essays

DOUBLE DARE: Point Horror

by Alice Sola Kim and Meghan McCarron

Writing friendships famously don’t involve much writing, but they tend to involve a lot of books. We met ten years ago at the Clarion West workshop, two nervous college kid weirdos who wanted to write the kind of genre-bending work we’d devoured as readers. Over the course of six weeks, we discovered a shared love of everything from obscure YA to hyper-popular literary novels to translated experimental classics. We’ve never lived in the same city since, but over ten years we’ve exchanged countless emails, phone calls, texts, manuscripts and, most importantly, book recommendations.

But here’s the thing: we could leave books at each other’s apartments or ardently recommend novels all we wanted, but life is fast and weird and we’re both pretty forgetful. For this column, we will assign books that the other has to read in a timely fashion. Sometimes this will be because we loved a book. Sometimes it will be because we find it interesting, or terrible (yes, we will be trolling each other). In any case, you know that glorious feeling you get when someone has actually read the book that you recommended to them? We plan to experience that on a regular basis.

Up first is a weird trip back in time to one of the first things we ever bonded over: The Point Horror series. These were the spinner rack books, the covers with oozy-looking embossed titles and screaming teens. R.L. Stine, Christopher Pike, Caroline B. Cooney, Diane Hoh, Richie Tankersley Cusick.

Point Horror was grindhouse for girls. The disreputable and grim, the stark and shoddy — but for the likes of pre- and early teen us. Not more than we could handle. For a time, it was perfect; it was the exact kind of wrong we were seeking.

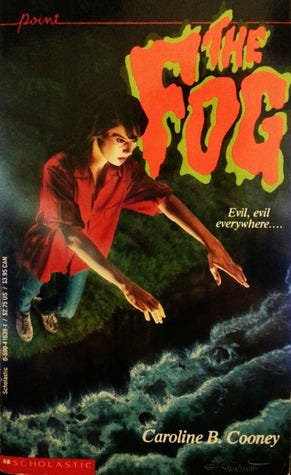

Meghan’s pick for Alice: The Fog

When I was in fourth and fifth grade, I read my way through the entire fiction section of my school library. Or at least I think I did: the reading was a survival tactic, and my memory of the books I inhaled is non-existent. I do remember the despair I felt standing in the stacks, staring at a shelf full of books I’d already read. I don’t remember which of these novels scared me the most; the real answer is probably “all of them.” But when researching our Point Horror glory days, I saw the cover of The Fog and thought, “Oh no. Not that book.”

Of the two of us, Alice is much more the horror writer and the horror fan. She’s the one who re-introduces me to all the bizarre details from Christopher Pike novels I’ve tucked into my subconscious. The Fog is a gas lighting horror story set at a remote boarding school, all words I know would be Alice-approved. Her work is infused with an uncanny darkness that can turn on a dime from hilarious to terrifying, and has and especially keen eye for the dynamics between unlikely communities forced together: she’s even written a story set at a boarding school. But more than that, I was interested to hear her take on a book whose mere thought filled me with dread twenty years later.

Alice’s take on The Fog:

Fog pulls off a neat trick. Author Caroline B. Cooney intended it to be “starter horror” with no bloodshed. But by sidestepping the usual Point Horror standbys of gory-boring stabbings and bludgeonings, Fog instills a deeper sense of horror, one that disturbed me despite my too-oldness for this shit. Thanks, Meghan!

Class is an important part of the horror in this book (and in life, right). Our hero Christina is thirteen, excited to leave her tiny island off the coast of Maine to attend high school on the mainland, along with her older friend Anya and two boring boys. Christina is brave and stubborn and has naturally tri-colored hair — brown, silver, and gold, (yeah, I don’t know either) — but all this is meager protection against the horror we already know she will encounter: that of being a poor kid in a school of rich dickheads. The dickheads mock the islanders for their poverty, their slang, and their rumored lineage of criminals. It being coastal Maine, close attention is also paid to how one wears one’s boat shoes.

The other horror in Fog, inseparable from the sense of class horror, is that Christina and her island compatriots have to board with these smooth assholes named the Shevvingtons in their cliff-top house. The boarders’ bedrooms are chosen and decorated to be maximally creepy, and Mrs. Shevvington serves up gross dinners and spiteful insinuations.

