Books & Culture

LITERARY ARTIFACTS: The GutenPad Bible

by Kristopher Jansma

The Outlet is pleased to announce the arrival of a new column. Each month in the Literary Artifacts space, writer Kristopher Jansma will write about his encounters with rare books, writerly memorabilia, and other treasures in New York City and around the world, hoping to discover how the internet age is changing the face of literature as we know it.

It is the summer of the eReader. At a beach recently I saw one blanket after another weighed down by Nooks. My companions had each brought a Kindle, and all three marveled at how easy they were to read in the sun. Stubbornly, I squinted at my paper copy of Moby Dick, pointedly underlining and dog-earing its pages. And yet I was fascinated as the Kindles’ screensavers faded from Woolf to Poe. Then I smirked when our host lost his Kindle for several hours, only to find its slim profile hidden beneath my mammoth Melville.

For months I have been vacillating between loathing to lusting. Friends in publishing tell me that the eBook is saving the industry! While hardcover sales are down 23%, and paperbacks are down 7.7%, eBooks are up 80%! No one seems sure if they are the cure or the disease, just that they are the future. Others exclaim that they read so much more now that they can get any book they want, whenever. Good thing, too, as Borders is shuttering its last stores and Barnes & Noble is looking for a bailout. I worry that soon print books will be fetish items for the quaintly outmoded — like vinyl LPs (or CDs, even!) after the fall of Tower Records.

Since I was young, I’ve stopped in bookstores and stuck my thumb in the J-section where my own book would someday go. This summer, after I sold my first novel, the question my friends asked me most often was: “Are they going to do an eBook?” I’ve been threatening to sign all their Kindles with a steel-tipped quill.

This week, I decided to go and spend a little time in the presence of the world’s oldest book: The Gutenberg Bible. You might say I had a few doubts to work through. You see, all summer I’ve been straying from the path of the printed word; I have found myself running my fingers over e-ink screens. Tempting serpents have lured me into Apple Stores. I confess, I’ve been coveting my neighbor’s iPad.

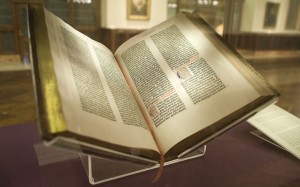

It was time to seek a higher power, so I made my pilgrimage to the Morgan Library in Midtown Manhattan, an American Mecca of ancient and rare books. There, in the huge private library of John Pierpont (J.P.) Morgan, sits his crown jewel: a complete Gutenberg Bible, one of 21 surviving copies. Kept under glass and guarded against photo-takers at all times, the Bible sits impressively open. Three feet wide, its forty perfect lines are adorned with gilded capital letters and colorful margins. I could see its stretched brown leather cover, so thick that its edge is also painted in golden designs. It looks to be worth every penny of the $35 million dollars it is estimated to cost — which seems only right for the most important book in all of Western Civilization.

I say the most not because it is the central text of a major religion (though it is that, too) but because it is the first book ever printed. Standing there in its presence is a holy experience in more ways than one. When the first Gutenberg Bible reached America, gentlemen were asked to remove their hats in its presence.

Before the year 1450 and Gutenberg’s printing press, every book had to be hand-copied in medieval scriptoriums, which took weeks, even years. Books were extremely rare, and pricey. Ancient libraries had to chain down books on public display and only lent them out if a reader left sufficient cash, or a book of equal value. Gutenberg’s machine changed all of this by dramatically speeding up production and drastically reducing the price. Information suddenly could be spread easily, and poetry, holy texts, philosophies, and fairy tales could at last be owned by the common reader.

As I stared down at the thin, wavy pages inside the glass case, I was struck by the irony for the first time. This book represented a revolution that led the world out of the Dark Ages and into the Renaissance. Cheaper and faster, the ideas of mankind could reach farther; they could go forth and multiply. And yet I could not touch the book now. No visitor at the museum could flip its pages. What good is a book that can’t be read? What if I didn’t happen to live in one of four cities in the world with a copy on permanent display?

