Lit Mags

If You Didn’t Wanna Get Evicted, You Shouldn’t Have Ruined My Life

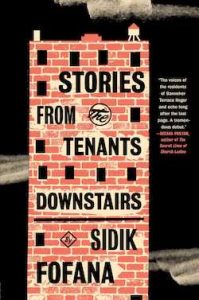

"Tumble" from STORIES FROM THE TENANTS DOWNSTAIRS by Sidik Fofana, recommended by Deesha Philyaw

Introduction by Deesha Philyaw

“Tumble” is one of the eight compelling linked stories in Sidik Fofana’s excellent debut collection, Stories from the Tenants Downstairs. In this story, a violent scene involving a character getting “stomped out” conjured up some not-so-fond memories for me. Despite four decades separating my childhood in Florida from gentrifying Harlem where “Tumble” is set, Fofana’s deceptively lean prose took me right back to that first day of school when a girl named Pam ambushed me as I stepped off the school bus. Mercifully, I have no recollection of what happened, but my friends told me Pam clobbered me.

My crime, it seems, was thinking I was cute. We were all poor, but my mother had sent me out into the world looking more put together than Pam. As I said, I don’t remember the beating; I was in first grade, Pam was in second. Low stakes compared to what happens in “Tumble” among teenagers who carry deep resentments and even deeper generational wounds.

My crime, it seems, was thinking I was cute. We were all poor, but my mother had sent me out into the world looking more put together than Pam. As I said, I don’t remember the beating; I was in first grade, Pam was in second. Low stakes compared to what happens in “Tumble” among teenagers who carry deep resentments and even deeper generational wounds.

What happens to a dream deferred thanks to the cruel betrayal of a former childhood friend? What do justice, empathy, and forgiveness look like within a community when traumatized, violated people turn around to traumatize and violate those closest to them?

These are some of the weighty questions I’m still sitting with after reading “Tumble.” Of his collection as a whole, Fofana told Publishers Weekly, “The theme linking the stories is the American dream and the disillusionment of the American dream.” In particular, the collection focuses on the dreams and despair of the Black tenants of Banneker Terrace who are at risk of losing their homes due to gentrification. Neisha, the main character of “Tumble,” is one such tenant, a young woman who recently quit college after two years. Grudgingly, Neisha now works for the Committee of Concern, a group of older women tenants seeking to halt the building’s accelerating evictions.

Neisha, once a rising gymnast whose pride brought her into direct, violent conflict with her former friend Kya, bristles constantly, feeling “like a disappointment” for having moved back in with her parents and believing the elders in the community think she “threw everything away.” The same community that celebrated her two years ago nevertheless remarks that she “talks white,” and Neisha has more than a little disdain for them in return. She notes the “hot thuggish guys who would ruin my life” if given a chance, and she refers to her peers’ gathering place as “their little underworld,” “their little dumpster den.”

Even as they all, including Neisha’s family, face eviction, Neisha regards her neighbors and family members with a certain detachment. She believes–wrongly, as the other stories in the collection illuminate–that her ambition sets her apart: “I think maybe I could be something cool like the executive director of the Miss America pageants.”

Fofana has written a beautifully complex story that left me with my allegiances torn. Both Neisha and Kya make terrible choices, but I understand why they choose the way they do. Because the resilience we demand of Black people in this country is too damned much.

– Deesha Philyaw

Author of The Secret Lives of Church Ladies

If You Didn’t Wanna Get Evicted, You Shouldn’t Have Ruined My Life

Sidik Fofana

Share article

Tumble by Sidik Fofana

Usually, they give you time. You might see a notice on someone’s door for the whole year. Now, several units were getting one on the same day.

So less than a week into my time as a building liaison, Emeraldine hands me a printout of Banneker tenants who got notices in the past month—twentysome in all. She does it with this attitude like she’s waiting for me to object, but I just take the list and act like the new worker who’s happy to get work.

We gonna start setting those folks up with the Citizens Legal Fund, she goes.

I hold up the list doing my best to murmur the names. Michelle Sutton, Darius Kite, Verona Dallas. Then I get to one that cold knocks me out. I move it close to my face to make sure it’s not a mistake. Kya Rhodes.

Ever since I quit school and came back Emeraldine’s been constantly on me. Everybody’s supposed to be like her, gung ho for change. She thinks I threw everything away.

I didn’t even wanna work for the Committee of Concern. I wanted to work for a magazine, interviewing celebrities, but every magazine from Fifth to Eighth Avenues treated my résumé like it was invisible. If I hadn’t seen the clipping in the lobby, I would have had to cut my losses and been a Macy’s perfume girl.