Yes, dinner is food and a creepy bedroom is shelter — but what Fog really highlights is the overwhelming discomfort of such a situation. Of being surrounded by people who can treat you with such an utter lack of dignity — who will treat you worse and worse — because you’ll still never be able to repay them for their kindness. Reading, I felt a smothery, awful sense of powerlessness. I know about the free lunch tickets that Christina uses and I know what it is to be an unwelcome guest, to silently eat what is handed to me or not eat what is not given and to say thank you in response to any kind of treatment.

High school principal Mr. Shevvington is the silver fox hottie, the one who dominates with his charisma and slick talk, the one you would just do anything to please. Meanwhile, Ms. Shevvington, the English teacher, is the nottie, a Dolores Umbridge-esque figure who smiles sadistically with stubbed yellow teeth and controls with false concern and unending rules. It quickly becomes clear that the Shevvingtons’ sole goal and pleasure is to torment and gaslight young women, eventually driving them mad.

Why? We don’t find out. But it’s got to be at least partially a weird sex thing, subtextually speaking. It’s also yet another class thing. Poor Anya, glam and smart, succumbs to a gaslighting onslaught involving a poster of the sea that keeps changing, the noisy tide, and a creep in a brown wetsuit. She goes insane, quits school, and works in a laundromat. Everyone pities her; everyone is grateful to the Shevvingtons for all the help they’ve tried to give Anya. As the Shevvingtons sadly say, “We always thought she would become a wharf rat and now she has.” “Wharf rat,” of course, is the book’s pejorative for a particular kind of working class girl.

This is intensely horrifying; thank goodness Christina is a bad bitch. Throughout, her mantra to herself is, “I am granite.” She is blunt and forthright, sometimes bratty. Later, when Christina pukes on some mean girls, her first post-vom thought is, “What a weapon.” Still, the Shevvingtons do their harrowing best to mess with Christina. Among other things, they ask her to fill out a highly super official form requesting a list of her worst fears (!), and subtly bully her in front of her fellow students. Though Christina isn’t immune to Mr. Shevvington’s psycho hot daddy charms, she ultimately sees him for what he is. “…[S]he remembered that she was granite, not a tern. That Mr. Shevvington did not have the eyes of a mad dog, but of a man who wore contact lenses.”

Yeah, fuck your contact lenses, Mr. Shevvington!

The horror is not the sea. It is not a supernatural force. It is the people who think you are beneath them and will stop at nothing to force you to live out their fantasies of who you are, who you really really are, so that you give up and prove them right. And worst of all, these are the people who often hold all of the institutional power, so that you alone — without parents or friends or teachers — must remember that you are granite.

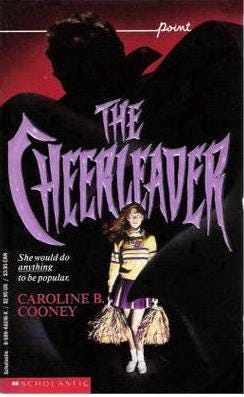

Alice’s pick for Meghan: The Cheerleader

The Point Horror book I chose for Meghan is The Cheerleader by Caroline B. Cooney. This one I do remember pretty clearly. There’s a vampire, who isn’t so much a solid being as an unstable cluster of characteristics. He’s practically Cubist. Here’s the teeth; here’s the spongy, decaying skin; here’s a shard of cloak in the corner of your eye. You never see everything at once.

Then there’s Althea, the lonely girl up in the shuttered room. Because Meghan’s writing is so great at depicting complex relationship dynamics, such as push and pull between wanting/not-wanting, I thought she might find Althea and the vampire kind of interesting. One really uncomfortable thing about this book (and the two others in this trilogy) is that the main characters are made complicit in the vampire’s evildoings. The vampire wants, and because the girl also wants — popularity or beauty or intelligence — the vampire gets.

Meghan’s take on Cheerleader

Althea has a problem: she wants to be a cheerleader but didn’t make the team. This may or may not be because she has no friends and lives in a creepy house with a vampire. In exchange for awakening him (she opened the locked room in a tower, of course), the vampire promises to make her popular, provided she supplies a victim. After she delivers the energies of a young, pretty freshman, Althea makes the squad and befriends the most popular girls in school. She gets a boyfriend and spends a lot of time at Pizza Hut. But the vampire keeps demanding victims, and he’s clearly not just making them “a little tired.” Finally, Althea tries to sacrifice herself to the vampire, only to reject her desire for popularity and escape.

