Interviews

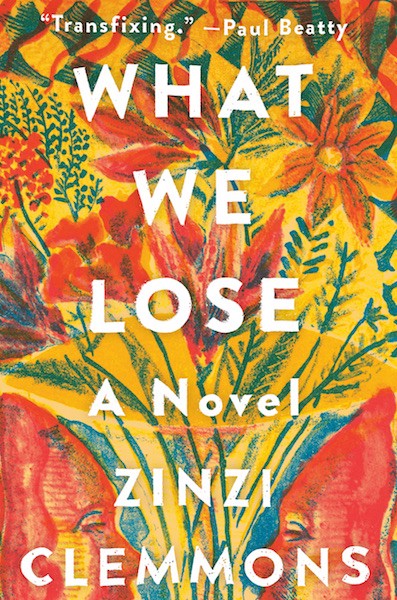

Zinzi Clemmons is Always Willing to Get in Trouble

The author of ‘What We Lose’ on the complexities of race, womanhood, and the privilege of pushing boundaries

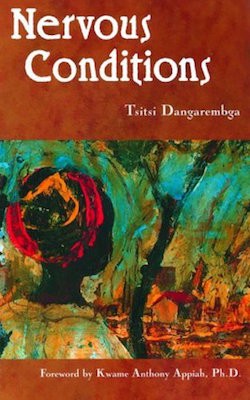

Zinzi Clemmons’s novel What We Lose, for which she was recently named one of the National Book Foundation’s “5 under 35,” doesn’t mince words. The novel is unusual, bringing together many small pieces — a page or two of narration, a graph, a quoted article, a sentence alone on the page. The precision of each of these pieces cuts open the many layers of grief, desire, and identity, and Clemmons leaves them splayed for the reader. After the first few pages, I felt the narrator’s loss of her mother, her fear of losing her father, and my own fears of losing my parents knotting together in my stomach. I closed the book for a week before I could face the rest of it. When I re-opened it, of course, I couldn’t shut it; I read the whole, gorgeous thing in a single sitting.

The novel started for Clemmons as a different book entirely: a traditional, linear narrative, which she was writing as her MFA thesis at Columbia. Shortly after she finished classes, her mother’s battle with cancer took a turn and intensified. Clemmons moved back to Philadelphia to care for her until her death a few months later. “Basically I had this very big life event plop down right in the middle of writing the book,” Clemmons explains. “And, as anyone who’s a writer knows, when those things happen, they will present you with new topics to write about — because it’s really impossible not to write about them.” She began incorporating journal entries about her mother into the manuscript, and eventually abandoned the original manuscript entirely. A new story grew around fragments of journals and research on grief: the story of Thandi, a young woman who, like Clemmons, is the daughter of an American father and a South African mother who is dying of cancer.

Since the release of What We Lose, Clemmons has stayed attentive to the fine details of social issues. Recently that meant calling out the “hipster racism” of Lena Dunham, who had dismissed actor Aurora Perrineau’s accusation of rape by Murray Miller, a writer and producer on Girls. (This interview was conducted a few weeks before that incident.) Clemmons followed her statement on Dunham with a tweet written with the same fearlessness we find in her novel: “To all the haters, harassers and abusers creeping into my timeline, remember this: I brought down a major celebrity and her publication with one Facebook post. Try me.”

On a cold evening in New York and a warm afternoon in LA, I chatted with Clemmons about the complexities of race and womanhood that public discourse likes to gloss over, and the choice to write in a structure of fragments to examine those details.

Alison Lewis: You manage to excavate so many different layers of privilege in this novel. I’m thinking, for instance, of Thandi seeing her mother’s cancer as almost a privilege; Thandi is too embarrassed to tell her friends about the cancer because it’s a disease that’s so well documented and funded — whereas AIDs, at the time, wasn’t. And yet of course Thandi can’t express that embarrassment to her mother because it would be so hurtful… These notions of privilege are so complicated and personal that Thandi feels they can’t be spoken aloud. Did writing about them through fiction free you, in some sense, to go there, to say it?

