Lit Mags

If On a Country Road a Car Crash

"The Frozen Finger" by Bora Chung, recommended by Anton Hur

Introduction by Anton Hur

Lady Gaga was once asked what she meant by “disco stick,” and she replied, “It’s a penis.” The Korean title for “The Frozen Finger” could either go singular or plural, but I chose singular while translating it because it sounded more phallic to me. But after the galleys were in and it became too late to change anything, I wondered if, indeed, fingers plural would’ve been better for this particular story, as the patriarchy is a system of dicks and not one giant dick? Or is the patriarchy one giant (or small) dick?

Because to me, this very simple story is a razor-sharp allegory for the patriarchy. Patriarchy is an institution, institutions are systems, and systems are cyclical—they repeat themselves. It’s also the fact that the narrator starts off in the driver’s seat, the seat of control and power, but gets tricked out of it by the frozen dick. It’s how she almost gets killed by desperately looking for her wedding ring—rings are another cycle and marriages are often tools of patriarchal subjugation—and, spoiler alert, how she gets killed anyway by the machinery that is weaponized misogyny. More than anything else, it’s the initial politeness of the finger(s), the conversation that slides into gaslighting, the darkness, and the prevailing sense of dread that makes the frozen finger(s) the most pared-down metaphor you can hope to come up with for the system of dicks that subjugates us all (but especially subjugates non-men).

