interviews

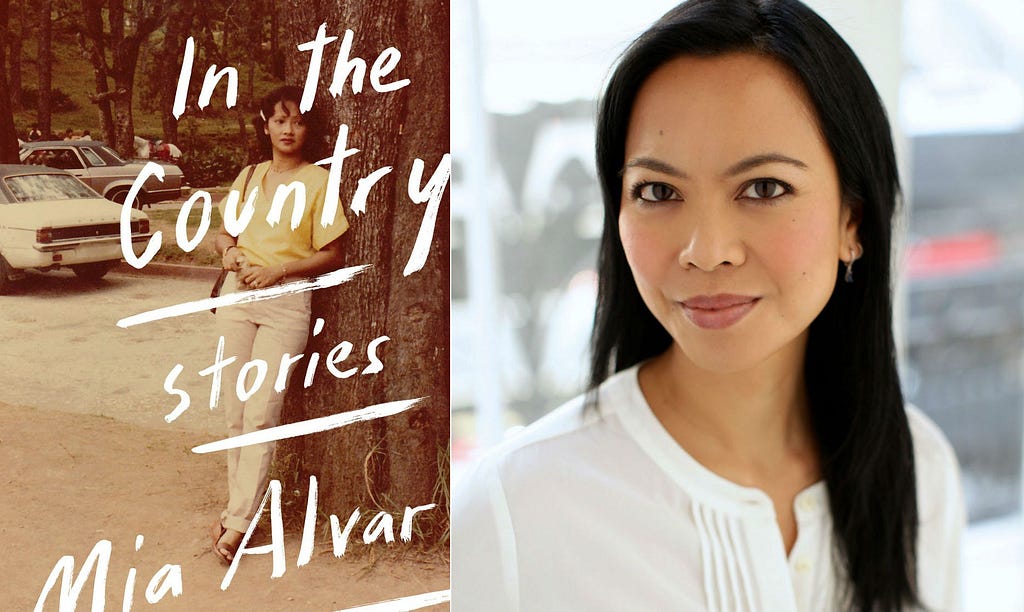

What’s Lost and What’s Gained, a conversation with Mia Alvar, author of In The Country

by Jonathan Lee

This week marks the release of In The Country, Mia Alvar’s debut book, a rich and varied collection of short stories about the lives of men and women within the Philippine diaspora.

Alvar was born in the Philippines and lived there until she was six, after which her family moved to Bahrain and eventually to New York. As a writer, she has the ability to capture that peculiar blend of excitement and pain that comes with uprooting oneself from a specific place or idea. Many of the stories in the book deal with literal border-crossings, but what binds the collection together more broadly is a sense of creative displacement. This is a book in which characters are addicted to dreaming, embellishing, or outright lying, and in one story a young woman even goes so far as to become that most heinous of fraudsters: a fiction writer. “I never could get used to the ‘withdrawal,’” the character admits. “The rude comedown from having lived so much inside a story it felt real.”

There’s a similar comedown to be experienced upon closing In The Country, a vivid debut that deserves to catch the interest of prize committees. I sat down with Alvar earlier this month to discuss it.

Jonathan Lee: Talk me through the early stages of construction. What’s your typical process for beginning to pull a story together?

Mia Alvar: If I have an idea rattling around, the only way I can start writing about it is to convince myself that I’m not. Writing for me is so much about the reading and the thinking beforehand — I’ll read all the books I can get my hands on about a subject, or that use a device or strategy I want to try (like the first-person plural point of view, when I was writing “Shadow Families”). I keep a notebook nearby, to jot things down that occur to me as I’m reading, but I tell myself it’s research, not writing, to keep from getting spooked. I could just do that — read and jot down notes — forever. But eventually my agent or editor will say, “How’s it going, that thing you were going to show me?” So I panic and type up my notes into something that looks like a story. That stage is a nightmare, trying to bully a beginning, middle, and end out of material that’s still a huge muddle. But the pressure is useful, too. When a deadline’s looming I’ll stop lying to myself and write ten hours a day, or whatever it takes, to put something together, even if it turns out to be all wrong.

Lee: When you look back through your notebooks and start typing things up, do you find yourself surprised by what’s in there?

Alvar: Definitely. That reading/thinking/jotting stage always feels so productive, and I’m always so happy in this belief that I’m generating idea after brand-new idea. But then I’ll look back to find pages upon pages of essentially the same sentence written hundreds of times, in only slightly different ways. And somehow it’s this huge shock to me every single time.

Lee: What are the kind of things you’re looking for in a sentence, and what are the things you’re looking to throw away as you revise?

I want things to feel clean and conversational, a sense that someone’s telling this story aloud to a friend or relative.

Alvar: Although I’m a maximalist in so many ways — my “short” stories all push that 25- to 35-page limit, much longer than most literary journals are willing to read — I’m always, at the word level, looking for less. If there’s a three-syllable word that I can swap out for one syllable, I’ll do that. I want things to feel clean and conversational, a sense that someone’s telling this story aloud to a friend or relative. When I get stuck I try to think, “Okay, but how would I say this to someone sitting across the table?” The idea of translation also helps: most Filipinos speak English, but sometimes if a sentence doesn’t seem to be landing right, I’ll ask myself how a narrator might say it in Tagalog, and translate that in the most direct and literal way back to English. That often points me to a clearer, more precise, and simpler expression.