Zinzi Clemmons: Yeah, absolutely. That was a thought I had at the time: that I would be protected by a novel; I could be more honest. At the same time, I don’t want to make it seem like I never would have said those things [in nonfiction]. I definitely have said things that have gotten me in trouble, even in this book. I’m always willing to get myself into trouble! During the writing process, I didn’t want to feel encumbered by anything.

A Burial Story About Far-Away Family

AL: In that same paragraph about the “privilege” of cancer, you go on to say that the legacy of apartheid is always with Thandi and her family: “not sickness, not suffering, not death could change that.” I wonder if you could talk about that — as an American, I’m not sure I know what it feels like to carry the truth of apartheid daily.

ZC: I think you can understand that as an American, if you replace apartheid with race. The point that I was trying to make that disease, and pretty much all matters of health, completely constrict you in a way that is unavoidable. Especially for young people, it’s hard to wrap your head around: just how little control you have. You might have all of these feelings about a group that you’ve been put in, right — cancer patients, cancer families — but the world looks at you in a specific way, and the way the world feels about it constricts you. Even though Thandi has these feelings about cancer, there is nothing she could ever do to be outside of it. This is something that is put on you; you don’t have any control over it. As a black person, I’m used to feeling out of control. And as people who have lived under the [apartheid] government and have subsequently lived with that legacy, you also do not have control over what the world thinks about you.

AL: I wonder if you could talk about writing about biracial experience, or being a light-skinned black woman? Was it scary to write about those things publicly? Did you worry that people would say, “that’s not my experience”?

ZC: Yeah, of course. And I guess that’s part of why I did it. A lot of the problem of talking about race is that feelings are bound up in it so tightly, and people have a hard time distinguishing their feelings from true systemic issues and things that are offensive. And of course feelings are valid — my book is entirely about feelings! But that’s one part of the argument, and it has dominated the discussion in a way that obscures any kind of progress on the issue. Aside from feelings, what’s at stake in this colorism debate is power and privilege. There are black women like myself who have more privilege than other black women — that’s the issue. I didn’t explain that argument in the book; I came out and just said the ugly things that light-skinned women say as a result of their privilege. I just put it out there. That’s really the only appropriate way do it in fiction because it’s not polemic, and I knew with that approach there would be a reaction to it.

A lot of the problem of talking about race is that feelings are bound up in it so tightly, and people have a hard time distinguishing their feelings from true systemic issues.

An excerpt that contains some of those blunt passages about colorism ran online, and I think some took it as me saying those terrible things that light-skinned women say — they thought that I was saying them earnestly. And, it’s Twitter — this platform is almost designed to proliferate these types of battles. I think a lot of it was just genuine confusion or not knowing that it was fiction. The reactions that happened beyond that were like “you’re black, why would you write this?” I think what it came down to was, “you’re not any better than us.” And that’s really the point, right? Those statements — in the book it’s something like “darker skinned women will always be jealous of you” — I agree that’s fucked up. In that moment, that is a light-skinned black woman not dealing with her own privilege, not recognizing that, and being cruel. And what I would say to that character, if I had the chance to talk to her, is the same thing: “you’re not any better than anyone else.”

The upside to these discussions that generate a lot of controversy is sometimes they put you on the path towards making actual progress. When people are talking about these things, working past that point of discomfort to actually understand what’s going on, that’s what’s important. Personally, as well as in my writing, I don’t really care about the discomfort, as long as there’s a payoff. For black writers, for writers of color and people who are working with identity, we have to make that choice all the time. And I guess my stance on it is, I wouldn’t be doing this unless I was taking risks and pushing boundaries — I’m glad to be able to do that. In regards to my own identity, that’s why I’m here.

