interviews

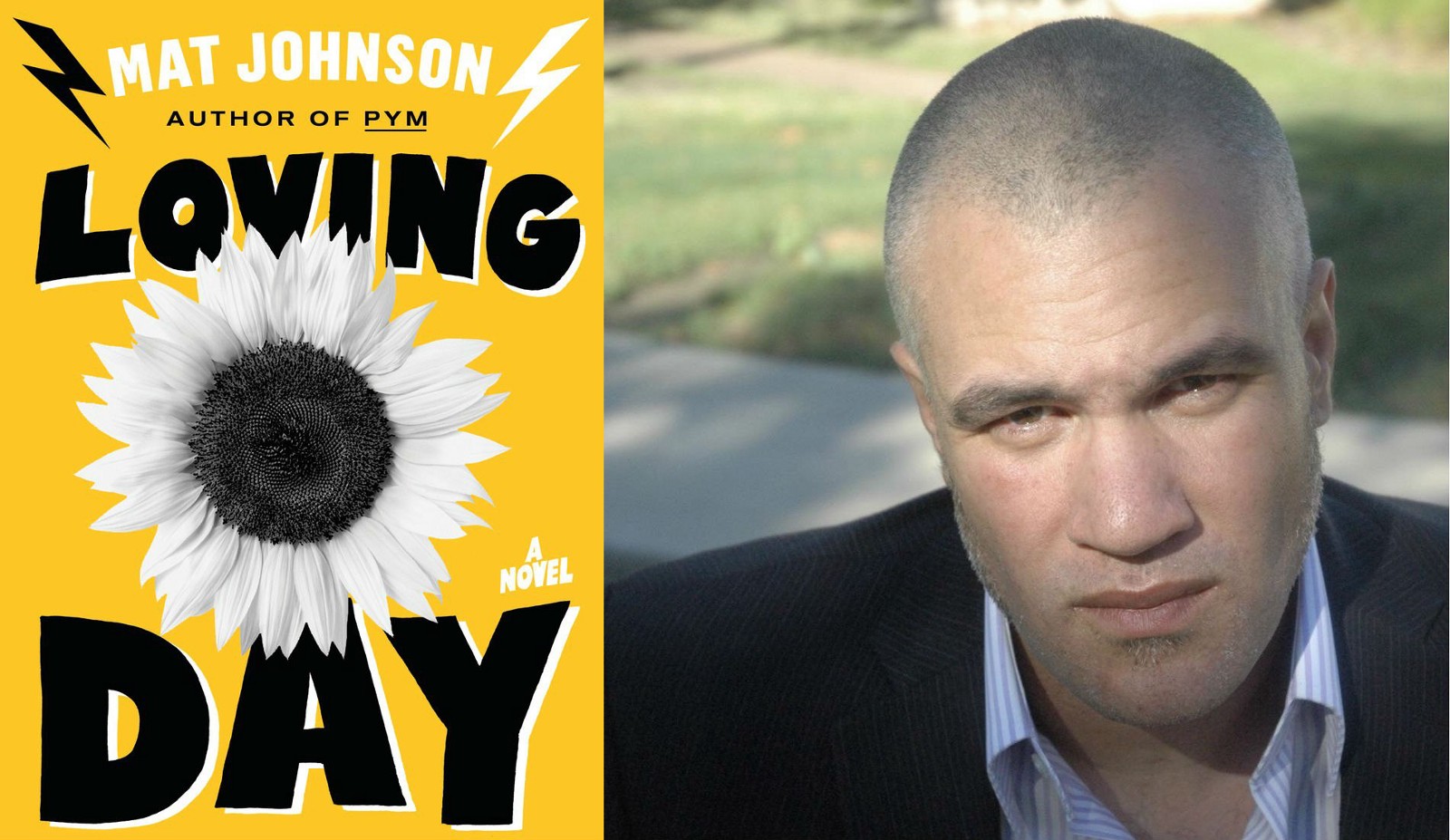

Pitching Chaos, an interview with Mat Johnson, author of Loving Day

This week marks the release of Loving Day, the new novel from Mat Johnson, author of Pym, Drop, Hunting in Harlem, Incognegro, and others. Johnson and I spoke last week on Skype. I caught him in his car, heading home from a school tour, and we continued our chat as he walked across the campus of the University of Houston, where he’s a faculty member in the creative writing program. Johnson has an energetic, incisive way of speaking. He works historical analysis, social observation, literary critique and wicked one-liners into the span of a sentence or two, always with the kind of conversational ease that makes you feel like he’s been mulling things over for a while and you were just the person he was hoping to see. We talked about race and culture in Philadelphia, prioritizing entertainment in literature, fatherhood, the book community on Twitter, and “the idea of being a straight male interacting with the feminine” (yes — sex — but other stuff, too…).

Dwyer Murphy: Over the course of your career, you’ve shifted between novels, graphic novels, comics, and non-fiction. With Loving Day, you’re back to the novel. How do you decide which medium to work with? Does the story dictate the format?

Mat Johnson: Usually it starts with the idea. I would say I’m a novelist first, but if the idea doesn’t fit into a novel, then I look for other ways to tell it. The graphic novel is kind of my way of doing a short story. I don’t usually write short stories, but I’ve found that pieces that are about the length of a story and have a strong visual aspect tend to work really well as graphic novels, so that’s how I’ll tell those particular stories.

DM: So with a Loving Day, you knew from the beginning you had a novel?

MJ: I did. I started with a line: “In the ghetto there is a mansion and it is my father’s house.” I’ve heard people talk about starting with a line and not knowing where it would lead, and I wanted to try that. So I had that line, and I started writing about Germantown, where I grew up. Germantown is this former colonial suburb in North Philly, a country estate that ended up becoming a black working class / middle class liberal neighborhood in the 1960’s, after the white flight. I realized that this neighborhood — with its big European architecture and a predominantly black population — had stuck with me not just because it was my own place, but because it was a representation of my own self. It’s a mixture of African American and European American culture. The first chapter — talking about the house — is pretty much the first thing I wrote. And once I wrote that, I started to realize what the story was about.

