Interviews

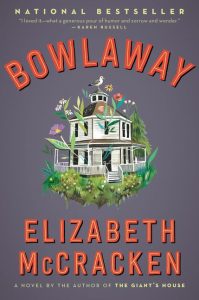

Elizabeth McCracken’s “Bowlaway” Is a Charming, Quirky Family Saga About Love and Bowling

The author on how women throughout history have adjusted to make space for themselves

Her first novel since 2002, Elizabeth McCracken’s Bowlaway is an epic generational story that doesn’t feel epic at all — instead, reading it is familiar, funny, alive. At the turn of the twentieth century, enigmatic Bertha Truitt appears in the town of Salford, MA, lying unconscious in a cemetery. When she comes to, Truitt by turns charms and astonishes the residents, insists she invented the game of candlepin bowling, and builds an alley in the center of town which — scandal of scandals — allows women to bowl. When Truitt dies in Boston’s Great Molasses Flood (which is real, and took place almost exactly a hundred years before Bowlaway publishes), she leaves behind the bowling alley, relatives with mysterious connections to her, and a town she changed forever.

McCracken pulled names from her own family’s genealogy, so in a way, the characters in the book are the author’s family, rooted both in fiction and in real life. And that’s how the novel feels — more fantastical than history, more workaday than a fairytale — with all the humble business of daily life: work, motherhood, military service, family duties. Truitt’s influence seems otherworldly and she belongs in concert with the best storybook mentors, like Mary Poppins or Willy Wonka. McCracken has the unique ability to be simultaneously delightful and heartbreaking, and Bowlaway leads us to examine the physical and emotional artifacts people leave behind, whether or not they touched them directly — bowling alleys, families, memories. She and I recently talked by phone about marrying the ridiculous with the tragic, how women carve out space for themselves, and the inherent humor of bowling.

Katy Hershberger: So, seventeen years since your last novel. How does it feel to come back to that form after short stories and a memoir?

Elizabeth McCracken: I think it feels alright? It has terrified me a little bit more somehow as the book comes out, I’m not sure why. And I’ve written novels in there, they just haven’t been any good. I just haven’t published them.

KH: Does it feel different from the last books you’ve published, even if they weren’t novels?

EM: Yeah, I think so. I think with the short stories, short stories are quieter publications, generally speaking. And the stories had mostly been published other places, so it didn’t feel like the first time they were being read. I guess part of it is this time I have more of that sort of panicked writer’s feeling of “what if everybody hates it? What if people really really hate it?” With the short stories I felt like plenty of people had read them. “Plenty,” that’s a ridiculous expression for short stories published in literary magazines. [laughs] I mean, plenty for me, I should say, but that’s not to say a lot. It felt like it had already been out in the world a little bit, and not so much with this. So I’m feeling a bit nervous.

I’m an Award-Winning Short Story Writer and I Don’t Know What I’m Doing Either

KH: The book is set in New England, where, you write that “even the violence is cunning and subtle.” I’d love to know about your background in New England and why you decided to set this story there.

EM: I’m a New Englander. Though it’s interesting, I’ve got an older brother who spent the same amount of time in New England as I did, but thinks of himself as a west coaster because we spent part of our childhood in Portland, Oregon. But I was born in Boston and moved back there when I was about seven and a half. And then in 2010 I moved to Texas and it feels like a different country to me. And whenever I go back to Boston, sometimes people are rude to me and I think “Oh my gosh, people are really mean here” and other times people are rude to me and I think “It’s home. I love it. People are so mean.” I saw a woman be spectacularly rude to a pair of men who were trying to buy admission to the Pilgrim Monument in Provincetown a couple of weeks ago. She was — appropriately — monumentally rude to them. My husband, who is English, was horrified and I just went “No, she’s quite right. They’re too late and it does my heart good to see her deny them admission.” And she was awful. They said, “Can we possibly?” and she went “No!” She took a really long time to explain the monument was closed. She just took great pleasure in saying no to them, which I do feel can sometimes be a New England-y trait.

