Lit Mags

A Thousand Hundred Years

A story about the horror of finding someone you lost

AN INTRODUCTION BY BRIAN EVENSON

I first came across Michael Wehunt’s work a little less than two years ago, when we both appeared in Aickman’s Heirs, an anthology that paid tribute to the work of the British writer of “strange stories,” Robert Aickman. Wehunt’s contribution was an excellent one, about a man who, losing his wife late in life, begins to reconsider his sexuality, thinking of an earlier moment when things were poised to go differently. It seems more of a belated coming out story than a horror story from that description, but let me also mention that the character is gradually transforming, and that the story is driven by gorgeous moodiness and beautifully rendered sentences in which our sense of what’s happening is always partly dislocated by the style — the kind of sentences that you feel like you’re breathing rather than the sort from which you surgically extract meaning. Recognizing this, you begin to understand Wehunt’s particular and peculiar charm.

What matters is that every tool at a writer’s disposal is used to make sure a story works on its own terms

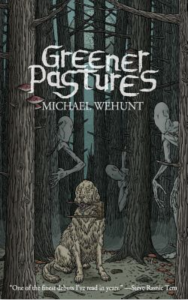

Wehunt is one of those writers (and we’re finding more and more of them in horror these days) who have one foot in literature and one in genre. He doesn’t seem to believe we should have to choose between literature and horror — what matters is that every tool at a writer’s disposal is used to make sure a story works on its own terms. As Simon Strantzas writes in his preface to Wehunt’s debut collection, Greener Pastures, “It’s authors like Wehunt that help show the world that horror is more than the set of tropes that has defined it for too long, and instead is a transformative mode of writing that stretches out and affects all serious forms of literature.”

Wehunt is one of those writers (and we’re finding more and more of them in horror these days) who have one foot in literature and one in genre. He doesn’t seem to believe we should have to choose between literature and horror — what matters is that every tool at a writer’s disposal is used to make sure a story works on its own terms. As Simon Strantzas writes in his preface to Wehunt’s debut collection, Greener Pastures, “It’s authors like Wehunt that help show the world that horror is more than the set of tropes that has defined it for too long, and instead is a transformative mode of writing that stretches out and affects all serious forms of literature.”

“A Thousand Hundred Years” is the story in Greener Pastures that I find most provocative at our current political moment. It is the only recent horror story I know whose main character, Jandro, is an immigrant — an illegal one, but, despite what Trump would have you believe, not in any sense a villain. He’s a man trapped by circumstances, victim to having relaxed into the typically American act of scrolling through his phone while his daughter played on a slide. When that daughter vanishes, he’s sure she couldn’t have had time to disappear. And yet she’s indisputably gone.

Or is she? His neighbor, another immigrant, a Taiwanese one, has something that she claims will help him bring his daughter back. Jandro at first dismisses her, but soon he desperately wants to believe. By the time he realizes what “help” in this case actually means, it may well be too late to stop it. “A Thousand Hundred Years” is a story about the virtual becoming actual in a way that is at once terrifying and — at least for anyone who has suffered serious loss — desirable. The delicacy of that balance, between the terrifying and the appealing, is one of the things that makes Wehunt’s work complexly humane, and makes you continue to think about each story long after you finish it.

Brian Evenson

Author of The Warren

A Thousand Hundred Years

Michael Wehunt

Share article

“A Thousand Hundred Years” by Michael Wehunt

“Tu hija te espera.”

Ms. Onwe’s words echoed his dream, for a moment drew it into the dim hallway with him. Jandro hadn’t noticed the tiny old woman just behind her door, cataracts holding the hall light like wet pearls. He must have misheard her. She would have told him in the past year if she knew any Spanish. Even her half-broken English lapsed at times into Mandarin, where her voice stretched out to poetry.

“What do you mean, my daughter is waiting for me?” he said, hearing the angry waver in his voice. She was going soft, but she wouldn’t say something so cruel to a man whose four-year-old child was missing. He’d lived next door to Ms. Onwe since he and Krista fell apart and he became a weekend dad. They always chatted when he passed her open door, and Virginia had loved her. He had far less to say these days, but she liked to fill the new silences with tokens of sympathy — musty Taiwanese books, chipped tea mugs. Jandro was touched that a hoarder would surrender anything to him.

“They are no dreams you have, Mr. Jandro,” the old woman said, her withered face peering up toward his shoulder. “You need my projector. I hear the movies of your daughter through your wall at night. I hear you cry.”

“Movies?” he said. “Your projector?”

She smiled and her white eyes came closer into the light. “No need to see Chun-chieh and Chih-ming travel on my wall any longer.”