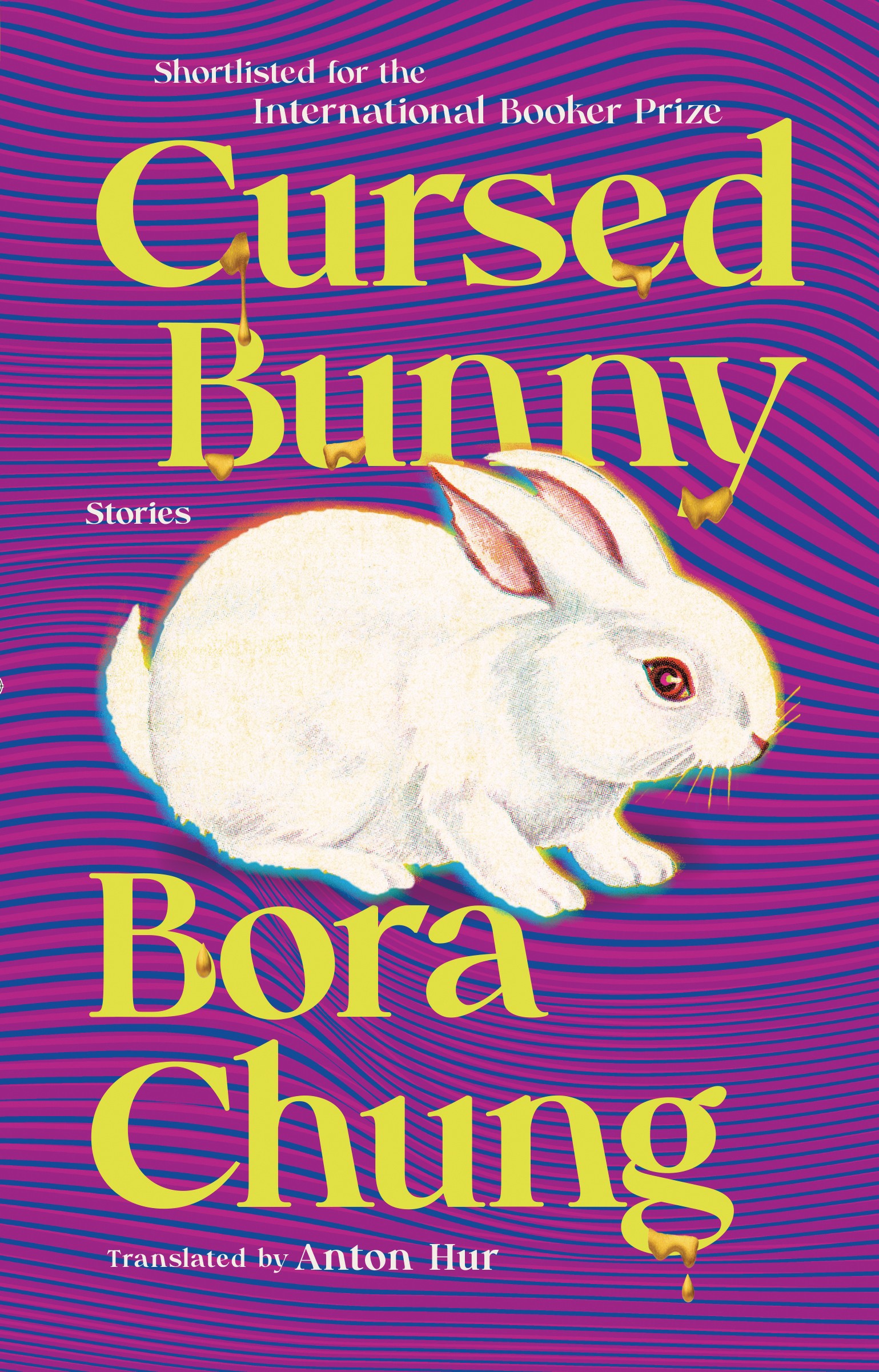

Whenever I ask Bora Chung, the author of this story, about the “intention” and “subtext” of any of her creative works, she tells me there is no “intention” behind any of her work. When I answer her with the “Sure, Jan” look, she goes on to talk about contemporary literary theories about the author—which for years she taught as a college instructor—and how no one cares anymore what the author thinks or what readers are “supposed” to get, how it only matters what the reader takes from the text. She gave me next to no instruction on how to translate her book, Cursed Bunny, out now from Algonquin Books; she was less interested in her “intention” being translated and more interested in what my own reading would be.

Lovely Recommended Reading introductions aside, authors usually have no way of communicating directly with the reader as they’re about to read the work, and the story will always be what the reader makes of it. But yes, if you were to ask me about “The Frozen Finger,” I would with some confidence as the official translator answer: “It’s a penis.”

– Anton Hur

Translator of Cursed Bunny

If On a Country Road a Car Crash

Bora Chung

Share article

The Frozen Finger by Bora Chung, translated by Anton Hur

She opens her eyes.

Darkness. Pitch black. Like someone has dropped a thick veil of black over her eyes. Not even a pinpoint of light to be seen.

Has she gone blind?

She tries moving a hand in front of her face. There does seem to be a faint object there. But nothing she can clearly discern.

After a few more attempts at this, she gives up. The darkness is simply too dense.

What hour could be so dark? And where in the world . . .

She extends her arm and probes the space before her.

A round thing. Solid.

A steering wheel.

She slips her right hand behind the wheel. The ignition. Her keys are still in it. She turns them. No response. The engine is dead.

Her left hand prods the left side of the wheel. It grips something that feels like a hard stick. She pulls it down. The left-arrow on the dashboard should have lit up. No light to be seen. She pushes it down. Still no light. She feels her way to the tip of the lever and turns the headlight switch. And of course, the lights do not turn on.

What has happened?

She tries to remember. But her memories are as dark as the scene before her.

“—eacher.”

A woman’s voice, thin and frail. She looks up. The voice calls for her again.

“Teacher.”

Craning her head toward the voice, she strains her ears attempting to determine where it’s coming from. But the voice is so thin that its direction is unclear.

“Teacher Lee.”

“Yes?” she answers. She can’t make out where the voice is coming from, who is speaking—or whether the voice is in fact calling for her. But the sound of another person’s voice in the darkness is such a relief that she finds herself answering before she can stop herself.

“Are you there? Who are you? I’m over here!”

“Teacher Lee, are you all right?” The voice is coming from the left. “Teacher Lee, are you hurt?”

She tries moving her arms and legs. No pain anywhere in particular. “No.”

The thin voice, still coming from the left, says, “Then come out of the car, quickly.”

“Why? What happened? Where am I?”

“We’re in a swamp,” the thin voice patiently explains, “and the car is sinking, little by little. I think you better come out of there.”

She tries to get up. The safety belt presses down on her torso. Tracing the belt to her waist, she presses the release and the safety belt disengages. She turns to the left and gropes around for the door handle. There, the glass pane of the window. More prodding, downward.

“Teacher, you must hurry.”

The door handle. She pulls it. The door doesn’t move. She pushes it.

“Teacher Lee, hurry!”

“The door won’t open.”

She doesn’t know what to do.

