interviews

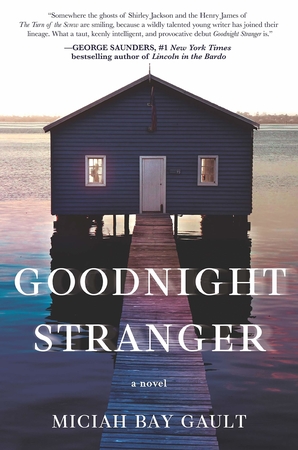

Loneliness Is a Ghost

Miciah Bay Gault, author of "Goodnight Stranger," on non-belonging and writing the supernatural

Do you ever have that feeling that you can trust a person you’ve never met before? You can’t quite explain this sensation to yourself, but this is a matter beyond language or rational thinking. Your whole body is somehow pulled to this alluring person, so much so that you would trust them with your love, and maybe even your life. How exhilarating and freeing it is to be totally immersed in that ungrounded attraction. However, be cautious as you are led into temptation, author Miciah Bay Gault reminds us: people are not always who you think they are.

In her novel, Goodnight Stranger, Gault weaves the tale of Lydia Moore, a young woman who lives with her pathologically shy twin brother, Lucas, on Wolf Island off the coast of Massachusetts. They are haunted daily by the loss of their baby brother, their triplet, and the mystery surrounding his death. When a handsome stranger arrives on the island, Lydia is instantly enamored with him, despite Lucas’s belief that this stranger is somehow the reincarnation of their dead brother. Gault’s gripping prose develops into a toe-curling blend of romance and literary suspense as Lydia discovers unsettling truths about the mysterious stranger, the ghostly inhabitants of Wolf Island, and her own family’s dark secrets.

I spoke to Miciah Bay Gault about longing, belonging, and other desires of the human heart.

Cameron Finch: I’ve heard you say that your writing career really took off after an essay of yours was published in Tin House a few years ago. Could you tell us briefly about that essay and the impact that its publication has had on your work since?

Miciah Bay Gault: Yes, that’s 100% true! The essay was about a student I encountered while teaching English Composition at the Community College of Vermont who’d spent two years in prison for grave-robbing. He was brilliant, and remarkably beautiful and engaging, and his story was just so strange and surprising. The essay told his story, and investigated other cultural and literary narratives about grave-robbing, focusing especially on skulls, and explored too my own obsession with this story, which I recognized as bizarre.

The essay was called “My Own Private Byron,” and its publication did lead to great things in my writing life. In my bio in Tin House, I mentioned that I was working on my first novel, and an agent who saw the essay contacted me to ask about it. I happened to be in labor when I got the email from the agent, Jenni Ferrari-Adler at Union Literary. Basically between contractions, I told my husband, “Do me a favor. Write her back, tell her I’m busy? But I’ll get back to her really soon.” I sent her the manuscript a few weeks later, and she replied within 24 hours, saying that the manuscript needed a lot of work, and she was willing if I was. Of course I was. I worked on the novel for the next four years with input from Jenni.

CF: A real labor of love, you might say (if you’re into puns)? The novel that emerged from that fateful email with Jenni was, of course, Goodnight Stranger! What was the seedling for this mysterious and sexy and deeply emotional tale?

MBG: First of all, thank you. I can’t imagine better praise than “mysterious and sexy and deeply emotional.” I read a New Yorker piece years ago about a couple’s struggle with infertility—which has nothing to do with Goodnight Stranger. The New Yorker essay ends with the birth of one daughter after years of heartache and lost pregnancies. I found myself wondering about the daughter—was she haunted all her life by the thought of those siblings she might have had? Was she lonely? Did she long to know them?

The first concrete image I saw from Goodnight Stranger was two grown-up siblings standing in a doorway looking across the threshold at a stranger. I imagined the air charged like the air before a storm, crackling with hope and fear and desire. And one of the siblings says, “It’s him.”

That’s all I had. I knew this was a story about siblings who had been haunted all their lives by a brother who’d died, and I knew a stranger would show up who was eerily familiar to them. At first I thought it might be a short story, but it ended up being too unruly and complicated for that.

CF: “Eerily familiar” is such a great way to describe how Lydia and Lucas feel toward “the stranger.” And yet, the siblings believe wildly different truths about the stranger’s past and present. So much of this novel hinges on people’s beliefs and intuitions about one another, which fascinates me. I’m reminded of Lydia’s mother, who believed that pieces of the soul could splinter off over time.

Beliefs are quite the concept to explore. As abstract as they may be, they certainly tell us a lot about a character based on the space they allow them to take up in their lives, the meaning they assign to those beliefs, and the identities they draw from them. How do your own beliefs, whether that’s your belief in other people or in another world beyond our own, influence your fiction?

MBG: To start, I’ll say that I’m not sure you can really know a person—or a character—without knowing what they believe. So thanks for noticing what a big role that plays in Goodnight Stranger.

I think a lot about obsessions, and I like to let my characters obsess. I also think it’s a good idea for writers to notice, and even cultivate, their own obsessions. I guess I should clarify: I don’t mean creepy obsessions with other people (okay for characters, not great for writers), and I also don’t mean the small, needling quotidian worries that occupy so much real estate in our minds. What I think is good for writers to cultivate is preoccupations, fears, desires—because somewhere in the chemistry between the people we are and the things we obsess about is a kind of beautiful energy that gets a little nearer what’s primal, or at least primary, in our natures.

So at the risk of sounding embarrassingly lofty, I believe we (writers) should chase our fears and delights, looking for what’s true about us. Am I answering the question? I might actually be dodging it.

