Advice

How Can Literary Magazines Counter Their Biases?

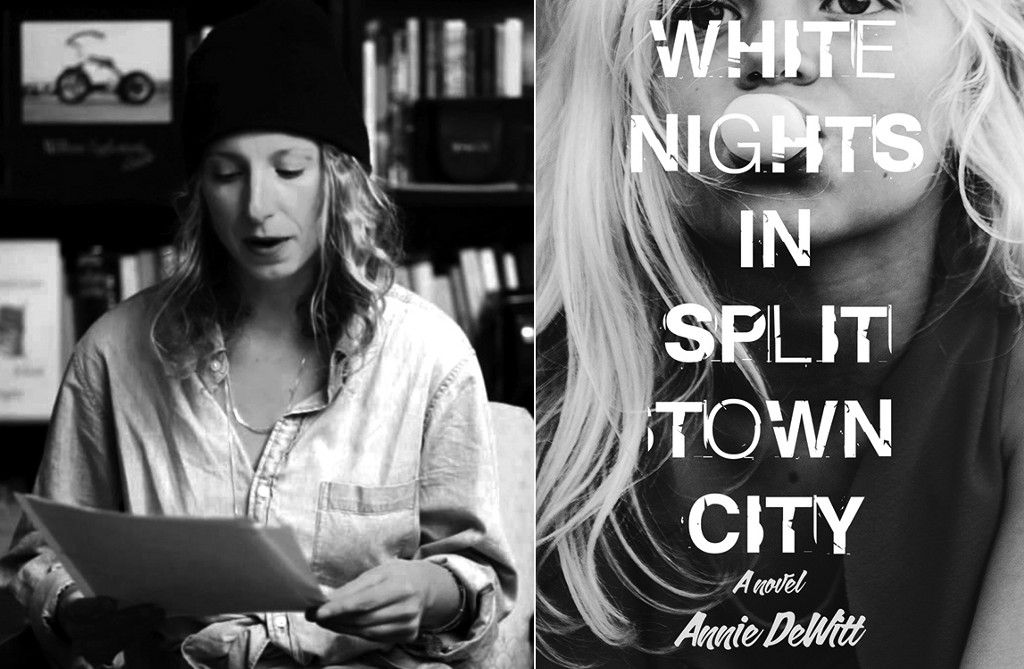

The Blunt Instrument on Blind Submissions & How Editors Can Address Unconscious Bias

The Blunt Instrument is a monthly advice column for writers. If you need tough advice for a writing problem, send your question to blunt@electricliterature.com.

Hi Elisa! Here’s my question. It’s about writing contests. What do lit mags do to counter bias when they run a writing contest? Or maybe, since I’m thinking about how short that answer might be, the question should be: What can they do?

I asked this on Twitter and got, basically, “think about it?” I mean action here. And I mean it on every level, from judges to readers to submitters to contest guidelines and announcements to entry forms to fees and so forth. Maybe that’s guiding the question too much? But I’m interested in whether a “blind” contest actually means bias is less a part of the judging, and I suspect you’re going to say no, so I want to push the question past that to whether or not there are steps that can effectively counter bias, what they are, where the limit is, and where literary magazines stand so far w/r/t addressing this.

You suggested on Twitter that they don’t/can’t. Then would that mean you’re “against” lit mag writing contests? Maybe: if you could imagine an ideal “open to anyone” contest that goes its absolute furthest to combat bias/be “fair” — what would that look like?

Matt Salesses

Hi Matt,

Thanks for sending such a great question. I’d like to start by addressing the question of blind submissions, which I strongly believe are not the answer, at least not in and of themselves, to solving or reducing racial, gender, and other forms of bias in literary contests — but I’ll broaden my answer to apply to literary submissions in general, since these problems are not unique to contests.

There are a number of contexts where judging a submission or application blind (without foreknowledge of the race, gender, or age of the applicant) can do a lot to reduce bias, in some cases eradicating it completely. The most famous example may be orchestra auditions. Orchestras slanted heavily male until it became routine for auditioning musicians to perform behind a screen; now the gender mix is about 50/50. One can assume that before the blind audition process was instituted, women were working against a bias toward male musicians. Similarly, studies have shown that resumes, for example, are reviewed less favorably (and the applicants less likely to get an interview) if the name on the resume sounds female or racial/ethnic — though the qualifications and accomplishments are exactly the same.

Unfortunately, I don’t think a blind process would work quite as well for literature. Two cellists, a man and a woman, might audition with the same Bach piece; they won’t be playing their own music. And there seem to be nearly universally agreed upon standards of what constitutes good playing of Bach, which don’t vary much by gender. If they were each playing music of their own composition, we might run into a problem of bias again: namely, that we have been trained to perceive music written by men as great music. You glimpse this thinking in the common question, “Why are there no great female composers?” (Who says there aren’t?)

Still, the fact that a piece of chamber music might sound, at a subconscious level, more “male” or “female” is subtle and hard to prove. Racial, ethnic, or gendered coding could be much more overt in a piece of writing. For example, if a story has primarily black, Asian, Jewish, or female characters, readers may assume that the author is (respectively) black, Asian, Jewish, or female. A poem that includes phrases in Spanish or Korean will likely lead the reader to assume the author is Latin or Korean.

