interviews

Morgan Parker Thinks Black Women Are More than Just Magic

Candace Williams talks to the poet about “Magical Negro” and how meaning well isn’t enough in the era of the “Matt”

The first time I realized black woman poets exist in the present tense was in a packed audience at Bluestockings Bookstore listening to Morgan Parker read “99 Problems” in the fall of 2014. I had been exposed to very few poets during my K-12, undergraduate, and graduate studies. Out of the few poets I read in class, one of them was black. All of the poets were dead. Morgan Parker is a black woman and alive and is writing poems that exude the full range of emotion and experience — from joy, triumph, and humor, to horror, regret, and grief. The complex worlds inside myself, my grandmother, my mother, and my sister are rendered visible when Morgan reads her poems. Her latest book of poems, Magical Negro, is a running archive that documents, honors, complicates, and interrogates black womanhood.

Morgan Parker is the author of the poetry collections There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé, Other People’s Comfort Keeps Me Up At Night, and Magical Negro. Her debut young adult novel Who Put This Song On? is forthcoming in late 2019 and her debut book of nonfiction will be released in 2020. She is the recipient of a 2017 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship, winner of a 2016 Pushcart Prize, and a Cave Canem graduate fellow.

I was beyond excited to talk to Morgan Parker about blackness, magic, social media, and how “Matt” is doing these days.

Candace Williams: You’ve been away but I still see you as a New York poet. I am thinking of your poem “Magical Negro #80: Brooklyn”. Do you still consider yourself to be a New York or Brooklyn poet?

Morgan Parker: I spent all of my adult years until now in New York so it really kind of got under my skin. So, it’s still very much in the way that I think about poems and I love Brooklyn, like I love it. I still believe there’s no other place like it. There isn’t a neighborhood to match it anywhere.

Something I struggle with in my work is wanting to represent collective but not the collective. I can’t represent everybody.

I felt very connected to the folks in my neighborhood and was certainly a person who liked to stay in my neighborhood and talk to my neighbors and sit out on the porch, go to the block parties and all that stuff. I was able to pay more for my rent than if I had lived there my whole life. Then, I was coming to it from, you know, a different state altogether, and then an Ivy League school. You know what I mean? I had the feeling with my own status as a gentrifier.

Something I struggle with in my work is wanting to represent collective but not the collective. You know. I can’t represent everybody. We’re writing our own kind of history and document. I would hate for this era to be only documented by articles about millennials and shit like that. This is something I’ve been thinking about lately, I never thought I would say something like this, but even like the kind of journalistic and some of I think the best thinkers of our time, but if they’re tied to a particular media outlet I feel that things are being skewed a little bit. And that’s where art comes in right?

I really have a feeling that some of our homies that are working in these places have to kind of compromise a little bit. I know that’s how journalism works right now and so I think it’s important for artists to fill in the blanks. I’m not in a corporate position so I can do that. It’s becoming increasingly important for us to document ourselves.

I think this idea of representation has slowed us down a little bit. We’re reflected in these major ways but it’s still never enough. It’s still never specific enough. It’s still not always exactly in our words.

CW: It would also be totally absurd if we didn’t talk about magical negroes and the title of your book. The concept of a Magical Negro is when a white production team creates this magical stock character who is black. That black character is there to interact with white people in a certain way and teach a white audience something.

I think the beauty of this book is that you’ve turned that concept on its head in some ways and you’ve reframed it in ways that are pretty complicated. I’d love to hear your thoughts about magic, the Magical Negro, and how magic operates within blackness in this collection, and in your work in general.

MP: I think I have a way more complicated relationship with it. That’s one reason I like your book. You’re coming at magic from this totally candid very nerdy scientific way and I feel like it is a different view than just saying “black women are magic.” You know what I mean? I always like a little nuance and little bit more rigor. I was in the Black Girl Magic Anthology and support it but I also think that there’s more. We can’t just say, “Oh yeah, these people are magic.” And I think there’s a danger to that, obviously, when we have someone like Michael Brown turned into this devil with superhuman strength. That is the negative connotation of magic.