DM: It sounds like your first priority is the story, as opposed to, say, the voice. That’s not necessarily the case for a lot of contemporary literary fiction.

MJ: The story is very important to me. I want to entertain. I want to do something more, but I want to entertain, too. That’s one of the reasons I love 19th century literature — Frankenstein, Mark Twain, Henry James, Melville. The best of it entertains and does more. That carried into the 20th century, too, but then somewhere in the 1970s there was a kind of split. It’s funny, if you look at the history of the Pulitzer, before the 1970s, many of the prizewinners were also well read. But then there was this odd shift in the 1970s — a division started growing. Literature wasn’t so interested in entertaining anymore. I see it as a professor, too. I read a lot of manuscripts and books whose primary concern is showing the world that the author is a genius, and there’s no real thought given to entertainment.

If prose is to continue to be vibrant, it has to entertain as well as do other interesting things.

If prose is to continue to be vibrant, it has to entertain as well as do other interesting things. That’s what you see television doing — Mad Men and Breaking Bad and shows like those. The work is brilliant and it makes you think about the world. There are scenes from Breaking Bad that I saw four years ago and I’m still thinking about them now. So what I’m looking at with literature is to reproduce that trend — to have work that’s compelling and interesting and fun, but also something more.

DM: While we’re talking about entertainment, I’ll say that I was struck — reading reviews and reader commentary on your older work — by how surprised people seem to be, finding genuine, intentional humor in literary fiction. We don’t really know how to approach that kind of writing, do we? Americans, I mean. The British have it somewhat figured out — probably lots of other cultures, too, but the British come to mind — they love the stuff.

MJ: We really do have this notion with literature that we’re eating our vegetables. If we enjoy it too much, something must be wrong. You see it with our books and with our readings. Oh my God do you see at the readings. People come and don’t expect to be entertained. They don’t expect to laugh. That’s not the goal. And it’s not the writers’ goal, either. Writers are there to show people what geniuses they are. But that’s a larger American art thing. The point is not the work itself. The point is the artist. The point of Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup cans is as much Warhol as the paintings. I think it’s fucking disastrous. If people don’t enjoy themselves, they’re not gonna keeping coming out.

