Reading Lists

6 Famous Writers Inspired by the Occult

Experiencing writer's block? Try joining a ghost club like Arthur Conan Doyle, reading tarot like Shirley Jackson, or studying magic like W.B. Yeats

The occult makes many of us feel uncomfortable, perhaps because we’re so hardwired as humans to hate uncertainty. Yet writing, like life in general, is full of uncertainties; often there’s no saying what words or images will enter our strange minds and work their way onto the blank page in front of us. Whether you’re writing about demonic possession or a fictional character growing up in suburbia, writing is an inherently mysterious process. To understand it better and learn more about their sense of self, many writers, artists and thinkers have looked to the occult, that strange territory between art and science.

The late Victorian period is largely remembered as a period of disenchantment, but it also witnessed a revival of occult and magical belief. In the drive for modernity came a crisis of faith; people sought new means of spiritual development, of communicating with the dead and manipulating reality. As spoils from the far flung reaches of the British Empire returned to the British Museum, including the Rosetta Stone, new and established beliefs and practices (re)-emerged.

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930)

Like his character Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle was a man of reason. He was a trained doctor and a celebrated author in the most logical genre of fiction. Yet he also became a prominent public proponent of spiritualism, a new religious movement whose adherents believed the spirit survived death, and could be contacted through séances. Spiritualists found comfort in the belief that death was only the death of the material self.

Like Charles Dickens, Doyle was a member of The Ghost Club, a paranormal research organization.

Deaths in his family, including the death of his son in 1918 during the Battle of the Somme, and his brother in 1919 of pneumonia, likely reinforced his beliefs, though Doyle became a spiritualist before these bereavements. In earlier life, like many of his contemporaries, he dabbled in mesmerism and expressed interest in other esoteric ideas, but according to biographer Christopher Sandford he may have politely turned down an invitation to join the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

Like Charles Dickens, Doyle was also a member of The Ghost Club, a paranormal investigation and research organization. In 1983, Doyle joined the British Society for Psychical Research, and in 1925, he became president of The College of Psychic Studies in London, an institution which still opens its doors to students eager to develop spiritual awareness.

Bram Stoker (1847–1912)

Some say Bram Stoker was a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Whether or not the rumors are true, he was likely exposed to some of the order’s ideas through friends who were, including J. W. Brodie-Innis and Pamela Coleman Smith.

We learn little of Count Dracula’s early life, but we know he had a deep knowledge of alchemy and black magic. Like many writers of his era, Bram Stoker was likely familiar with mesmerism, or animal magnetism. Based on the theories of Austrian doctor Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815), mesmerism claimed that practitioners could manipulate a “universal fluid” that ran through all matter. It piqued the curiosity of several prominent scientists, and for a while “caused not a few Victorians to re-evaluate traditional magic,” writes Thomas Waters in Cursed Britain. Among Count Dracula’s supernatural abilities are telepathy, the power of illusions and hypnosis, likely derived from this widespread belief in mesmerism. Philip Holden notes “it is difficult to find a late Victorian novel that does not in some way touch upon hypnotism, possession, somnambulism, or the paranormal.”

To literature scholar Christine Ferguson, the clearest occult borrowings in Dracula are structural. Professor Abraham Van Helsing enlists a team of vampire hunters, who swear an initiatory oath of secrecy in order to gain the tools necessary for fighting against vampirism, or black magic. This process of concealing and revealing occult knowledge, says religious studies scholar Kocku Von Stuckrad, is an integral part of Western occultism.

One reading of Dracula: Modernity cannot kill vampires or their hunters, or the connections humans have with the old gods and spirits. It just turns them into secret occult beliefs, practiced underground, from which only a select few have the tools and knowledge to defend themselves.

W. B. Yeats (1865–1939)

In 1891, “a neurotic German” named Mrs Ellis banned W. B. Yeats from her Bedford Park home because she thought he was bewitching her husband Edwin Ellis, with whom Yeats collaborated. She may well have been right.

Most significant for Yeats was his time in the secret initiatory order The Hermetic Order of The Golden Dawn.

Yeats was one of his era’s great searchers. Inspired by Irish folk tales and the work of Blake and Swedenborg, he studied Eastern and Western religions, joined the Theosophical Society, and in later life explored spiritualism. Most significant for Yeats, perhaps, was his time in the secret initiatory order The Hermetic Order of The Golden Dawn. Initiates (among which were Annie Horniman, Florence Farr, Arthur Machen, Aleister Crowley and allegedly E. Nesbit), worked their way through levels of magical study and practiced ceremonial magic in pursuit of the “hidden knowledge.” The curriculum drew from multiple antique sources, including medieval grimoires, tarot, papyri from the British Museum, freemasonry, the work of Elizabethan alchemist and astrologer John Dee, and an 1887 book written by the order’s co-founder MacGregor Mathers, The Kabbalah Unveiled.

