interviews

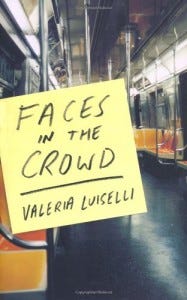

INTERVIEW: Valeria Luiselli, author of Faces in the Crowd

Valeria Luiselli’s debut novel Faces in the Crowd (Coffee House Press, 2014; translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney) is one of those rare books that manages to upend one’s idea of what might be possible in fiction. Masterfully fusing form and content, it is a book that feels compiled, brick-by-brick, a slow accretion of fragments. It is a “vertical,” “simultaneous” novel, told in storeys, like a building to wander through. The soundtrack of the comings-and-goings of the upstairs and downstairs neighbors — past and future — is always superimposed on the present. Yet this narrative, this life, is a wobbly structure, a house “full of holes.” Such a structure can protect, but it can also hide away or destroy. It can be refuge, exile, or death trap. What happens when these walls we erect around ourselves make us invisible or unrecognizable to others? What happens when these walls come crumbling down?

Faces in the Crowd has attracted a number of notable admirers. Enrique Vila-Matas has called this book “the best of all possible debuts…” while Laura Van Den Berg urges everyone to “Read her. Right now.” This year she was named as one of the National Book Foundation’s 5 under 35.

Last week, I met Luiselli at a Greek restaurant near Columbia, where she is currently completing a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature. We talked mostly about the theme of ghostliness in her novel, of hauntings and vertical time.

Anelise Chen: Your novel begins with an epigraph from the Kabbalah: “Beware! If you play at ghosts, you become one.” Why is this novel populated by ghosts?

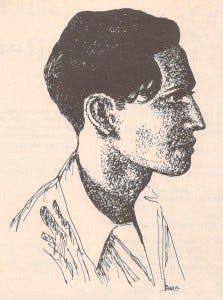

Valeria Luiselli: There were many different levels at which I was trying to explore the theme of ghostliness. The initial seed of the idea came because I wanted to write about the modernist poet Gilberto Owen, the male narrator. He is a ghost inasmuch as he belongs to a literary and social niche that has no clear labels. He was a Mexican poet living in New York during the Harlem Renaissance, but he was always in the periphery, practically unknown. Because he left for America so early in his life, he became a ghostly figure in Mexico as well. So I was interested in talking about a particular group of Latin-American intellectuals, of Mexican writers, who don’t belong entirely to existing cultural or social structures.

Gilberto Owen

AC: Did you initially want to write a story about peripheral literary figures and not specifically about ghosts?

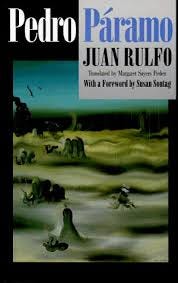

VL: I wasn’t going to frame it as a ghost story. But I was intrigued by the fact that Owen used to weigh himself in the subway every day. He wrote in his journals from the 1920s that indeed he was losing weight, disintegrating, becoming a ghost. Also, when he got older, and got sick from alcoholism, he was gaining weight and growing breasts and becoming blind. He would play with the idea that he was disappearing, instead of becoming blind. The idea of ghostliness came from that character. That, plus the rhythm and experience of ghostliness in the subway. That was the initial intuition that I started following. But I never thought to myself: Write a ghost story. Especially because one of my favorite Mexican writers, Juan Rulfo, is the modern ghost story teller. His novel Pedro Páramo is one of the most brilliant books ever. So it wasn’t at all in my interest to write my own take of his book. I would never have aspired to do it. What is fascinating about Rulfo though, and I reread him when I was writing the novel to figure out how he had done it, is that in one single time frame, he lets the dead and the living coincide. Have conversations. They’re not dead…they’re not even ghosts.

AC: They all seem to inhabit the same membrane of time. I remember in one scene, Owen, almost blind, looks in the mirror and sees Nella Larsen’s reflection instead.

VL: Yeah. Passing. That is a kind of haunting as well. You’re caught between two worlds, neither black or white. Yes. It’s very much a novel about passing too, especially in Gilberto Owen’s story. Of course I was thinking a lot about Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and a bunch of other books and poems and plays I’d read from the Harlem Renaissance, including Lorca’s own poems about Harlem.

