debate so well—feeling like we owe other Black people information, but also fearing if we tell them we’re risking our own positions. Why was the theme of risk-taking so important in The Other Black Girl?

ZDH: Nella is inherently not a risk-taker in so many ways. She is, in that she’s still at this publishing house, but even still, she’s kind of coasting. She’s into the diversity meetings [they have], she wants them to happen, but also doesn’t make a stink about it when they don’t. For her, a lot of that comes from her family. She remembers her dad’s anecdotes of working at that place and the moment in Burger King—and I’ve definitely heard similar stories from my family. We have to nod at one another when we are in a room together because who else is going to? We’re looking out for one another.

For Nella, in a way, that is not as much of a risk. She’s also been so starved for more Black friends and having someone at work would be wonderful. She thinks that because both her and Hazel have navigated these white worlds, they are similar in the fact that she’s like, “I would want to know.” Risk-taking is something that we have to do. We take risks every day by being ourselves, by going certain places.

Kendra Rae’s story is also about putting it all out there. Nella doesn’t know everything about Kendra Rae, but she would find solace in seeing this person before her speaking out. Maybe what Kendra Rae said could have been sugar-coated or maybe she could have said it differently, but she was able to speak out. I wanted to consider all the different ways that we are—quietly for Nella and not so quietly with Kendra Rae—trying to carve out spaces for ourselves and for one another.

AV: I noticed with both Nella and Hazel, and Kendra Rae and Diana, that the novel is exploring the value—or the lack thereof—in Black opinions. We’re looking at whether or not Kendra and Diana should be trusted to put out Burning Heart, Nella’s opinion about Needles and Pins for the editor she works under. What made you want to explore the value of Black work, both labor and writing itself?

I would feel so insecure about having been privileged, but also felt like, ‘I’m still a Black woman in America, the most disrespected woman.’

ZDH: When I first started writing, I had the theme of commodification of diversity in mind, but especially Black bodies and Black work. In general, in our society—as in capitalism—there are so many things that go into what we value and what holds more weight. Nella often struggles with the fact that she’s seen as the Black voice at Wagner, and that’s such a big weight that a lot of Black people who are in these spaces—who are able to get through these walls—have to carry around. It’s a lot of baggage. I don’t know what the answer is on how to navigate that—it’s case by case. We should use our power when we are in these spaces to speak up and do what we feel is right. But also we are human. We should be allowed to just be.

Also Black women aren’t really listened to, ever. That’s the other side of it with Kendra Rae and Diana. “No way white people would want to buy that book,” was most likely what most people at Wagner thought at first. And then it was like, “Oh, but you were right, you’re in Vogue now”. That’s something that we see all the time. As an artist, I also feel that pressure.

AV: The Other Black Girl also questions privilege. We see the privilege of the white employees at Wagner and the higher ups and how that differs, and even the difference of childhoods between Nella and Hazel. What made you zoom in on what privilege means for each type of character in the novel?

ZDH: Every single character has an element of me. Nella the most, of course. When I started writing Hazel, I asked myself, “Who is the cool Black chick that I wish I could be?” Sometimes I wish I had been raised in Brooklyn or Harlem, rather than in the suburbs of Connecticut. I grew up like Nella, in a very white neighborhood and went to a very white elementary school. I was told in high school I talked like a white girl by other Black people. That was a lot to navigate. I was in AP classes and other high level classes and most times, it was me and one other Black person.

Looking back on it now, I know that I was fortunate to be able to go to a really good public school. My dad moved us there specifically because it was the best public school in town. They had all these resources. We were able to do all of these things that a lot of other people, I learned as I got older, were not able to do.

Once I got older, I started to see how these things affected me, and what I really hated was that I was seen as not Black enough. I’ve always had this feeling because I grew up in these ways, and I was in Jack and Jill as a kid. So, that part of Diana’s character is something that resonates with me.