So now I’m fielding phone requests. I’m cleaning out the communal fridge. I never thought I’d be stuck working with three old ladies. One who thinks she’s Cleopatra and is always looking at me over her glasses.

I was a division one gymnast and now I’m back living with my parents. I already feel like a disappointment. But this Kya thing seriously paralyzes me.

Emeraldine and Corinthia said she was holding on by one tooth. That they saw her at the Dunkin’ Donuts begging the cashiers not to throw out the leftovers. That her mother died and left her with a hefty casket price. I should be empathizing but I was tuning out. I can only concentrate on how it’s been two years since I saw her, and the last time wasn’t good.

That Sunday after I got the list, we throw a luau-themed cookout in the back of the building to calm tenants down about all the evictions. Our building got sold to new owners, so now all our places are basically being prepared to become deluxe apartments in the sky. All of a sudden, you look next door and a wreath you’ve seen all your life is gone. People haven’t been taking it well. Lots of loud last parties. Lots of slanted box springs in the hallway. Not too long ago someone lit a ball of yarn on fire in the laundry room. I don’t blame them. That kinda thing would hurt anyone’s psyche.

Anyhow, I help cover the bazaar tables with plastic straw and set up the serving trays. Emeraldine and Corinthia wear hula skirts. Raspreet brings this really cool sculpted cane from her country and a ukulele. Children are rolling around all cute with their faces painted. Hot thuggish guys who would ruin my life are sitting on lawn chairs in socks and Nike sandals. Somebody brings their boom box. Everyone’s enjoying the food and the breeze.

It feels like people are staring at me, and it’s not because I’m a grown woman and I’m tiny. I’m already used to everyone thinking I talk white.

The whole time it feels like there’s a girl with over-Vaselined lips waiting to pounce on me.

I actually call in sick the Monday after the luau cookout and stay upstairs. I grew up in this apartment with my mom, dad, brother Timmhotep, and Rerun, our female shih tzu. My parents were Black Panther sympathizers and gave me the name Quanneisha because they felt it was strong and powerful. I shortened it of course. My mom does janitorial work at the Sydenham clinic and my dad has a table on Adam Clayton where he sells incense and sometimes phone cards.

Taking the day off is dicey because my parents weren’t thrilled about me dropping out in the first place and said I could only stay if I kept business hours. Ma’s not home because they needed an extra person at the hospital to mop the labs. With my brother still in Arizona, I can put the divider sheet up and have both sides of the room. I wait for my dad to leave, so it could just be me, Rerun, and her slobber.

But that doesn’t work because right when my dad is heading out to set up his stand, he gives me one of his looks and goes, You been takin Rerun out?

I have been, I say. I do it real early in the morning and real late at night.

What about your friends from school? You see any of them yet?

Not yet.

For a second, he is about to dwell on it, but decides against it and undoes the door chain.

Well, don’t stay in here all day, he goes. There’s a world out there just waitin on you.

I try to say, Hey, Neish, you’re a tough girl. I was tough since the day I knew I wanted to be a gymnast when I saw Kerri Strug on TV. I thought it was so awesome how she lifted her hands to the sky like, hey everybody, come hug me. I was eight years old. That same afternoon, I backflipped off this broken slide and landed on my feet. I wish I could say that’s all she wrote, but you just don’t hop around in a playground in Harlem and ta-da. Nobody’s gonna go, Look at little Neisha, let’s nurture her. When I saw that flyer at the Central Park Zoo that said Come one, come all, tumble away, I literally had to snag it down before my teacher reported me missing. I remember the night I showed it to my mother who wasn’t against slapping the foolishness out of anyone.

Oh no. Not gonna happen, sweetie.

You don’t know what it’s about!

I don’t know what it’s about, she said, but I know how much it costs.

That would have been the end of that had she not seen the line my brother scribbled at the bottom which was: she get to do backflips with rich girls. My brother who you only heard when his Sega Genesis was overheating.

My mother finally relented, and I wound up at a gym in Midtown with all these girls in polka-dot and neon leotards, and me in jean shorts. Straddling the uneven bar for dear life until I hear my shorts tear. I had to be tough. Everybody thinks you’ll automatically become that Black girl who’s the best. But you really have to watch out because otherwise, you might be that urban girl who tries to hang, gets over her head, and quits.