I do feel that we have, that we wield a particular magic that’s the only way we could have gotten out of where we’ve been and still be standing. You know? That is just what it is. It’s insane what we go through and what we internalize and what we carry. There’s no way we could do so without a kind of magic that is strength, that is ancestral, and that is rooted in history and legacy.

I do feel that we wield a particular magic that’s the only way we could have gotten out of where we’ve been and still be standing.

I also think that it’s often an excuse to see a magical being and not a person. I can’t tell you how many times, I’m still trying to write over and over this, that feeling of not being a person. Knowing that you know, white people are looking at you and not seeing the whole of your humanity. Just seeing you know, almost this kind of mirage of reflections from their own mind.

I think it’s way more complicated than we allow ourselves to think about. Yeah, I think that’s something I wanted to explore. The idea of who I think is magic, who they think is magic, and for what reasons and all of that.

CW: You just used the term “writing over” and I wrote that down because I read another interview that you felt frustrated about “reading over.” When I read your writing, I think you’re talking very clearly about black people. I think you were saying that when you write you are frustrated because you’re writing, and other people are writing, but white people just aren’t hearing it, and they’re not seeing it.

That’s a big struggle. I remember I had a sestina published that is clearly about black trauma at the hands of scientific and medical racism. Multiple white women messaged me and were like, “Oh, I like how you’re writing about the medical industrial complex…women are given all these pills,” and I remember thinking that all of that is true but my poem is about black people too. If we let people who aren’t black use tag lines like “Oh, well, #blackgirlmagic,” it actually misses the point.

MP: Yes. It’s like, get to the black woman. Can I have some space?

CW: In order for them to listen to us, they actually have to let us speak. Not give us money but the wealth to create our own institutions and media outlets and pathways. I feel like sometimes people latch on to these taglines and these very basic ideas, and it actually makes people unable to read what we’re actually saying. So they’re just going to read the parts that are easy, and be like, “Oh, yeah, I’m against medical racism, and I’m sad about Mike Brown.” Yeah, but I’m just like, “Did you also realize I write about white women and white men, and what happens to me in these social interactions? That’s something you should also be taking away from this,” but I feel like they’re just reading over it, and that is very frustrating.

MP: It really is. I’m very afraid to release this book and it’s because I put so much into it, to the point where afterwards I was like, “I maybe went a little too far.” I hurt myself in doing it. Not because I think I said too much but just because it was extremely challenging and emotional for me. I can’t stand the idea that I will have done that and still be read over. That’s that fear. With Beyoncé, I definitely felt like I wanted to make something that was incredibly impactful for my people, but also that a lot of other people would feel they could read, and then maybe somehow be brought in that way, through the black culture.

There is black culture in here. I wrote it. I felt I was less focused on a wide audience, and making white people comfortable in it, I guess. I did that on purpose, because it’s just like … All right, I said all this stuff, and you … Like I wrote a poem that says, “What if I said, ‘I’m tired,’ and they heard me wrong, said, ‘Sing it.’” Literally, people, when I say, “God, I really just don’t want to be alive today,” people are like, “Same.” I’m like, “You don’t understand!” Like what in the fuck? “What more can I say to you?”

Like, can I live, or what? That’s the thing. There’s something in this particular era of people tweeting things out, and performing grief, and performing theater, that it all feels fake. It all feels ephemeral. It’s scary for me, because I do want to believe that literature and art can be effective in the real world, but it won’t if we’re only seeing this art that’s made in the world for the world, and not by a person who’s suffering.

I think of the ease with which we forget that art is a thing made by people. It’s not just processed and delivered like a politician’s statement. This is coming from an emotional place, and I think it’s easy for us to retweet and not sit with something and say, “This is a major problem. How can I look in my life, in the world, when I go outside, away from my computer, and make sure that I’m not making someone feel this way?” But no one does that.

CW: No, they really don’t.

There’s something in this era of people tweeting, and performing grief, and performing theater, that it all feels fake.