Her dead sons, she meant. Presumed dead, anyway. They had been flying home to Taiwan three years ago. The plane had disappeared halfway across the Pacific, but it had never been found, she’d told him many times. Jandro had learned enough for a good rough sketch of her, listening through the chores he helped with. She’d come to the States in the nineties, her husband had been gone almost as long, and her apartment stank of those two packrat decades.

He found himself almost grateful to put Virginia out of his mind for a moment. Almost. His throat clenched for the handle of rye in his coat, the oblivion and the recurring dream of her that followed each day of aimless searching, peering into the corners of Delmar, turning over the same rocks. After the liquor store he’d spent longer than usual at the playground, his sobbing vigil in the clown’s head, pretending two little hands were on the verge of pushing him down the slide. Krista had refused to update him on the police investigation for more than a week now. Her threats of reporting him to Immigration had gained weight. And while Detective Swinson had yet to say the word suspect to Jandro, the implication still hung over his questions, not quite dissipating.

He followed the old woman inside. “I can take it to a pawn shop, if it’s worth something.” She slipped into the deeper shadows, so he waited at the opening to her living room, the silhouettes of her hoard crowding the small space like a cave of strange teeth. “Or give it to Goodwill.”

Preferably the dump, he thought, along with all these sagging things. The place violated every fire code in the book.

“I want you to see it, not store.” Her voice came from somewhere to the right, followed by a sharp click. An orange-brown light fell from a shaded lamp, landing in a smear that hardly cut into the labyrinth of junk.

“Well, we never really had a camera, and Virginia — ” He stopped. Because he couldn’t get the rest out, and because Ms. Onwe was crouched down behind the lamp. Watching him, one milky eye peering around a square bulk that sat on an end table.

Jandro used his feet as antennae, boot toes brushing cardboard boxes and newspapers and humps concealed in garbage bags. She was no longer behind the projector when he reached her. She stood straight as a rail now, closer than he’d thought, her silver-threaded hair turned brass in the lamplight. Her sons smiled out of the shadows from a large photograph on the wall.

“You take,” she whispered, and laid a pruned finger on his hand. He felt the finger bone roll inside the sleeve of loose skin. Her mouth seemed about to spread into an inexplicable grin. He looked away.

The projector was brushed steel, shaped a bit like a trumpeting elephant with reels attached to the trunk and rear. Jandro touched the cool metal, finding the open design beautiful and too honest.

He lifted it. There was a bad moment when it nearly slipped from his arms, because its size and weight reminded him of Virginia when she was a baby. You’re getting heavy, En, he heard himself say just seven weeks ago, and his little girl hugged his windpipe shut before squirming to be let down, her Spanish lessons trailing back from her in sharp puffs of vapor. He blinked the thought away, leaned the projector back into the seam of his arm and chest.

“Do you know where Virginia is?” he asked Ms. Onwe.

She was so short it felt almost like giving En his stern daddy stare. She looked up at the picture of her sons. Jandro waited but that hot needle of alarm wasn’t in his heart. She often made little sense — today was one more example — but he was sure she would have already shared anything close to helpful.

“No, Mr. Jandro,” she said, still looking at the photograph. Watching it, somehow. “I should not say like that. I know what it is to lose children. And to wait.” She touched his hand again. “Please, take.” That rolling finger bone, its gentle insistence.

He enjoyed the same haze of whiskey, but the dream changed. Redrew its lines. Jandro came out of the woods a few seconds earlier than before, almost soon enough to reach his daughter. His life was full of almost. He watched En float away into the long pale sky, a bright smudge from which her yellow coat tumbled back to the earth like a shed skin. But now, all around him, a dozen or more Virginias lifted off the ground, the sleeves of those fallen coats reaching up for the arms that had filled them.

He thought he could hear their voices, but the cellophane static of radios drowned the words. Behind him, vaguely, was the sense of pursuit. The crackling of transmissions and dead pine needles. The cops were rounding up Mexicans all across this dream Delmar.

A shadow, pooling on the grass beside him. A looming hand. The INS badge gleamed as he was jerked around and a voice growled, “Alejandro de Garza, you are under arrest. Tu mamá te espera.”

His shoulder ached under that hand. But he could only crane his neck, watch his daughter — more than a dozen daughters, now — borne away into the sky. He could only wake. The waking was the awful thing.

Eight times on the slide. Eight or nine. The real question was how many seconds he’d spent checking his phone that morning. He had no memory of what the email or Facebook post had been. All it took were those few moments with his eyes somewhere else. But he kept trying to count her loops anyway, like picking a lock, eight or nine times on the slide.