I only ever invited Kya to a meet once when we both were around ten. We were only three months apart in age. She was in the courtyard one day in kindergarten and our mothers basically shoved us forward to shake hands. It was awkward because just seconds ago, her mother was cussing her out. Normally, my parents would call that a red flag, but we were the only two children out that day, and it would have been kinda rude not to say hi. From there, we ran into her and her mother coming from the 2 train. Every summer next to the jungle gym and sand the homeless people peed in, we’d parlay while my mother watched me from the lobby window. I’d do a somersault for Kya and she’d say, Whoo! Wow! And you not even afraid of falling!

I spent most my time training and at a prep school one of the dads at Midtown Gymnastics helped me get into, in other words not around Black people. I was fascinated with Kya, how even in the fifth grade her voice sounded like it was filled with concrete. How Ashanti would come on out someone’s window, and she would start dancing lazily and effortless, like she was possessed by a rhythm she didn’t even want.

I trained six days a week, six hours a day for eight years straight. I was constantly taping myself up and falling these ghastly falls. Some days I felt like I couldn’t even move. Some days, I felt like an absolute beginner. I hardly focused on school. I killed my body. I spent a good part of my life in tears. But I fought through it. I ate my soy and listened to my Ramones. That’s what I did all of high school and it paid off.

I was in the student lounge at school the day a local magazine announced I was invited to Nationals. At Banneker, they hung a banner from the front wall of the bingo room. Somebody from the public access channel came by and interviewed me. Tenants kept asking me for photos and to backflip.

Kya, on the other hand, was up to smoking Newports and wearing expensive blouses that still had the tags on them. Her crowd was seedy, but she always said that they were just her friends and she wasn’t like them. That week that the building put the banner up for me, she hung with a bunch of other teens in black bandannas out back by the dumpsters on beat-up lawn chairs drinking and slap boxing. They knew about me. They saw the banner. But they were fine in their little underworld. One evening, I saw them out there sitting on each other’s laps and I decided to take out the garbage. I had my headphones in and kept my head up like I couldn’t be bothered, but as I passed by them, I accidentally smeared my garbage bag on somebody’s Nikes.

I’m sorry about that, I said.

It was really quiet, but then as I continued, I heard someone repeat, I’m sorry about that, followed by Kya busting out in giggles. It was the giggles that struck me down.

So I said fine.

The very next day I wore a hoodie that the Nationals’ press office sent me. It was eighty-five degrees, but I wore it anyway. Anytime I was in the lobby and any of them was in earshot, I made it a point to use big words. If I was posing for a picture with somebody and one of them was behind me, I’d take my sweet time.

Then Kya’s boyfriend kissed me. I swear I didn’t ask for that. He taps me on the arm in the elevator when I’m minding my business and goes, You that acrobat girl, and I go, You mean gymnastics, and he goes, Bet you be doing that stuff naked, and right in the middle of me telling him and his boy I wasn’t the one, he kisses me, which of course gets back to Kya’s ears as the other way around.

Two weeks before Nationals, I go to take Rerun for a walk out of the back entrance at night. I bend down to fix her collar and when I get up I’m surrounded by a whole bunch of black bandannas. Kya is in the background. Her friend Princess gets in my face and goes, So you wanna mess with people’s mans? then knees me in the gut.

They’re kicking and punching, but then they grab hold of my hoodie and start pulling it off. Once they did that, one of the girls takes it to this parked car and wraps it in the axle like it’s some rag and when it’s nice and dirty one of the boys throws it on the floor, takes out his penis, and pisses on it. I’m 100 percent sure they would have picked it back up and thrown it on me had a woman not walked by and yelled, What’s going on over there?

The very next evening, I’m back at their little dumpster den and flanked beside me are two cops. There they are, I go, looking everybody in the eye. I look Kya in the eye the longest. It’s not until the handcuffs come out that she realizes what’s going on.

I’m a teenager, she blurts out. Please!

The last scream is so shrill, it vibrates my ribs. I was this close to telling the cops never mind. But I didn’t. Her eyes were violent and dead. It should have satisfied me, but it did nothing. I had a muscle contusion and fractured wrist. I tried to continue training for Nationals, but I couldn’t get through any of my routines. The day I withdrew my name, I sobbed all night. My teammates tried to cheer me up. You’ll get another chance, they said, but I was seventeen. As I powdered up for my Michigan meets that fall semester, I told myself, Neish, look where you made it all the way to. A free education. Those crowds would be blazing with spirit, but I could only concentrate on the empty seats and half-assed it. Right before our northwest showcase, I quit. I walked the campus the whole next year as an ex-gymnast. Then I quit school altogether.

