interviews

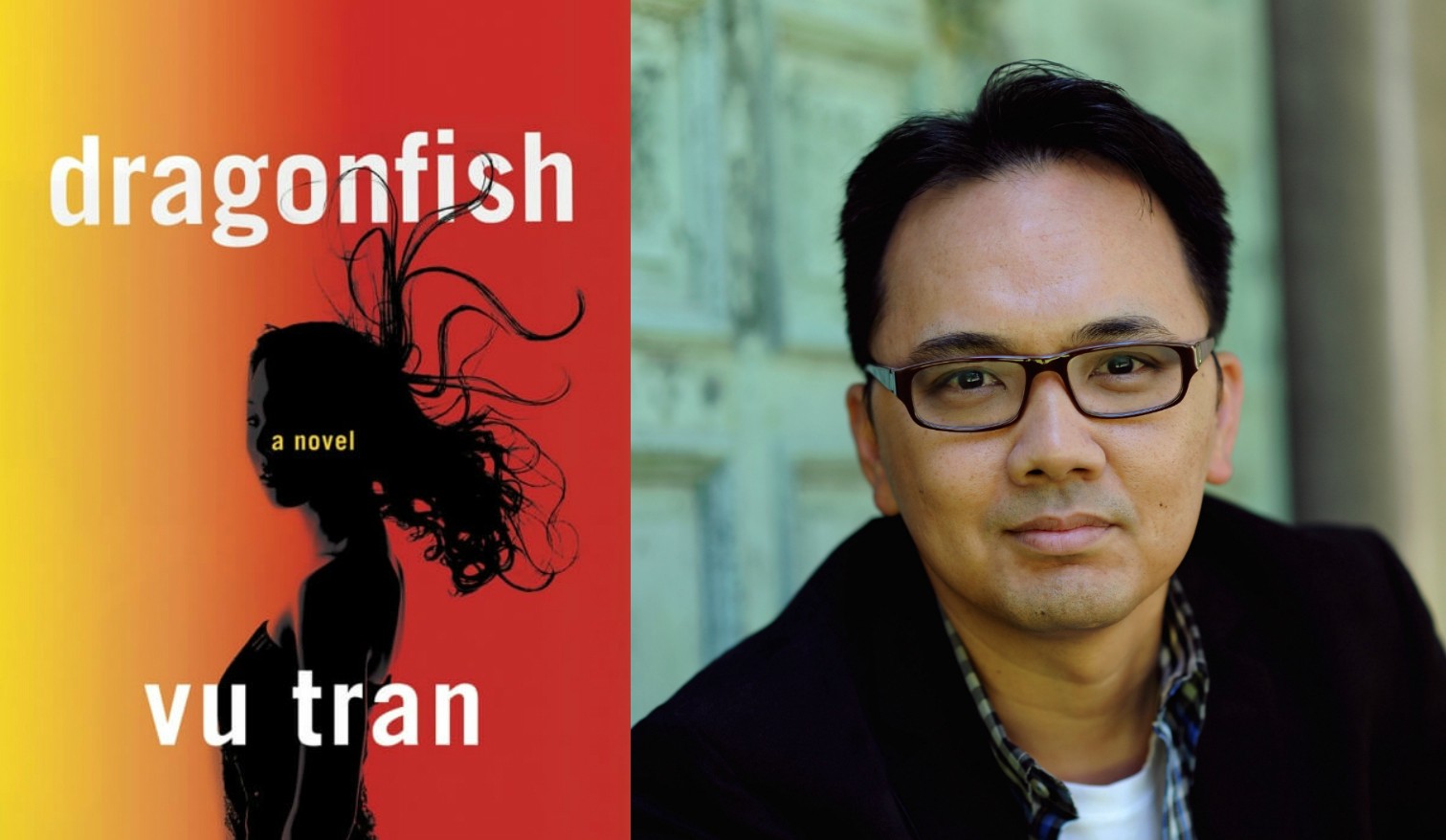

A Convincing And Compelling World: An Interview With Vu Tran, Author of Dragonfish

Vu Tran’s debut novel Dragonfish (W.W. Norton & Co. 2015) is more than a crime novel. It’s a story of displaced Vietnamese refugees who fled after the fall of Saigon and ended up in Las Vegas. When Robert, a white cop living in Oakland, is visited by two Vietnamese gangsters and ordered to Vegas to help them find Robert’s ex-wife, Suzy, he goes. Sonny, their boss and the book’s “villain”, is also her new husband. Through letters Suzy left behind, the reader learns of the ghosts that still linger from her past and the reasons she was never Sonny’s or Robert’s to lose.