MP: It’s to the point where I’ll go and do a reading and it’s only white women at the venue for the most part. Meanwhile, on my way over, a white girl bumps into me, and is like, “Oh, sorry. I didn’t see you.” That’s just like … I can’t … I don’t know. I don’t even know. I don’t know what to say. Actually, I was at a thrift store with my mom recently and there were really loud white girls pushing past us, and one of the white girls bumped into me, and was just like, “Oh, sorry. I didn’t see you.” And I looked, and she had an Audre Lorde tote bag. I was just like, “What is happening?” I was like, “Mom, see? See? That’s my book.”

I just don’t even…There’s no words. There’s no words. You can’t even write it. That dissonance is really scary to me.

CW: It seems like of the precursors, one of the drivers of our current situation, is the amount of dissonance that we let people live with, for different reasons. We don’t “let them live with it.” We have to or else we don’t survive. If I go to work, and I start pointing out dissonance (and I usually do), I’ll probably get in trouble, right? If you say, “Why did you say that? How come these rules say this, but then I do this, and I get in trouble? How come that person is doing this?” When you start to hold people accountable for dissonance, you’re on your way out. You don’t make it to year two in that job.

MP: We get so stuck in, especially these days, on what is true and what is false, what someone said, and what the actual words were, and blah, blah, blah. There is no conception of what those words do, and what those actions do, in terms of emotions. So it’s like, “Okay, maybe you didn’t mean it in this way. So what? I acknowledge that you didn’t mean it that way, but what I’m telling you is when you said this, I felt this.” I think that we’re getting really far away from that. There’s a kind of ego that people are not willing to let go.

I’m going to take this space in this book that I’m writing to force you into my perspective.

If you could just say, “Yeah, damn. I understand what you’re saying. That was shitty. I definitely didn’t mean it that way, but now I know,” instead of holding your party line, and saying, “Well, I didn’t mean it, so there’s no reason you should be upset.” That’s absurd, but I feel like that’s a little bit where we are. So I guess that’s why I feel so compelled to just witness and be very raw about, “This is what I feel, and this is what has happened to me.” Actually, I’m going to take this space in this book that I’m writing to force you into my perspective.

CW: Yeah, definitely. That feeling of just being out in the world and dealing with institutions that are not made for me. I don’t think people realize how much navigation it takes just to survive, to even think my thoughts are real, because people gaslight. For example, if I were to tell, most white people I know, that on a daily basis, I’m bumped into because people don’t see me, their first response would be, “Oh, well, that happens to me. That’s just a NYC thing. That’s not race.”

MP: Yeah. Then, even if they see it, they think it’s the first time it ever happened, because it’s the first time they’re seeing it. They still just say everything’s a one-off. But what, are we going to go running to them every single time it happens? No.

Also, why can’t you even take our word for it? You don’t have to see a YouTube clip of it happening over and over, in order to understand what we’re saying. That’s not humanity. That’s not humanity. That’s not fellowship and that’s not caring for another human being.

CW: You’re definitely one of my favorite people on Twitter. Is it still doing a lot for you? Does it still impact your world a lot? I mean, you’ve talked about how people kind of just read over your pain, and even use social media to kind of disassociate with it in a strange way.

MP: Oh, totally. Everyone thinks it’s like a Twitter personality. I’m like, “No, you guys. I just tweeted this because I couldn’t decide who to text it to.” Straight up, it’s not a persona. The expectation of an artist is to have this split public and private personality. Obviously, I’m a real person in real life. When I’m tweeting, I’m not just saying “I’m depressed” just to say it. I just am. I think it’s easy for people to say, “Amen.” and retweet but not call me. It’s weird. I like Twitter just because I like making jokes. I like the short commentary. I like having a documentation of everyday-ness mixed with political stuff. I like seeing the news in that way, rather than in a New York Times notification.

The expectation of an artist is to have this split public and private personality. Obviously, I’m a real person in real life.

