interviews

INTERVIEW: Susan Straight, Author of “Highwire Moon” and “Between Heaven and Here”

Susan Straight is an anomaly. She has published eight novels and two childrens’ books. She has won the Edgar Award, been a finalist for the National Book Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Award, and most recently, she received the Kirsch Award for lifetime achievement. Aside from two years at graduate school, she has managed to achieve all this without leaving her hometown, Riverside, California. In fact, she can see the hospital where she was born from her kitchen window. She jokes about it, saying that her daughters had to put paper over the window so she wouldn’t stare, which is funny but also troubling.

Riverside sits in chaparral country, where tumbleweeds roll through dusty lawns and palm trees mark the boulevards. I met with Straight on campus at the University of California, Riverside, where she is a Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing and the director of the graduate program.

At one of your readings, you said that A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was one of the main inspirations that led you to leave Riverside. Is that true?

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn made me think, “Oh, to be a writer, you have to go to a place like Brooklyn, sit out on a fire escape, live above a restaurant — live this really intense urban life.” I thought that I had to leave Riverside, and I did when I was done with USC.

There was this whole New York thing, too. We used to ride the bus, my husband and I. We would go down to Manhattan, stay in the Flower District, in somebody’s loft and just walk around New York. And this was around the time of breakdancing and rap music, and it was really different for us, because we came from a completely different kind of Black culture in Riverside. And here we were in New York, where everything looked so different. That was a big deal to me, because it made me write about home. I started missing tumbleweeds and palm trees and chain-link fences and graffiti. And I really missed our friends back home. So, I think that’s when I started writing the stories that were in Aquaboogie, and actually I wrote the beginning of Highwire Moon, too.

Do you think that’s common among writers, that they have to move away from home in order to write about their hometown?

I think everyone is completely different, and there are absolutely two different schools. I think that some people go away, and they reinvent themselves. They move to Brooklyn and they write about Brooklyn. Or they move to L.A. I mean, David Ulin wrote this great essay about Joan Didion. He was from New York, moved to San Francisco, read Joan Didion, and now he’s Mr. California writer. And that is so fascinating to me. But then there are some others of us, who carry these seeds of home, always. And I had not really understood this until I got to Take One Candle Light a Room. A character says her mother never forgave her for moving an hour away to Los Angeles. And it’s true, and then she said that her mother’s reaction taught her the phrase that I use now at a lot of readings. There are two kinds of people in the world: people who leave and people who stay. And I’ve given this talk all over the country, and I’ve asked people in the audience, how many of you were born within an hour of where you live now; how many of you live more than an hour away? And then at three separate readings, people came up to me and said, “But there’s a third category.” And I said, “What?” And they said, “People who leave and then come back.” And I said, “Oh my gosh, you’re right. We are such a particular brand of losers. How could I have overlooked us?” So now I have the third category: people who left and then came back. Loserdom. That’s me. I like it.