They’d had the playground to themselves so early and cold on a Saturday morning. En had insisted. She ran for the swings first, the stubborn dark tangles of her hair bouncing, and Jandro sent her just high enough for a four-year-old to pretend the sky was too close as it fell toward her. “Cielo, tierra, cielo, tierra,” she chanted. She wasn’t learning Spanish anymore at home, so he tried to coax it into her the two days a week he had her.

She always saved the slide for last but could never wait long. The play structure was a giant clown’s head, red hat and faded white face, and she loved it as much as it creeped Jandro out. There was a rhythm to her then that he’d memorized across a long string of weekends. The thuds of her sneakers up the ladder, her fisherman-yellow coat crinkling as she shifted into just the right spot, the lift of her voice into a half-squeal down the other side, and the slow whisk of plastic against the butt of her favorite pink corduroys. Repeat. Repeat. Watch me, Papá. Watch me, Daddy. And he had, most times he’d been happy to.

Eight slides. Or nine. She’d taken countless trips down it in the year after she and Krista had left him, it was their Daddy-En Saturday morning ritual along with their secret doughnut breakfast, but you couldn’t always hold them in your eyes. There were cracks in time when you saw a pretty young mom with a stroller. When you looked up at a gliding hawk, distant as a mote in a cloud’s eye, or rooted for a wet wipe thinking her runny nose might need it. All those times you sat there on a bench thumbing your phone screen. Because you always knew the sound of your little girl’s voice and the loop she made, up, settle, down, run back around.

And when the rhythm of her had cut off that morning, suddenly not there, Jandro looked up and saw right away that the playhouse was empty. The purple slide that came out of it like a bruised tongue, the ladder up into the clown’s head, empty.

Behind him had been the drowsy street. Ahead, the wide, short field beyond the playground with only faded grass waiting for spring. The brief postscript of woods lay beyond it, but her little legs could never have reached them in the moment he’d looked at his phone. En loved those trees, liked to make Daddy hold his breath when they walked through them from the apartment building, because the air was poison and would make him fall asleep for a thousand hundred years.

He’d stood up into that breathless quiet and called her name, Virginia, Virginia. Her second word as a baby had been to pluck En out of the center of that mouthful, and Jandro only called her Virginia in scolds, or in the cold moment every daddy hoped would never, ever come.

She was gone. An image, cobbled together from all the fears that live in the backs of parents’ minds — his daughter with a greasy hand clamped over her mouth, dragged into the trees, into the alley across Milton Ave., into dark places full of implacable horrors. He played his mental En-tape back. The last thing had been the sound of her shoes climbing back up the ladder. All the looks he got later, all the detectives’ questions, the ringing in his eardrums after Krista’s screams, wouldn’t change that. There had been no child predator, no dirty fingers groping her, stealing her away. She hadn’t gone down the slide that last time. Up the ladder, and there the loop of her hung broken in his mind, calling out its echo.

He opened his eyes, still drunk, and saw something in the room with him, a low black lump in the center of the studio apartment near the kitchen island. He and the shape waited in the dark together, Jandro swallowing his daughter’s name, swallowing it again, finally whispering, “Ms. Onwe?”

It did not answer. Jandro thought he saw other shapes, sliding out of the bathroom doorway, crawling into the far corner of the ceiling above the refrigerator. There came a dry snapping sound, a metallic click, repeated several times. Like a light switch, a blown bulb. Quiet spread. He drifted off until it was morning, flat winter white and bruising cold.

He woke and scanned the apartment for detritus from his visitor. For a long moment he stood in the middle of the single room, shivering, trying to decide if it had been a new dream.

The door was locked, but the window was open several inches. Outside it was wet enough for the snow to clump together before it landed twenty feet below. He checked today’s fresh line of footprints leading away from the apartment building to the trees, the park beyond them. He’d learned not to trust those prints, though they were small and shallow enough. They could belong to anyone’s kid — the building had three or four around toddler age that he knew of. And the tracks filled so fast in all the snow. His heart ached to think of spring, when this strange trail would be gone, too.

He closed the window and leaned his forehead against the pane, relishing the cold, willing it to tighten the blood vessels in his brain. A quick breakfast shot of whiskey handled most of the headache, but he could never shake it all off.

He had to find work. Mr. Callum at Daye Construction had hated to let him go. He’d had five good years with Daye, solid work and respectable pay, and as an illegal you didn’t just let something like that slip away. But he’d been a drunken wreck after that morning at the playground. A month later he’d been even worse, without even the pretense of showing up at the job sites.

Of course En was probably — he came closer to thinking the word than usual, but still couldn’t allow it. But he understood the near inevitability. And his mother’s lymphoma wasn’t going to cure itself, her slow death back in Puebla. He hadn’t had the heart to call her once since Virginia had gone missing. She had never even met her granddaughter, and he couldn’t bear to tell her she never would. So here he was, losing his mamá, too, in all of this. He was missing the end of her life, two and a half thousand miles away in Delaware.