KH: So it’s a far cry from Texas.

EM: It’s a far cry from Texas where people are usually really nice and helpful. I wanted to write about a place that felt like home because Texas, which I enjoy, I don’t think will ever feel like home. And I don’t think Texans will ever consider me as being a Texan in any way. That is my experience of Texans. Texas is the only state where I’ve heard people say, “I’m a sixth generation Texan.” Maybe they do that in California too. You might slightly brag about your family coming over on the Mayflower in Massachusetts, but certainly I’ve never heard anybody say “I’m a sixth-generation Massachusetts-ite,” person, whatever. We don’t even have a noun for it, that’s the thing, there’s not even a noun for somebody who comes from Massachusetts. But yes, I was missing New England.

KH: It feels like such a New England story, between candlepin bowling and the Molasses Flood, and that it has to be really rooted there.

EM: I can’t quite remember when I landed on candlepin bowling, but pretty early. And then I was delighted when I suddenly realized that the math would work to put in the Molasses Flood.

KH: The flood feels especially perfect because it’s a sort of slightly humorous and ridiculous married with the tragic. It feels like it fits in so well with these themes throughout the book.

EM: If I had a sweet spot that would be what I’m attempting to achieve in my work, it would be that. Slightly ridiculous but also tragic.

If I had a sweet spot, slightly ridiculous but also tragic would be what I’m attempting to achieve in my work.

KH: Bertha to me feels very much like a timeless, mythical character like Mary Poppins or Willy Wonka. This sort of storied mentor who doesn’t quite belong in ordinary life. I’m curious if she was based on anyone in real life or in fiction, and how you came to write her.

EM: She’s not based on anybody who I know in real life. It’s interesting because I only realized this recently. She’s a cousin to a character in a novel that I really love by Susan Stinson called Martha Moody. And I realized that Bertha Truitt is a name from the grandfather’s genealogies. I think she naturally came to be a cousin to this character from this novel, which is out of print and it shouldn’t be, it’s so beautiful. It’s about a woman who founds a town called Moody.

KH: So it seems that there’s both real life genealogy and fictional genealogy throughout the book, is that right?

EM: Yes. Yeah.

KH: I read that the names of the characters were inspired by your grandfather’s genealogies. How did that come to be? How are you inspired by the work that your grandfather had done with your own family?

EM: I essentially just went through this genealogy that he had written in the sixties. It’s quite big and thorough. He was a professional genealogist and editor of a magazine called the American Genealogist for quite awhile, and I just took names out. I just popped them right out. I don’t think any of them are close relatives, but they were so evocative to me that I just, I had a giant list of names that I looked at for awhile and then started to put them into fiction. The first two I had were Bertha Truitt and Dr. Leviticus Sprague. I can’t tell you who those people are, who those people were in real life anymore. And actually l think sort of instantly I couldn’t. I just wanted to think about the names suggested. But overwhelmingly the names in the book are names from the genealogy and only begin to break down when people got married and began to have children and I was like, oh I can’t do that anymore. But somebody named Betty Graham who was known as Cracker is from my grandfather’s genealogies. The names Luetta Mood, Hazel Forest, Leviticus Sprague, Joe Wear, Jeptha Arrison, those are all from the genealogy.

KH: So in some ways every character in the book is a part of your family.

EM: Yeah, I guess. Yeah, I suppose.

KH: Genealogy and legacy seem to be themes that you come back to in your fiction. How do those themes inspire you and what did you want to say about genealogy and legacy here?

EM: That’s interesting. Part of it is because of my grandfather is something that I was really aware of, especially on that side of my family, the McCracken side. In one of the genealogies he actually talks about how he’d intended to do my mother’s genealogy, I don’t know if that’s really true, but because my mother’s side of the family is Jewish it’s much more difficult to do a thorough genealogy. And certainly when I was growing up, that side of the family told a lot of stories about family and they also told a lot of stories about people they couldn’t quite figure out who they were.