I like seeing my friends’ views on things in a collected way but I don’t like the pressure. The pressure to say something, or to yell about something, and participate in this collective panic. That doesn’t work for me because I don’t feel safe doing that. Some people can do it. I can’t. I live alone. When everyone goes offline, I’m still just there panicking. I have to take care of myself in a lot of ways. Certain days, I’m not on Twitter. Certain days I’m on but I won’t comment. I can’t read every article and I think that part of it. The fact that you have to know every single thing that’s happening before you go on there. That’s the part I can’t hang with anymore.

I do like the collective tapestry of feelings in a moment. Mine are usually just like, “I’m very tired.” That’s what it is. But I think I’m very attracted to allowing for the mundane to enter the philosophical, and vice versa. That’s just how I talk and how I live. So that’s one thing that I do like about Twitter. Those two things can exist in the same space. That’s a comfort zone for me.

CW: I’m also thinking about your humor. I’m thinking about the poem “Preface to a Twenty Volume Joke Book.” I feel like I see humor in your poetry and that you’re humorous when I see you in-person. I was talking to Michelle Tea awhile ago, and she and I talked about queer humor, and how it’s incredibly important to queer culture and survival. How does humor fit into your work? How does it relate to blackness and black culture for you?

MP: Well, it’s about pain, right? That’s the blackest thing ever. To make a joke about something that is so incredibly painful. I really identify with comedians in that way. I feel like a lot of questions about what I’m up to would just be so much easier if I just called myself a comedian. I do what comedians do all the time. When I stand up on a stage, I’m talking about something unfortunate that happened to me, and it’s kind of funny, and it makes me think. I think that’s basically it.

Someone was like, “Have you ever thought of doing standup?” And I was like, “I haven’t been doing that?” That’s what it feels like. There are poems in between, but you know … some days, there aren’t that many poems that I read, and most of the time is just ringing my bells. I think that is something that … Performance is really empowering in that way, and I think that’s why comedians have the ability to stand in front of a group of white people, and make fun of them, really. That’s something that I do, and there is a coping in that, and just the performance of it.

All the kind of echoes in just that situation, of a black person standing in front of a group of white people, and being entertainment. The kind of … It’s all very complicated, and humor is always talked about in this healing way. I think it’s kind of true, but often what happens when an audience and a performer are involved, is that it’s kind of like who’s healing who? I think that thinking about that, and how a joke works, has really shaped the way that I write poems. It always has.

When I first started writing poems, it really was for the jokes. I was like, “Poems are dumb, and I don’t like poetry, and it’s all boring. But what a funny way to pick on …” I honestly started writing poems, and I was like, “I’m just going to write this poem about my college roommate,” who I didn’t like, and I just wrote some funny jabs, and would read that at parties. I still crack up that that was how I started. Finding a creative way to air a grievance, and a funny way of doing that. Poetry kind of fit that box for me.

It’s something that I carry with me, even when I’m writing about some of the hardest shit. And partly, they’re for me. If I’m not sitting and kind of chuckling at what I’ve said, then what the fuck are we doing? Then I’m just pulling it apart for no reason.

CW: That’s why I was so happy to see “Matt” in this book. I think “Matt” is one of my favorite poems of all time. Wendy Xu introduced it to me during a poetry workshop, and I read it on the subway, and was just blown away. I just feel like it just starts off as this roast of white men and how they behave toward black women, and then it just gets so deep so quickly. I remember reading it and laughing, and then I got emotional. I cried.

It’s been a while since you’ve written “Matt.” Has your relationship to that poem changed?

MP: My God. It is such its own thing, at this point. It’s just got its own little following. Even a few months after I’d written it, I was at a reading. I hadn’t even read that poem, I don’t think. I was just standing outside having a cigarette between sets, and some guy comes up to me and was like, “I just want to say I like your poems.” “Okay, whatever.” I’m walking away. I was like, “Hey, you can introduce yourself. I’m Morgan.” He was like, “Oh, my name’s Matt.” I was like, “Ha! I have a poem for you.” He was like, “That’s you?” He was like, “Fuck that poem. My ex sent it to me,” and I just started cracking up.

