Interviews

Growing Up in a Chinese Restaurant in Atlantic City

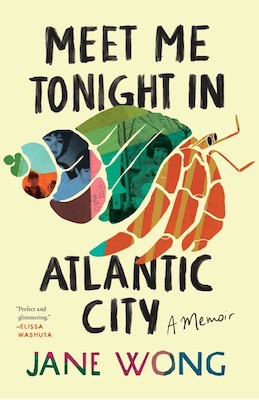

Jane Wong confronts toxic masculinity and finds nourishment amidst pain and rage in her memoir "Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City"

Jane Wong’s memoir Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City is a feast of a book. It’s about hunger—the hungers of the body, of addiction, of history. Brilliant, gutting, and funny, she writes with such range about growing up in her family’s Chinese restaurant in Atlantic City as their reach for the American Dream slips away.

Wong recounts not only what it was like for her immigrant parents to have had a restaurant, but also the importance of appetite, and the long painful shadows of family surviving and not surviving Mao Zedong’s Great Famine. Wong’s love of food, her father’s love of gambling, her mother’s unconditional support and love, and the abusive love of men are intricately woven together, offering a meditation about love itself.

I sat with Jane Wong over zoom to talk about finding nourishment amidst pain and rage, the incantatory power of poetry, and the intimidation tactics of toxic men.

Ingrid Rojas Contreras: You begin the memoir with eating dragonfruit and you end with eating mango. Your mother is in both of those scenes as well. I was moved by the connections you were making between the Great Famine and your ancestors experiencing hunger, and feeling voracious in the present, and the importance of, you know, eating more than the ex-boyfriends and having a larger-than-life appetite. So that eating and tending to your hunger seemed like radical acts and important in your lineage.

Jane Wong: I feel like it is radical. If anything, you know, I worry sometimes—there’s times in the book and also in real life in which life will get so busy and so hard, I will not nourish myself very well.

I’m so lucky to have a community that feeds me, which in a weird way, like you’re suggesting, I feel that I consume in order to take care of the ghosts. Parts of the memoir also speaks to what it means to finally get to a place where I can sustain myself too.

IRC: For some of us, the historical archive has been interrupted—either because of our “unimportance” to history, or because of war and migration. So then when people like us are writing memoir, we end up having to reach for these other versions of archive. There’s this great passage in your book where you’re making jook and describing the recipe. Since it was a recipe that’s passed down, that felt archival to me.

JW: I never thought about it in that way. That’s so thoughtful. A soupy archive! I love that. Obviously these foods are tied to our deep, deep, ghostly archival selves.

IRC: What I love about our conception of archive is that it allows for a communication with ancestors.

JW: Yes! One thing I was thinking about with the ghost archive has to do with this one section in the memoir where I made one of my poems into sculpture. I had pineapple cakes on the altar, which are archival, and the favorite snacks of my grandfather. Someone stole the pineapple cakes or they went missing and the security guards couldn’t figure out what happened. I absolutely loved that, because then, literally the ghosts took back the archive. I feel like the ghosts kind of want their stuff back, which is kind of funny, and it makes sense to me. It’s their stuff.

IRC: Yes! It’s a porous relationship. There’s a popular conception of the archive as static. It exists in the record and you read it and that’s it. But a ghost archive is a conversation, things are offered, retrieved, taken back.

JW: And it involves deep, deep listening. I’m sure you encountered this, too, but, it’s nearly impossible to interview family. It’s not the work of a journalist. It feels like archival work. It’s putting your ear against like, literally, the graveyard.

That was a big part in my own writing through the Great Leap Forward. It was honoring the fact that my family would not, cannot speak about it. It is too painful. I didn’t even try to ask them fully because, I knew it would be crossing a line that was not okay. So then you do deep listening and you listen closer to the stories told around you. It wasn’t until my grandfather was very, very ill, for example, that I found out that he was adopted and his father who adopted him committed suicide.

That happened a lot actually during that Great Leap Forward when families were gone. People would adopt and say, “You’re now my family, you exist, you’re alive.” So, again, no one told that story.

IRC: The other thing about writing into those silenced histories is that then your story starts to speak for the other silenced histories. I’ve met so many Colombians who are born in the U.S. who have said to me, “My parents don’t talk about the reason why we came or what happened, but your book gives me an answer.” It can be so powerful for everyone in the community to hear those stories because everyone else has been living in that silence as well.

In moments of rage, you have to care for yourself and you have to reach out to others to care for you.

JW: The question I get asked often is how did I talk to my grandparents about the famine. I guess the answer is I didn’t. What I usually tell writers and audience members is that what’s more important for me is taking care of my elders and giving them the peace they need.

IRC: And that’s the difference, isn’t it. Some memoirists have this idea of interviewing as extracting information or extracting story from someone and that is a very colonial perspective.

JW: It is. You’re totally right.

IRC: What our communities need is not extraction but listening, and as you’re saying respecting the silences people want to keep especially when they’re for their own survival. The caretaking of those silences is so important. Even writing the silence says so much about the weight of something that’s happened.

The stories you wove together felt like a collection of things that are nourishing and things that are exhaustions.

Because your family had a restaurant, there are the literal ways in which you’re finding nourishment, and then there’s the metaphorical nourishment of poetry. And there are the elements that I would categorize as being exhausting to the self, which in the memoir are problematic men, toxic masculinity, gambling addictions.

JW: Oh, yeah. There is a lot of rage in the book. In thinking about being an Asian American woman, I am not necessarily expected to be rageful, or to say anything, truly.