One thing that I want people to understand, especially my readers, is that I don’t have the same identity as Thandi; I have a different experience. If you want to be technical, I’m a multiracial person, not a biracial person — but I’ve never called myself multiracial. I think that people should be able to define themselves however they want to, and that’s the choice that I made: I call myself black. I always have. I acknowledge that I have a multiracial experience and I’m interested in investigating it, but I have always been uncomfortable with the ways in which, when we label ourselves as half-this, half-that, multiracial, blah blah blah, we’re sectioning ourselves off from people. There has been so much anti-black racism associated with those categorizations that I think it’s really necessary to look at them with a lot of suspicion. So as far as my identity goes, I say I’m black, and it’s complicated…is pretty much how I’ve always approached it.

AL: You mentioned you’re glad to be able to push boundaries. What are some boundaries you would like to push, and what kinds of messages do you feel aren’t getting talked about that should be?

ZC: The various identities within blackness, within whiteness, within gay communities — publishing tends to homogenize, so right now we have black books, we have some black women’s books, we have a couple of black gay books. But we haven’t yet trained ourselves to look at those complexities within race or within another umbrella identity — to really look at them for what they are. I’ve been compared to Chimamanda Adichie — why? We’re just black women who are writing about Africa! The similarities end there, and I would even disagree with her strongly on many points, particularly as relates to class. And those sorts of arguments, where we’re really talking about who we are and what we care about, that’s where we should be going.

AL: I wanted to ask about violence specific to motherhood; your narrator carefully admits that, in her worst moments, she would gladly hand her son over to a very kind kidnapper because he’s annoying and she can’t deal with him all the time. How did you reconcile this experience of motherhood in the same book that is mourning a mother?

ZC: I felt compelled to investigate the underside. Perhaps this is where I’d be more of an essayist as opposed to a fiction writer — point, counterpoint. It’s incomplete unless you do that. I’m not a mother, so I was the most intimidated writing those sections because I didn’t have any relation to it. I felt like I started getting in touch with the authenticity of that experience — it started feeling realer to me — when I got to lines like that one with the kidnapper because, you know, that’s what makes it complete. I had a feeling that statement would feel authentic, but I didn’t know for sure, so I was nervous about how people with children would respond to it.

Perhaps this is where I’d be more of an essayist as opposed to a fiction writer — point, counterpoint. It’s incomplete unless you do that.

AL: Lastly, both you and I work in publishing, and I get frustrated that it’s such a white industry, which isn’t often ready to look at itself and realize that it has a specific perspective. Do you have thoughts on the direction that publishing is going, and where there are spaces for writers of color to publish in a way that feels true, that isn’t going to be edited into being more…palatable for white readers?

ZC: One thing that’s really important now is how independent presses have stepped up and taken on some of the slack from mainstream publishers. It’s getting harder and harder to get a debut literary novel published, and now the indies are really covering that area. With that growth, you do see room for more writers of color because indies are just open to more things; they don’t have corporate interests they’re beholden to. But I think what that creates — something that I’ve noticed and that I’m worried about — is tokenization. Honestly, writers of color are in vogue now, and everyone is talking about issues of representation! The danger with that is that we only learn half the lesson, and we end up publishing books by writers of color that don’t talk about issues that are important to people of color, that don’t actually move the needle. Look at Tyler Perry. He’s one of the most successful filmmakers working right now, period, and his stuff is trash. It’s absolutely bad for society. So we can increase the color and don’t increase the quality or get any further towards progress. We need to ask who we’re choosing elevate, and who we’re choosing not to, and why are we elevating them? I think that’s the next frontier — not just talking about people’s identities but talking about their messages, and how those two things match up.

Zinzi Clemmons is at work on her next book, a collection of essays, for Viking.

Alison Tate Lewis is editor of the literary magazine American Chordata. Her writing has appeared in the Brooklyn Rail, Somesuch Stories, and Electric Literature.