essays

MEDIA FRANKENSTEIN: College

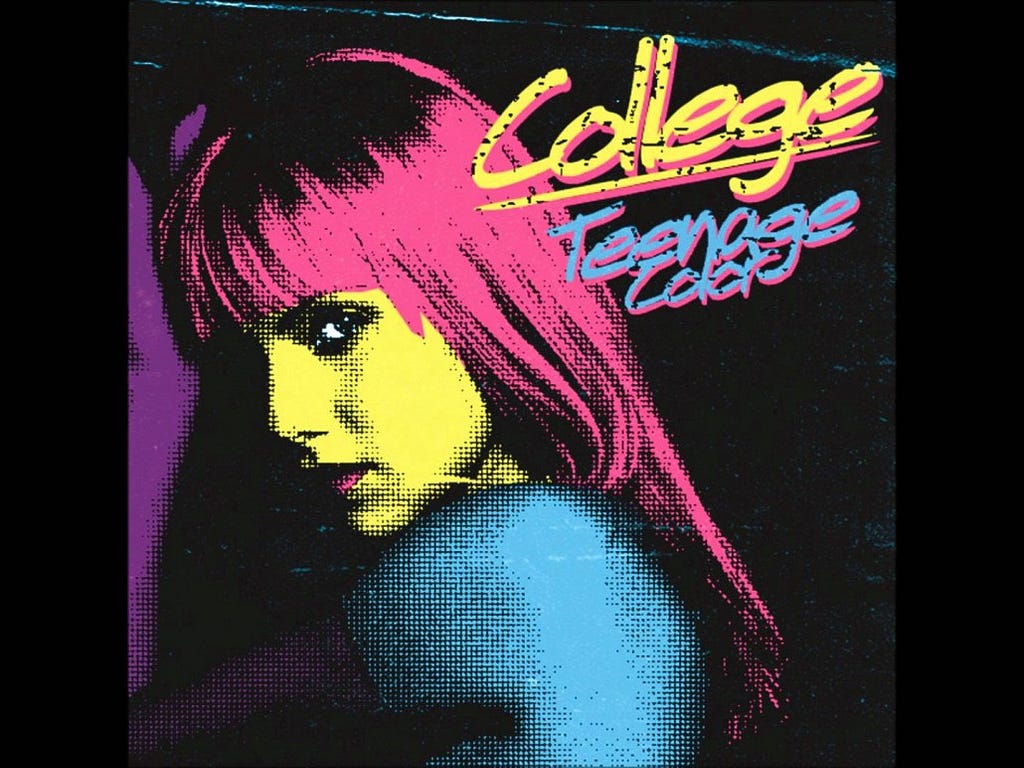

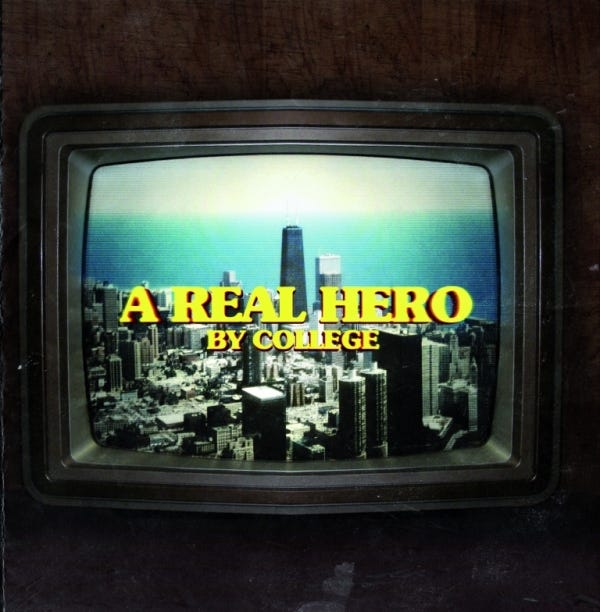

THE HEAD: College’s Teenage Color (2008) & A Real Hero (2011) EPs

People say about college before you arrive there: it marks your best and freest years. Except for that job in the art-slide library or whatever work-study you’re doing part-time, your prime responsibility is meant to be pursuing knowledge. That — and oh just everything that goes into being a real human being: feeding yourself (which you don’t really do), discovering sex (which you often do badly), expanding your mind and polluting your body (you do this, maybe, most of all), managing money (at which you fail hugely). And while bemoaning the lot of those who are lucky enough to attend college is equivalent on some level to looking the gift of Western privilege in its extensively orthidontured mouth, college can be, as you’re fumbling through it, a bewildering, scary, exuberant time. What you remember is what you are told, not what you dealt with in the moment, and the widely acknowledged surreal melancholy that lies at the heart of the college existence is lost in the mind of the so-called adult. The older you are, the less you know. What better group to score the surrealism of life at the foot of the ivory tower than David Grellier’s own College, specifically the one-man French music collective’s EPs Teenage Color (2008) and A Real Hero (2011). Laying down lonely, night-cruising drum tracks beneath majestic synth overlays and an aesthetic suffused with John-Hughes-era nostalgia, College’s Teenage Color and A Real Hero EPs — an abbreviated form perfectly suited to your college attention span — sound like they might’ve been composed in your poster-smothered dorm room on an all-nighter diet of Aderall, Dr. Pepper and Haribo candy. While Teenage Color is a dancy, neon-bright record on which Grellier’s reverberant waves of synth melancholy enter on the heels of a Duran Duran drum section that wouldn’t be out of place on a Thursday night