Craft

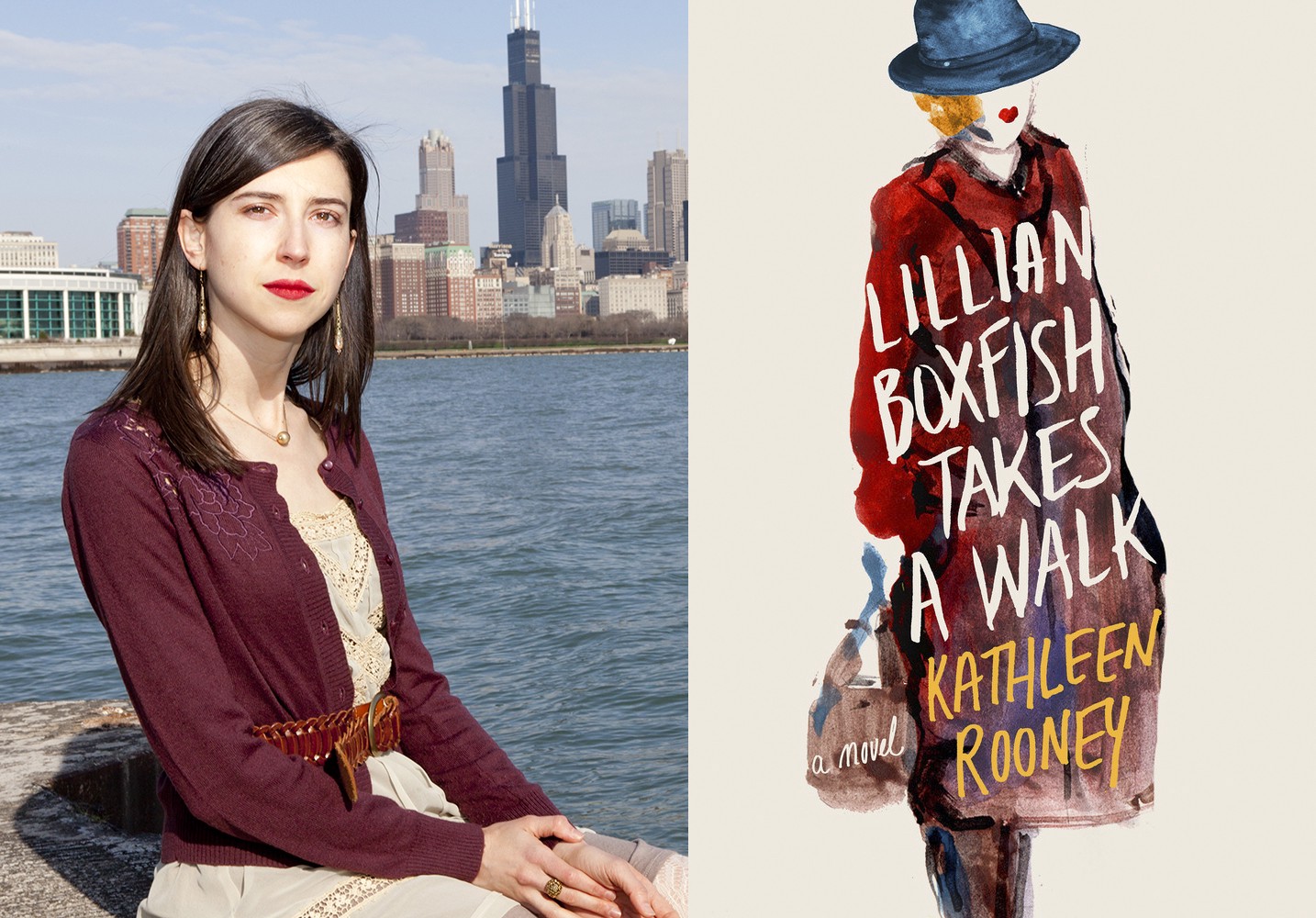

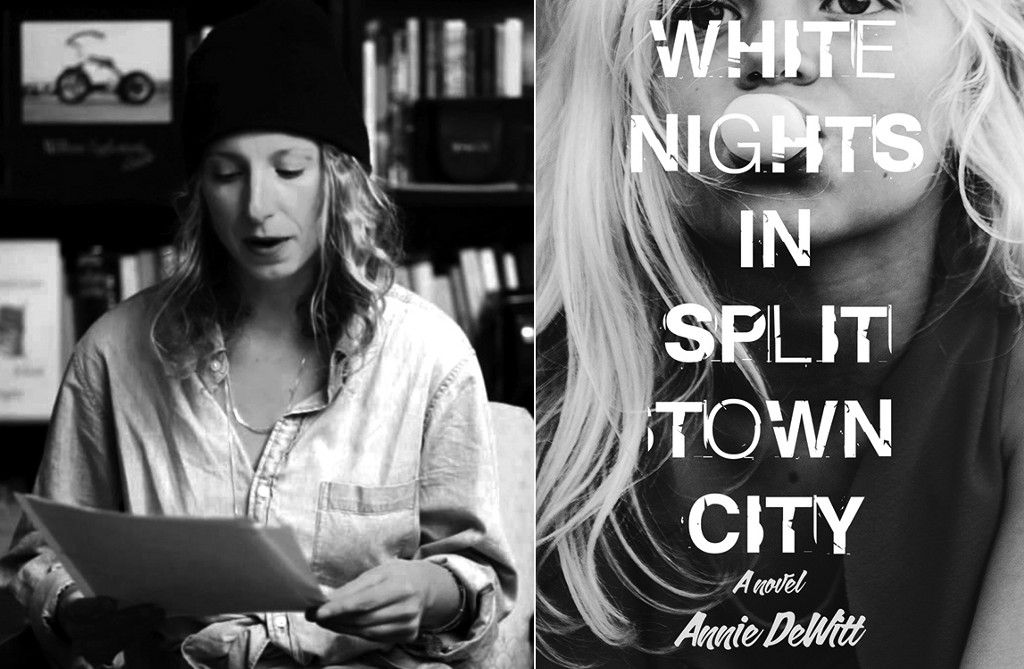

Annie DeWitt Investigates the Countryside

The Author of White Nights in Split Town City talks with Kristopher Jansma about unpaved roads and rough survival

If you’ve ever read Annie DeWitt’s stories in Granta, Tin House, The Believer, or BOMB, then you already know that she has an incredible sensitivity to both language and character, strengths that she brings to great use in her debut novel, White Nights in Split Town City (August 9th, Tyrant Books). A co-founder of Gigantic and an adjunct professor at Columbia University and elsewhere, Annie’s thoughtful novel has much to teach us about the summer of 1990 and the life of a girl named Jean who lives in a rural and vividly rendered small American town on Fay Mountain. When her mother leaves their family for the ever-encroaching larger world, Jean finds the only home she’s ever known rapidly unraveling. Together with an abandoned boy named Fender Steelhead, she begins a memorable investigation into her town, her neighbors, and of course, herself. It’s a stunning achievement that feels like a new classic in the coming of age genre, pushing the usual boundaries with every exact and envisaging sentence.

DeWitt and I talked about it over email last month.