Writers and critics mocked Yeats for his fascination with the uncanny, often distinguishing the poet from the magician. Among them, Terry Eagleton in the [London] Independent wrote: “Yeats was a lot sillier than most of us. Few poets of comparable greatness have believed such extravagant nonsense.” But in 1892 Yeats wrote this in a letter to his mentor John O’Leary: “The mystical life is the centre of all that I do and all that I think and all that I write.”

Sylvia Plath (1932–1963) & Ted Hughes (1930–1998)

In a letter to her mother dated October 23, 1956, Sylvia Plath wrote that when she and Ted Hughes moved in together, they hoped to make a team “better than Mr. And Mrs Yeats.” He would be the astrologer, she wrote, while she would read the tarot.

In the early days of their relationship, Plath was curious about Hughes’s knowledge of astrology. (Years later, during a visit to his family home in Yorkshire in 1960, she heard the rumors about his mother Edith, who—according to Plath’s biographer Paul Alexander—”studied magic and passed the knowledge on to her children.”)

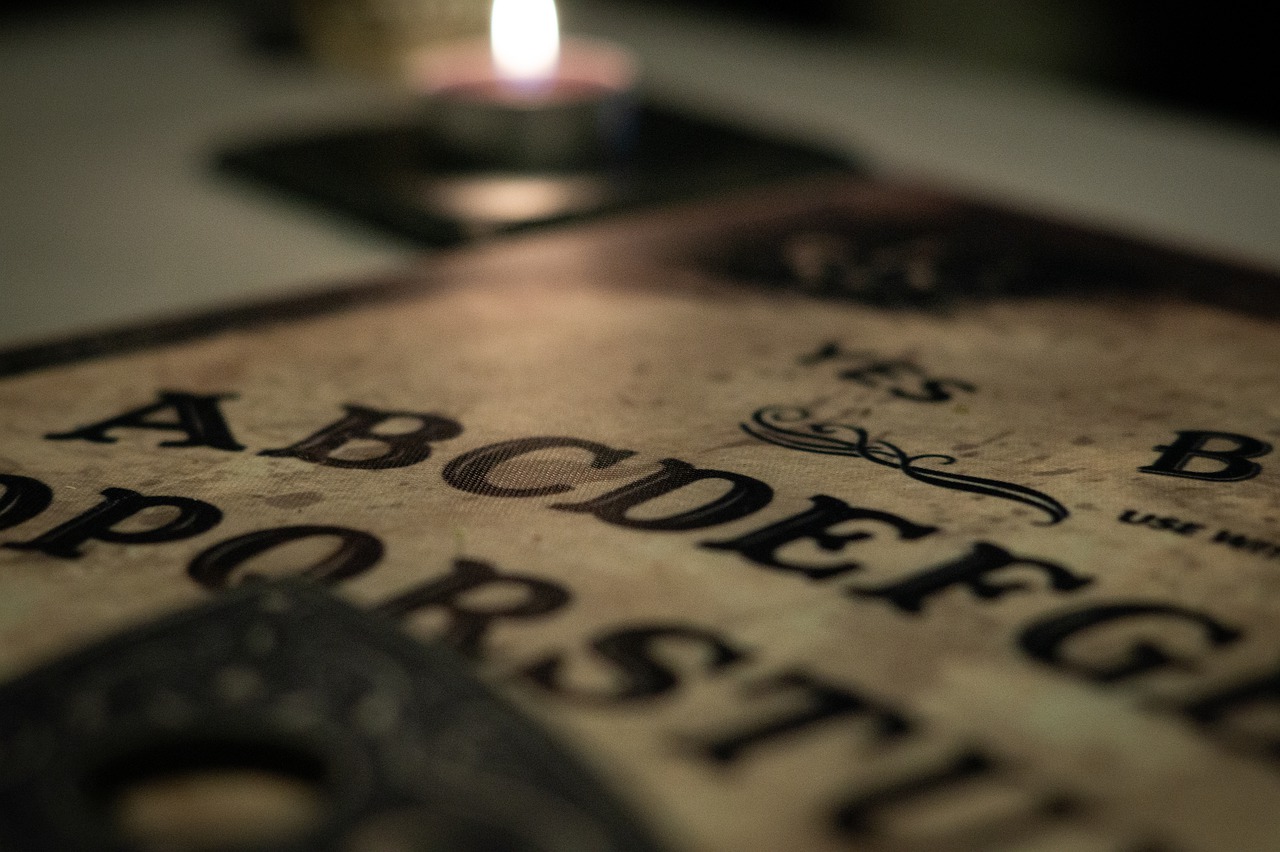

She and Ted regularly consulted a homemade Ouija board they’d made from a wine glass, cut-out letters, and a coffee table. Through private seances they met many spirits, among which were Keva, Pan, and G.A, Alexander tells us; the latter suggested he could predict the weekly football pool, but ultimately got it wrong. The spirits were more helpful in providing artistic inspiration. Plath’s verse poem Dialogue over a Ouija board: a Verse Dialogue, Hughes claimed, was basically a transcript of a conversation he and she had with spirits Sibyl and Leroy. Plath thought the poem so obscure that it wasn’t published until after her death in Collected Poems.