But I don’t like to address “issues,” especially not in a novel, not directly. I don’t want to be pedagogical. Fiction is interesting because it enables you to take another route, to say things indirectly, through another channel. Because when I arrived in Harlem in 2008 and lived there for a while, one of the things that was very present to me was the status of Mexicans in the US. I’m speaking about the problematic invisibility of migrants now, which I write about too. But I didn’t want to write a contemporary realist novel about migration and border crossings, so Owen’s story is what allowed me to touch upon those subjects in a way that tends toward ambivalence and complexity.

Nella Larsen

AC: Actually that is another layer of haunting that I hadn’t thought about. Because in the book, you’ve folded time in this really cool way so that past, present, and future are all layered, simultaneous. I was mostly thinking about temporal intrusions and breakages. But in fact there are groups of people we just don’t see, even though we’re all inhabiting the same physical space and time together.

VL: Absolutely, and it’s good that you say that, because there are other instances of present ghostliness. I don’t know if I should label it the “emotional” sphere or what. But I also wanted to explore this problem of building a life that you are not able to inhabit fully. Right? The woman narrator is in that situation, in a way. She’s writing about her past but she’s not there anymore, and she’s not entirely in her present, though her present is very demanding and urgent and there are diapers to be changed and things to be written and a marriage perhaps to be saved. There’s an urgency in the present, but she doesn’t fully inhabit the house that she lives in. She’s a bit of a ghost there too.

AC: Is this inability to be present in the life you’ve made for yourself a consequence of being a woman, a writer, or is this just what happens to everybody?

VL: That’s a good question. I wouldn’t put it in any one category. I don’t think womanhood itself puts you in a position of self-effacement. Of course in certain cultures it’s more predominant. But I don’t think in terms of gender when I write. I think in terms of characters and people and their problems. I don’t even think I think in terms of political problems. These themes of course arise because I’m trying to write about people and their problems, right? But I didn’t think about disappearing as a gender issue in particular.

AC: I’m really curious about the scene where her roommate Dakota is singing into a bucket so she won’t disturb the neighbors, while the husband is working really loudly at his desk. Did you mean for that to set up a sort of contrast?

VL: My mind tends to think in analagous imagery, so it’s likely that it was one of the connections. But it wasn’t deliberate. It wasn’t some statement about women artists having to hide. No, it wasn’t a metaphor. I guess when I wrote this novel I was very much under the influence of imagist poetry: Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams. I was very much in conversation with that when I was writing. I like to think of the novel as a sort of imagist novel, as a succession of images, or an “intellectual and emotional complex,” as Pound used to say. Not metaphors; just images.

AC: So there are literary hauntings too. At one point the woman narrator hallucinates drinking with William Carlos Williams at a bar.

VL: That’s another level of course. Our relationship to books and reading is a dialogue with the dead. Quevedo said literature was a “dialogue with the defunct,” no? Does that even exist in English? It’s a horrible sounding word, defunct. Deceased is probably the right word.

AC: Was that anecdote about Ezra Pound real? Did he really compose “In a Station at the Metro” after seeing a recently defunct friend?

VL: I’ve heard and then read a version of that anecdote. What I wrote is not the entire version that I heard, but it’s very similar to it. But it is true, apparently, that he wrote the poem as a response to having thought he saw a friend of his, recently dead, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. Plus, the experience itself was so fleeting, the poem had to retain that fleetingness. The subway is like that, no? Happily I’m not seeing dead people there all the time but I often see people that I knew long ago.

AC: Owen and the woman narrator haunt each other in the subway also. Why is that?

VL: I think, in the first half, the woman narrator is just starting to prepare the ground for the Owen novel. She is beginning to write Owen into her space so she can actually start writing the novel. What happens is not that Owen’s voice comes in to take over, it’s more like her voice unfolds into his voice.

AC: She’s using him as a medium…

VL: Yes, to tell her own story. I used to draw arcs between each character. I linked Dakota to Garcia Lorca in Owen’s story, Pajarote to Zukofksy. This is sounding like the Wizard of Oz but it’s not. [laughs] I wanted there to be a subtle correspondence between the characters in the two stories. Though Owen is a bit like her husband, no? They have the Philadelphia correspondence, they’re both unfaithful, decadent. Nothing is completely symmetrical. That would be a really boring novel, like a puzzle you have to figure out.

AC: The woman narrator could have just continued telling her story of her own past, but that wasn’t her intent. She wanted to write a story about Owen.

VL: Well, it could be both. Owen was an important presence in her past life, so in order to write about him she has to go back to capture the initial…you know when you find an idea for a novel, you have a moment, like, This is it! Or not! She has to go back, travel back to a moment of connecting to the origins of her emotional attachments to the idea of writing about Owen. Then she can really start to make the story.