DM: You started telling me a little about Germantown and what it was like when you were growing up. What’s it like now? It’s different, I assume.

It forced me into this dichotomy of blackness and whiteness that I’ve been rejecting ever since.

MJ: The neighborhood in this book, to be honest, is the place of my imagination. It’s an older version. There was diversity in Philly, but not real diversity, the kind you have in a place like Houston, where I live now, where there were all these immigrant groups have come in waves. In Philly, it was black and white, for the most part. There were small Puerto Rican and Filipino populations, but otherwise it was black and white. That affected the way I saw the world. It forced me into this dichotomy of blackness and whiteness that I’ve been rejecting ever since. In some ways it was a more extreme version of what happened in the country when I was growing up.

But the truth is, the Germantown that exists now is a bit different. I tried to hit on that in the book through the narrator’s daughter, who tells her father this is not the neighborhood he thinks. His version is frozen in 1993. Now, Germantown is starting to gentrify like a lot of places. It’s actually a really great neighborhood. My wife and I thought about moving back there for a while, until we settled in Houston.

DM: Your narrator starts the book with this dichotomy — black and white — and something akin to the one-drop rule — if you have a black parent or grandparent or ancestor, you’re black. I’m wondering, how does that worldview get imposed? Does it come from both ends of the community?

MJ: That was the way most people in America looked at blackness up until the late 1980’s. Philly was more extreme. It had this very low immigration rate, so the historic population is what remained. Actually the book I’m working on now is set in the 1800s and, ethnically it’s pretty much the same. So that was the understanding — if you had a black parent, you were black. It didn’t matter how light skinned you were. You were black. One thing to remember is that the African-American community is not ethnically monolithic. The average African-American has 25% European heritage. So it’s a mixed race community. Historically, when there was a child born between a white person and a black person, the child was automatically African-American, because the child fit into that larger mixed race community. (Often, those children were born into slavery, and there was also a denial about the father being white, which supported that same cultural cutoff.) So that system continued — you’re black or you’re white, even though racial purity is, of course, a false notion. We’re all mixed at some point.

DM: Loving v. Virginia (the Supreme Court’s decision striking down anti-miscegenation laws, referenced in the title of your book) didn’t come until 1967, shortly before you were born. Growing up, were you aware of the history of discrimination — legal and cultural — against those marriages?

MJ: Pennsylvania hadn’t had those laws in a long time, but I was aware that there were people who were upset about my parents being married. I was aware that we went out and got funny looks. And it was for different reasons. It wasn’t a blanket reaction against interracial marriages. People in the black community looked at my Mom and thought she was rejecting blackness and thought that’s why she had a white husband. People in the white community looked at my dad like he was crazy or a mad liberal trying to prove a point. So it was more of a cultural thing.

When I was a kid, I didn’t hear the word biracial. It wasn’t until I went to college in 1990 that biracial identity hit the mainstream. It started with the census and built from there. And the push was so dramatic and so overnight, that younger people now don’t even remember the time before. It’ll be the same way with gay marriage. In ten years, kids will think it was absurd that there was a time when gay people couldn’t be married.

DM: Is that how you think of yourself now? Biracial?

The thing is, the words we use to talk about race are not really sufficient.

MJ: The thing is, the words we use to talk about race are not really sufficient. We have black as a legal term defining your race, and then black as a reference to your ethnicity. My parents divorced when I was about four. I grew up with my black mother in a black neighborhood. I had access to European-American identity every other weekend through my father, but I grew up with my Mom in my neighborhood, so my normative place was an African-American identity. The conflict came up because I don’t look African-American. I have a ton of mixed friends who had similar experience, where they grew up in the black community, but they look black, so being mixed isn’t an issue at all. They don’t even like to talk about it, because it takes away from their blackness. For me, the conflict was in how I looked. That’s often the issue — how you identify and how you’re perceived by the world. I honestly wouldn’t be bothering about this except that it’s something that comes up for me all the time.