But she needed an influx of cash that he was running out of. He had to work. This crusade was grinding to a bitter end.

The projector stood on the granite island that, flanked by two barstools, served as his counter space and dining table. It was a simple model: a few knobs and toggle switches, a lens with a focus dial around it. An odd nub protruded from the back of the machine, covered with foil mesh. MICR had been written below it with a felt pen. He stretched the cord over to the counter and plugged it in beside the toaster.

A powerful urge to call Krista came to him. To feel the sharpened ice in her voice, to hear the words between her words, the true sentiments that hid in her long pauses. This was his fault. He had lost their daughter. She was glad she’d never married him, because now he could get shipped back to Mexico once she told the police he’d never gotten his green card. He knew how to wear this ballast of guilt. Part of him yearned for it.

Instead he flipped the toggle to ON and an electric hum rose. The reels clicked to attention, the rear one full and the front one just a bare spindle. He had no clue what he was doing, but the film seemed to be threaded already, so he flipped another lever, labeled OPER. The reels spun, the tape traveled from one wheel to the next, and a blunted square of light appeared on the wall above his bed.

Blank white played out for a while, then Jandro shut the projector off. It was time to search for En. Time to repaper the neighborhood with flyers, to linger outside the police station, dredging up the courage to go inside and ask for Detective Swinson, demand some information, anything but nothing. Dreading that when he finally did, the INS would be brought up. The questions, the searching glances. Time to end up sitting inside the clown’s bright head, his nose raw from the constant swipe of his army-surplus coat sleeve, waiting for two little hands to push on his shoulders, a voice to say through the giggles, “My turn, slide hog!”

Or he could empty the bottle of whiskey into the toilet, flush it into Delmar’s bowels, and find some work. The thought of spending time looking for anything other than En tore at his gut. He went back to the window, stared down at those footprints leading away toward the strip of woods. “Mija,” he whispered. He always counted on that little word to hold everything.

Jandro still held his breath every time he passed through the woods. It was his benediction for his daughter, however much he would have liked to sleep for a thousand hundred years and have En wake him with a kiss. It took barely twenty seconds to walk through the trees, motley clusters of Scotch pines, skinny birches, a few stout oaks.

When he stepped out of their shadows, letting his breath plume out above the quilt of snow leading to the playground, he stopped. Something felt different. The town was holding its breath, too. He watched the clown’s wide dinner-plate eyes, the too-small pupils. The only obvious thing was that the clouds seemed to be drifting around the little park, framing an irregular oval of sky. And the feeling, sharp and ineluctable, that he shouldn’t go any farther today.

Turning around felt like a betrayal, though. Krista had said endlessly that En had probably snuck down the slide and started a game of hide and seek, waiting for Daddy to catch on. And someone else had found her, instead. Jandro just couldn’t admit that those few seconds on his phone had been minutes. No one got it, how he knew En’s rhythm, it was like the pulse in his blood. He still felt it, even now, pulling at him.

But he filled his lungs with the cold air, closed his mouth tight, and retreated through the trees.

Mr. Callum was kind enough to refer him to a job, so come morning he’d have a week’s work finishing up two houses in a development out on Springer Road. Grunt work, sanding cabinets and tiling bathroom floors. Jandro capped the bitter success with a hand’s worth of rye in his old Hamburglar glass, the one that always made En giggle.

He found himself orbiting the kitchen island and the projector marooned on it. Studying the knobs and switches, his eyes came back over and over to the microphone. The blank reel had no sound, of course, so he had no way of knowing if the microphone was only an odd extra speaker. But he was haunted by the insistence in Ms. Onwe’s voice. The visitor in the night, or his dream of it, snapping the toggle switch up and down. Twice he nearly stepped into the hallway to knock on her door, but he was drunk and it was late.

Around midnight he hid the bottle of whiskey in the pantry. He turned the projector on, leaned close to the microphone, and whispered, “Where’s my En? Tell me where she is.”

He wandered over to the bed and fell across it. “Where’s my little girl?” he asked again. Passing into something like sleep, he remembered he had more than a new set of kid-sized footprints to set the alarm clock for. He slept and if his dream came to him, it was too distant for him to recall, just a speck against the sky, a hawk or a precious thing called away from him in secret.

Jandro was grateful for the hair of the dog the next morning. After nearly two months out of work, his fingers cramped and began to blister. His knees flared with pain. He tried to pray since he was already kneeling, but it seemed God’s ears had crusted over some time ago. The foreman, some guy named Franklin he’d never worked with, called him Paco all day, and near dark Jandro dragged his weighted bones onto the bus. It was snowing again. When he focused on the flakes swirling past the window it was a kind of hypnosis.