Work with the committee drags on for about a week until the town hall on the first Wednesday of the month. Usually, the town halls are about repairs or pests or mail getting put in the wrong slot, but the last time the evictions hogged the show. They had to start moving the meetings to the Y on 135th because people were on top of each other.

You owe it to yourselves! Emeraldine starts her speech that night in the gym to, like, a hundred tenants in grays and blacks. Why are you suffering on an island? Why are you letting your landlord win? You wanna be sweet-talked? You wanna be slapped around with hikes?

She gestures with her chin for me to usher the standing guests into seats, but I ignore her.

I don’t get a joy of saying I told you so, she continues. I don’t get a joy out of seeing you kicked out. I don’t get a joy out of seeing you get washed away. Not when that same wave’s coming for me, too. But we’re working for you. See that young lady back there. Remember Neisha Miles? Well, she’s back and I’m gonna have her go door-to-door and set up anyone in danger of eviction with a free lawyer. You’ll be seeing her face a lot. All you have to do is trust us.

Everybody turns to look back at me. All I hear is chairs, and I’m seething.

After the whole thing is over and she’s patted everybody on the back for coming from work and has kissed all the babies, Emeraldine pokes my shoulders hard while I’m unplugging the sound system and goes, Are you ready for this mission?

I’m thinking, To help the girl who cost me a shot at being a professional? The girl who would probably attack me? No. I almost ask to trade her with someone else, if it didn’t mean she’d probably get helped.

I half nod.

For the next two days, I print tenants’ rights leaflets. I reach out to the Amsterdam News. I organize the office and field phone requests. I write down the logistics for a flea market that isn’t supposed to happen until the end of the summer. I flyer the bulletin board.

During idle moments, I look up schools in New York. I think about my future. I always thought I’d be an Olympian, but obviously that’s not possible anymore. I think maybe I could be something cool like the executive director of the Miss America pageants. In high school, I got B pluses. I wasn’t the queen of work ethic, but I wasn’t a goof. Anyhow, I find a list of CUNYs and have a mild interest in a couple of them, but with no scholarship I would have to pay out of my own pocket.

I tell myself that I have no choice but to concentrate on this job until I get my act together. In the meantime, I pretend that the list is a mistake and Kya isn’t really here.

I step outside one night to meet some friends for drinks and I see a girl in the courtyard. I recognize her in a jiffy and there goes the Kya-not-being-here fantasy.

She has on this velour tracksuit that’s worn down and she’s in the company of these thuggish guys. She might have gained weight. I can’t tell. She’s still cute, but her clothes are too baggy. And right there by the tree in the dirt are her kids, drawing circles. She’s having this super loud conversation.

She’s like, I told him, Get these shits out my face. All these shits is blurry! That nigga clumped his shits up like a blanket and was out!

Immediately I’m taken back to the days of her hanging in those lawn chairs in the back by the dumpster.

The guys start howlin. One of them goes, You should of been, like, I change my mind, give me ten of them shits! This really cracks her up, too, and sends her hopping across the pavement to a tree where the squirrels see her but continue gathering their nuts. Her kids are there and she playfully bops them and gives them a hug.

I don’t know what to do. I pretend to forget something and

turn on my heel back toward the building to leave out the back entrance. I think about the night she stomped me out. How afterward, she and her friends taped my buzzer down so it would ring all night. I remember how they passed me in the lobby the next day and this thin girl brushed her shoulders by me with a force from the jungle.

Why is she so animated now? Isn’t her life in shambles?

When it comes time to go to Kya’s apartment I decide that instead of knocking, I’ll slip a generic note under her door and hope things work themselves out.

Days go by.

Corinthia, Raspreet, and I are at the table by the hanging plants, tearing raffle tickets and piling them on a drum from last year’s summer gala. Corinthia loves talking about celebrities whose lives are a mess.

They catch them in the cars with hookers, she goes. Catch them in the broom closet with the maid. Committing insurance fraud. It’s ridiculous. We’re the ones supposed to be frauding. Not them! That’s why I love me some Barack. And some Michelle. And some Serena. And some Venus. And some Flo-Jo. And some Dominique Dawes. And some— Neisha why’d you quit?

I shrug my shoulders and prepare to hear that for the rest of my life.

You must have been better than 99 percent of those girls.

But not better than 99.9, I want to say. Instead, I shrug my shoulders again.