The thin voice commands, “It’s locked from the inside. You must unlock it.”

Feeling around the door handle again, she can feel the protrusions of buttons; she presses them, one by one. At the third button, she hears a clunk. The brief vibration felt through the door is as welcome as the Savior Himself.

She pulls at the door handle again. The door seems to open little by little. But it’s blocked by something.

“The door won’t open,” she says, pushing it with her shoulder.

From right beside her, the thin voice says, “That’s because the car is lodged in mud. Let me help you.”

Someone’s finger brushes against her hand that’s pushing the door. The door opens a little more.

“Quickly. Get out of there,” says the thin voice.

Doing as the voice commands, she brings her left leg out of the car first before suddenly remembering something.

“Wait . . . wait a second.”

She crouches down in the seat and starts to grope around beneath the steering wheel. The long thing on the right is the accelerator, the wide thing on the left is the brake. She stretches her right hand into the space below the pedals. She can feel the scratchy mat and the mud smeared on it. Of the thing she is searching for, nothing.

“What are you doing? You must get out of there immediately!” The thin voice is getting anxious.

“Just wait . . .”

Extending her hand even further beneath the seat, she feels a long, thin steel rod. It’s probably the lever that adjusts the driver’s seat, moving it back and forth. She feels underneath it. Again, just the mat and mud, plus a little dust.

She can feel her left leg, the one that made it outside the car, slowly start to rise. The car door begins to close with it, putting pressure on her left leg.

The voice shouts, “Teacher Lee, hurry! I don’t know what you’re looking for, but just leave it and come out!”

“But . . . but . . .” She can’t bring herself to say it.

“But what? What is it?”

“Something very important . . .” Her voice trails off.

She touches her left hand with her right. There’s no ring on her left ring finger. Her hands feel about the driver’s seat where she’s sitting, then the passenger side.

“What could be so important? What is it?” the thin voice asks again.

Her left hand grabbing the frame of the car, she stretches her right arm as far as she can to beneath the passenger-side seat.

“A ring . . .”

Her hand can’t reach as far as the other seat; all she can grasp are the gearshift and handbrake. She manages to stretch her arm a little further. There’s no one in the passenger-side seat. Perhaps because of her odd posture, her hand can’t quite reach the bottom of the other seat.

The finger from before touches her left hand again.

“This. Is this what you’re talking about?”

A small, round, and hard object against her skin. Someone’s fingers slip it onto the ring finger of her left hand.

She sits up and touches her left hand with her right. It’s still impossible to see, but the smooth touch and the slightly uncomfortable thickness pressing against her fingers feels familiar.

“Is this it?” asks the thin voice.

“Yes. How did you—”

“This is it, right? Come out, quick. It’s dangerous,” says the thin voice urgently.

With her right hand, she pushes the slowly closing door. She barely manages to squeeze the left side of her body out the door.

“Be careful,” warns the thin voice. “The ground outside isn’t solid.”

Her left foot lands on the ground with a plop. She shoves the car door with her left hand and the car frame with her right, slowly getting out of the car.

With every step, her feet sink into the ground. It’s hard to keep her balance. Just as she’s about to stumble, the frozen fingers grab onto her left hand.

“Be careful. One step at a time, slowly.”

Doing as the voice instructs, she takes one tentative step at a time, moving further and further away from the car.

Suddenly, she stops.

“What’s wrong?” asks the voice. “Did you . . . hear something?”

“Hear what?” the voice asks again.

“Someone . . . I thought there was someone there.”

The thin voice is silent, as if pausing to listen. Then, it says,

“You’re mistaken. There’s only the two of us here.”

She listens again.

The sound is vague. Somewhat far away in the distance, or right by her ear, something like a human voice, or the wind . . .

The sound withers into silence.

“I’m so sure there was someone there—”

“There’s no one here except us,” the voice says adamantly. “If you think you heard something, it might have been wild animals.” The fingers gripping her left hand give a squeeze. “I think . . . we should run away from here.” The voice sounds afraid.

Fear seeps from her fingers through her hand, moving up her arm and into her heart.

Fear seeps from her fingers through her hand, moving up her arm and into her heart.

Wordlessly, she begins to walk.

Her feet occasionally sink into the unstable ground, almost making her fall. Whenever that happens, the fingers, gripping her left hand so hard that it hurts, hold her steady and help her find her balance.