in whatever humid, Miller-Light-smelling basement you were fond of spending “the weekend” in, A Real Hero is in some ways Teenage Color’s inverse. As on “Critical Mass,” A Real Hero’s standout track, Grellier’s keyboard lamentations (more Joy Division than Duran Duran) take center stage, and a darker, more meditative experience begins to unfold. Indeed the former record (Teenage Color) might be more appropriate to the heedless beginning of college, the latter (A Real Hero) to the dorm fire sale comedown that marks its conclusion. It’s this quality of ironic juxtaposition — not only between the records but within the music itself –that made College perfect for Nicolas Winding Refn’s 2011 “high trash” noir Drive, in which an outwardly gallant stunt driver/getaway man (Ryan Gosling) seeking to protect a single mother (Carey Mulligan) takes a sharp turn into macabre depravity. College’s collaboration with Electric Youth, the titular song “A Real Hero,” did volumes to underscore Winding Refn’s interrogation of on-screen violence in the film’s soundtrack alongside excellent cuts from Kavinsky, Desire and The Chromatics. “A real hero and a real human being,” goes the song’s ethereal female chorus before Gosling’s “Driver” proceeds to beat people to death in elevators and drown them in the ocean in between cruising the streets of a cotton-candy-colored L.A. It’s this kind of discrete shift between shadow and light, concreteness and surrealism that defines College as a band and make them a fitting soundtrack, furthermore, for the college experience itself. A tree-bordered lake in a winter landscape suctioned dry of its water before the first freeze; the sound of the cocks of the cross-country team flip-flopping against their legs on a 2 a.m. streak through the undergrad quad; the vertiginous feeling of being too drunk in some rooftop garden too far from your room and the limitless feeling of just letting go, bushes banking up at you.

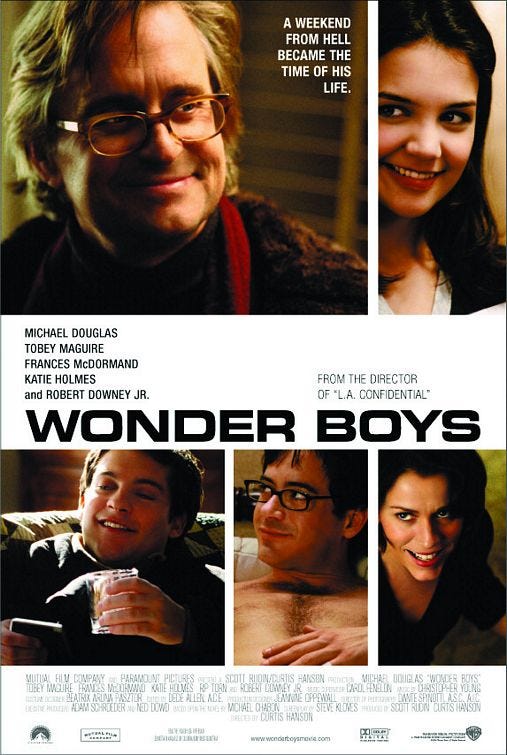

THE TORSO: Wonder Boys dir. Curtis Hanson (2000)