DM: I’ve read about you using more provocative terms — mulatto, octaroon — to describe yourself.

MJ: Octaroon was a joke. Mulatto wasn’t. I’ve got a piece coming out for Buzzfeed about the word mulatto. I think that’s a good word to start using more often. People don’t like the word, but they can’t point to why, or they think it’s a reference to a mule. But the word is actually an Arabic word referencing people of mixed heritage. It predates the word for mule. Historically, it’s the word we used for people of mixed race in this country. And the thing about words like mixed and biracial is that they’re completely vague. They don’t make much sense. Most black and white people who consider themselves biracial, their race is listed legally and socially as black. Plus bi- doesn’t work because there are other races mixed in there, too. Part of the thing that worries me about the biracial movement is that it can be ahistoric. And as I said the vast majority of African-Americans are of mixed racial descent. So by the definitions they’re using, every African-American is pretty much biracial. It would be a miracle if they did a test and there weren’t some European poking in. In my view, mulatto acknowledges that there’s a larger history. And for me, the black and white mixed experience is part of my African-American experience. I still consider myself African-American, just mixed African-American. It’s like, if you have a Dad whose Irish, you’d be Irish, and nobody would debate that just because your Mom was Italian. But for African-Americans, we have these rigid ways of looking at the issue. We’ve inherited these preconceived notions.

DM: When your narrator, Warren, goes to work at a charter school — the mélange center for multiracial life — he learns about different mixed race communities throughout American history. Is that history something you’ve been interested in researching?

MJ: It was actually my wife who started researching them. In these enclaves, kids grew up knowing their fathers and identifying with both their fathers’ and their mothers’ cultures. And because of that, they came up with different identities. Throughout the Americas, you have people who are a mixture of African, European and Native-American heritage. The difference biologically is just the percentage. That’s from here down to Brazil. But the way people identify in these places is cultural. You have people who identify as black here in the States, and they could go to Jamaica and be considered white. I remember, during my mandatory Bob Marley phase, hearing Marley talk about Michael Manley as the white politician, and I saw a picture of Manley and I thought, Oh my God, he’s black. It was the same thing when I lived in West Africa. In Ghana, a cab driver told me they had a white president, and he meant JJ Rawlings. Over there, the norm is black, and any deviation becomes white. Over here, it’s the opposite — the norm is white, and any deviation is black. That’s a complicated issue. As soon as I put that stuff into my book, I thought, there goes my overseas sales — these identities are not going to make any sense outside the US.

DM: I know you’re joking, at least in part, but do you feel like publishers have trouble figuring out how to market your books, because of these identity issues? The book industry still relies on a lot on old categories — especially the identity of the author — and I wonder if that gives you a hard time.

MJ: First let me say I’m really happy somebody is publishing me. I don’t want to bite the hand that feeds me. And my editor Chris Jackson is one of the best in publishing and one of the few black editors in publishing. But it’s weird, when I did my second book, Hunting in Harlem, it was a satire with an oddball humor and some intense moments and absurdity, and the book did nothing. Then when Pym came out, it did well, and all the reviews acted like that was a new thing, and I was thinking I’ve been out here selling these same tacos for years, and nobody took a bite. But part of that is what we were talking about before — humor in general is undervalued. One thing that surprised me is that I got a lot of Vonnegut comparisons. I hadn’t actually read Vonnegut, so I went and read everything he did. My inspiration was Joseph Heller and Catch-22. And if you look at Vonnegut and Heller, they didn’t get a lot of accolades. People care about them long term, but this isn’t a country that gets lots of satire. I mean, Pym was on a bunch of best-of lists at the end of the year, but two or three felt the need to mention ‘books like this don’t usually get named to these lists.’

I know what I do: I throw knuckle balls. I’m not a fastball pitcher, I’m not a finesse pitcher. I know how to throw chaos in a way that has a higher than normal percentage of landing.