Kristopher Jansma: Annie! There are so many remarkable things about this novel that I had trouble deciding where to begin, but maybe it would be best to set the stage first. You present readers with a very rich landscape in and around The Bottom Feeder, which seems so untamed and wonderful and as seen through Jean’s eyes. Things there have these benevolent, mythic names: Old Eagle Back, the table, and Baby, the piano, and The Sheik… Maybe a good place to start would be to ask how this place came alive to you as you were writing?

Annie De Witt: To me, one’s sense of place is a defining character. It centers us — our view, our circumstance, our weather, our dialect, our language, our religion (or not) and (to some degree) our moral compass. I’ve always been entranced by writers who explore the majesty of that relationship. I’m thinking of writers like Annie Proulx, Flannery O’Connor, and Marilynne Robinson. And, in nonfiction, Annie Dillard and James Baldwin.

I belong to the countryside and it belongs to me.

I am an old soul. I belong to the countryside and it belongs to me. I grew up hearing the voices of so many of these characters on the rural unpaved road where I spent my childhood. To me there was nothing exceptional about this — other than the way that time seemed to slow in the summer. As a child, summer seemed to me to be 75% of the year — it expanded on one long golden reel and was bookended by the school-ish seasons of fall and winter. There was an expansiveness to this place which spoke to me then and continues to now.