There’s a scene toward the end of Curtis Hanson’s Wonder Boys (2000) that has stymied novelist and creative writing professor Grady Tripp (Michael Douglas) standing at the edge of Pittsburgh’s Monongahela River in between a pregnant diner waitress dressed in the wedding-day furs of Marilyn Monroe and a James Brown lookalike with a pistol as reams of paper scatter on the wind, blowing irretrievably into the water. Tripp’s pansexual editor Crabtree (Robert Downey Jr.) manages to catch a few stray sheets, having moments ago crashed Tripp’s car with the papers inside it into the side of a nearby warehouse. Semi-spoiler alert: the papers swallowed by the Monongahela comprise the only copy of Tripp’s 2,000 pages-and-counting second novel, which he hasn’t been able finish since his first book — a literary send-up: The Arsonist’s Daughter — set a critical bar too high to surmount. The tragi-farcical nature of this scene speaks not only to the liminal unease of being in college but also the tone of the film overall, which is rooted in gloomy absurdism and whimsical paradox. Essentially, Wonder Boys follows Tripp, a philandering pothead with tenure whose wife has recently left him and who has managed to impregnate his Dean (Frances McDormand), as he purports to serve as a role model for spooky, fiction-wunderkind James Leer (Tobey Maguire) over the course of several chaotic days. The film’s most compelling irony lives in the match-up between Tripp and Leer, who are constantly outdoing each other on the scale of who has his shit together less: Tripp is a man-child, where Leer is a child-man; Tripp fathers Leer who in turn fathers Tripp, daring him to be the idol that Leer, in his innocence, wants Tripp to be. In one scene, after being bitten by the Dean’s Rottweiler Poe, Tripp takes down two Codeine with a nip of whiskey before offering some to his student, Leer (really, only one of many prosecutable and inappropriate gestures Tripp makes in the course of their time together). When Leer says, “No thanks. I’m fine without them,” Tripp barks, “Right… You’re fine, all right. You’re fit as a fucking fiddle.” Leer isn’t. Lying somewhere “on the spectrum,” Leer is also a compulsive liar and a strident manipulator, not to mention an obsessive when it comes to the dark, suicide-riddled history of 1940’s Hollywood. Such conspicuous ironies and quirks as these, however, are not the only driving forces when it comes to the film’s unique sense of the absurd and the surreal. Based on a novel of the same name by Michael Chabon, Wonder Boys follows a picaresque structure (A leads to B leads to C leads to D) and recommends itself to the instability of the college experience through idiosyncratic set-pieces: a dead dog in the trunk of a car alongside a tuba in a calf-skin carrying case; a 6’ tall transvestite making the rounds at a faculty mixer; Tripp (perhaps Michael Douglas’ greatest achievement as an actor) driving around Pittsburgh in a tattered, pink housecoat with half of a joint forever burning in his mouth. Tripp also suffers from what Leer describes as “spells” (to which Tripp responds: “Jesus, James, you make it sound like we’re in a Tennessee Williams play. I don’t get spells.”), worrying blackouts that land him on his back at inopportune moments that, when combined with his Willy-Nelson-grade pot intake, lend the film’s already surreal goings-on a dimension of narrative unreliability. And although Wonder Boys isn’t your average college romp, falling partly into the category of academic satire à la Kingsley Amis’ Lucky Jim (1954) or Jane Smiley’s Moo (1995), in some ways that’s the point. While Tobey Maguire’s Leer and Katie Holmes’s Hannah (who Tripp refreshingly doesn’t sleep with), both students, help to root the story concretely in a college milieu, Douglas’ novelist living in a state of arrested development reinforces the surreal limbo within which the younger characters find themselves; in some ways Douglas is their foil, in other ways they serve as his. The film’s picaresque circumstances become an externalization of the characters’ inner turmoil, the ebbing away of their sense of the selves they never really knew they weren’t. The film ignores answers in favor of questions: though people may age, do they ever grow up? They might not, quite, but that’s okay.