Well, just know they not you. I don’t care how many Wheaties they eat.

Yes, Raspreet says, dumping tickets in some empty Tupperware, I agree to that.

By the way, when you were doing your routines and things, did the camera ever do a close-up and your butt was ashy?

We all bust out laughing at the question and at my answer, which is yes. Emeraldine is by herself on the other side with the board games and the Magnavox. I guess us enjoying each other’s company and her being alone with a stack of boxes from Trader Joe’s gets to her. Like when she’s by herself sometimes humming these low melodies and it looks like the weight of the world is crawling out of her fro.

All of a sudden, she comes to me and says, Neisha, can I speak to you in private?

So I just wanted to give you an update on Kya, she begins, sitting next to me. Who happens to be the only one on your list with small children. I was informed the other day that her tenancy was terminated and the building has started her lawsuit. They gave the thirty days yesterday. Someone can still represent her, but that hasn’t happened because she hasn’t been connected to them yet. I understand she’s on your list?

Yes, but I haven’t gotten around to her.

And why is that?

I’ve been busy.

Oh, okay. I also wanted to let you know Dayanelliz Colon reached out to me the other day saying she finished her Hostos College credits and was wondering if I had anything. I told her what I’m telling you, which is I’m gonna give you a few weeks and we’ll see.

The last sentence stings me and of course everybody in the room can hear it and is pretending there’s nothing in the air but air. Emeraldine gets up and the chair creaks.

I wanna tuck my head down and leave and never come back. I sit there like a scolded child and push my chair away with slow hot embarrassment. All you can hear for the rest of the day is the ceiling fan and everybody else flipping pages.

Well, what is it you wanna be then? my mother asks me later from the kitchen.

I don’t know, I say. But I know this is not it.

You were a hero at sixteen when you got us that free trip to Utah and you were a hero when you got that job downstairs.

Tell that to the boys and girls at Mich who are gonna be lawyers.

Since when were we into other people’s grass?

You don’t understand, Ma.

Understand what?

That stuff matters with people.

Does it matter with you?

Don’t make me answer that.

It’s useless even bringing it up. My parents grew up in a place where a bad storm could take everything you had in a fell swoop and so they were always fine with what they had. Growing up, we ate from a table some wealthy lady gave my dad when he was a mover. My parents’ idea of the ultimate fun is getting together in the living room and watching old videotapes of themselves in someone’s backyard dancing to “She’s a Bad Mama Jama.”

I was proud of you from the third grade when you could read better than me, my dad says from the living room couch where he’s got his blanket and his Mary Tyler Moore rerun. And I was never a slouch at reading.

Thank you, Robert, Ma says.

She scrunches up her eyebrows real serious to me and goes, What is this really about? Are you gonna tell me or do I have to spend hours reading it on your face?

She keeps staring into my eyes like an answer’s gonna magically pop up. It gets so awkward that I just relent.

Emeraldine wants me to help Kya.

And?

I’m not gonna.

And why is that?

Because.

Because why?

This is all her fault.

So you want her to drown?

I don’t want her to drown. I just don’t want anything to do with her.

She cuts off the faucet, and there go the hurt lines running up her face.

Robert, turn that TV off a second.

Listen, love, she goes to me and I swear the whole building is quiet.

I’m with you. But let me ask you something. Is that what you’re gonna let consume your life? A grudge against someone who life done gave them theirs already?

The darts are hitting my heart. I’m this close to just falling on her shoulder. Except I don’t budge. I shift in my chair and look past her.

They tryna take her kids, Kya. Did you know that? She leaves the two of them by themselves while she goes to work. They’re saying ACS should be around here any day. Does that make you feel any way?

Silence.

Look, I didn’t say anything when you quit school. I didn’t say anything after I basically begged Emeraldine to take you. I let you pave your own way. But I’m telling you this. If you’re not gonna have something to do with that woman, then don’t have anything to do with me because that doesn’t sound like anything in my family tree.

And that’s when I start spinning the rim of my coffee mug.

I had two days to report back to Emeraldine. Per her orders, I had to visit every tenant on my list. I had to make sure they had their lease, rent statements, payment receipts, and the eviction notice ready. I was supposed to put them in contact with Jamaal Wesley, and he would follow up.

Raspreet and I decide to meet in the lobby and do our names together. She comes downstairs carrying this big brown bag like she always does, full of lord knows what. She’s always pausing to greet somebody and most of the time it’s like awww, but when she stops this time because a woman’s grocery bag spills and ends up talkin about squash, I speak up.