Tran was the Fiction Fellow assigned to my workshop (led by Helen Schulman) at the 2015 Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. He also teaches creative writing at the University of Chicago. Along with his abilities on the page and in the classroom, I can attest that Tran also manages easily on a dance floor. See: The Worm. I saw him again weeks later on the Los Angeles stop of his current book tour, but it wasn’t until the next day, when he was already parked in a rental car four miles from the Black Mountain Institute at UNLV, where he’d earned his PhD in literature, that I had the opportunity to ask him a few questions about Dragonfish.

Andrea Arnold: I loved this novel and how smooth your writing is. I finished it in a few hours. I had to find out what the hell happened to Suzy. How did you come to the story?

Vu Tran: Jarret Keene, a writer in Vegas, asked me to write a crime story for an anthology he was editing called Las Vegas Noir. My assignment was Chinatown. I’ve always loved the noir genre in literature and film, so I said yes, absolutely. I was also working on another book that was painfully going nowhere, so I was more than happy to put that aside. That’s how I came to write “This Or Any Desert.” I wrote it really fast and had a lot of fun doing it. Then it got into the 2009 Best American Mystery Stories, and since I was desperately looking for something else to write at the time, I thought maybe I should turn this short story into a novel. The characters still felt nascent to me, like there were layers to them that I hadn’t yet found, that I still wanted to excavate. They felt like the kind of characters that could flourish in a novel and open it up in exciting ways.

AA: I’ve heard you talk about your experience coming to the US as a refugee. Can you explain the journey your family took and how it led to the novel?

…we left on a small boat with ninety people…We spent over six days at sea, headed at first for Singapore until the captain got lost and we ended up in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. We were very lucky.

VT: I didn’t really find the novel until I reached into the backstory of one of the characters in “This Or Any Desert,” who talks about escaping Vietnam with his father by boat and being on a refugee island. That came from my own experience. When I expanded the short story and brought this same backstory to my protagonist, Suzy, it provided an emotional foundation for the rest of the novel, connecting the main characters to each other emotionally as well as literally. I was born in Vietnam in 1975, four months after Saigon fell and four months after my father, a captain in the South Vietnamese Air Force, fled the country. He had to leave the very day the communists took over Saigon and the South. He was going to take my mother, who was pregnant with me, and my sister, who was two at the time, but he ended up having to escape without us. For a year, my mother had no idea where he was, what had happened to him, or if he was even alive. She finally found out that he had settled in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where a Catholic priest had sponsored him. Five years later, in 1980, my mother bought passage for herself and my sister and me, and just like in the book we left on a small boat with ninety people. There was really only room for about twenty. We spent over six days at sea, headed at first for Singapore until the captain got lost and we ended up in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. We were very lucky. Thousands of Vietnamese were attacked by Thai pirates, drowned at sea, died of hunger and illness. I’m sure it was all terrifying and difficult for my mother at the time, but I’m always amazed by how lucky we were ultimately. The Malaysian and US government had established a refugee camp on Pulau Bidong, an island off the coast of Malaysia. We lived there for four months. Then my father sponsored us, and that was how I came to grow up Tulsa, Oklahoma. It’s where I met my dad for the first time and where I lived for twenty years.

AA: There are a lot of details about that island in Suzy’s letters. Did you remember all those details or did your mom fill in the gaps or did you have to look it up?

VT: I remember very little, only small details. Like the smell of the ocean. Or standing in the water up to my neck. I remember lying on thatch beds made of palm leaves and cardboard, which was how we slept at night in our huts. I also remember — and this is a weird detail — when you go to the bathroom you take a newspaper and squat under a palm tree. Everything else about the time I had to ask my mom or invent or research on my own.

AA: Was that experience something constantly talked about in your family or was it something purposely forgotten and avoided in conversation?

VT: My mom talked about it a lot when I was growing up and had a lot of stories, which I drew from for the book. I would call her all the time when I was writing and ask for more detailed accounts of everything. As a writer, you take some of those concrete facts and you run with them. You invent out of them. I’d say 99% of what’s in the book is invented, but their foundation is built on these facts from my life.

AA: Suzy’s letters are full of longing for Vietnam. Does your mom talk with the same type of longing when she tells you stories about Vietnam?