I would feel so insecure about having been fortunate and having been privileged, but also felt like, “I’m still a Black woman in America, the most disrespected woman.” I was always trying to figure out my class privilege and how that interacted with me being a Black woman, especially as I got older. Then I moved to New York and I saw what was happening with Eric Garner, Philando Castile. I saw more Black people in general moving through the world. I thought about this as I was writing the book as well.

AV: Nella and Hazel seem to be fighting for the top spot. At first, there’s some trust, but as time goes on, we realize that all skin-folk might not be kinfolk or the allyship we thought was there might not be. There’s a clear struggle between Nella wanting solidarity, but also wanting to show that she’s the Black employee to trust. Can you tell me more about this?

ZDH: There are white eyes watching them all the time, so they feel like, of course they’re going to be in a microscope because they are the only ones. This is something my dad told me happened with him when he was working at a very white office. Whenever Black people are sitting together in a mostly white place, it’s like, “Are they plotting something? Are they planning something?” But of course, Nella does want to be plotting things with Hazel. Maybe not overthrowing Wagner, but she does love the feeling of “us against the world.”

Nella also expects Hazel to want the same thing. Hazel suddenly doesn’t go with that, and it seems like she’s trying to mess with Nella’s position. Hazel’s code-switching plays a role, too. Nella had been telling herself—and Wagner was telling her, too—that she needs to strip herself of these desires, these wants, to diversify publishing. She was bringing a backup version of herself, whereas Hazel could suddenly bring all of these things to work and still maintain her Blackness. But that comes with a price, because what is Hazel doing to herself in order to be accepted?

That’s why we are so scared. We feel like we have to be a certain way to get through these doors. That’s how I felt. I’m hoping that we can talk about this, and also talk about how to make spaces more inclusive and diverse. Meaningfully inclusive, not just, “Here’s a Black person now, you guys are good right? Okay, bye.”

AV: We don’t see many psychological thrillers in office settings. You mentioned this earlier, when you talked about your influences, but what was it like writing a novel that hits so close to home and how were you able to make this setting both intriguing and sinister?

ZDH: It wasn’t very hard writing a novel close to home because writing Nella’s character was so easy to me, but I made the conscious decision at some point to write in third person. I didn’t want people to actually think this all happened to me. I love my coworkers, my bosses are wonderful. I didn’t necessarily have as many Black friends in publishing as I wanted to have, but I did have people who cared about how I was feeling and completely agreed that things needed to change. But it was hard.

But I’ve worked in a lot of offices. I’ve been working since I was 15 or 16. I worked in the medical records office in my hometown when I was in high school, and I worked at a recreation office in college. I think there’s something so fascinating about being in closed quarters. Even though they have an open floor plan at Wagner and she has her little cubicle, she’s always on display in a way, and even when she thinks she has privacy, she doesn’t.

Everyone can hear your conversations, everyone can smell what you’re eating. There’s just so much I could do with her senses—Nella smelling Hazel when she arrives, watching people walk by her cube. These are all such visceral things and I still remember how these things felt. I knew there could be so many opportunities to play with this drab space and mundane, everyday things, fully grating on Nella and also becoming really sinister and dark.

AV: Is there anything else you’d like readers to know?

ZDH: I really wrote from the heart, from my soul, for me, but also for Black women. I wanted other Black women, not just ones who have worked in these environments, to see themselves in the hair references, the obscure music references, the TV references. It’s been really fun seeing Black women respond to this book, seeing the different things we take away from it. What I want non-Black readers to know is we’re not a monolith. We have very different views on things, we deserve to be heard, and we deserve to be there. There needs to be more of us. We should be in more places, we should be valued for all kinds of things, writing about all kinds of things.

I really hope that this book will show that to the publishing world that thinks, “Readers won’t be into this,” what could be possible. I want there to be more Black books. I want there to be other books that get the attention that they deserve. I want there to be comps in the future. When I was querying my agent, I was trying to think of books that were in a similar space, and it was hard. I just want there to be more.

We’re in the process of writing the pilot script for the Hulu adaptation. I took a whack at the first draft of the script and had so much fun just getting to live in a character a little longer. So book stuff is still my life, but hopefully, the TV side will play a big part in it, too.