The whiskey still stood in the pantry’s shadows, Jandro at his place by the window, pushing the bottle’s pull. There hadn’t been any footprints this morning, but it had been five a.m. when he left, and the new snow would have filled them in.

The dark tree line drew a seam across the sky, a pink echo of sun fading through empty branches. He watched and ached. He thought of the life that had been taken away from his daughter, the great puzzle of traits and decisions she would never get to be and the quirks she would never grow into. She’d hated milk — what kid ever said that? And where might that dislike have led her? Jandro remembered stealing a candy bar from Cordava’s Mercado as a teenager, how Cordava himself had chased him across the street and knocked him down. He’d lost two teeth against the wall of the auto garage, which had made him too self-conscious to really smile until he’d gotten a bridge seven years later. He’d been sullen, bashful, a virgin until he was twenty-two. How much of his life, his path, his character came from that stolen Mars bar? What mistakes and the arcs of those mistakes would never be allowed to shape En?

“Buy a cheap car,” he told the window and its scrim of frost. “Drive south along the Gulf, until Texas ends. Breathe the last of this air that doesn’t want you. Head home to Mamá and be there when she goes.”

He said these words, or something like them, every night. To taste the thought. Watching the sun bleed out, watching the purpling of the snow out on the lawn. Chasing these ghosts. “Lo siento, mija,” he whispered. He pressed the bones around his eyes, then turned and looked at the projector. It took a moment to notice the difference. The front reel was full and the back was empty. It had been the other way around the day before, he was sure of it. A small thrill found him. He looked around the apartment, heard water coursing through the veins of someone’s walls, smelled the unwashed, given-up stench that never left the air around him. He turned the projector on.

The white absence on the wall lasted only a few seconds before a deep red replaced it. Jandro switched it off in a panic, then swiped the comforter from his bed and pulled the sheet off. It was white. It would do. He rooted through his tool belt for nails and hammered them through the sheet into the drywall above the bed.

He flipped the lights off and the toggle switch back up. That deep red threw itself across the sheet, sharper now, shifting like something seen through eyelids that had just opened. A point of dark blue bled into the center, but Jandro didn’t know if it was a flaw or part of the image.

Then movement, and that navy smudge came closer until it had the circumference of a poker chip. Another color intruded along its edge. He thought of a blue moon, in the first moments of eclipse by a hint of green beyond.

He found the focus dial around the lens and twisted it. The image only smeared further, so he turned it back. What he was looking at changed. The red wall rose up and he saw a strip of violet-blue sky, a ragged suggestion of treetops in the distance. His heart caught and he couldn’t breathe. The view tipped forward to show a patch of sand, then two small legs in pink corduroy, two little white sneakers, and the world streamed by. Jandro felt that old rollercoaster lurch in his gut. En, on the slide. Where’s my little girl? he’d said into the possible microphone. Her pink corduroys, her Saturday pants. On the slide.

Jandro wasn’t aware of opening the door. He didn’t see the hallway. The world came back to him in the rush of cold air in his ears, the crunching of snow under his work boots. The world ran with him across Adelin Street toward the trees. He gulped a huge breath at the last second before he crashed into them, dodging trunks, eyes on the field beyond. The snow cast its own ghost light at him, and somewhere off to the left static muttered. He didn’t stop, hardly even thought the word radio.

The clown’s head sat waiting for him like a cabin in a vast wilderness, as it always did, something he should never have abandoned and was lucky to return to alive. The west end of Delmar seemed distant around it, muted against the bright colors, the dejected silhouettes of the three swings, each with a rictus of snow upon its seat. It had been a sad little park, even before.

He reached the swollen purple tongue of the clown and scrabbled up the slide into the arch of its toothless mouth. It was empty. But for the deep pocket of shadow he crouched in, it was as empty as it had been the day En never came out of it.

“Virginia!” The only answer came as a soft crackle drifting from left to right to somewhere behind him. Jandro slumped down into the cold dark until he remembered the circle of sky he’d seen projected on his wall. At the apex of the clown’s head, where the pyramidal angles of its red hat met, was a small hole. It framed the sky beyond in a full blue moon. He traced it with a finger, then raised himself to peer through. If there were stars, they hid behind two curtains of clouds, which bowed around the playground as they had done the previous morning.

The sky he’d seen above his bed had been a blue darkened perhaps half an hour past dusk. And that faint green, whatever it was, had partly eclipsed the hole in the plastic. There was no green now. It was past ten p.m., and Jandro wondered if he was too late, if going back to work had thrown him off course.