VT: My mom rarely spoke about it with melancholy or longing, at least not outwardly. She certainly missed Vietnam and her family, especially before she returned for the first time in 1992. We returned as a family twice in the late 90s, and she and my father have visited several times over the last decade, so maybe the melancholy has evolved over the years. I’m glad you ask this question because I haven’t thought enough about how my mom must have felt all these years, recounting this other life she had before we came here. It’s weird, but sometimes, as a writer, you value the material more than you value how that material is given to you, particularly by those who are very close to you. Even though the US is my mother’s home and she’s become used to the life she’s led here for 35 years, I imagine there will always be some melancholy in her for Vietnam. I don’t think you can ever shake the homeland, especially if you left it under such dramatic circumstances.

AA: For you, was it just super cool, exotic and fun to travel abroad, or did you feel a connection to Vietnam even then?

VT: When I first came back, yes, it was just really cool and exotic. I was twenty and hadn’t gone abroad until then. I was just an American traveling to a strange new place for the first time, even though it was the place of my birth. The experience was very fun and exciting for me, but I don’t think the emotional connection came until afterwards, when I got back to the States and had time to feel the impact of such an experience. I think the most significant thing was meeting — and I guess reuniting with — my extended family, who’d remained in Vietnam and had all these memories of me up to the time I was five. That reminded me that I’d actually had a life in Vietnam, even if I didn’t remember it, which gave me an emotional connection to my family and therefore to the country. That’s when I started writing about Vietnam, and writing about it solidified and deepened the connection.

AA: Is it typical in Vietnamese culture for people to believe in ghosts or were you simply using a noir trope?

You’re not just living for your immediate family; you’re living also for your extended and ancestral family.

VT: Ghosts are very much a part of many Asian cultures, whether you’re Buddhist or Christian or whatever. I was raised Catholic and taught not to believe in ghosts and demons, but my mother has always been a superstitious person, which is true of many Vietnamese. I don’t think you can escape that in the culture, especially when it’s been dominated for centuries by a Buddhist belief in the spirits of one’s ancestors, lingering in the reality of one’s present life. It’s one reason the family is so important in the culture, because of that connection to the past and to past lives. You’re not just living for your immediate family; you’re living also for your extended and ancestral family. American culture, it seems to me, is one of the least superstitious cultures in the world, which is why ghosts are usually the purview of pop culture instead of our everyday lives. Ghosts are alive in South American culture, in African culture, in European culture, but Americans generally don’t take the idea very seriously, and I’ve always thought this contributes to how the family is viewed here.

AA: So what was your research process like? Did you interview people in the Vietnamese community in Las Vegas?

VT: Not really. First of all, I’m a very lazy person. [Laughs] I try to do as little research as possible. Too much information can distract me from the true pulse and direction of a story. I also don’t think a book necessarily comes to life because of the concrete facts that come from hard research. It comes to life because of the emotional vibrancy and complexity of your characters, and that’s something that comes more from the imagination, personal experience, and observation. But of course, some research was necessary for Dragonfish, especially on the Vietnamese boat people and life in the refugee camps. So I did a lot of reading on that. I also talked a great deal to my parents, asking them as many questions as I could think of. For all the procedural, cop stuff in the crime narrative, I went to my sister and her boyfriend. They’re both police officers in Texas. She’s also a negotiator and he’s on the SWAT team. They were always at the ready with stories and information for me. But again, I didn’t want to clog my brain with extraneous material, so I was always looking for specific details and answers to very specific questions and scenarios.

AA: Were there any concerns about making Asian characters likable? Are you worried about stereotypes and being stereotyped? I’m thinking specifically about Happy’s dialogue and her affectations.

VT: That’s a good question. Happy was very difficult. The thing is, that’s how Vietnamese-Americans with a heavy accent speak. But the problem is that that accent, the Asian accent in general, especially on paper, can sound very cartoonish, and the scenes with Happy were serious scenes. So one of the difficulties of writing her was keeping her speech realistic while also making her sound serious without sounding cartoonish and making the scene unintentionally amusing.

AA: I thought you did a wonderful job, but there are Asian characters in my novel and I think if I did it that way someone would tell me I was being racist.

VT: [Laughs] I was concerned about that too, in many ways, but I also realized that focusing too much on that aspect could distract me from the more important question, which is whether the characters were convincing. The world you create in your fiction will only be convincing and compelling if the characters are convincing and compelling. A character who is cliché is cliché not because they’re too Asian or too whatever, but because they have no depth and aren’t convincing in the world you’ve created for them. I kept thinking that with my characters who were potentially stereotypical or maybe even offensive, like Happy or Sonny, that if I gave them depth and I made their behavior believable and utterly convincing and, most importantly, interesting, those concerns about cliché or racist representations would fall away. Hopefully they did.

AA: Were there any concerns about making Asian characters such bad guys

I don’t really care if my Vietnamese characters are “bad” or “immoral”. I only care about whether they’re believable and interesting.

