infographics

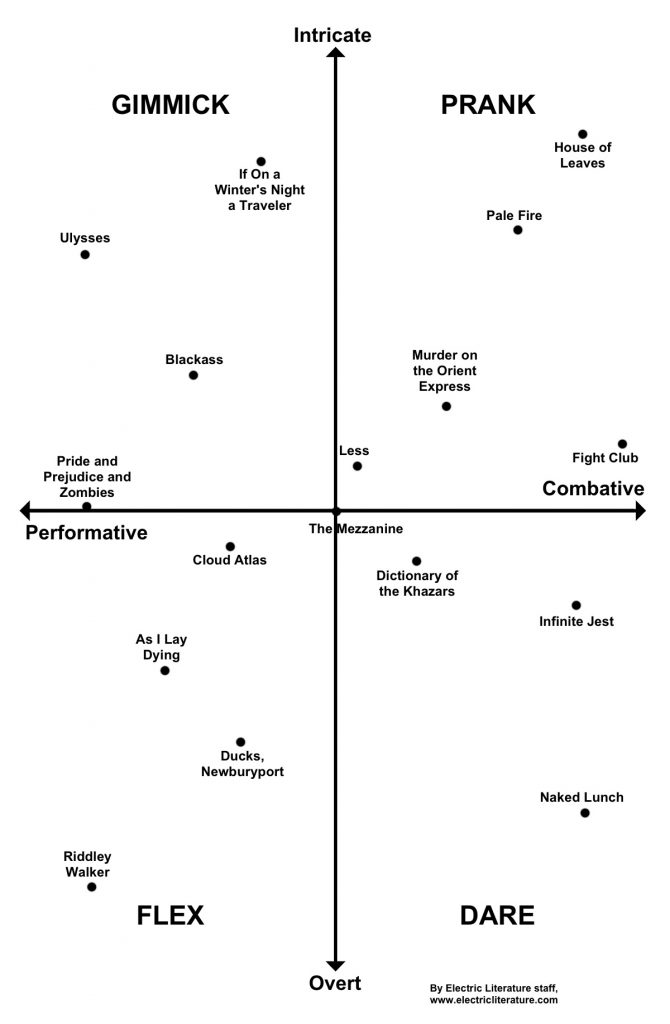

Introducing Electric Literature’s Literary Stunt Index

A scientific method for categorizing gimmicks, pranks, flexes, and dares

It’s hard to grab a reader’s attention. It always has been. Sometimes, to generate a little buzz, a book has to be something a bit more than a book. It has to be a stunt, some kind of feat or achievement or goof that gets people talking.

There are many ways for literary work to be a stunt, and after much discussion, our intrepid Electric Lit staff has developed a matrix to map out the four basic kinds of literary stunts: gimmicks, pranks, flexes and dares. The underpinning behind each of these quadrants is explained below, and we’ve plotted some example books on our matrix to further illuminate each section.

Our intrepid staff has developed a matrix to map out the four basic kinds of literary stunts: gimmicks, pranks, flexes and dares.

The study of literary stunts is fledgling, and we understand there might be some readers who disagree with us; we welcome such disagreements. To move us closer to a unified theory of literary stunts, we need a variety of feedback. Therefore, if you have a quarrel with or addition to our matrix, we encourage you to reach out to us. If you’re especially persuasive, we may even update the chart.

For your consideration, Electric Literature’s Literary Stunt Index. We’ve plotted some notable books and some of our personal favorites to give you a sense of how it works.

Glossary

Gimmick: A gimmick book has, above all, highly a pitchable (if not necessarily commercial) concept. Here are novels you can easily break down into a one-sentence logline, designed to evoke an “Oh, interesting” or “Huh, neat” from the potential reader. i.e. It’s the Odyssey, but in Ireland; it’s a romance novel, but written entirely in Dothraki; it’s Pride and Prejudice, but with zombies; etc.

The concept behind the work is intricate in order to hook the reader, not to antagonize them; put another way, it’s high-concept for the sake of being engaging, rather than challenging. (It can be challenging, but that’s not the point.) This isn’t to say these books can’t be great works of art, just that there’s a bit of shtick to each of them. But hey, at least these are honest about it.

Prank: A literary prank is interested in making a fool out of itself so it can make a fool out of you, too. The book is a joke played on itself, and therefore played on anyone who reads it: You thought the work was one thing when it is, in fact, a different, much sillier thing. Many of the examples on our Matrix involve plot twists, of a sort, but not every book with a twist is a prank—only ones where the twist subverts the very idea of the novel or genre you thought you were engaging with. “How foolish of you to try and solve this whodunnit,” Murder on the Orient Express seems to say, “because it’s EVERYONE who done it! Haha, clever, no?” Well yes, but also, come on, man, really? That’s not—those aren’t the rules. I thought we had. I mean I thought we had agreed on some rules. But it’s fine. No, really, it’s. Fine. Okay, yeah fine, I guess I read that, yeah, sure. You got me. Fine, no, it’s fine. I get it. I see what you did there. And it’s cool, that you did that, I guess. To this book, and also, to me, personally. Sure. Fine. Yes.