Well, it turns out, I could have easily inspected every single page of the Morgan’s Gutenberg Bible… on my neighbor’s iPad. In fact, on any computer connected to the internet. Their website features an incredible “Digital Facsimile” — a high-resolution color scan of each and every page, and the covers. With a spreading of the fingers, a reader can zoom in on the images and get much closer than he or she ever could at the museum. Every minor tear and smudge is available, worldwide. Isn’t this one more powerful step forward in the revolution that Gutenberg began 560 years ago?

And yet, isn’t there also something powerful about standing in the physical presence of the real book? The color scans are far more useful to anyone wishing to study the text itself — but the remarkable thing about this book is the thing itself. How it’s bound and what pains Gutenberg must have taken to make the type look handwritten. Was Gutenberg himself concerned that readers accustomed to the personal-touch would balk at lettering that appeared too machine-made? Perhaps the same concern can be seen today as eReader apps take care to simulate the effect of real pages being turned.

Being there with the Gutenberg Bible, I had revelations I would not have had looking at the digital facsimile. It’s the difference between studying the Grand Canyon on Google Earth, and standing on its rim.

However, I quickly realized that this bible was never meant to be sold to common readers. In addition to being written in Latin, it’s so huge that it could only be placed atop a lectern, where clerics could still guard it carefully. They could still choose which parts to read aloud and which to gloss over… even how to translate it into the parishioners’ language. Gutenberg’s revolution, in other words, may not have leaped, fully formed out of his egalitarian heart. Perhaps he just wanted to make a bigger and quicker buck, not so unlike Jeff Bezos or Steve Jobs today.

Will the inventions of these latter day Gutenbergs make the printed book as obsolete as his hand-copied one? Will everything someday just be a different format of electronic file? Or will eBooks — like radio, television, audiobooks, and even the paperback itself — simply become one further option for accessing humanity’s knowledge and stories?

Mark Twain wrote, “What the world is today, good and bad, it owes to Gutenberg. Everything can be traced to this source, but we are bound to bring him homage… for the bad that his colossal invention has brought about is overshadowed a thousand times by the good with which mankind has been favored.”

Standing in the presence of the Gutenberg Bible, I am glad that its pages can be studied electronically all around the globe, but also surer than ever that the digital is no replacement for the physical. Even though I can’t touch it, I can feel its weight. Knowing it is a privilege to see it, I pay more attention than I did to the digital copy, which I played with distractedly for a few moments before going to check my email, thinking that the facsimile will always be accessible later.

Leaving the Morgan Library, I felt better; more in touch with the things that I believe. These new technologies can bring books beyond their existing limits, and share knowledge with many who could not access it before. Yet for all they offer, they cannot fully replicate the authentic experience: it is difficult to treasure a digital file, to pass it on to a loved one, or to savor its impressive mass. Perhaps future upgrades will attempt to solve these shortcomings. Surely many readers will not mind the trade-offs. Surely others will come to appreciate printed words all the more, seeking a primacy and depth they’ve grown to miss.

On the subway ride home, I saw readers engrossed in their weightless Kindles, sitting alongside those whose heavy books were creased and filled with post-it notes. None of the riders seemed offended by the others; they were too busy reading to mind anyone else. It occurred to me that in 5,000 years, the act of reading has never meant only one thing to every reader. For centuries we’ve read to learn new things about the world at the exact same moment that we read to escape from it. The future cannot be so different.

***

— Kristopher Jansma is a writer and teacher living in Manhattan. His debut novel, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards will be published by Viking Press in 2013. He has studied The Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University and has an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University. He is a full-time Lecturer at Manhattanville College and also teaches at SUNY Purchase. Recently, his short story “A Summer Wedding” won 2nd prize in The Blue Mesa Review’s 2011 Fiction Contest, judged by writer Lori Ostlund. His essays and fiction can also be found on The Millions, ASweetLife.org, The 322 Review, Opium Magazine, The Columbia Spectator, and The (Somewhat) Complete Works of Kristopher Jansma. You can also find him on Facebook.

Photo via NYC Wanderer.