I recently moved back to a rural enclave in Delaware County, New York. This place was once the milk seat of the U.S. and continues to try to hang on in that fashion. The landscape is dotted with ramshackle barns. My closest neighbors are cows. This winter we had five raccoons living on our ceiling. I wake up and check the trail cam to see if beavers or foxes are building a nest under the porch. Often, there are both. Once after a run, I came home and saw a black bear with her two cubs in the pine glen next to the house. This place is home to me. But, I had been away from it for so long. It feels good to return. There is literally the same “Dead End Road” sign on my corner now as there was when I was a seven. I try not to take this as a metaphor!

Q: You capture that kind of land-out-of-time thing really well, as well as the tentative balance the characters within it have with that natural world. But there’s this contrasting sense of encroachment: AIDS, TV, computers, cancer, and the end of the Cold War. They are all the beginning of a new kind of fear. And there’s Fender Steelhead and his abandoned brothers, with Fender tied to the roof of the truck as it careens downhill. Jean and her mother just watch. Such a great scene. Can you talk a little about those contrasts? Is it modernity or adulthood (or both) that’s encroaching on Jean, on all of them?

A: The beginning of a new kind of fear. That’s exactly it. I just returned to the Catskills from the city late last night. It has been such an awful summer. The mass shooting in Florida, the assassination of Alton Sterling in broad day light, the shooting of five police officers, and now France. So sad and violent and bloody.

Mostly it just feels like an odd time to be trying to promote a book, what with all that’s going on in the world. I was driving home from an interview near Union Square this afternoon and getting push notification from The New York Times about the attacks in Nice. New York City had seemed so heavily armed and militaristic to me. Police in riot gear with their white NYC motorized mini-vehicles lined the entrance to Chelsea Market and Union Square Park. Such a sad and violent summer. It reminded me of Joan Didion’s descriptions and depictions of LA in The White Album after the shooting at Alabama State. I wonder about the world and our collective future. So much unrest.

All of this made me reflect on what transpires at the beginning of White Nights. How blind we were as a nation to the fallout of the Gulf War and America’s involvement in the Middle East. This is what I tried my best to paint in that beginning chapter — a kind of backdrop of a world in flux. The Berlin Wall falling, the USSR collapsing, the fear of AIDS etc. To me, so much of this fear is what the news (and sadly politicians) capitalize on. And too it is what the mother in this book becomes obsessed with — the desire to “find some national story and feel moved by it.”

Modernity is encroaching on all the residents of Fay Mountain — this thing which has a false aura of truth and transcendence (i.e. represented metaphorically by the mother’s glass windows which let “some of the world into the house.”) And yet so much of that modernity goes on to be redacted and sensationalized — much like we find out about at the end of the book with the stories about Cash and the Doctor.

Q: That’s really interesting! Hopefully we’ll find the same to be true, eventually, about the modern fears we face now? It is surreal, to be sure, to be going about the business of promoting a book when it feels like the world is coming apart at the seams. The more I talk to others though, the more I find them, and myself, talking about books and music — maybe it’s escapist on some level, but maybe it is also what we turn to in times of fear.

All of that to say that I think a book like White Nights does such a powerful job of evoking that “new kind of fear,” that it can resonate with this present moment, and future ones, and maybe even bring readers some hope that we’ll come through it with a new kind of strength.

One of the things I loved most about Jean, the protagonist here, is her resilience and strength. Chapter two, I think it is, opens with this lovely image of an old apple tree, that despite its neglect by its human owners, inexplicably keeps right on producing apples — albeit bitter ones. Her mother points it out as proof of “the wayside of things,” which seems like a kind of a strength that comes from the land and from nature, and maybe even filling in where a void is left by the neglect of the people who are meant to care for something? It’s a powerful image and it rings so clearly later in the novel when Jean’s mother leaves them. And of course in Fender and the Steelhead brothers. Is there some kind of strength that rises up from their abandonment?

A: Absolutely! I love what you say about the image of the apple trees. In the book they are referred to as the two trees of knowledge. I think that as one of the metaphors I appropriated early on in life — that the need to keep going is above all the need to survive. I always admired and respected that about nature. That it survives despite all odds. You see massive trees growing sideways out of sheer rocks faces; their roots entirely exposed. And yet they are still reaching upward.

