essays

MEDIA FRANKENSTEIN: Ghostbusters

THE HEAD: The Vanishers by Heidi Julavits (2013)

This phrase from a friend once stuck in my mind describing how women are cruel to each other: “girl-on-girl violence.” It implies, on the one hand, that women can wound just as much if not more than the most violent men, and yet on another that they are above it, that cruelty reduces them to middle-school girlhood and that in a society that tells them to smile, what to do with their bodies, they owe it to each other to be basically decent — collegial, if they can stand it (the friend was female, by the way). Heidi Julavits’ 4th novel The Vanishers (2013)simultaneously attempts to decipher the rulebook of female cruelty and explode it by setting her own unique tale of “girl-on-girl violence” at the Institute of Integrated Parapsychology — aka the Workshop — a sort of Deep Springs for spiritual mediums in rural New Hampshire. Here Julia Severn, a psychic prodigy, falls afoul of house mother Madame Ackerman and, in the wake of a devastating psychic attack that makes Julia’s gums bleed, her fingernails snap, her scalp chafe and her bowels rebel, Julia flees to Manhattan. There Julia becomes embroiled in the search for a missing avant-garde filmmaker named Dominique Varga, which leads her on a madcap and frequently uncanny quest through dueling milieux of plastic surgery-enthusiasts, vanishing cults, schizophrenics and a Hungarian skin-care heiress. But where does the ghost enter in, you might ask? In the tragic exemplar of Julia’s mother, who Sylvia-Plath-ed herself into the ether when Julia was just a girl (the poet and her suicide become a motif throughout the novel) and appears to be somehow related to Varga. Our hero has meanwhile begun to receive a series of spectrally threatening emails — “a blob of clockwise-spinning fog, inside of which I could occasionally discern the shape of a woman lying motionless in a bed.” These ghost-in-the-machine missives are coming from someone called only “aconcernedfriend,” whom Julia at first assumes is Madame Ackerman — or someone privy, anyway, to the soul-crushing way that her mother checked out. (Where Plath used the oven, Julia’s swallowed pills). This haunting and dissociated mother/daughter relationship is what lies at the core of Julavits’ novel, which locates itself by and large among women. Radiating out like waves from the dark astral limbo that Julia visits in her psychic “regressions” are various other female pairings (mentor and protégé, friend and friend, a woman’s kinship with herself).

<em>The Vanishers </em>brilliantly subverts both the web-work detective novel and the metaphysical ghost story in having its veils of supernatural mystery fall away on nothing less than a mother’s troubled love for her daughter, and vice-versa.

In embracing ghost story tropes amidst a largely female milieu, the novel suggests a substratum of real, harmful chaos beneath the cat scratching and bless-your-heart manners American culture attributes to women, more smartly brought off for the signature fact that Julavits’ mediums are anything but passive as the 19th and 20th centuries have them (e.g. a woman is to spirits as a tampon is to blood), but actively nasty and unwisely fucked with. The ghost gets busted in the end, but never in the way you’d think.

THE TORSO: Portishead’s Portishead (1997)

What better record to underscore The Vanishers’ substratum of female chaos than the British band Portishead’s sophomore outing Portishead (1997). Widely classed in with the mid-to-late 90’s phenomenon of trip-hop alongside Tricky and Massive Attack, Portishead, fronted by vocalist Beth Gibbons, has also been described as “Gothic hip-hop” or “musique noire for a movie not yet made.” You need look no further than the album’s second track “All Mine” (also released as a single) for confirmation, in which a big-stepping, Dick Tracy-esque horn section with a mournful undercurrent of string instruments punctuated by shudders of deep bass is subsumed by a massively twanging ascension of guitar. Over the course of some very impressive (yet never straining) vocal spikes and declivities, Gibbons sings: “All the stars may shine bright/ All the clouds may be white/ But when you smile/ Ohh how I feel so good/ That I can hardly wait/ To hold you/ Enfold you/ Never enough/ Render your heart to me/ All mine…/ You have to be.” Sure, the lyrics could be and most likely are the musical equivalent of a magazine-cutout stalker’s paean to some former lover (if I can’t have you no one will); but even so they might, too, signal the fallout from a female friendship gone awry or a mother’s unbounded and terrible love. Gibbons has the voice of some malign songbird or a spirit in limbo, beseeching the living. A few of the songs on Portishead (most notably “Cowboys,” “Over” and “Elysium”) could go on to score Julia Severn’s astral projections in The Vanishers, in which she wanders the halls of a “bluestone” building “varicrosed by dead ivy” and encounters a spirit wolf named Fenrir,with eerie perfection. Portishead’s musical arrangements — a mixture of nightclub orchestra, beat-box minimalism and a record player repeating itself in the ballroom of a haunted mansion — are painfully crisp at first, even over-produced, only to succumb to guitar-swirling and record-scratching entropy as the tracks progress.