The vampire is the gross, leechy variety: he smells of rot and has mushroom-soft skin. He taunts Althea in that sexual-yet-sexless way vampires excel at when they’re definitely not boyfriend material. His disgusting physical presence is mirrored by the delicious, intoxicating physicality of cute boys. A YA writer friend once pointed out that for all its flaws, Twilight is uniquely invested in Bella’s physical feelings of desire. I could defend The Cheerleader similarly: Althea is a great assessor of boy flesh. There’s a short scene of heterosexual bliss when she rides in the car between two rival suitors, relishing every bump of the knee. She delights in the attentions of not one but two boys with muscles, turns to jelly when one rests his chin on her head. She is equally fascinated by the football team’s nervous faces on the way to a game, a rare crack in their masculine facade.

Althea also meticulously worships the beautiful, perfect cheerleaders she aspires to become. The freshman she sacrifices is a lovely and languid blond; the brunettes on the team “sparkle.” As a closeted kid, I remember this intense, totally not gay worship of female beauty. It served to only further entrap me. Girl culture is a paralyzing amalgamation of homoerotic affection and strictly enforced homophobia: you braid your friend’s beautiful hair while discussing how disgusting it would be to kiss a girl. I used to stare at the lovely popular girls and tell myself I just wanted to be thin and beautiful like them. That my desire was jealousy. I don’t know if I read Althea as closeted here, but if anything, she finds the girls lovelier to look at than any of the boys, who are barely described outside of their touches and smells.

Pizza Hut plays a bizarrely central role in the novel. The popular kids meet constantly in a hidden-away back booth, never actually consuming pizza, just digging the soda and the scene. When someone puts on music in the jukebox (did Pizza Hut have jukeboxes?) Althea declares, “You can’t dance in a Pizza Hut!” And then she does. This is perhaps the happiest moment in the book. There was a Pizza Hut near my high school. No one was hanging out at that weird sad restaurant. My friends and I went to Friendly’s, but we were not cheerleaders. In a way, it’s a weird warping of high school for younger readers: the characters all guzzle soda like it’s booze and hang out at a restaurant for kids.

More than anything else, reading this novel dug up the tyranny of “popular” in middle school life — and the unrelenting finger-shaking at wanting to be popular. Althea’s actions are so heartless she resembles a Shirley Jackson character: a crazed outsider wreaking havoc to attain something she’s entirely unfit for. The girl lives in a haunted house with a locked tower. Of course she’s not cheerleader material. For all we know there’s a missing chapter in the book about poisoning her parents, who never appear. This queasy undertow of evil comes, I suspect, from contradictory characterization rather than literary intent, but the book goes to a darker place than something more polished might have.

Though, really, the novel is too hard on Althea, the maybe-orphan weirdo in the thrall of a vampire who fucking lives in her house. This musty, mushroomy monster is psychologically torturing her, and it turns out all she has to do is stop wanting to be popular. That’s an especially mean manifestation of the advice all adults, including me, give young women: forget being popular, just be yourself! The Cheerleader adds: And any shortcuts you take are evil and totally on you!

That’s the message that would have scared me at that age; maybe it’s what scared Alice too. Because what’s wrong with wanting fun friends and a cute boyfriend, exactly? The scene that moved me most was Althea’s first lonely search for somewhere to sit in the cafeteria. When I hit high school, my friends all ditched me too, and I made a much less successful gambit for popularity via team sports. That hopeless, clawing loneliness of having no one to sit with while you eat your sandwich is not trivial: it’s a sharp reminder of much larger problems. If I could have escaped that minor hell with help from a monster, I might have, too.

***

Alice Sola Kim is a writer whose work appears in Tin House, McSweeney’s, Asimov’s, and Lightspeed. Her website is Alicesolakim.com.

Meghan McCarron’s writing has recently appeared in The Collagist, The Toast, and Gigantic Worlds, and her short fiction has been a finalist for the Nebula and World Fantasy awards. A food and restaurant obsessive, she is the editor of Eater Austin.