Lee: As I read “A Contract Overseas”, I found myself wondering whether you identify much with the narrator of that story — her feeling of seeking out the right kinds of stories to tell, and questioning the impulses behind that desire to tell stories. She worries that her brother, who’s gone abroad in pursuit of financial security, is living the eventful life — the one better-suited to fiction. I think anyone who writes fiction has probably had at least one of those moments — a moment spent wondering whether to shake up their life in some way just to see what new material might drop to the floor.

Alvar: “A Contract Overseas” definitely felt personal to me. The narrator’s instinct to write about her brother and his compatriots in Saudi gave me a space to work out my own questions about why I was writing this book about expat families and the Philippine diaspora — and, more largely, what fiction is for. Are my stories purely a tribute? I don’t think so. Is fiction about wish fulfillment? Well, the narrator of “Contract” does sort of wind up there, writing as a way to keep a loved one close. Is it about giving voice to men and women who aren’t always represented in fiction? Or is it just about following the subjects and characters that I find most compelling, and trying to entertain the reader in the process? I think it’s all and not quite any of the above.

Lee: The first story I read of yours was “The Kontrabida”, back when it appeared in One Story in, I think, the summer of 2012. I’d just moved to New York from the UK and I bought up a stack of literary journals, including One Story. “The Kontrabida” really stood out to me, and I see that it stands as the first story in the collection too. Why did it feel right to put it first?

Alvar: That story is the oldest one in the book. I think it sets up a lot of what the other stories touch on: migration, our ties to the past, the stories we tell about our families in public and the things that happen behind closed doors, the strange places our good intentions sometimes take us. The memories that inspired that story were also the same ones that got me writing fiction, and thinking about a short story collection, in the first place. In the late ’90s I traveled to the Philippines, much like Steve did, because of a death in the family. All these rituals around death and dying that surely had been around throughout my childhood struck me, after being away for so long, as completely new and alien when I returned. Araneta Avenue, for instance, which in my mind I can’t avoid thinking of as the “death district,” was just one of the sights that completely arrested and stayed with me: a long row of storefronts, servicing every funeral-related need from headstones to flowers to cremation.

Lee: Is that a typical process for you, in creating a story — that you’ll take a real moment from your own life and build outwards from that, moving from experience into imagination?

Alvar: Sure, but imagination is the far bigger component. One thing that’s troubled me a bit in some of the pre-pub writeups about the book is the notion of “armchair tourism.” The idea that my book is a good one to read if you’d like to visit the Philippines without leaving Brooklyn? I get it, but still…

Lee: Does that idea of “armchair tourism” feel distasteful to you?

As far as I’m concerned the Manila and New York and Bahrain in my book are imaginary.

Alvar: Not distasteful; I’m just afraid my book isn’t the best vehicle for it. I’m not that interested in factual or geographical accuracy at all, to be honest. As far as I’m concerned the Manila and New York and Bahrain in my book are imaginary. They have a real-life counterpart, but so many features have been twisted and reinvented or added or erased to suit the story. So I really hope that people don’t read the book and think, “Oh, that’s what an overseas contractor who comes home from Saudi Arabia does!” Or: “That’s where I can go to get a meal.” I’ve made up rituals that don’t exist in the lives of people who don’t exist. In “Old Girl” I talk about a chain of Filipino expat households in Boston that calls itself “Manilachusetts.” That’s not really a thing. But it could be, and that’s enough for me, in fiction. I’m much more interested from a craft perspective about what makes a story work than how faithful the details are to real life.

Lee: Let’s talk about “Esmeralda”, a story that focuses on a woman who works as a night cleaner in the World Trade Center. How did that story come together, and why do you think that particular material drew you in?

Alvar: That story came together accidentally — though it was a very slow accident. I knew I wanted to write about a woman who cleans for a living, who connects with one of her clients or customers in a personal way. But I had her in all sorts of settings — on the Upper East Side, cleaning fancy apartments, things like that. The story wasn’t coming together at all. I workshopped those early drafts in grad school, and was getting a lot of negative feedback.

Lee: I feel like stories told in the second person often stir up the strongest opinions in that kind of workshop environment.

Alvar: Yes, totally. There’s this paradox where the second person seems like it should connect the reader more closely to a character’s perspective, but so often the opposite seems to happen. People really resist identifying with someone if they’re being told to.

Lee: It can feel like a pushy form of narration sometimes. You do this, you do that. There’s a heavy imperative mood to second person stories sometimes, isn’t there? I think readers can feel like the author is eyeballing them and doing a lot of passive aggressive pointing or chest-poking …

Alvar: And I did try rewriting “Esmeralda” in the third person, but then changed it back. I decided I didn’t mind having an imperative, slightly more aggressive relationship with the reader in that particular story. I was happy to point and insist that “you” imagine yourself into Esmeralda’s life, to risk refusal on the reader’s part. It seemed like a useful way to call attention to both the necessity and the difficulty of truly identifying with someone you don’t know.,

…I would arrive just as the finance guys in their suits were leaving. And I’d work into the night, when cleaners came to mop the floors and take out the trash.