He’d allowed himself to think before that this playground might be a thin place between worlds, or planes. He could never share such an opaque, abstract idea with Krista, so invariably he found himself here, silent and trying to feel Virginia’s hands on his shoulders.

He waited a long time because her little shove felt more possible than it ever had. She hadn’t gone down the slide. Finally Jandro did — he squeezed his legs through the clown’s mouth and slid down the tongue, feeling snow soak the seat of his pants.

Ms. Onwe didn’t answer his knocks, even when they turned into pounding. Her door was locked. A voice from 2B across the hall yelled something, and Jandro gave up and went inside his apartment, where he begged the projector. He gripped its brushed-steel casing and asked the nub of microphone, “Where is she?” and a dozen variations on that theme.

He thought of calling Krista to tell her that Virginia might be trying to find him, but couldn’t shape the words in a rational way. Instead he set the projector up again to finish watching, to search for clues, but the reel was now empty. The ache of his body and his strange thoughts wore him down soon after and he slept, haunted intermittently by Ens floating away from him. He counted them, reaching seventeen in the last of the dreams, until a shadow unwound onto the grass beside him, and he woke to the flapping of the projector’s reel.

Someone had left the window open again. He stared through it, bleary-eyed, the tautness of the decision he had to make thrumming like a guitar string. If he ditched work he didn’t know if Mr. Callum would give him another chance. He’d be consigned to the Lowe’s parking lot, puffing out the chest of his thickest coat to appear stronger, more durable. There weren’t many illegals in Delmar, but they still worked cheap, and he had ten years on most of them. It had been a long time since he’d had to hope his way into the bed of a pickup.

He had to leave soon to catch a bus. But the projector had filled again. He didn’t know how, but his questions had been answered a second time. He imagined working all day, lost in the whine of the power sander, with the knowledge that En might be close, that there could be a key to some unknowable door —

He flipped the switch. The silent red ceiling flickered to life on the wall, and Jandro stood frozen as it played out. The sky through the hole in the clown’s head was the same deep navy, but its shape was a crescent now. That out-of-focus green occluded more of the sky through the hole, pushing the blue toward the edge. The image of a moon was the only one that felt right in his mind, these phases of Virginia. As before, the scene felt nothing like a film, nothing captured through a mechanical lens. It lacked a sense of defined frame, with rounded edges that felt closer to true vision.

The scene shifted, as it had yesterday, but the legs that unfolded themselves onto the slide now seemed longer and fuller through some trick of faded light, the pink corduroy stopping at the shins and tight against her legs. The purple slide a quick blur, the pale sand.

The woods shook, drawing closer. Virginia was running toward the trees. A breathless, silent trembling of the world. His body tensed with the realization that she was heading straight for him, this apartment, her weekend home, but when the trees flowed over and around the periphery, she stopped. Shapes moved, perhaps closed onto her. He couldn’t pick anything out of the murk. He climbed onto the bed and tried to keep his shadow out of the projector’s beam, hunched on the stripped mattress and peering up at the image like a cowed animal, but it faded white and the reel ran out behind him.

“Sand,” he said. His mind had gone back to the slide. “Sand. The snow’s melted. It’s not time yet.” He scrambled off the bed and over to the window, as though to verify that spring hadn’t miraculously fallen onto the bottom corner of Delaware overnight. Through the trees across the street the sun rose with perhaps a new intensity. There were no footprints in the snow.

But the sand. He needed to wait until the snow melted and there was only sand on the playground, and the flaring hope it brought him. He went to the projector and spoke, slowly, enunciating into the microphone: “Please tell me how to get Virginia back. Please tell me when, and how. Please tell me what I need to know. Que dios te bendiga.” He kissed the mesh nub and grabbed his coat.

Something thumped inside Ms. Onwe’s apartment as he passed in the hall. He stopped and pressed his ear to the door. A sliding, dragging sound. It could have been the old woman struggling with any of the hundreds of things she had in there.

He was already going to be late to the job site, but he knocked anyway. “Ms. Onwe?” He knocked again. “It’s Jandro. I need to talk to you about your projector. Please.”

There was no answer. The dragging sound had stopped. He tried the doorknob and it turned in his hand. A deep stink — gone food and mildewed laundry, worse than usual — clouded into his face as the door opened on a wedge of dark.

“Ms. Onwe?” He stepped in, pulling the collar of his army coat around his mouth. There were no lights on, and from the door he could see none of the dawn that was building outside. The brief throat of her hallway opened ahead into the close musty living room. Nothing for it except forward.

The stench deepened, became older and more complex. Heavy curtains or blankets over the single window shut the room into a tomblike black, within which his boots encountered resistance in every direction. Jandro tried to recall where he’d stepped through the hoarded junk the other day, to the lamp and projector.