VT: My editor posed this same question to me, not because it was an issue for me but because she was just curious how I would answer it. She asked me why the white protagonist is the good guy — the virtuous and heroic cop — and most of the Vietnamese men in the novel are gangsters and immoral characters. This becomes, I think, a question about likability as much as moral representation, and frankly I think that’s the wrong question to ask yourself while you’re writing. That’s how your characters become one-dimensional. I like the idea of readers constantly changing their minds about characters. That’s when you’re creating interesting people on the page. Sonny is the prototypical bad guy in a crime narrative. He commits violent acts and speaks in an aggressive way, so the reader is forced to think of him initially as a villain. But if you keep complicating a character like him, giving him more and more layers of depth, the reader will keep changing their mind about him. Think about the most interesting people in your life: they’re the kind of people you can’t fucking decide on. You can’t decide if you like or hate them, if you want to be friends or enemies with them. Those are usually the most interesting people you know, and those were the kinds of characters I wanted in the world of my book. So I don’t really care if my Vietnamese characters are “bad” or “immoral”. I only care about whether they’re believable and interesting.

AA: My favorite parts of the novel are Suzy’s letters. The writing is beautiful, emotional and full of longing. To me, it felt like Suzy probably had an MFA from Iowa! Can you speak to writing in the first person from a female perspective as a male author?

VT: [Laughs] First of all, that’s really funny. Thank you. I’m glad you like it. When I devised the letters that Suzy is writing to her daughter, I felt like I found the novel. And weirdly enough, I found that voice fairly quickly, and it was easy to maintain. I was obviously very aware that I was writing from a woman’s point of view, but it never felt difficult. I think when you understand what a character wants, what a character is afraid of, and what a character is confused by, that character will come alive on the page, even if you personally bear no similarities to them. They could be completely different from you — a different ethnicity, a different gender, a different age — but if you understand those three things about them on a deep level, you’ll find them. For example, I knew very early on that Suzy was a woman who regretted abandoning her child and at the same time knew that that was what she needed to do. She did not want to be a mother. But the emotional consequences of that act of abandonment never left her. Her motive in writing the letters is to explain her actions, not just to her daughter but also to herself, because they have always confused her. And I think that confusion has been a source of fear for her in the world, which she inevitably brings to her relationships — her marriage to Sonny and Robert, her relationships with other people. If I wrote her convincingly as a woman, it all comes out of me understanding those aspects of her character throughout my writing of her part of the novel.

AA: Vegas is an additional character in the novel. How long did you live in Las Vegas and did you begin writing the novel while you were still there?

There are few cities in the country that give you this moment, where you can see so many sides of it from one single view.

VT: When I was working on the novel, I had seven years’ worth of Vegas memories. I wrote the short story in 2008 and started turning it into a novel in 2009, which was when I sold it. Then I left in 2010 and didn’t return until after I finished the book four years later. I was very concerned when I first got to Chicago because I only had sixty pages and I kept worrying that I couldn’t write about Vegas well if I wasn’t there. And sometimes it did feel frustrating that I just couldn’t drive down to the Stratosphere and check on certain details. But I realize now that the distance was an advantage. I think a lot of writers will say this — that distance often allows you write with more insight and clarity about a place, a situation, or a people. The benefit for me in this novel was that I was not relying on concrete facts. I was relying on my emotional memory of the city. If I got Vegas right in Dragonfish, I got Vegas right emotionally. I could get all the concrete facts right about the Stratosphere Hotel, but I still might not be able to make that place come alive. But an emotional fact will. If you drive west of the Vegas Strip, on Highway 215 toward Summerlin, you’ll get to a point on the highway where you can look back and see the entire valley and the Strip right down the middle of it, and you can see the column of light that beams up from the Luxor like a guidepost in the sky. You feel like you can wrap your arms around the whole city and it kind of makes you feel safe. There are few cities in the country that give you this moment, where you can see so many sides of it from one single view. I also remember the mountains that surround the city, which are brown in the day, but at twilight, if you look at them at a certain angle, with palm trees in the foreground, the city almost feels like a tropical island. Things like that are unique to Vegas and can give you a more vivid sense of the city than concrete facts about the streets and casinos can.

AA: Did you write your way in until you found the story or did you outline the plot? Did you know the ending?