Plath made a ritual bonfire from Ted’s fingernails, dandruff, and manuscripts.

In 1962 Hughes left Plath for another woman. Plath made a ritual bonfire from Ted’s fingernails, dandruff, and manuscripts. Here the history becomes mythical: some say she did this to kill her cheating husband—an act of witchcraft. Her poem “Burning the Letters” suggests she was trying to ascertain the name of Ted’s lover. By some accounts, a single piece of paper fell by her foot revealing the name. According to Ted Hughes biographer Elaine Feinstein, the woman telephoned their house once the bonfire was lit, and Plath answered. Either way, soon after lighting the fire, Plath learnt the other woman was Assia Wevill.

Reaching out to another world, or the lower reaches of her internal world, helped Plath write some of her best poems. As the poet Al Alvarez writes, perhaps this also came at a cost. With a history of mental illness and one prior suicide attempt, Plath had already been to hell and back—but Hughes’s own demons may have helped Plath sink further into the darker chambers of her mind.

William S. Burroughs (1914–1997)

William S. Burroughs was obsessed with finding order in the chaos. In pursuit of visions, he scried in mirrors and experimented with psychedelics and other drugs, which he documents in The Yage letters. He explored aforementioned animal magnetism in his first published essay. He also accidentally killed his wife when drunk. (His explanation? Demonic possession—he was being controlled by the “Ugly Spirit.” He always sought, as “order addicts” tend to do, an explanation for the seemingly unexplainable).

From the Dadaists and Surrealists, Burroughs borrowed and helped popularize the cut-up method, whereby he would cut up a complete text and rearrange the pieces to create a new one. In his science fiction series The Nova Trilogy, he explored his obsession with control and addiction and explained how and why he employed this method. He aimed to destroy “word and image locks,” which he believed enter, shape, and control our minds by locking us into conventional patterns of thinking, and keeping us trapped in a false reality. The Ticket That Exploded (1962) is the second book in the trilogy, and in it Burroughs introduces the concept that language “is a virus from outer space.” He tells us “modern man has lost the opportunity of silence,” and challenges us to “Try to achieve even ten seconds of inner silence … You will encounter an organism that forces you to talk. That organism is the word. In the beginning was the word. In the beginning of what exactly?”

The cutup method, he believed, could free us from this language virus by exposing a true, hidden meaning. This he believed could break down our conception of time, among other things:

When you experiment with cut-ups over a period of time you find that some of the cut-ups in re-arranged texts seemed to refer to future events. I cut-up an article written by John-Paul Getty and got, “It’s a bad thing to sue your own father.” This was a re-arrangement and wasn’t in the original text, and a year later, one of his sons did sue him…Perhaps events are pre-written and pre-recorded and when you cut word lines the future leaks out.

Shirley Jackson (1916–1965)

Jackson’s dark, psychologically unsettling plots were not born out of dark nights in gothic mansions in the woods; she imagined many of them in the drudgery of domesticity. “The Lottery” was one such story, conjured up while running errands in her ordinary town. It was so shocking to readers of the New Yorker at the time that many cancelled their subscriptions. Jackson had a knack for seeing and exposing everyday evil.

Jackson was marketed as a witch by her first publisher, who wrote that ‘Miss Jackson writes not with a pen but a broomstick.’

Unsurprising, then, that she was marketed as a witch by her first publisher, Roger Strauss, who wrote that “Miss Jackson writes not with a pen but a broomstick,” and by her husband, who wrote of Jackson in the biographical note to accompany The Road in the Wall: “…She is an authority on witchcraft and magic, has a remarkable private library of works in English on the subject, and is perhaps the only contemporary writer who is a practicing amateur witch, specializing in small-scale black magic and fortune-telling with a Tarot deck…” This was a persona Jackson sometimes wore with zeal, sometimes denied.

Did this private library really exist? Jackson knew well the history of the Salem witch trials. In her non-fiction work the Witchcraft of Salem Village she showed how the town fell into mass hysteria, pinning the blame for its troubles on a number of women and some men, all trialled, some executed. Scapegoating, reminiscent of witch hunts, is a recurring theme in her works, including her novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle and her short story “The Lottery.”

Her biographer Ruth Franklin tells us Jackson also read tarot cards. The protagonist of her novel Hangsaman, Natalie Waite, is an obvious nod to the maker of the iconic Rider-Waite-Smith deck, conceived by the occultist Arthur E. Waite and illustrated by Pamela Coleman Smith. The novel draws on the symbolism of a card from the major arcana, The Hanged Man, which can indicate spiritual transformation.

Seeing reality from the perspective of the hanged man is central to Jackson’s fiction. In a lecture on writing (“Experience and Fiction in the posthumous collection Come Along with me), Jackson wrote: “I like writing fiction better than anything, because just being a writer of fiction gives you an absolutely unassailable protection against reality; nothing is ever seen clearly or starkly, but always through a thin veil of words.” Franklin emphasises that “…on some level writing was a form of witchcraft to Jackson—a way to transform everyday life into something rich and strange, something more than it appeared to be.”