There is no way of knowing where they are going. Nor of determining where they are. But the thin voice sounds as frightened as she feels, and the fingers that grasp her left hand feel dependable. And so, she decides to believe in the voice and fingers as they walk together over the pitch-black ground into which their feet sink, going further into the unknown.

“Ah, here we go,” the voice says, reassured. “The ground is firmer here.”

That moment, her left foot lands on firm ground. Then, her right.

“It’s so much easier to walk,” says the voice, delighted.

“Shall we rest a bit?” she suggests. Walking endlessly through mud into which her feet keep sinking was exhausting for both the body and soul.

Without waiting for an answer, she sits down on the road. The owner of the thin voice sits down next to her. She can’t see her, but she can sense her sitting down.

“That ring. It must be very important?” the thin voice asks carefully.

She fondles the round, hard, and smooth object on the ring finger of her left hand.

“Well . . . yes.”

The thin voice asks again, still careful. “Is it . . . really that important?”

“Well . . . I mean . . .”

Her hand keeps touching the ring finger.

A large, warm hand, memories of that hand wrapped around her own, a familiar face she was always glad to see, such pleasure, such happiness . . . Something like that. An important, precious something, like . . .

But the more she tries to recall these memories the fainter they become, and like the last rays of the setting sun, they disappear leaving just a trace of their warmth behind. The only thing left in her mind is that which has ruled her and surrounded her since the moment she opened her eyes: the darkness.

As she keeps silent, the thin voice apologizes.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to pry—”

“Oh . . . it’s fine.”

She is beginning to feel like something is wrong.

“I just . . . I can’t remember . . . My mind is so dark—”

“Oh no. Are you hurt?” The thin voice sounds worried.

“But . . . I’m not sick at all.”

“Let me see.”

She can feel the fingers touch her forehead and scalp.

“Does this hurt?” asks the thin voice.

“No.”

The fingers tap her temples. “What about here?”

“It’s fine—”

“Oh no . . .” The voice sighs lightly. “We should get out of here quick and go to a hospital as soon as possible.”

She touches her own head and face. There doesn’t seem to be any wounds, and she doesn’t feel any bleeding. There is only the darkness that permeates her mind.

“Um . . . excuse me,” she says after touching her face and head for a bit. “Where . . . where are we? What happened to us?”

“Oh my, you don’t remember?” The voice seems surprised.

“Not a thing,” she answers listlessly.

“We went to Teacher Choi and her new husband’s housewarming party and got into an accident on the way back . . . You really don’t remember?”

“No.”

Nothing, she remembers nothing. She turns the inside of her head upside down, looking for something. All she finds is darkness and yet more darkness.

“Uh, Teacher . . .” The thin voice sounds uncertain. “Then you . . . you don’t remember who I am, do you?”

She hesitates. She wants to cry. “I don’t.”

“Oh my, what are we to do . . .” The thin voice becomes even thinner, as if sapped of strength. “I’m Teacher Kim . . . in the class next to yours, Grade 6 Class 2 . . . You don’t remember?”

“I’m not sure.” So “Teacher” meant elementary school teacher, she thinks to herself.

The thin voice becomes urgent. “Teacher Choi, she taught Grade 5 with us, and then quit after getting married . . . She followed her husband out of Seoul. You were invited to their housewarming, so you came along. . . You really don’t remember?”

“I don’t know.”

“This really is serious.” The fingers touch her left hand again. Like before, their grip is firm. “We should get up.”

“What?” She is up on her feet before she knows it.

The thin voice is adamant. “Teacher Lee, I think your injuries are more serious than we realize. We shouldn’t waste any more time—we should get up and find a hospital.”

“Oh.”

“Are you very tired?”

“What? Oh, no, not—”

“Then let’s go.” The fingers gently tug at her left hand.

She begins to follow.

As she walks, she asks, “So, how did we get into this accident?”

The thin voice sighs. “I don’t know either . . . I drank too much, which is why you were driving.”

“Oh.” Her guilt blocks her words for a while. After a pause, she asks again. “Then that . . . that car. Is it yours, Teacher Kim?”

The voice doesn’t answer.

Feeling rebuffed, she stops asking questions.

But after walking in silence for a moment, she can’t help asking again. “Where . . . where can we be, do you think?”

