Books & Culture

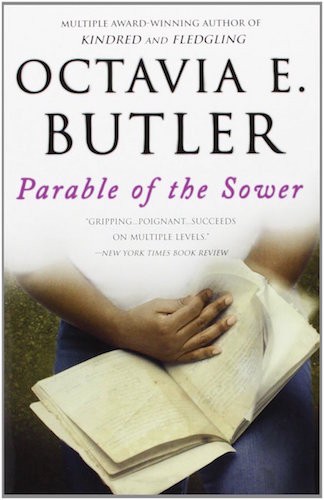

Now More than Ever, We Wish We Had These Lost Octavia Butler Novels

‘Unfinished Business’ examines the groundbreaking sci-fi writer’s plans for her ‘Earthseed’ series

Each month “Unfinished Business” will examine an unfinished work left behind by one of our greatest authors. What might have been genius, and what might have been better left locked in the drawer? How and why do we read these final words from our favorite writers — and what would they have to say about it? We’ll piece together the rumors and fragments and notes to find the real story.

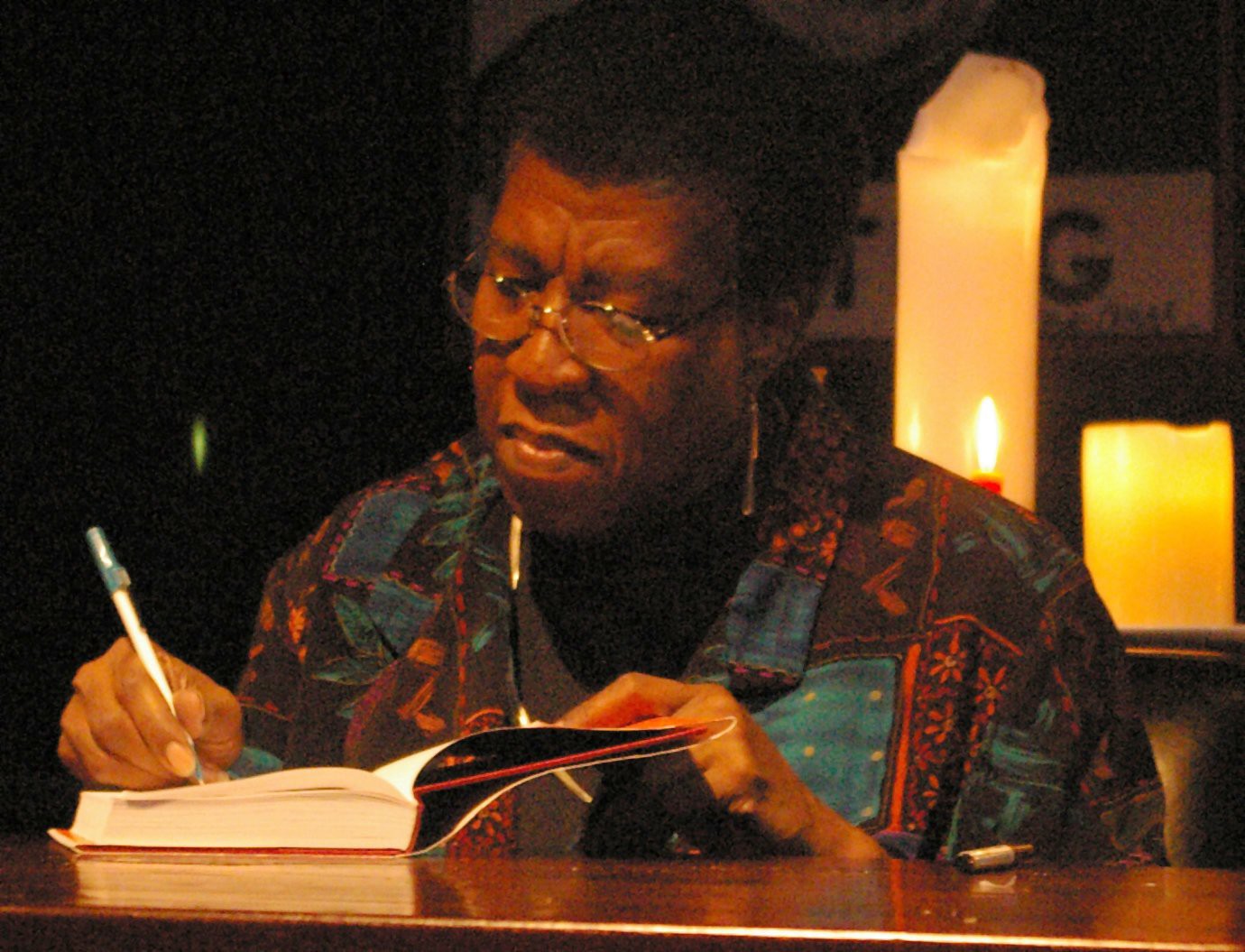

In 1989, Octavia Butler set out to write The Parable of the Sower, the first in a planned trilogy of novels about humanity’s uncertain future. Her many earlier novels had already established her as a titan of science fiction. She’d written awesomely weird books about telepaths and time travel and aliens and psionic vampires. Butler was an anomaly in the sci-fi world; in interviews, she often described herself by saying, “I’m black, I’m solitary, I’ve always been an outsider.” She had already upended a genre that had long been both very male and very white. But she wanted to do something even bigger.

In a lecture at MIT titled “‘The Devil Girl From Mars’: Why I Write Science Fiction,” Butler recalled reading that Robert Heinlein had once delineated three kinds of science fiction stories: “The what-if category; the if-only category; and the if-this-goes-on category.”

She had mastered the first two categories, and was intrigued by the third. The Parable of the Sower would be a starkly realist novel about where American might carry itself in a few short decades — if this goes on.

To do this, she amalgamated her own memories of growing up in the racially integrated Pasadena of the 1950s with contemporaneous news reports about rises in global warming, racism, violence, prison populations, and mega-corporations. In this way, she created the shattered America described by Lauren Oya Olamina, a black fifteen-year-old with “hyperempathy” living in a walled-up town outside of LA in 2024.

Told through Lauren’s diaries, the novel envisions the crises facing America thirty-some years later with eerie accuracy. Clean water is getting scarcer. Whole towns are being privatized by individual companies. Literacy is deteriorating—and, oh yeah, there’s a charismatic President promising to make the country great again.

As Gloria Steinem wrote last year in an essay celebrating the novel’s 25th anniversary, “If there is one thing scarier than a dystopian novel about the future, it’s one written in the past that has already begun to come true.”

The Parable of the Sower was published in 1993 and became a New York Times Notable Book the following year. Already a Hugo and Nebula award-winning writer, Butler soon became the first science fiction writer to ever receive the MacArthur Foundation “Genius Grant.” She said she hoped the prize, which at the time was $295,000, would help her to complete her work on the trilogy.