“Are you home?” He listened, caught a chewing or smacking sound in front of him, something damp and suckling. Sliding to the right, he found the path, remembered the bend only when his shins knocked over a pile of magazines or newspapers. The wet sound continued and Jandro moved on. Soon his hip banged a table, and the lamp wobbled, telling him where it was. He reached down and clicked it on.

Filmy orange light puddled below, and cast in its weak glare a knot of black and white shapes moved on the floor, several feet from where he stood. He couldn’t decide what he was looking at until the shapes resolved into figures, kneeling or on hands and knees, bent over something in a loose circle. Tilting the lampshade up, he threw a heavier smear of light on them. They were pressing their faces against a focal point beneath them, kissing it, their mouths making soft moans. In the stronger illumination some of the figures pushed themselves up and turned to regard him. As many as fifteen Asian males, short, and of greatly varying ages. He saw two hardly out of their teens and three stooped, withered old men. The rest were in between. They all carried a strong familial resemblance, as though several generations had gathered here for some rite, dressed in white button-up shirts and black pants with bare feet. The last few finally, grudgingly, lifted their faces to Jandro, as well. The dozens of eyes watched him. He thought of zombies, ghouls, something he could pull from a movie and plug into this, but their mouths were only drool-slicked, with no trace of blood.

And at last he saw the subject of their ardor. Ms. Onwe lay on the floor in a long powder-blue tunic. Her face shone with wetness even in the low light, and Jandro thought she was dead until her pearled eyes opened and rolled toward him. “My boys,” she said. “Chun-chieh and Chih-ming, they always find me. Always love me.”

The figures slowly returned to the floor and to moving their mouths over the old woman. They kissed her, extended their tongues to press against her body. “She close, Mr. Jandro,” Ms. Onwe said from under them, “your daughter. Close when she left.”

Jandro fled, triggering an avalanche of junk in his wake. Who in God’s name were those men? What had the projector shown the old woman, and for how long? By the dirty lamplight he found the hallway and stumbled out of the apartment. He was in the street, turning toward the bus stop, before he felt the difference in the air. A warmth. The sun broke through En’s poisoned trees in postcard rays, and he tipped his head back to see snowmelt dripping from the building’s eaves and trickling from the gutters. If it was this warm at six a.m. —

The old weight rolled over him: He forced himself again to think of his mother, go to work. All the hours before dusk had to be filled, anyway, and he could send her money in a few days. Talk to her neighbor, Lupe, find out if chemo was still an option. He felt shame, that he didn’t know the answer already.

The bus drifted through slush and Jandro’s mind went with it. At the unfinished house he let muscle memory guide his work, held in a vacuum of soft, pressing expectation. Every five minutes he checked a window to make sure the sun still bloomed down. It was late March. A sudden spring would not quite be a miracle, but it would be close enough for Jandro. He tried to pray, and imagined he could feel his words at last being listened to.

The snow had shrunk to gray tumors along banks and curbs by the time the crew knocked off. The sun beat like a revived heart, mid-seventies even an hour from dusk. Coming home on the bus was like waking into his dream, and it was all he could do to avoid the park. He went up to his apartment instead, hurrying past Ms. Onwe’s door.

The projector had a full reel but only showed him six minutes of the ceiling of the clown’s head — the square of red and the moon full. Not with blue or the blurred green of before — a mess of vague color, whitish, black, brown moved inside the circle. He went to the window. The sky lowered, draining from a richer orange to peach to yellow, then began to fill with a quick dark blue that caught him by surprise.

He ran to the stairs, down and around and out of the building, nearly colliding with Krista as he emerged onto the sidewalk. Her makeup was a ruin beneath her eyes. He had no idea she’d started wearing makeup.

“Just tell me where she is,” she said, her voice thin and rising from the first word. “Tell me. I can tell Immigration it was a false alarm if you just say it.”

“Immigration?” A coil of anger tightened in his chest. “You reported me? Don’t talk like this, Krista. You know I don’t know.”

“You did something. Or you’re hiding something. I’ve thought and thought and it’s the only thing that makes sense. You — ”

She shrank back from him. Jandro had never come anywhere close to striking her, through all the arguments and recent accusations. But his hand rolled into a block, and his arm tensed. He breathed. “I would never.” He breathed. “Hurt our daughter.” He pushed past her.

“I told them to come now,” she called after him. “Where is she?” The rest of her words bled away as he crossed the street toward the woods. He filled his lungs with blessed, new spring air and pushed through.

The playground lay in an envelope of dying light when he came out of the woods, the clown’s head squatting in the center. There were no clouds, so he could not discern the aperture in the sky, if it was even still there. He jogged across the patchy field, the grass bleached a sickly beige after months packed beneath the snow. But it was sand ringing the playground when he reached it, damp, with only a rind of slush along the edges.