“Well . . .” The voice seems reluctant to answer.

She persists. “Teacher Choi’s house, where is it exactly? Is it close to here?”

“Well, the thing is, I don’t know either . . . I fell asleep as soon as we left . . .” The voice’s answer trails off.

She thinks a bit more.

She asks, “Do you happen to have a phone?”

The voice does not answer for a moment. Then, “A phone? No. Do you have one, Teacher Lee?”

“I don’t either.”

The voice asks, “Did you not look for it when you were searching for your ring?”

Sensing a shade of reproach, she answers, “There was nothing in the front seats . . . What about the back?”

“It was too dark to look. It could’ve flown out the window.” But the voice seems uncertain.

The conversation stops again.

She has no idea how long they’ve been walking since leaving the car behind. All around them, it is still complete darkness. No risen moon, no stars. How long do we have to wait until daybreak, she wonders.

“Where . . . where exactly are we going?” she tentatively asks.

The voice doesn’t answer.

She asks again. “Do you. . . do you even know where we’re headed?”

For a moment, the voice doesn’t speak. Then, instead of answering her question: “Teacher Choi, I feel sorry for her.”

“Excuse me?” She’s taken aback.

The thin voice mumbles as if it isn’t meant for her to hear. “So happy when she got married, like the whole world belonged to her, but then divorced within a year, quitting her job at the school . . .”

She waits. But the voice does not continue.

So she asks again. “Um . . . what are you talking about?”

The thin voice mumbles again. “It’s not her fault that her husband had an affair . . . Don’t you think it’s unfair? They say a teacher must always set an example, but she’s a woman, after all. A divorced woman, at that . . .”

“What are you talking about . . . Didn’t you just say Teacher Choi was a newlywed?”

The thin voice laughed a thin laugh. “I suppose she is, if it was only a year ago she got married—”

“But, just now, you said Teacher Choi just got married, we were at their housewarming party . . .”

“Oh Teacher Lee, you must’ve hit your head rather hard.” Patiently, the thin voice explains. “Teacher Choi got divorced, went alone down to the countryside, and we were visiting her in her new room, as both a housewarming and consolation. . .”

After a moment of silence, the thin voice starts mumbling again. “Living alone turned her into such a lush, all that drinking she did . . .”

She is flummoxed. “But, but—”

“You really don’t remember anything?” says the thin voice. Then, muttering, “Oh my goodness, we really ought to take you to the hospital, quick.”

The words make her shut her mouth.

There are no more words as they keep on walking.

She stares at the sky as she walks. It is so dark that she has no idea whether what she is looking at is, indeed, the sky. She thinks of how she has never known such a darkness before in her life. If she has indeed been in a car crash, that would mean she’d been on a road, but how can there not be a single streetlamp?

Where is she? And where is she walking to?

“Teacher Choi, such a shame . . .” The thin voice, walking in front of her, is speaking again.

She doesn’t answer.

“Her mother, she kept crying . . . She was so young, and to die so horrifically—”

Interrupting sharply, “What are you talking about?”

The thin voice sighs. “You saw it, too, Teacher Lee, at the funeral . . . Oh, right, you said you don’t remember.”

Hearing a mocking tone at the trailing end of the voice’s reply, she fiercely counters with, “Why are you talking about a funeral? You said it was a housewarming, earlier—”

“You really must have hit your head hard.” The thin voice tsk-tsked. “I understand if you like someone for a long time, but to kill yourself over a crush . . . So young at that, the poor family—”

“Didn’t you. . . didn’t you say Teacher Choi was married?” she says, forcing her trembling voice to sound firm. “That her husband had an affair, that she got divorced . . . Isn’t that what you said?”

The thin voice lets out a thin breath.

“Whew . . . What on earth are you going on about . . . You should know better by now.”

“But you said so earlier. You said it was Teacher Choi’s housewarming as a newlywed, then it was her room . . . You said she was married, then she was divorced . . .”

“Teacher Lee, you’re talking in circles. Does your head hurt a lot?”

She shuts her mouth.

“Teacher Choi . . . such a pathetic tale, don’t you think?” mumbles the thin voice after a pause. “Even with those rose-colored glasses of hers, you would think she’d seen how blatantly her man was getting it on with the teacher in the next class. The whole school knew about it, but she was really stubborn in her denial . . . Then when that other woman stole her man, she quit teaching and kicked up that whole fuss about killing herself . . .” The thin voice briefly pauses.