A year later she published a sequel, The Parable of the Talents, in which a religion based on Lauren’s diaries, called “Earthseed,” struggles against Christian fundamentalism.

At the time, Butler spoke in interviews about her ideas for the third book, The Parable of the Trickster, in which adherents of Earthseed would attempt to build a new society on another planet.

Butler spoke in interviews about her ideas for the third book, The Parable of the Trickster, in which adherents of Earthseed would attempt to build a new society on another planet.

But, struggling for years with depression and writer’s block, Butler would not finish the trilogy as she planned, though she would complete several new stories and a novel, Fledgling, about a race of vampires trying to co-exist with humans.

In 2006, Butler died of a stroke outside her home in Lake Forest Park, Washington. Her many papers now reside at the Huntington, a private library in San Marino, California. Curator Natalie Russell describes the collection as including “8,000 manuscripts, letters and photographs and an additional 80 boxes of ephemera.”

On display there now are numerous treasures, including working manuscript pages from The Parable of the Sower covered in her brightly colored notes: “More Sharing; More Sickness; More Death; More Racism; More Hispanics; More High Tech.”

There are the beautiful, bold affirmations that recently went viral online, which she wrote to frame her motives for writing: “Tell Stories Filled With Facts. Make People Touch and Taste and KNOW. Make People FEEL! FEEL! FEEL!” On one page of her journals she visualized the success that she desired: “I am a Bestselling Writer. I write Bestselling Books And Excellent Short Stories. Both Books and Short Stories win prizes and awards.”

Read Octavia E. Butler’s Inspiring Message to Herself

But what is not on public view are the drafts — the things she had hoped to write someday and never did, including The Parable of the Trickster.

Scholar Gerry Canavan described getting a look at that work-in-progress for the LA Review of Books in 2014:

Last December I had the improbable privilege to be the very first scholar to open the boxes at the Huntington that contain what Butler had written of Trickster before her death. What I found were dozens upon dozens of false starts for the novel, some petering out after twenty or thirty pages, others after just two or three; this cycle of narrative failure is recorded over hundreds of pages of discarded drafts. Frustrated by writer’s block, frustrated by blood pressure medication that she felt inhibited her creativity and vitality, and frustrated by the sense that she had no story for Trickster, only a “situation,” Butler started and stopped the novel over and over again from 1989 until her death, never getting far from the beginning.