To make a joke about something that is so incredibly painful. That’s the blackest thing ever.

But I hear that a lot now. Women come up to me, and they’re like, “Listen. I sent this to all my people,” and there was one time a black girl came up to me, and she was like, “I have a Matt. I’m here with him.” Then she came back later, and was like, “This is my Matt. It’s a white guy.” He was like, “I’m Matt.” It’s like, this is amazing.

The poem interacts with audiences and changes depending on the audience. It really does have its own life now. I feel very happy when women come up to me, and are like, “I’ve emailed this to like five people.” That’s dope. That’s what poems should be doing. Straight up, my therapist was like, “I’m going to give this to a client.”

CW: Wow. That’s wild.

MP: I know, and it’s interesting, right, because it seems like such a simple poem. In some ways, it is. When I wrote that poem, I wrote it, and I never do this, I wrote it in maybe one draft. That was maybe the first time I’ve ever done that. But I think it was because I was living with it for so long. And it was something that I didn’t want to get wrong. So when I did write it, I woke up at 2 a.m. and started typing.

I think a poem like that is really hard to do because of the pulling in and because of the going deep part. You don’t want it to come too fast. It’s a very tough thing. What I wanted to talk about, was that feeling that happens. I could be in love with this person, but if it’s a white man, I will always have a split second flash of slave and slave master. Even if that’s not present in the dynamics of the relationship itself, that is always going to be flickering in the back of my mind and not in a negative way.

I remember trying to tell this to a white man and he just didn’t understand. I wanted to make space for that. I wanted to be poking fun at Matt, but also tender. I wanted the speaker to have this complicated relationship, but insist at the end that like, no, this is not, we’re not the first people. Morgan and Matt are not the first, this is not the first situation. You are a type, and I am a type to you. It goes back infinitely in history. We know white people have trouble with being a type. They can’t stand it.

Even these guys who are like, “that’s obviously me.” I’ve known so many guys in my life. It had to be exact. It had to be Vonnegut. I think there is a pleasure in saying “No, no, no. We see you exactly. We see you exactly. You’re so easy for me to pin down.” It makes them embarrassed. But, I think it makes them interrogate themselves in a way that no one else will force them to do. I think of Matt as the type of guy that gets a lot of passes, because he’s just so confused and he means well and blah, blah, blah. But, if we’re gonna have a revolution, we can’t have people who are just kind of passing into the next grade with no interrogation of themselves.

CW: Right. The problem is that dissonance we were talking about earlier. So just thinking of a lot of Bernie Sanders supporters and the things they were telling me. I’m pretty socialist myself, and they would just kind of assume that they were educating me about politics. And then I would go deeper, and I would be like, this is deeper than even policy stuff. This is about you and how you see the world and how you operate. And it’s just so limited, because it’s limited for all of us, yet your perspective has so much power over mine. And you think you’re right. And we’re going to give you a pass no matter what, because you hold the keys. You have the right family. You have the right degree.

MP: And, out of all the white guys, you’re nice. It’s easy to write an anti-Jeff Sessions essay but Matt never hurt anyone. I think it’s true to an extent but that doesn’t mean that the rock goes unturned. I think the same thing about a Rachel or a Becky. The “meaning well” is not enough in a time like this. Actually, I prefer to write these poems where these people, the Matts, will listen. They really do. They’re like, “Oh shit. Is that me? Damn.” I’m wearing a flannel right now. I see myself in this person. I see that. Reading at colleges is really excellent because I can see the guys kind of thinking, “Oh shit. Am I just like this? Is that all I am?” They’re interrogating their behavior. The women are kind of looking around like, “oh shit.”

I always read at colleges because this is the era of the Matt. These women need to know. And men need to know to be better.