There was a photograph of two children who my cousin Elizabeth, who is my grandfather’s first cousin, often was talked about with a great deal of mystery. She thought that they were a brother and sister who had died in Europe before the family had come to Iowa in the 19th century. And so I think I was always really interested, as I tend to be in any topic, in how it was true that genealogy was interesting but the opposite of that is also true. That it’s both important and not important. That blood relation actually doesn’t mean that much except for it often does to people. And I think I’ve always found that interesting.

KH: It’s more about the meaning you put onto the idea of family than the actual blood connections.

EM: Exactly. And those questions of what difference does it make, what difference could it possibly make if you were related by blood to somebody. My brother has actually gotten extremely into genealogy in the past couple of years and has actually found out an enormous amount of stuff about my mother’s side of the family that we never knew through his research.

KH: I think it’s so interesting that a lot of the book is about the duty of being part of a family, whether or not you’re related by blood. From the flawed but devoted mothers and the difficulty of motherhood to sometimes being stuck in the family business. Could you talk a bit about your take on those sort of expectations that can be bound up in family?

EM: I wrote another book in which having to go into the family business is a big deal though in that case the person didn’t, and I have no idea why, since certainly that wasn’t any kind of obligation I ever had. Even though I say that from my campus office at a university and my parents were both university employees all their lives. I’m not sure. The question of duty is one that I’m always really interested in. I write about it and I don’t know why! Sometimes I have an automatic answer to that question. The answer might have to do with always being interested in the family stories on both sides of my family, to think about the people whose lives are changed by being dutiful. By staying at home, serving another relative, whether it was a sibling or a parent or a child.

KH: There’s so much in the book about the role of women throughout history and having to carve out a space for oneself. Given what’s going on in American culture right now, was it a goal to write a feminist novel?

EM: I almost never have a goal in my writing but anything that I’m thinking about in my daily life goes into the back of my brain and hopefully comes out through my writing. And I, like everybody, I’ve been thinking about these questions. About how women have adjusted themselves through history to make space. And the ways in which they’ve been quietly and automatically ignored. And ignored by people who don’t even realize that they’re doing it, including other women. It’s something that’s been very much on my mind.

You know, I teach with undergraduate and graduate students and with the graduate students I’m interested in the way the women writers are taught to think about themselves and the importance of their work versus the way the men are. If I’m giving advice to a woman who’s trying to figure out what to ask for or how to approach an agent or how to approach a job, and women are often afraid to ask for things, and I always tell them, well think about being a man, and if a man would ask for that thing then you should ask for it. And you should know that what that means is that you should ask for it, it’s not that men are being outrageous in asking for it, it’s something you should ask for.

If I’m giving advice to a woman who’s trying to figure out what to ask for or how to approach an agent or how to approach a job (and women are often afraid to ask for things), I always tell them, well think about being a man, and if a man would ask for that thing then you should ask for it.

KH: I of course have to ask about bowling. I love the way that you describe bowling and say “our subject is love because our subject is bowling,” and that “it’s possible to bowl away trouble.” I wanted to ask about your connection to bowling and why you equate it with love and solace.

EM: I was a childhood candlepin bowler. And also I now have kids, and if you’ve got kids in America you will end up in a bowling alley eventually a couple of times a year. In Texas it’s tenpin bowling and I think when bowling re-entered my life when I was a parent it made me really miss candlepin bowling because it’s less brutal. Narly anybody can pick up a candlepin ball and roll it. And I really loved that and it’s also a regional variation and I was missing home, so I missed candlepin bowling.

I also just think everybody knows that bowling is an inherently funny sport, I don’t know why that is. I don’t know if it’s cause it’s an indoor sport, you don’t necessarily have to be fabulously fit to do it or to be really good at it. I discovered as I was researching the book it’s kind of mesmerizing to watch bowling even though there’s a really limited number of outcomes to bowling, especially candlepin bowling. There’s never the threat that somebody’s going to bowl a perfect game. And because bowling is inherently funny I love the idea of writing about it as being a romantic thing to do. And I do find it kind of strangely beautiful.