I don’t have religious beliefs, so when you ask about beliefs, I think in terms of values. My third grader is doing this big project in school right now called “This is me and what I value.” The kids have to identify and present their values. It’s hard work for eight-year-olds, and it’s been forcing me to really articulate my own values in an effort to clarify for my kids exactly what values are. The best I can do when trying to explain things to my kids is that I believe in luck, kindness, and curiosity (the pursuit of obsessions). Those things sound so simple, but actually they’re giant concepts, and messy, and multi-faceted. I won’t delve into all the complexities here, but I will say that kindness, luck, and curiosity are the guiding principles of my writing practice, and my professional life.

CF: Goodnight Stranger is set on a fictional island called Wolf Island, off the coast of Massachusetts, where the majority of people who come and go each day are tourists. The residents of the island rarely travel far from their homes. You write this brilliant line: “I was an expert on tourists. They didn’t know me, but I knew them. Some … tried to capture the island, fit it onto a scrapbook page. Some came because they loved beauty. Some came to remember the past, or to refuse the future.” Lydia, the novel’s narrator, goes on to list three types of people: the tourist, the returning visitor, and the islander. As the author of Lydia’s world, which are you?

MBG: This question is making me laugh! I’ve always had a strong feeling that I don’t fit into any category, even though I (like Lydia) am inclined to categorize. Right now, for instance, I want to say that a lot of writers share this sense of not belonging in one category or another—but see how that creates another category (non-belonging)?

The first image I saw was two grown-up siblings standing in a doorway looking at a stranger.

When I was a kid, I really wanted to belong, of course. I moved around a lot: Vermont, Sanibel Island, Indiana, Sanibel Island again, southern Maryland, all before I was thirteen. We moved to Cape Cod the summer before high school started, and the place immediately felt like home to me—love at first sight. Even though I felt like I belonged in that place, I was acutely aware that I wasn’t really a local like so many of the other kids who had gone to kindergarten or preschool together. I also didn’t have the same aura the summer kids brought—of being from somewhere more urbane. The summer kids in my town weren’t tourists, not just visiting—they came every summer, and often their parents were oceanographers or marine biologists teaching or researching at one of the science institutes.

In Goodnight Stranger, Lydia identifies as an Islander, for sure, but she also so often feels like she’s an observer, not really part of the action. I think that’s how I felt growing up—still feel now—that I don’t belong in any categories, that I’m always just outside them. And of course I also know that categories aren’t permanent or even real; they’re just invisible filing systems, and they can shift and reorganize in an instant. They’re so comforting though, aren’t they? Lydia categorizes compulsively. I like the part where she’s drunkenly trying to categorize at the bar:

‘There are three types of people in this world,’ I told Eliot Moniz when he brought me one more Glenmorangie. ‘The ones who are dangerous. The ones who love the ones who are dangerous. And the ones who protect the ones who love the ones who are dangerous.’

I always think that’s really funny—that grasping for labels, when really she’s just describing the very specific situation she’s in with Cole and Lucas.

CF: In your Salon essay, “Let Us All Praise Loneliness,” you wisely state that both you and your characters need loneliness in order to grow and change. After many years of searching for “the opposite of loneliness” in Portland, the UK, and your college days at Syracuse, you now live with your family in Vermont, a state that is host to a number of haunted sites and stories. That ghostly imagery and regional folklore, such as the legend of Emily’s Bridge, features heavily in the plot of Goodnight Stranger. How do you see loneliness and the supernatural speaking to one another in your novel?

MBG: Oh yes, I definitely see a connection between loneliness and the supernatural in the novel, and I’m happy you asked about it. The way I see it: for Lydia and Lucas, their loneliness, the intensity of their longing for this lost brother, for family, for a sense of belonging, is what makes them both so receptive to the stranger, and to believing the unbelievable. Loneliness is like a ghost in the room with them.

CF: Were there any particular books/films/soundtracks you consumed while writing Goodnight Stranger?

MBG: The novel took fifteen years to finish, so there were a lot of books, films, and music during that time! But here’s what’s coming to mind: In the final stages of revision, I read Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle and Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, looking for ways to sustain suspense over hundreds of pages. During that time I also read The Hundred Year House by Rebecca Makkai and The Kept by James Scott, neither of which is a “suspense” book, and yet I flew through both of those novels, madly turning pages.

You have to ask and answer questions throughout the book. You can’t leave all the questions unanswered until the end.

Creating a mood came easy to me, as did building the world of Wolf Island. The characters came easy to me; I could hear their voices and had a clear sense of their essence. But what didn’t come easy was making a fast-paced plot. I wrestled with that for years. So I was paying attention to books that were fast-paced, that created a sense of urgency, that sense of rolling down a hill, that feeling of momentum. One thing I realized from reading those books was that posing questions is only the first step in creating that sense of urgency. Answering questions regularly is just as important. You have to ask and answer questions throughout the book; you can’t leave all the questions unanswered until the end. I feel like this is so elementary, and basically the way any episode of Scooby Doo is structured, so I’m not sure why it took me so long to learn. To be honest, I don’t think I’ve fully learned it yet. I’m still trying.

When I was writing the first draft of the book, I was in the MFA program at Syracuse, and I listened to a lot of Tom Waits, which is the music I always imagine playing in the bar on Wolf Island. Specifically, it was The Early Years, Volume Two. I have such a visceral memory of writing in my apartment on Westcott Street, probably wrapped up in a blanket, the snow coming down outside (it snowed every day of the winter), with that broody, Tom Waits carnival sound in the background.