This kind of coding would interfere with the blind reading process, causing a number of complications: Readers and judges won’t truly be reading “blind” if they can guess the race or gender of the author. Even if those guesses are wrong, they may influence the outcome. We also can’t be sure that it would help even when the judges have the best of intentions. A judge may want to increase exposure for POC writers, and unwittingly choose a story about black or Asian characters that was in fact written by a white man. The big problem is that there is a further level of bias which is harder to recognize and address: We may, consciously or unconsciously, prefer writing by white men, writing that adheres to the standards set by white men and generally upheld by power structures everywhere in literature. We run the risk of judging non-white writing by white standards, deeming non-white writers good and worthy of prizes when and only when they conform to the familiar and established standards of prize-winning white writers.

The unspoken assumption behind blind submissions is that “quality is quality” — that we know “good writing” when we see it.

The unspoken assumption behind blind submissions is that “quality is quality” — that we know “good writing” when we see it. I don’t believe in this idea. We do not have universally agreed upon standards of “good.” There is no ultimate measure of goodness in a piece of writing in a vacuum; its quality is determined within the frameworks of a culture, generally by whatever groups are in power. The standards of quality according to our current cultural frameworks are still racist and sexist; make the work anonymous and we’ll still be judging the writing by how well it conforms to racist and sexist frameworks.

Here’s my friend Adalena Kavanagh on this subject (Adalena is half Irish, half Taiwanese, which you couldn’t guess from her name):

A reader for a lit journal said that if a story has a non-white context, he checks to see the race of the writer — and this is coming from the best place. You can’t tell my background from my name, so I always include my ethnicity in my cover letter, but I resent it. I think: white writers never do this, but I also don’t want a reader at a journal to think I’m doing yellow-face and reject my story because I have an Irish last name. I want to get to a point where all of this is irrelevant! So, completely blind submissions in writing don’t seem like a complete solution now, because our contexts aren’t blind.

To me, this is the crux of the issue: our contexts aren’t blind, so blind submission processes don’t solve the problem. Instead, we must learn to stop judging all writing by standards established by white men; our cultural standards themselves need to change.

With that out of the way, I would like to offer some suggestions as to how lit mags and presses can counter bias when running a contest or reviewing submissions in general:

- First, figure out if you have a problem. Take a look back at both the work you chose to publish and the makeup of your submission pools. There’s a known effect where a 2 to 1 ratio of men to women can feel like about half and half. You may have been publishing two men for every woman and assuming it was about even. Actually do the math. If you’re choosing more men than women, see if you’re getting more submissions from men. That’s not an excuse, but you’ll know if you need to work to change the gender balance in your submission pool.

- Race makes things a little more complicated because you may not be able to guess based on name alone. You can certainly determine the racial breakdown of your published authors, but if you feel like you have a whiteness problem (i.e. you’re only publishing white writers or only getting submissions from white writers), consider asking submitters to name their gender and race when they submit (it doesn’t need to be required). This might give you a better sense of what you’re dealing with. (I would preface such a question with a statement about why you’re asking for the information and how you will and will not use it.)

- If your magazine or press has a history of publishing mostly men or mostly white writers, know that that could affect your submission pool. Based on my own experience, I am much more likely to send work to a magazine or press that doesn’t have a sexist publishing record.

- Consider the races and genders of your editors and, in the case of a contest, both your judges and your first readers. I think having women and POC judges is important both for increasing submissions from women and POC writers and ensuring that submissions are given less biased readings. But don’t forget about your other readers, who may be choosing the finalists to pass on to your judges or final editors. If there’s bias among that group (and there probably is), you’re rigging the contest before it even gets to the judges.

- Think about where (and how) you’re advertising and promoting the contest or calling for submissions. How likely are women and POC to hear about it and feel welcomed by it? (I’m thinking about the jobs page of tech companies which frequently boast of a “work-hard-play-hard” culture, beer on tap, Foosball and video games…basically advertising on appeal to men in their 20s. Could your announcement be advertising on appeal to whiteness unconsciously?)

- If you are a reader or a judge in a contest or an editor in general: Interrogate your own tastes. Taste feels personal but demonstrably isn’t. It is deeply influenced by class, culture, and education. I often hear people say, “Read what you want,” a countermeasure I suppose to sanctimonious advice on what you should and shouldn’t read. But I think part of being intellectually curious is expanding your tastes; I like more and more varied things at 36 than I did at 26.

- Consider your contest fee and whether it’s prohibitive to working, underpaid writers.

Note that all of these questions and problems can be better addressed if there are women and POC on your staff. Don’t rely on a white editor to determine if a contest announcement sounds racist. Don’t rely on a male editor to determine if it sounds sexist.

Finally, I would advise editors to ask themselves why they are running a contest in the first place.

Finally, I would advise editors to ask themselves why they are running a contest in the first place. What is the point? Contests are usually a fundraising measure. But by placing the burden of funding on writers, you are setting up a class bias, since only writers who can afford to submit will. Maybe there’s an innovative way out of this — such as introducing a sliding-scale or “pay what you can” submission fee system. However, even small fees add up, considering how small the chances of winning any one contest are. A pay-to-play contest and an unbiased contest may be fundamentally at odds.

–The Blunt Instrument