And rage alone is very different from being rageful in community, and what that can do in terms of nourishment and tangible change. I think about that a lot, and especially even just thinking about the relationship between me and my mother, which is so central to the book.

There’s a lot of humor in our relationship, as much as there is this kind of deep sense of sharing our exhaustion and talking about our exhaustion.

What’s really been powerful for me over the years is that when I finally shared with my mom what happened in terms of a really toxic, abusive relationship, she began to share about my father. That’s something that she really protected me from growing up. I have forgiven my father in terms of other aspects about who he is, such as the gambling and such as him not necessarily being in my life and missing out on our family. And I miss him. I really hope that he’s well and I think about him all the time. But when my mom started sharing more about him in terms of being a husband, that I had to work through. That was newer to me.

In writing memoir, you almost kind of have to have a reckoning in the process of writing the book, and tell the story like you actually are actively inside the living organism of writing this thing. That was surprising to me. I didn’t necessarily expect it. It was definitely the hardest thing I’ve ever done so far.

IRC: There was this one part in the memoir where you mentioned writing a poem before leaving this abusive relationship, and how the poem was you in the future and how it emboldened you to leave. Is that a practice that you’ve always had, trying to see yourself into the future by writing?

In thinking about being an Asian American woman, I am not necessarily expected to be rageful, or to say anything, truly.

JW: Absolutely. I feel so small sometimes in terms of all these things that have happened to me, and I feel like poetry is sometimes the only space in which I have agency or a voice, quite literally; what it means to be a speaker in a poem. In many ways I do feel like it is my most powerful version of myself and I do tend to write in order to make something happen. I think that if there is any goal I have when I’m writing, it’s starting a poem not knowing where I’m going to be by the end. But usually by the end there is something incantatory, something that’s desired that I didn’t begin with.

Maybe it’s kind of like you already know the answer. You know what you need to do and you just have to express it and then then do it.

IRC: That sounds powerful, to write into a desire to do something for yourself. If the desire was not loud enough before, then writing it would give it volume. The moment that a desire has volume, then you’ve propelled yourself into it. I love how it’s conjuring something into being.

JW: For me, words were kind of one of the ways in which I feel like I can make change happen. Especially with the Bad One who’s in the memoir.

I really, really did need to write that poem, and a few others, in order to remind myself that I had agency and that I had a voice, and that these last two are actually something that a lot of these toxic men did not like about me.

That’s the other thing that I discovered and tried to unravel in the memoir, especially in the chapter called “The Object of Love”—I wanted to reckon with the fact that here was the one thing that gave me so much power and agency which is writing, and here where these very toxic exes of mine who really did not like the fact that I was a writer. That has always been, unfortunately, a pattern I’ve noticed.

IRC: I found the way that you were writing about abusive relationships and patterns to be masterful. I loved what you were saying about the term “daddy issues.” In the memoir you wrote about how being at the receiving end of all of these abusive behaviors has consequences, and how our term for those traumatic residues are “daddy issues,” which is a term that minimizes the harm a person has been subjected to, and minimizes the traumatic response to that harm.

JW: Yeah, and, you know, that term is so deeply gendered, how it’s often used. I write about it a little bit in that particular chapter: who gave this to me? Why did this happen? Why did this happen to me? Why was this toxicity placed upon me?

In writing this book, it was really difficult to wrestle with a lot of internalized racism too. I had that feeling in your stomach where you’re going down a rollercoaster and it’s half in the air. It’s just a little icky, and what to do about the white ex-boyfriends in particular. But I think that I had to go there, and if I didn’t, I was going to regret it.

I’m curious, too, about how audiences have reacted to your work. The memoir work is to say these are our stories, these are our lives. But also I always wonder, you know, what did white audiences expect going in? I’m curious about that in terms of the expectations.

IRC: That has been fascinating to see how different audiences react to the book. Early on, a white man told me that he was an EMT and that he knew exactly what I meant when I said that things get very strange when you get close to death, witness it, are surrounded by it. I wasn’t expecting that. Many people connect to the love in my family, and my relationship with my mother. I did have a white woman tell me that she loved the book and she only had one qualm, which is she wanted me to say my grandfather was a shaman and she didn’t want me to use the word curandero.

But one of the things that I wanted to say in terms of the way that you were writing about abusive relationships and surviving and getting out of those, is that I think that’s why the anger and the rage in the book felt so good to me as a reader. There was this magnificent energy that lives in the book and that is all about occupying an angry space, and honoring that emotion.

Poetry is sometimes the only space in which I have agency or a voice, quite literally.

JW: With those bad relationships, I always think to myself, you can’t make this stuff up. I’m like, “What in the world?” For example, my ex-fiancee sending me an invoice for the mattress.

IRC: You wrote that he had possibly slept with other people on the same mattress and the mattress was blood-stained. That was why he was sending you the invoice, but he couldn’t even prove that it was your blood.

JW: Yes! And so, again, when your system is so shocked by moments like that, when you actually receive an email like that, how do you not feel not just rage, but a deep sense of fear, too, because that’s obviously an intimidation tactic. And what can I do except attempt to nourish myself?

In moments of rage, you have to care for yourself and you have to reach out to others to care for you, and vice versa to care for them when they get whatever email that they get, which always unfortunately happens.

It’s this cycle of care that I’m really grateful for. In the book, my mom calls it fertilizer. And it does feel like that. It’s like I’m always trying to make some sort of elixir of care metaphorically, but also literally in terms of taking care of my plants, of which I have like 75.