My work just doesn’t fit in that well in the literary discussion. I think my strength as a writer is also my weakness. The work is different than a lot of stuff that’s being done. I don’t mean that as a humblebrag. I’m off on my own tangent. Every time I try to write a non-offensive bestseller — because seriously, I could use some of that money — I just can’t do it. I start a project and it always gets weird. The book wants to go in its own direction, and if I don’t follow, the book will suck. So I follow it — I write about crackheads who are ghosts and I know I can say goodbye to Oprah’s book club. It’s never a conscious decision. It’s so hard to write a book that’s just basically good, not even great, just good enough. I just can’t do it if I’m tying one arm behind my back. I’m not good enough to be mediocre. I’m good enough to roll the dice. My projects have been hit-or-miss. I put myself out there, in an uncomfortable position on the page, then I have a panic attack for three or four years trying to pull it off, and I just really hope the book doesn’t suck. (Pym took about nine years to write. Loving Day took eight, believe it or not.) I know what I do: I throw knuckle balls. I’m not a fastball pitcher, I’m not a finesse pitcher. I know how to throw chaos in a way that has a higher than normal percentage of landing.

DM: You were in on Twitter pretty early, at least for the book community. And you’ve been pretty active over the years. It seems like Twitter has helped your career, and I was wondering if that was luck or design or something else.

MJ: I was kind of stuck between the old publishing promotion model and the new. Honestly, Twitter worked way better for me than anything had before. I’d never gotten big ad budgets or a big publisher push, so Twitter was an interesting way to work around the publishing industry. I found so many people there. That was completely unexpected. I got on Twitter just to goof off. It was 2008, and a few of my friends were on, and it was just an intimate little cocktail party. Later it turned into something dramatically different. I was able to kind of rise with the tide, which helped my book — Pym. It was a strange experience: Pym came out and people were suddenly paying attention. I was a little freaked out. I was used to my books failing.

DM: Are you still feeling positive about Twitter? Any personal backlash?

MJ: I can’t stand it right now. All these social networks ultimately become doomed by the fact that they serve humanity. Everything you hate about people, that’s what happens on the site. The same thing happened with Facebook. In happened in part because Twitter just got so big, and in part because of tweaks to the site, like adding the retweet function. It’s become a broadcast yelling machine. It seems like there’s a competition to see who can be the most righteous. I’m just not enjoying it much.

DM: Fatherhood seems like a relatively new subject for you, at least as a focus. I imagine the racial themes will get more attention with this book, but it’s also a coming-of-age story that looks at relationships between fathers and kids.

MJ: It’s funny. The racial stuff in the end becomes just the setting. Ultimately it’s a story about the transition from being a guy to being a man, and about learning to become a father. That fatherhood relationship is really at the center of the book.

You still see a lot of old school macho bullshit in contemporary literary fiction.

I also wanted to deal with the idea of being a straight male interacting with the feminine. That’s been done, but honestly I don’t like the way it’s done. You still see a lot of old school macho bullshit in contemporary literary fiction. You see it perpetrated by people I know in person are complete fucking wimps. They’re compensating for their minor castration by putting this male bravado on the page.

DM: In terms of interacting with the feminine as a straight male, this novel also delves into sex. I’m not sure if that’s a departure, but it seems notable. American literary fiction tends to steer clear of sex these days.

MJ: Sex is one of the scariest things to write about. It’s so easy to have it fall into the pornographic or into the absurd. The safest method is to make sex seem absurd. That lets you and the reader off the hook. But most sex is not absurd. And it’s not pornographic. Most is in the middle — there’s absurdity and difficulty and passion. That’s really hard to nail. I did some in Loving Day, and I’d like to explore it more, because it’s such a central part of our lives. It’s interesting — I was looking at that worst sex award the other day. People were picking on Franzen. But that shit is hard. Part of it is the insanely problematic history of hetero male existence and sexual dominance and rape and what we now call rape culture. It’s just got all that baggage. But part of our artistic job is to figure that stuff out, to add nuance and understanding. That’s what I’m trying to do. I mean, I had sex once, and it was fantastic, so I figure I’ll just write about that for a while and see what happens.