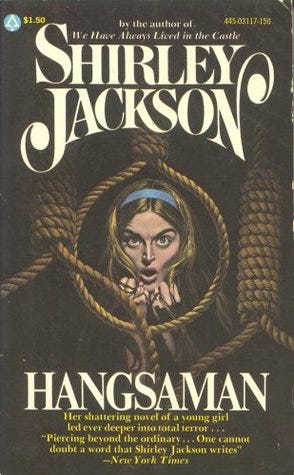

THE LEGS: Hangsaman by Shirley Jackson (1951)

If College’s EPs and Hanson’s film serve as wry overtures to the weirdness of being in college, then Shirley Jackson’s Hangsaman (1964) is a full, booming orchestra of it, and perhaps the first novel to use elements of sublime terror to address the process of obtaining a B.A. Unlike other psychological thrillers, however, there is no slow burn in Hangsaman, whereby cracks in the main character’s psyche presage a grand collapse; rather, Jackson’s novel and the protagonist at the center of it, Natalie Waite, are weird from the get-go and only get weirder. In this sense, the novel’s surreal nature isn’t limited to college alone; college is a petri dish that serves to augment a preexisting disorder and when Natalie gets there, she blossoms all right, but never in the way you’d think. Here is a girl who engages with an imaginary “detective” in her head about an unspecified murder; here is a girl who carries on a coquettishly literary written correspondence with her father, a pedantic minor scholar of English letters (one of her letters to him begins: “Dear Sir Knight: It was not you then, caroling lustily under my window these three nights past.”); here is a girl whose late-night study breaks take her not to the all campus dining center for grilled cheese with tomato but to wander, while singing, the freezing cold campus. Add to this a sexual trauma that Natalie suffers at the hands of one of her father’s colleagues before she leaves the nest and you have a brooding, simmering novel in the tradition of Emily Bronte’s Jane Eyre or Patrick McGrath’s Spider about the considerably more universal trauma of growing up. Hangsaman is similar to both Wonder Boys and the College EPs in the sense that it’s full of contradictions that belie the free wheeling circumstances of its plot: girl goes to college, finds self, journeys on. The school in Hangsaman is modeled roughly on Bennington College in Vermont where Jackson’s husband, the literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, taught. While it purports to be progressive, a place where gifted girls like Natalie go to become sophisticated women, one of Natalie’s first friends there is Elizabeth Langdon, the erstwhile student and now kept wife of Natalie’s lothario English professor Arthur Langdon. Elizabeth vacillates between martini-sodden bitterness and uncomfortable-making adoration; when she isn’t reinforcing staid gender binaries, like always having supper and a pitcher of cocktails ready for her husband when he arrives home after a hard day of flirting with the prettier of his female students, she makes for an amusing if excruciating scene-stealer next to understated Natalie. (In Hangsaman as opposed to Wonder Boys, the professors do sleep with their students.) And then there’s the fracture in Natalie’s psyche, manifest toward the end of the book in a fast “friend” named Tony that she makes while wandering her dormitory; although Jackson never states explicitly that Tony is a damaged extension of Natalie, you pick up the sense that they’re somehow related. The girls go on a spirit quest to the edge of the town, where the “wilderness” starts. Tony tells Natalie this as they’re walking: “ ‘We are on a carpet,’ … ‘It unrolls in front of us, but in back of us it rolls up and there is nothing under it.’” What a perfect assessment of college right there! Beyond the solo cups, the void. Natalie grows, though we’re not sure how much before the end of her ordeal. We’re left with the sense that the book is just one of many dark chapters in Natalie’s life, this one perhaps to be repeated. The psychological chiaroscuro of Hangsaman, a college novel about trauma, alienation and the lengths to which our minds will go to protect us from the terror of being alive is the ultimate paradoxical entry in a genre most comfortable with Greek system antics and pre-packaged self-discovery. In the College EPs, Wonder Boys and Hangsaman, college is nothing at last but the distance between expectation and coming up flustered. But damn if it doesn’t look good from behind. What nobody tells you before you arrive is everything you’ll never know.

ALTERNATIVE CUTS:

Salem’s King Night (2010); Springbreakers dir. Harmony Korine (2012); The Rules of Attraction by Brett Easton Ellis (1987)

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (1952); Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet (1990); School Daze dir. Spike Lee (1998)

Animal House dir. John Landis (1978); Geronimo Rex by Barry Hannah (1972); Andrew W.K.’s I Get Wet (2001)

Indecision by Benjamin Kunkel (2005) or Flatscreen by Adam Wilson (2012); Andrew Bird’s Armchair Apocrypha (2007); The Graduate dir. Mike Nichols (1967)

Suspiria dir. Dario Argento (1977); The Lecturer’s Tale by James Hynes (2001); Suspiria film soundtrack (1977)

Cat Power’s Moon Pix (1998); The Squid & The Whale dir. Noah Baumbach (2005); Stoner by John Williams (1965)

Previous MEDIA FRANKENSTEINS:

IN ONE MONTH: As I Lay Dying