AC: Would that be the roof scene?

VL: The roof scene is the moment that reconnects her. After that Owen starts coming in more and more.

AC: And the hauntings extend outward too, to the readers. After I read this book, I became obsessed with ghosts. It described something I was feeling exactly, about feeling not quite present, not dead but not really alive. I started researching, reading books about Victorian ghosts. Then my friend told me about Derrida’s documentary, Ghostdance. It turns out there’s a whole school of thought now called Hauntology. The term comes from Derrida’s Spectres of Marx.

VL: No… I wasn’t aware of any of this.

AC: Right, it was pure coincidence…but anyway it’s this idea about being perpetually nostalgic for the future, mourning the loss of the future. There’s a sense that we’re in no-time. Mark Fisher writes about this in his new book The Ghosts of My Life. “Even loss is lost.” It’s like everything you can imagine happening or existing has always already happened, so you can’t project yourself into any kind of future. And of course nobody can be really mentally present because we’re all on our devices. So anyway, I thought, wow, ghosts. This is really rich stuff…

VL: Yes, I do think ghosts really resonate with our time. Not being able to inhabit your life fully. It’s sort of trite to say, but the velocity of our lives, the emails we answer every day, it’s hard to have a conversation. It’s hard to have bonds and relationships that feel lasting and slow….

Waiter, in Spanish: Can I take this coffee? [As an experiment in tasseography, Valeria has reversed the grounds of her Greek coffee into the saucer to see what it would say.]

VL: No, es para leer el futuro. [Waiter laughs, puts his hands up in surrender, retreats.]

AC: We should have asked him to read the future!

VL: Yes, or we could ask my daughter. She’s very good at interpreting images. [We look back at her…she’s drawing happily at her own table.] Anyway. The fact that you connect to the ghostliness in the novel is telling. I think many people who’ve read this book connect to that very strongly.

AC: It’s like we can’t seem to stop comparing ourselves to ghosts, zombies, monsters. We just feel dead.

VL: I have a friend who’s a brilliant poet. I think he is the most interesting poet writing in Mexico right now. Luis Felipe Fabre. His third book is a kind of critique, particularly of Mexican society, called Poems of Terror and Mystery. Basically it’s all about zombies and monsters or certain poets as monsters and others as zombies. Imitating trash horror. It plays with pop culture, but somehow by using this very common language and these trite concepts, he gets to the core of these very fundamental things.

AC: Yeah, I think so too. Well, now maybe we can talk about this form you’ve created for the book, which seems particularly conducive to hauntings. There are all these holes where past and present can poke through.

VL: The form very much reflects my own mode of proceeding in thought, at least at the time. Not all my books are like that or will be like that I’m sure. In that particular moment of my life, my thought structure was very much in short bursts, pieces, images, fragments if you want. I think the rhythm followed my own rhythm and also the rhythm that I was allowed because my daughter had just been born.

AC: You wrote it after she was born?

VL: No, I started writing it before I was pregnant. My writing experience, at least in two of my books, has been like this: I have an idea, and then I take notes for a long time and I read but then I transition to a period of distance where I just take notes, less intently, and read a lot, but less focused on the novel itself. This is a period of two years, maybe, and in the third year I write intensely for many, many hours a day. I wrote this novel in about nine or ten…or maybe twelve months. Before that there had been twenty-four months of reading and note taking.

AC: I love how the novel feels more architectural than like the prototypical MFA novel, with a catalyzing event, rising action, climax, etc.

VL: [laughs] Does my novel even have a climax? No, I never thought about stuff like that…

AC: But that’s what I love so much about it! When I’m reading I can’t imagine you charting it out in that way. Instead the novel has a mirror structure, a rhetorical structure, prolepsis and analepsis, and it’s also a palimpsest. History gets layered, like a city, it gets built vertically. I guess that relates also to your research in architecture…

VL: I read a lot about urbanism and architecture. I’m interested in ways of articulating space and talking about space. I talk about books in terms of their spatiality. In terms of architecture of space and the way we move inside stories. Spatial analogies come more naturally to me than other types of analogies.

AC: I think that’s what I liked so much about the book was that it felt like I was exploring a building…

VL: It is like that, I guess. I used to be a dancer. I think dance trained me to be very conscious of space and how we relate to it. Dance works like that. Dancers don’t just move around space. They create it, making it visible to the other by moving through it and inhabiting it. That particular consciousness of space is what I try to pull back into my work as a writer.