The novel’s many abandoned openings revolve around another woman, Imara, living on an Earthseed colony in the future on a planet called “Bow,” far from Earth. It is not the heaven that was hoped for, but “gray, dank, and utterly miserable.” The people of Bow cannot return to Earth and are immeasurably homesick. Butler wrote in a note, “Think of our homesickness as a phantom-limb pain — a somehow neurologically incomplete amputation. Think of problems with the new world as graft-versus-host disease — a mutual attempt at rejection.”

From there Butler became hopelessly blocked — though not exactly in the commonly-held image of writers’ block, of staring day after day at a blank page, lacking inspiration and confidence. In fact, as Canavan describes, her “dozens upon dozens” of drafts represent a wide range of ambitious ideas.

In some versions, the colonists struggle with a creeping blindness. In others, they develop a terrible telepathy. There are versions where Imara must solve a murder and versions where Imara herself is murdered but becomes a ghost. “Sometimes Imara is an Earthseed skeptic; other times she is a true believer; sometimes she is, like Olamina, a hyperempath; still other times the cure for ‘sharing’ has been discovered in the form of an easy, noninvasive pill,” writes Canavan. “Sometimes Bow is inhabited by small animals, other times by dinosaur-like giant sauropods, and still other times by just moss and lichens; sometimes the colonists seem to encounter intelligent aliens who might be real, but might just be tokens of their escalating collective madness; and on and on and on.”

In some versions of The Parable of the Trickster, the colonists struggle with a creeping blindness. In others, they develop a terrible telepathy.

Canavan reveals that Butler hoped to for this book to serve not as the last in a trilogy, but as the middle of a seven-part series. (Take note, George R.R. Martin!) Trickster was to be the first of four new novels about life on Bow and the colonists’ struggle to build a better humanity. He writes that the colonists “can choose: either live together, work together, struggle together, and pray together, or else hoard food alone, scheme alone, lose their minds alone, breakdown and die and murder each other alone.”

Four more books. That would be how long it would take, in Butler’s estimation, for the human beings of the future to move past their homesickness, their biology, and their history and truly become capable of working towards a common decency. She saw hope, but only a long way off.

In 2001, during a speech to the U.N.’s World Conference Against Racism, Butler explained that before embarking on the first Parable novel she had instead dreamed about writing a novel about a utopian civilization where everyone possessed a kind of hyperempathy. For a time she thought that, at least in fiction, she could create a world where “people were inclined either to accept one another’s differences or at least to behave as though they accepted them since any act of resentment they commit would be punished immediately, personally, inevitably.”

But soon she realized this would never work. “Popular, painful sports like boxing and football convinced me that the threat of shared pain wouldn’t necessarily make people behave better toward one another,” she said. “And it might cause trouble. For instance, it might stop people from entering the health care professions. Nursing would become very unpopular. And who would want to be a dentist in such a society? So much for fiction.”

Instead she created Lauren, a lone hyperempathic girl in a society of the empathy-deficient. Empathy was, she realized, not the solution but an affliction.

Support Electric Lit: Become a Member!

So much for fiction? I don’t know about that. Butler may have ended up writing a dystopia instead of a utopia, but what she wrote gets right to the heart of our crises. It was not, she said, intended to be a prophecy, but rather a cautionary tale.

Butler may have ended up writing a dystopia instead of a utopia, but what she wrote gets right to the heart of our crises.

The rest of her speech to the U.N. that day is an exact outline for what she wanted the rest of the Parable books to be about — a way out that she did not live to write herself. Fortunately, what she did leave us influenced a generation of writers from every margin in society to continue her work.

“Whatever is the source of our intolerance, what can we do about it?” Butler asked. “Of course, we can resist acting on our nastier hierarchical tendencies. Most of us do that most of the time already. […] Will this work? Well, it hasn’t so far. Too many people will not, perhaps cannot, do it. There is, unfortunately, satisfaction to be enjoyed in feeling superior to other people.”

She lists the basic human traits that catalyze our nasty tendencies into nasty behavior: ignorance, fear, disease, hunger, suspicion, hatred, war, greed, and vengeance.

“Amid all this, does tolerance have a chance? Only if we want it to. Only when we want it to. Tolerance, like any aspect of peace, is forever a work in progress, never completed, and, if we’re as intelligent as we like to think we are, never abandoned.”