There’s that section where Jean describes her mother thusly: she fostered what the children of all first generation immigrants feared, an innate feeling that the day to day was long and hard and struggling but as the city teamed around you progress was being made. The struggle was the pride of it. It was only in the face of adversity that Mother was ever truly free. Under Mother’s feet, there was the kind of ice made for skating. It was thin. But she was light.

Yet, in the end, as often happens in families, the cycle repeats. The Mother ends up being the one who abandons her children and, in a way, forces them to confront these words head on in her absence. To the Mother the “wayside” is a place of little opportunity or importance. To Jean, it is the bedrock of her imagination and a source of great strength.

Q: That works powerfully all the way through to the end of the novel: the cycle repeats. I’m curious how much of this, thematically, character-wise, and so on, did you have worked out when you started writing this book, and how much evolved as you went along? Can you talk a little bit about how the creative process works for you?

A: Thank you, Kris. Your questions have been so fantastically evocative. The process of excavating this book was long and drawn out. I was working several jobs along the way — often two or more at the same time. What I can say is that I’ve learned tremendously from it. I’ve learned to trust my gut. The first draft of this was written in a seven-and-a-half-foot wide studio. With another human body living it — namely my partner, the photographer Jerome Jakubiec. We were both starting out and the struggle to eat, live, pay rent, survive in the city, was real. That studio and the Hungarian Pastry Shop on the UWS (god bless them and their pastries) were the physical spaces where this book first existed. I was working with a different agent then and our communication was tenuous. I ended up spending a year rewriting it entirely in the third person and wasting a lot of time. Though some of this interiority on the part of the other characters, beyond Jean, was helpful. I got to see inside Otto. To see inside the Mother. I don’t know that much of that still exists in the book — but it was therapeutic on some level. A flushing out. Then one night, three years later, I was walking around Brooklyn and a friend said to me, “I see you singing. I see you standing at a reading and singing your words. In your own voice and people are clapping.” It was then that I knew I needed to return to the original first person draft. It took several years and a lot of changes, but eventually I excavated that original raft and expanded on it. Did research. Edited greatly. Went through a serious depression and crisis of self-doubt. And eventually I emerged with a book.

I’ve learned to trust my gut.

My creative process with this book was so intimate, as it was the first. I worked laboriously on a sentence level even in the first draft — reading everything aloud, making cuts, saving so many different versions of paragraphs. I wouldn’t let myself move on until each sentence was as close as I could get it. I tend to work on stories in that same manner. But then at the end, a different impulse emerged, I made a short list of scenes and started going to the Hungarian with a mission — I wanted to start ticking them off. The night before we moved to Brooklyn from the studio I was going to a friend’s birthday. I literally wrote the last sentence of the book with Marguerite Duras’s The Lover by my side while Jerome was hoisting our belongings into boxes, we popped a bottle of cheap champagne (the cork of which I still have saved), and I went out that night. I feared if I didn’t finish that first draft before we physically moved, the voice would not remain the same.

Q: That’s fantastic! It’s true, what a tenuous thing that grip on a voice can be… I know that first-to-third-and-back-to-first transition well. There’s this great Zadie Smith essay on craft that I have brought in for my students where she calls it OPD, or “obsessive perspective disorder.” She talks about spending months rewriting the opening twenty pages, switching back and forth several times a day, and in the end she says she always lands on third person past, as she is “an English novelist, enslaved to an ancient tradition.” So, I guess you are in good company there. Maybe just one final question, since we’ve touched on teaching and I know you are a teacher of creative writing as well. Your answers have all been so illuminating and instructive, and I wondered what kind of advice you like to give to students… your own, and others out there who are undertaking their own struggles to find a perspective or a voice for themselves.

A: Obsessive perspective disorder! Now I finally know what to call it! Thank you — I feared I was alone in my obsession, suffering paranoiacally.

Teaching is my life blood. I tell my graduate students, “teaching is an intercourse.” I truly mean it. It is the intersection between thoughts and ideas and human activism. I know you too understand this. The only advice I know about how to write is this: “Live with your heart open and lead with your gut. Don’t negate the complexity of your own human experience. The incongruities and inconsistencies. Those are the places to write from. Write down into something from which you yourself need saving.”