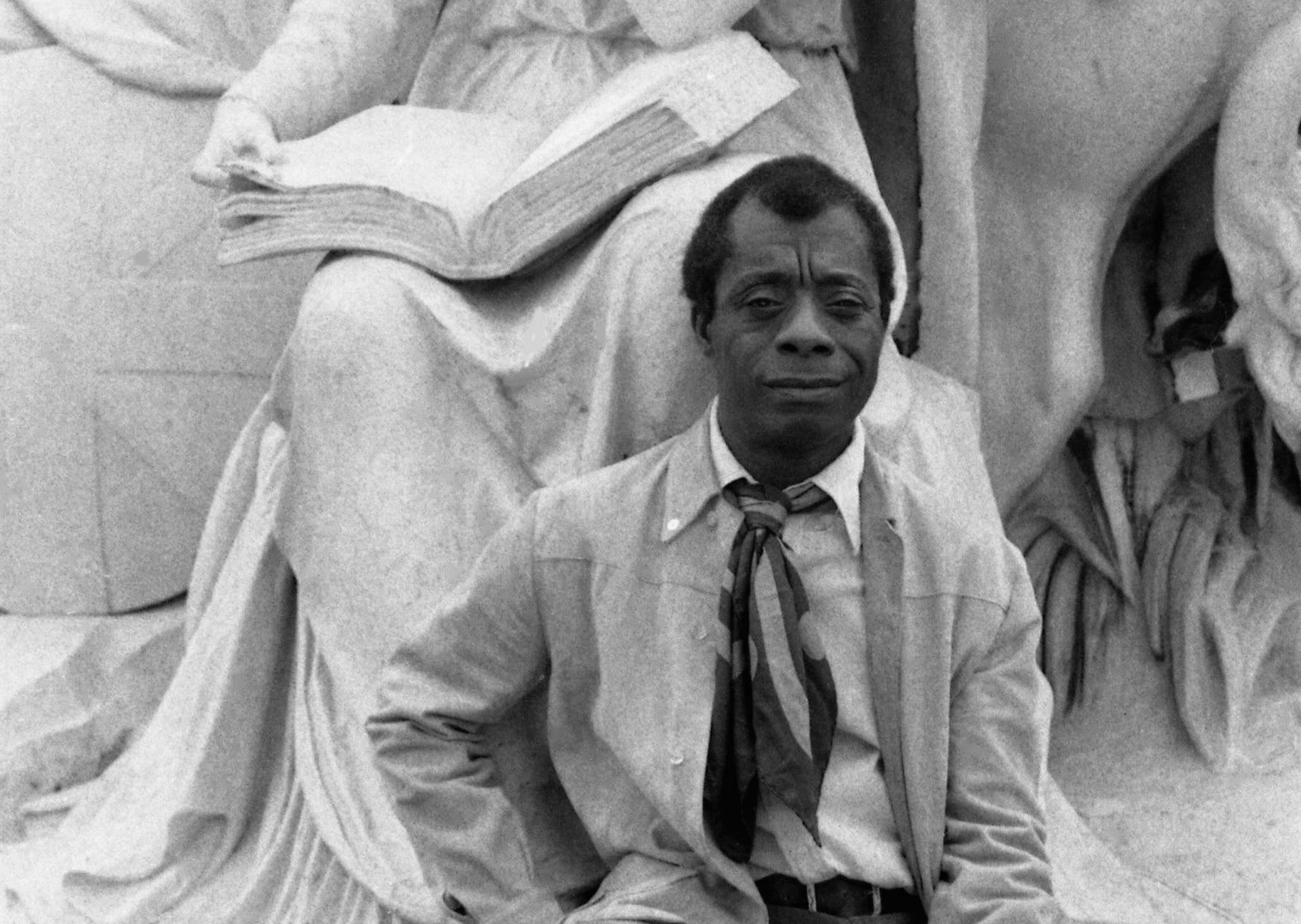

You mentioned that every young writer needs early help from a mentor, the way that Baldwin and Neugeboren gave you direction. After receiving the Kirsch Award, do you still look to your peers for guidance, or do you feel as though you can guide yourself at this point?

Going off to UMass, I met James Baldwin and Jay Neugeboren, and that really did transform my writing life. Jay Neugeboren taught me to line edit my stories. The first story I turned in to him, he said, “This is a great story, but it starts on page five.” I was just — you know how we are when we’re young writers — we’re like, “What? Those first five pages are faceted jewels.” That’s what I was thinking, like, what? I can’t get rid of those first five pages. And he was just like, “Yep, just cut them.” So, I remember thinking that that was how you have to look at writing. You have to get direction from someone.

James Baldwin taught me about secondary characters. I always say that — that James Baldwin had looked at a story I had written about a girl on the bus. And he said, “The heart of the story is when she gets to work and she talks to Lenard.” And I looked at him, thinking, “What on Earth is this man talking about? That is a little tiny moment in the story, and the character of Lenard was this tall black guy who was gay, and he was balding, and he worked with this young 19-year-old.” And it took me until I came home to Riverside and was working at Job Corps and trying to write these stories.

There were things that James Baldwin and Jay [Neugeboren] said to me that I didn’t understand until five years later. But that’s why you need a great teacher like that. Now I look at secondary characters as the absolute key to everything I do. And it was because James Baldwin had said that to me all those years ago: to pay attention to who you think are minor characters. They hold a lot of the answers.

At this point, I show all my work to my best friend, Holly, whom I met in graduate school. I just showed her the first hundred pages of my new novel. We still trade after 30 years. She’s the one who is really hard on me and says, “Nope, there is no way that she would do this. There’s no way that Cali would ever say this to someone.” And she’s usually right.

You have said that you carried around the characters from your Rio Seco trilogy for 15 years before you were finally able to finish the last book of the three, Between Heaven and Here. Do you need something to knock loose with a character or particular story before you feel comfortable writing about it?

Every day to get here, I drive past the house of someone who is 70-something years old, almost 80, and this person was the product of a rape. And I’ve known this person — you know, he’s someone whom I respected all my life, and this was something that I heard told to me twice in two sentences. And every day, I see this person and wave. And I always think about the life that this person’s led and all the children he’s raised. And those are the things that are hard to write about, because they might be something that you have to carry around with you for awhile to be able to imagine. And that’s what young fiction writers often are not willing to do, or they feel like they don’t have the time to do, because the culture is different now. You’re supposed to be selling something, and you’re supposed to be posting on Facebook, and you’re supposed to be writing things all the time. Think about Alice Munro and the old way that you walked around and thought about something, you know? And think about how long it took to produce something. It’s a strange antithesis to modern culture right now. But for me, I’m in my car, driving around and I’m thinking, or I’m hanging out with people who are 80 and 90 years old. There’s a sort of slower rhythm to my day, because I live here. I’m not in the city.