VT: I always had a vague direction of where I was going in the novel, but I didn’t know the ending until the last week before my deadline. This was different from how I worked on short stories. With stories, I always had an idea of the ending and the major plot points. The story wouldn’t always turn out as planned, but at least I had some idea of where I was going. With the novel, though, every time I tried to map out the specifics of the plot, I would slow down. I kept a word count every month and my lowest word counts were during the months I was trying to figure out the rest of the novel’s plot. So it ended up that I literally had to write the book word-by-word, sentence-by-sentence, scene-by-scene. I found that was the only way for me to find the story. That approach might change with my next novel. I don’t know. I have a feeling that each book will require a different approach.

AA: You earned your MFA from Iowa. Was there someone there you emulated?

VT: I really admired Marilynne Robinson. I’m honestly not sure how much I learned from her in workshop, but I learned a great deal from reading her novels, especially Housekeeping. Gilead was actually a big influence on Suzy’s letters. When I was writing the letters, I’d open up Gilead to a random page so that I could appropriate the voice of the narrator. I did learn a lot from my other workshop teachers: Chris Offutt, Ethan Canin, and Frank Conroy, who directed the program for 18 years. He passed away ten years ago. He probably changed me the most. I came to the workshop with a maximalist style. I wanted to be Faulkner. I wanted to be experimental. So I overwrote. My first workshop with Frank was a good one, and it was a story I was basically writing for him, which is never a good idea. And since that workshop went well, I thought, I’ll just be Vu now. And he totally destroyed me in my second workshop. It was the most important workshop I had at Iowa because I realized that I really had to work on my prose and be in control of it, whether I was writing in a spare style or an ornate style. I had to make sure that everything was meaningful and clear, that I wasn’t just hoping for meaning, that I was actually melding my form with my content. Frank taught me that. His lessons on language really burrowed into me as a writer. I am indebted to him for my sentences.

AA: What was the best advice an author ever gave you?

My best advice to any young writer is to be wary of all good advice, especially the kind that sounds universally and earth-shatteringly true.

VT: Dave Hickey at UNLV told me to “write fast.” [Laughs]. He meant it literally. Write intuitively and then go back and revise intellectually, deliberately. That’s actually the opposite of how I work, so I didn’t really listen to him there. But he also meant something else. What he really wanted me to do was know what I was saying and make sure I was saying it well, and just get to the interesting stuff and not be bogged down by less interesting concerns. He saw that extraneous things were slowing me down. Like my focus on making my language pretty. Or my focus on landscape details. He wanted me to cut all that shit out and write faster. So that, I think, was good advice. But honestly, I’m not sure if I’ve really gotten that much good advice over the years. My best advice to any young writer is to be wary of all good advice, especially the kind that sounds universally and earth-shatteringly true. Because there’s always an exception. Everyone writes differently just as everyone reads differently, so you don’t want to fall into the trap of following great advice to the point where you’re not seeing the exceptions to the rule, or the truth that might only be true for you.

AA: How does teaching affect your writing?

VT: I love teaching. It does affect my writing because I have the luxury at the University of Chicago of teaching what I want, and that inevitably becomes a way for me to work out things that are most on my mind. For example, for the last few years, I’ve been very interested in plot-driven narratives, in plot not only as a dramatic structure but also as a philosophical structure, a way of approaching our ideas in a work of fiction. So I taught a class on that and learned a great deal. I was also very interested in the love story last year because I was going through a breakup and had also just written a book about a relationship. So I taught a class on love stories, which was about, among many things, how we define what a love story is. And since I always learn a great deal from my students, it was particularly educational for me to observe how my students engaged with this topic. That’s when teaching really becomes an interesting part of my life — when it merges with my personal life and my artistic life.

AA: You said you wrote a first novel that you put in the proverbial drawer. Do you think you’ll go back to it and how did you decide that it was time to quit?

VT: When I was still working on that novel, a friend of mine asked me to describe it to her. She was German professor of American Literature. When I described it, she said, “No no, that’s sounds too much like every immigrant novel out there. Don’t write that.” And she was absolutely right! [Laughs] It was about a first-generation Vietnamese-American who travels to Vietnam for the first time to uncover a mystery about his family — a standard narrative, I realized. It’s weird how you fall into certain clichés without even reading the sources for those clichés. It’s like it’s in the literary ether and you just absorb it. Anyway, it was very much a first novel. The writing was good, I think, but I didn’t know what I was trying to say or where I was going. It’ll stay in the drawer.

AA: What are you working on next?

VT: I’m not sure. Two weeks ago I had an idea for another novel as I was driving on a long road trip, and I was so excited that I started singing. I’m not sure I want to talk about it yet though. I might also bring out my short story collection at some point, but I think I’d first have to rethink some of the stories. Maybe even toss out one or two. I’m such a different person and a different writer now.