She waits.

“Then she really killed herself . . .”

She can’t tell whether the thin voice is suppressing a sob or a laugh.

She feels a sharp pain as the brief but intense trust she felt for the thin voice is torn in two. Fear digs into her heart. Carefully, she steps aside a little to the right. The thin voice from her left keeps mumbling as if she isn’t there.

“Life, really, is so unfair. Everyone is born the same way, but some steal husbands, others are sucked dry and spat out like used chewing gum . . .” She doesn’t answer.

The thin voice keeps talking. “Isn’t it funny? Two people are in the same car accident, but one lives to tell the tale, the other dies on the spot—”

“You. Who are you?” She cannot suppress the shaking in her voice anymore.

The thin voice casually goes on. “Don’t you think it’s so unfair? Alone when alive, and still alone when dead.”

“Where is this place?” she shrieks. “What’s happened to me?!”

The thin voice on her left gives a thin cackle. “People, you know, they’re so funny. Don’t you think? Just because they’re afraid, they go about trusting in any old voice they hear around them, even when they can’t see for the life of them.”

“What are you?” She is shouting now. “Wh-where is this? Where are you taking me?”

The thin voice continues to cackle. “Following a strange voice around in a strange place, just because it pretends to be kind . . .”

She cannot stand it anymore. She begins to run.

The voice keeps cackling behind her and mumbling. “She doesn’t even know who she is, or where she’s going . . .”

She runs. She doesn’t know where she’s going but feels some relief at how the voice seems to be getting farther away, and so she keeps blindly running.

She runs. She doesn’t know where she’s going but feels some relief at how the voice seems to be getting farther away, and so she keeps blindly running.

The ground beneath her feet suddenly caves in. She stumbles momentarily. After a bit of flailing she rights herself, and a bright light suddenly fills her vision. Her eyes, so used to the dark, lose all their function in the sudden glare. She freezes in the flood of light.

For a brief second, she sees clearly straight ahead—her own self sitting in a car that’s lost control, barreling toward her, her expression frozen in fear, her hands ineffectually grasping the steering wheel where a third set of five fingers, mockingly casual, are holding the wheel between her two hands.

Then, darkness again.

“—eacher.”

A woman’s voice, thin and frail. She opens her eyes. The voice calls for her again.

“Teacher.”

It’s the voice again. She tries to turn her head to the direction the voice is coming from. Her neck, however, doesn’t move.

“Teacher Lee.”

Before she can speak, a familiar voice answers.

“Yes?”

Hearing her own voice answer the thin voice, she feels like her whole body is convulsing underneath the car. But her body doesn’t move. A slimy mud, or something that is like mud but nothing she can ever know for sure, is making its sticky, stubborn, and ominous way over her ankles to her knees, thighs, stomach, slowly but ceaselessly crawling up the rest of her body.

She can hear conversation from afar.

“Are you there? Who are you? I’m over here!”

“Teacher Lee, are you all right?”

She tries with all of her might. Her right arm is pinned down beneath a wheel. She just about manages to free her left hand. It grips the bumper. Trying to pull herself from underneath the car, she puts all her strength into her left arm.

Suddenly, cold fingers touch her left hand. She makes a fist. But it’s too late. The cold fingers have wrested the round, hard, and smooth ring from her hand.

“No . . .” She tries to shout it. But her voice has crawled down her throat.

The thin voice whispers into her ear, “You’ve been hurt badly, you really shouldn’t move. Tea. Cher. Lee.” It cackles softly as it moves away from her ear.

She feels slight vibrations from the car that covers her. “Be careful. One step at a time, slowly.” It’s the thin voice, from a distance.

She opens her mouth. With all her strength, with all the fear and rage and despair pooled in her heart, she screams.

“What’s wrong?” she can hear the voice ask. “Did you . . . hear something?”

“Hear what?” the voice asks again.

“Someone . . . I thought there was someone there . . .”

She can just about hear heavy footsteps coming down on soft ground. The conversation becomes more and more distant.

The car sinks. She hears the sound of bones breaking somewhere in her body. Strangely enough, the sound makes her realize she no longer feels pain.

All she can feel is the enormous weight of the car as it drags her down into the unknown abyss.