Still, the story wasn’t working on other levels and I was about to give up. And then I took a residency with the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, where artists and writers take up studio space in vacant corporate offices donated by corporations. I was working steps away from where 1 World Trade Center was being built, where the 9/11 memorial and museum had just opened. And of course I kept writerly hours, so my colleagues and I would arrive just as the finance guys in their suits were leaving. And I’d work into the night, when cleaners came to mop the floors and take out the trash. It came to me that maybe Esmeralda cleaned offices instead of apartments, her shift starting after most people had left their desks for the day. And because it’s nearly impossible to work in that neighborhood without thinking of 9/11 all the time, I found myself wondering, what if she didn’t just clean offices in a building but in one of the buildings? It occurred to me that if she did, she wouldn’t have been there in the morning when the towers were hit, but if she’d made friends with someone who overlapped with her shift when he was working late, he might be. So from there the piece sort of evolved into a story about Esmeralda working in the World Trade Center and meeting John, despite my huge fear of writing about that day. I told myself it was an experiment and I didn’t need to show it to anyone when I was done.

Lee: Did writing and reading about the events of September 11th become a way into other things you wanted to explore in the collection?

Alvar: Certainly a way into things I wanted to explore in this story specifically. Back when I had chosen the name Esmeralda, early on, I wanted New York City — its landscape, buildings and neighborhoods — to play a prominent role in her story, the way Paris and its architecture does for the Esmeralda of The Hunchback of Notre Dame. 9/11 gave me a really obvious context for that kind of hyperawareness of the city, and it gave the story a reason to be a kind of love song to New York. And I was glad to explore, through this connection between Esmeralda and John, the flip side of all my migrant narratives about alienation and estrangement: the fact that sometimes unlikely connections are forged between strangers thrown together in a strange place. And that’s definitely a narrative that comes up — forced connections and unlikely intimacies between strangers, helping each other or sticking together because they had no other choice — throughout the 9/11 archives and testimonies I was reading at that time.

Lee: I was reading a Paris Review interview this morning between Mona Simpson and Hillary Mantel. At one point Mona Simpson said something that I think relates to your work too: that “the majority of human history is lost”. It seems several of your stories show a preoccupation with the gap between the official versions of things and the lost or distorted truths underneath.

…that tension between the histories of record and the messier private dramas people contend with every day…

Alvar: I’m obsessed with that gap. When I think about what my book is really about, that tension between the histories of record and the messier private dramas people contend with every day feels as central as the geographical settings and emigrant narratives. So many characters in the book are contending not only with that gap but also with how attractive the official version can be, how much simpler and easier it is to label people saints or heroes or villains than to deal with the messy particulars.

Lee: There are lots of moments in the collection when deliberate deceptions occur, but it seems like you have a great interest in exploring moments of innocent misconception and misunderstanding, too. Often that seems to relate back to spoken language. There are some great moments of mishearing.

Alvar: Which story are you thinking of?

Lee: There’s a moment in “Old Girl” I remember where a man has been badly hurt. Through his pain he manages to explain the cause his wife, and she thinks he’s saying “black guys”. In reality, he’s saying “black ice”. An accident becomes an assault, and an act of God becomes an act of racial violence — all through a simple mishearing, the fact of people not listening hard enough.

Alvar: I later discovered that Key and Peele had done a joke about that! Devastating. My final edits had already gone in. But no, I definitely had fun playing with misunderstandings throughout the book, and I have to admit that offered some relief at times when the book’s subject matter got a little heavy. I had to find ways to be light-hearted. Those mishearings and confusions happen in real life all the time, and throughout the book, they became a way to talk about identity in ways that are both playful and problematic.

Lee: Can you think of an example of that?

Alvar: In “The Miracle Worker” the Minnie character approaches Sally by asking her, in Tagalog, why she looks familiar: whose maid was she? Sally makes light of it, as most women in my family who have had this experience would; that story of being mistaken for the Filipina maid or nanny is not an uncommon one. And someone pointed out to me recently that they appreciated those moments in “Legends Of The White Lady” when no one knows where Alice is from, mistakenly tracing her brand of all-American blondness to Kentucky or Texas in a kind of reversal of the experience minorities have all the time, and the guessing games that people are obsessed with playing when it comes to pinning down “what” you are.

Lee: There’s also this sense in the book that people don’t live one life — they can be different versions of themselves at different times.

Alvar: Yes, and transnational migration obviously dramatizes that idea — you literally leave your old life behind, in some cases adopting completely different ways of speaking and looking and being in the new world. One of my favorite writers is Joan Silber, who writes so beautifully about the passage of time and how we can sometimes barely recognize the younger version of ourselves. And yet that younger version — the young Milagros of “In the Country,” for instance, when she’s organizing a union and going on strike and meeting Jim for the first time — probably can’t imagine how radically different her life will look in the future. As with leaving home, I’m interested in both what’s lost and what’s gained in that transition.