I always read at colleges because this is the era of the Matt. These women need to know. White and black alike, beware. And men need to know to be better. Think more about who you’re being and the kind of attention that you’re paying to the world around you. College is a very important time to be doing that. College is where the Matts are fertilized in a way. I think that we can point that out while they still think it’s harmless. That’s really important. We actually do need allies but only if they’ll really listen to the way that we see the world. I think that happens, and like you’re saying, the problem is when everyone thinks we’re all seeing the same world. That’s ridiculous. And our perspective of the world is the last to be heard, obviously.

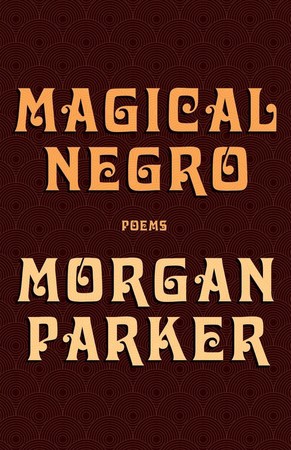

CW: I want to talk for a moment just about the physical object of the book. The first time I got it in the mail and held it, it felt like like when you go to a record store and you pick up this vinyl and you know this is going to as black as hell and awesome. You just know that you’re going to take this home and listen to it, it’s going to be awesome and black as fuck and great, right? That’s kind of how I felt when I first saw the book cover, and when I hold the book. The understated pattern in the background, the colors, the fonts. I would love to hear you talk a bit about the book as a physical object.

MP: Yeah, I’m notoriously involved in cover and design.

CW: Oh wow, I didn’t know that.

MP: Not every writer cares and not every writer really knows how to do that stuff. It’s not that I don’t trust others. I love collaborating with designers. This is my second time working with this designer. He read the book at the same time the editors were reading it. Early on, he had thoughts about colors, title treatments, and fonts. I told him my aesthetic and and let him go for it. I sent him the font.

We don’t have room right now to be afraid in the art that we’re making.

I love it. It feels very black. It has the right colors. I wanted it to some little patterns happening but not be too busy. For whatever reason, I didn’t want an image. I just wanted to think about the words “Magical Negro.” Those words felt like enough for this cover. It’s such a wild book where I feel like even the table of contents matters. I feel that about the vinyl. I recently bought an Isaac Hayes vinyl just because I like the cover. I looked at the song titles on the back and thought “I must have it.” I think about those sorts of things. Preparing the reader for an experience.

CW: I was just thinking about your work as an editor. You’ve worked in different modes of publishing. I was just wondering, let’s say that tomorrow you got this 20 million dollar grant to start a new publishing house in L.A., N.Y.C. or both. How would you approach that and what would your publishing and editing practice be? How might your institution be different than what we typically see in our current system of things?

MP: I would want to make a space for the writing and the publishing. I think the problem with publishing is that it thinks about only that aspect of making a book, and making a book is painstaking. It’s long. There’s a lot of thinking that goes into it before the marketing folks come in. I enjoy working with other writers. I’m not employed as an editor right now, but last week a friend came over to hand out candy to trick-or-treaters, and I was like, “Well, time to reorder your poetry book, come here. I don’t care. We’re doing this right now.” I aggressively laid out all the poems on the ground. That’s my joy. That’s fun for me. I think that’s what I miss about editing. Yes, there is such pleasure and satisfaction of putting a book in the world, and seeing it in bookstores. I miss the nitty-gritty of working with a writer and thinking about what the book is doing and what the writer wants the book to do. And how to help them do that. So, I guess if I were opening my own publishing business, which I love how you’re saying what if, but like I’m definitely going to do this.

My life is going to be long. I would be interested in working with writers from the very beginning—when they don’t have even the book yet. Or maybe they have some poems. And just like being involved in their kind of journey toward publication. I would also like to see a lot more archiving done and a lot more physical objects being made and a lot more artists working with artists.

We don’t have room right now to mess up because publishing is in this kind of capitalist space. I sympathize with that. I sympathize with the editors and the non-profit folks who are really struggling and for them to get the money for even those grants. They have to write these grants for poetry or painting or whatever. I think it’s intimidating for people. It’s scary to look into new ways of working. But, shouldn’t art be that? I think we don’t have room right now to be afraid in the art that we’re making.