If there’s a ghost in <em>Portishead</em>, then it’s the ghost of thwarted love.

The album takes shape as an anguished attempt to reckon with the fact that even when love has died in the mind of the love object — or never lived there to begin with — it will never succumb in the mind of the lover. It struggles, haunted, hapless, on.

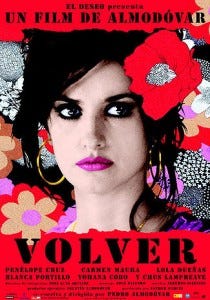

THE LEGS: Volver dir. Pedro Almodóvar (2006)

Where The Vanishers and Portishead envelope us in spectral fog, Pedro Almodóvar’s film Volver (2006) adopts a more concrete approach — say, a fog machine that breaks down and stutters every few minutes to reveal to us our beautiful and mundane surroundings. Although Volver also has undertones of noir and the supernatural (as do many of Almodóvar’s movies — see Bad Education (2004) and The Skin I Live In (2011), respectively) and although it, too, like The Vanishers is a clever subversion of the ghost story, Volver utilizes an almost completely female cast led by Penèlope Cruz and Lola Dueñas to tell the far more earthbound story of three generations of Spanish women. Switching back and forth between Madrid and the fictional wind-swept village of Alcanfor de la Infantas (translates: “Camphor of the Princesses”), the film follows Raimunda (Penèlope Cruz), her teenage daughter Paula (Yohana Cobo), Raimunda’s sister Sole (Lola Dueñas) and Sole and Raimunda’s mother Irene (Carmen Maura), who has died in a fire three years previous to when the movie begins but whose remarkably chatty and un-charred corpse begins to appear to various members of the family when they return to Alcanfor for the funeral of their beloved Tía Paula. Almodóvar is a phenomenally talented and poetic filmmaker. Several early scenes in the film are nothing short of astounding, including a high-angle shot at Aunt Paula’s wake that has dozens of black-clad biddies clutching at Sole while muttering their condolences which achieves an unlikely harmony between poignancy and claustrophobia. Speaking of those old Spanish women in mourning garb, they’re just the tip of the coffin when it comes to female presence in the film. All of the principals are women and damn fine actresses into the bargain, especially Cruz — Almodóvar, in many ways the anti-Hitchcock Hitchcock, clearly reveres women and has always managed to elicit career-making performances from them — and apart from a few ancillary characters or characters who are some iteration of absent or dead, there is hardly a man to be found in Volver. Indeed, the early murder and concealment of a particularly nasty male specimen comes to seem as inconsequential after a certain point as the character himself as the film draws focus more and more on the relationships among the women. Raimunda’s mother continues to haunt, hiding underneath beds, in car-trunks, in spare rooms. You begin to suspect that what she is is far more frightening than a ghost: a dispossessed person who suffers and loves and needs her daughters more than ever. It’s a curiously suspenseful and innovative use of magical realist tropes by Almodóvar — black comedy leavened by wrenching tenderness. And while Volver is gentler in its harnessing of female chaos than either The Vanishers or Portishead, its principle players don’t always play nice. In a kitchen scene between Raimunda and her estranged ghost-mother Irene, Irene asks: “Have you always had such a big chest?” to which Raimunda answers with pained incredulity: “Yes, since I was little.” Irene’s response: “I remembered you having less. Have you had anything done?” As Raimunda attempts to confront her own troubled past while shielding her already-far-from-innocent daughter from the world’s utmost cruelties, family secrets emerge, alliances are made, broken and repaired among the sisters and the Márquezian winds of Alcanfor de las Infantas continue to blow. When Paula’s ghost gets exorcised, it’s a quiet and world-weary moment for all, suggesting at last that the stygian realm underlying the bedrock of female relations isn’t chaotic so much as just grasping.

What the supernaturalism of <em>The Vanishers, Portishead </em>and <em>Volver </em>seem to be saying is that when women (and by extension all humans) treat each other badly or underhandedly there is always something far more rarified and mysterious at work: people trying, clumsily, to bare to each other their unquiet souls.

Alternative Cuts:

(Big Machine by Victor LaValle (2009); Tricky’s Maxinquay (1995); Dark City dir. Alex Proyas (1998))

(The Innkeepers dir. Ti West (2011); Ghost B.C.’s Opus Eponymous (2010); The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson (1959))

(Beloved by Toni Morrison (1987); The Best of Billie Holiday: 20th Century Masters (2002); Kara Walker’s Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994)) (Ju-On dir. Takashi Shimizu (2002); Revenge: Eleven Dark Tales by Yoko Ogawa (2013); Boris’ Amplifier Worship (1998))

In Two Weeks: Surveillance

Two weeks ago: Manmade Apocalypse