Flex: A literary flex is notable because the author pulled something remarkable, or at least so unusual that no one else has ever done it. It’s flashy, it’s interesting, and it may or may not be difficult for the reader to grapple with, but the reader isn’t really the point—the writing of the thing is the point. Sticking the landing on a completely wild idea is the point. A flex displays the height of an author’s powers in an over-the-top way; at its core, a text that qualifies as a flex seems to say “Look what I can do,” and then does it.

A text that qualifies as a flex seems to say ‘Look what I can do,’ and then does it.

The end result of a flex needn’t be extraordinarily long or complex. The only real requirement is that the writing of the work was transparently difficult to pull off. To use an example that isn’t a novel, consider Annie Baker’s translation of Uncle Vanya. Translating a century-old work is tricky, sure, but it’s done often enough. What isn’t done nearly as often is someone taking on a play thoroughly enshrined in the theatrical canon and then producing a more accurate, human version of the play’s text. Baker opting to take on, and subsequently succeeding in such a task is an enormous flex.

Dare: A literary dare is a work that you don’t believe is actually someone’s favorite book, even if they swear up and down that it is. A dare does not want to be your favorite book. Literary works that qualify as dares are needlessly confrontational, chock full of obstacles to the reader actually understanding or working their way through the text. Here is a book with a dozen different maps in the first of its four indexes, or a story overflowing with footnotes, or a novel that requires an awful lot of skipping back to earlier pages to double-check you’re understanding what it is you’re actually reading. You can’t let your mind drift for even a moment while reading a literary dare, or you’ll completely lose track of what’s going on and have to jump back some ten pages or so just to catch up to yourself. If a flex book is the writer saying “Yeah, I wrote this,” then a dare is something that makes the reader just as smugly declare “Oh, yeah, I read that.” It is a challenge to take on and a brag to claim to have completed it. And most of us won’t believe you when you say you understood it, anyway.

Methodology

X-axis: From left to right, our X-axis is graded on a scale of “performative” to “combative.” This is essentially a scale of aggression: how much is the book seeking to entertain vs. how much it is seeking to confuse, mystify, impress or befuddle? Hence why both “Gimmick” and “Flex” find themselves on the performative side of the scale. A flex is inherently a performance; if someone publishes a thousand-page sentence and no one is there to read it, is it really a flex?

The combative side of the scale, then, are for works of literature that create discomfort in the reader (and possibly the author) for the sake of pulling off the stunt, whatever the game of the book may be. This discomfort can be built into the structure of the book (extensive footnotes, jarring shifts in point of view) or its content (whether it be tedious, violent, discomfitingly erotic, etc.). Any stunt book that can be described as “needlessly confrontational” belongs on the right side of our matrix.

Y-axis: Raging from “overt” at the bottom to “intricate” at the top, we suspect this is the part of the matrix that will garner the most ire from fellow readers and stunt-scholars; we ask that you allow us the room to explain. It could be argued that almost any concept that can be labeled a “literary stunt” is inherently intricate. If it wasn’t somewhat convoluted, one could argue, then it wouldn’t be a stunt. But that’s precisely why this gradient is here: all of these concepts have already cleared a minimum bar to be considered “stunts.” Here, now, we can grade these works against their peers in show off-y literary exploits, and not on a scale starting with See Spot Run as the basement.

It could be argued that almost any concept that can be labeled a ‘literary stunt’ is inherently intricate.

We’re also considering the complexity or directness of a work from two different angles: difficulty for the author to thread the needle, and difficulty for the reader to understand what’s going on in the work. The latter consideration is why pranks are on the “intricate” side of the axis: even if the book eventually unravels itself, a prank must inherently keep the reader in the dark about its true nature until it’s too late. (Successfully bamboozling the reader also takes some doing on the author’s part.) And even if a gimmick is apparent on its face, or even in its title—looking at you, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies—the complexity required to pull such a thing off and still engage readers and still be considered ~literature~ is significant. By that same measurement, a flex might well be intensely complicated to pull off from a writing standpoint, but like an athletic stunt, the writer has to make it look easy—or at least make what’s happening clear enough for the reader to appreciate what they’re witnessing. And a dare isn’t a dare if you can’t understand, at some basic level, what you’re getting yourself into.

Conclusion

Even after laying out our terms and methodology, you may still disagree with us: with our categorizations, with our methodology, with our grouping these works of literature—many of which are beloved, cult classics, just regular classics, and/or our faves—with a term as trite as “stunt.” That’s fine. You are welcome to quibble in private or in public, the latter of which will do nothing but help our engagement numbers across our various social media platforms. Either way, we feel confident in our assessments. We have science on our side.