Raspreet, I go after holding the elevator door open the third time. Raspreet!

Huh?

Maybe we should split up and meet up afterward.

I’ve been to almost every floor in Banneker, but I still get nervous because they always seem darker and dimmer than mine. Like the one where someone was playing a Harry Potter movie on full blast that spooked the mess out of me.

The first door I knock on belongs to a man with a keloid under his chin. His face and the way he keeps talking as if it wasn’t there stays in my head until a woman comes to the next door I knock on mixing something nasty that looks like wet oats. Then there’s the dark-skinned couple from the floor below mine who both happen to be tall and magazine-spread gorgeous. On the third floor, there’s a woman in her fifties named Verona.

What you say your name was again? she goes.

I’m taken aback that everything’s so clean, not that I was expecting dirtiness.

Neisha.

Neisha, you talk funny.

They’re all like, Thank you, thank you, thank you. Everybody I visit is like, Thank you, thank you. Even though some of them have their foreheads down.

In the hallway, Kya’s name pulsates at me. For a second my teeth chatter and I say to myself, This is ridiculous. Just walk up the stairs. I start to stomp my way pretending to be a badass. But everything simmers to the surface again, the back lot, my predicament here, and I just can’t.

I knocked on Kya’s door but nobody was there, I say when Emeraldine checks in the next day about the visits, and in this singsongy way she goes, Luckily, you got a week before Jamaal comes to town.

The following Monday, two representatives from ACS double-park their car out front and take away Kya’s kids. I’m in the lobby and with a few others can see everything from the window. The little girl looks confused. Kya, surprisingly, is as calm as brushed hair until the engine starts. Then she bangs on the car window, goes, I hope you have a good rest of the day stealing people’s families, and watches them pull away.

She spends the whole day outside. The next day, I see her across the street walking by this plastic bag floating in the air. Her kids aren’t there, and it’s like a fact she’s ignoring. I know she’ll get them back in a few days, but I know the eviction is next. I try to prepare myself to live with this, and stand my ground, but a thousand flies invade my heart.

After a tumultuous three weeks, Ma’s fiftieth finally comes and she books the bingo room with streamers, tuna salad, and lopsided cake. She is wearing a purple Mabelina on her head with these floral clusters and ruffles and boy, is she strutting her stuff.

I try to be lively, but there’s only so much revelry I can enjoy. I have a few days to finish my visits, but I’m nowhere close to doing the one that counts. I sit off to the side eating a slice of cake that I know I won’t finish. Ma brings some of her friends by and when she asks if I remember them, I smile, but it’s torture.

Emeraldine had invited herself to the party. At some point, she goes over to the sternos and says, Nobody touched my baked ziti? Oh hell no! Then she heads out to the entrance by the security cam to look for people who might want a plate. I know exactly what she is doing. Moments later, five people come in all humble, looking like they would leave right away if anyone gave them a sideways look. One of the stragglers is Kya Rhodes, unaware of the theater she is walking into.

By now I have seen her a few times since I have been back, but this is the first time we’re in the same room with my dreams unable to protect me.

She’s so out of it, I don’t think she even knows whose party it is. Still, to avoid anything, I stay on the other side of the room until she makes her plate and leaves.

It isn’t until Ma sashays herself upstairs and her bingo friends siphon off the last of the macaroni pie, after chairs are folded and balloons popped, tape scraped off and cloths flopped out, that my last bit of energy brings me to the elevator doors, which thank god just slide open for me. Before I can exhale, I notice a young woman in pajama pants and a New York Knicks jersey already on. It’s her. Her hair is pulled taut in a bun and she’s balancing a cigarette from the corner of her mouth. Nicks and bruises speckle her face. The door shuts.

Our eyes meet. I brace myself for anything. For a confrontation or worse: the smirk that tells me that she knows my life. She stands there doing nothing, but then in an instant recognizes me.

I don’t know what else to do so I nod. She nods back. It’s a sustained nod that shoots inside me. She knows all right. She knows all I ever aspired to be. I stay there flayed until she finally speaks up.

Your mother was in the purple hat, right?

Yes, I mumble.

I almost didn’t recognize her. That was her party down there?

Yes.

She looked like she was enjoying herself.

That’s all she says.

The elevator ascends during this time and opens up to Kya’s floor. There she walks off as quietly as she appears. In the rush to make sense of everything, I realize I haven’t hit the button to my own floor. I go to touch the twenty-one, my head still spinning, only to discover the button already pressed for me.