He climbed up the slide and waited. He imagined being arrested, watching the judge hold up his deportation papers, the stern voice an atonal blur against the beating in his head. He thought of finding Virginia and being forced to leave her in the next moment. The sun seemed to sink in a final ellipse around the park, turning the west of Delmar briefly golden.

“But what did the moon mean?” he asked the night as it folded itself around him. The projector had emphasized those moons, and again he stretched up and peered through the hole in the ceiling. Nothing but the empty sky. It hit him then — the view shown by the projector had been from inside this play structure. And something had partly covered the hole. Something green. Something outside. He held up the sleeve of his drab olive coat.

He leaned out of the clown’s mouth and turned himself. It was a moment’s work to climb to the top of the red hat and cling there, surveying his barren little kingdom but not really seeing it. He lowered his face to the hole, slowly, thinking of the phases of the moon as his eye eclipsed it, and peeked through. And there she was. En. Her yellow coat and pink Saturday pants, her tangled dark hair.

When she saw him looking she giggled, scooted away, and shot down the slide. He heard the little squeal, the one that had been caught in the ether for nearly two months, finally release itself into the air. “Virginia!” he called, but she was off and running toward the field and the trees.

Jandro shifted to swing himself down to the sand. Something moved through the hole, inside the structure. He dipped his head again and watched another En laugh then move forward toward the clown’s mouth. She was bigger now, the size of an eight-year-old. The pink corduroys were more like capri pants, snug around her shins. Halfway across the field the first En ran with her arms up in airplane wings, teetering side to side to simulate flight.

“En!” But this second girl had already gone down the slide and was following the first. Jandro let go and braced his legs for the impact. The jolt spiked through his left ankle, which turned against the wet sand.

He set off at a limping run but then stopped. Other figures converged on this side of the playground. All female, all of them with an inexplicable yellow coat and pink pants. One little Virginia ran up to him and said, “Daddy!” as she hugged his leg. A sharp sob escaped Jandro, but she was gone before he could wrap his arms around her. A woman passed in front of him, beautiful, black-haired, with the sharp angles of Krista’s face hiding under Jandro’s complexion. She peered at him, narrowing her eyes. “Dad?” she said, confused, then walked toward the woods.

Jandro swiveled left, then right, taking in these fifteen, twenty daughters. A hunched old woman came up to him, with long silver-streaked hair, webs of fine wrinkles turning her face almost to paper. He saw so much of his mother in that face. For a moment she seemed on the verge of reaching out, in tenderness or for support. But she looked away shyly, then followed the others, passing another woman whose hands were laced over a belly swollen with pregnancy. His grandchild.

He thought, with a sick lurch, of the figures in Ms. Onwe’s apartment. It came to him now that he had recognized those men, had seen variations of them gazing out of a dozen picture frames hanging above Ms. Onwe’s hoard. Her lost sons. How far they must have come for their mother, three years across an ocean and a continent.

But these Ens did not seem profane in any way, and he understood that not only had he found En, he had found perhaps every En. All his possible daughters on all their possible paths, their threads of decisions, beliefs, and joys. All the ways her dots could have connected from the nexus of that morning when he lost her. It wasn’t a matter of which was the real En. They all were real enough.

For a moment he could only stand and watch his girls, thankful that not one was being pulled into the sky. Off in the distance, on Milton Avenue near the municipal building, a police car’s flashers burst into life, stuttering an unnatural blue into the night. Two figures emerged from the car and came toward the playground. The park was closed, Jandro told himself. Nothing to worry about. They would tell him he wasn’t supposed to be here. They were regular cops. Krista hadn’t really made that call.

“La gracia de dios, Mamá,” he murmured, “si pudiera estar aquí,” and followed the Virginias, the pain in his ankle forgotten. He saw another, in her late teens, whose right arm was missing at the elbow. She walked behind the others, staring down at the half-dead grass, and he quickened his pace so that he could comfort her, find out what had hurt his mija.

But she passed into the woods alongside the elderly Virginia. They were gone. A crackling drift of sound, either from the approaching figures behind him or as the last few rattling leaves in the trees. He plunged after his daughters, shouting their name. Black shapes stirred and came forward. The dark had grown past full, and within it arms reached out and touched him. Reunion found him. He only hoped that each one of his Ens would have the greatest blessings of life, that their sorrows would be small and their hearts full.

“Daddy,” one of them whispered, then another, and another. Something was wrong with his head, a lightness and a terrible weight. He had forgotten to hold his breath. Yet all these soft arms, they stretched and embraced him there in the trees, kept him from falling, and Jandro breathed in the first moment of an eon.