interviews

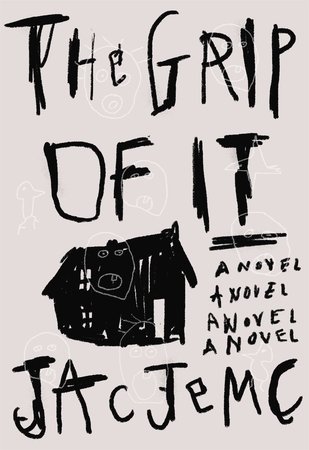

Jac Jemc Thinks Romance is a Little Paranormal

The author of ‘The Grip of It’ discusses the many ways a house and a marriage can be haunted

I n the sprawling neighborhood of American literature, a significant proportion of the houses seem to be haunted. Given that the metaphorical figures of ghost and house are both about as loaded as they come, it’s no surprise that heavy hitters from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Henry James to Toni Morrison have employed the device for their own storytelling purposes, and its possibilities remain far from played out. Ghosts — i.e. entities trapped in temporal loops by some trauma — are a great way to throw a wrench into standard narrative assumptions of forward motion; they’re also perfect analogues for all manner of anxieties and compulsions, from the psychological to the historical. And a fictional house is apt to serve as a ready metaphor for an individual psyche, or a family, or a milieu … or, for that matter, for the literary work itself.

Jac Jemc’s second novel The Grip of It is a distinguished contribution to this creepy catalogue, partaking of the full richness of the tradition while extending the franchise through fresh moves of its own. Her haunted house — the fabulously-named 895 Stillwater Lane — is the new home of a young couple who’ve left the city to seek a fresh start in a small town, and swiftly emerges as a harrowing analogue for their marriage, with hidden passages and unquiet presences paralleling secrets they’ve concealed from each other and themselves. As Emily Dickinson cautions, “One need not be a Chamber — to be Haunted — / One need not be a House — / The Brain has Corridors — surpassing / Material Place.” Although the opening pages of The Grip of It neatly insinuate ghostly meddling, as the novel grows more fraught and claustrophobic, the prospect of an overtly supernatural antagonist begins to seem less like a menace than a relief. Just as an exchange of vows marks the end of many a classic romance, the cosigning of a mortgage turns out to be a hell of a way to kick off a horror story.

Jac Jemc’s first novel, My Only Wife, won the Paula Anderson Book Award and was a finalist for the PEN / Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction; she is also the author of a short story collection (A Different Bed Every Time) and a chapbook of prose (These Strangers She’d Invited In). Her last name is pronounced “jems.” Although we both live in Chicago, and should probably hang out more, we conducted this conversation by email in August of 2017.

Martin Seay: A reader first encounters The Grip of It as a haunted-house story — which it certainly is, though it quickly reveals itself to be other things, too: a story about marriage, and about trust. In an essay called “The Shadow Chamber, The Boarding House, The Grip of It,” you also mention that some of the novel’s creepy twists and turns are inspired by the work of South African photographer Roger Ballen. I’m always interested to learn about the initial spark of a novel. Do you recall what The Grip of It was first, before it really began to take shape? Where did it begin?

Jac Jemc: The initial spark was simply: I want to write a haunted house story that doesn’t limit itself to the physical boundaries of the house. The initial working title for the book was The House, the Woods, the Water, but then Matt Bell announced he was publishing a fantastic book called In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods, and I thought, “Welllll, great,” and had to change the title, but the idea of the haunting expanding to the natural world (both the nature surrounding the house and characters’ bodies) was there from the start. It wasn’t until much later that I realized I was really writing about a relationship again (which was also the focus of my first novel, My Only Wife). There’s something impossible to me about romantic/domestic relationships that I keep returning to — about the assumption that they’ll be a part of everyone’s narrative, about the ways we discuss the magic that supposedly guides them. There are moments when I can give myself over to the idea of romance, but there are more moments when I just can’t stop laughing at how absurd and embarrassing and lonely it really is. At some point I realized that writing about a haunting had brought me full-circle back to that idea.

There are moments when I can give myself over to the idea of romance, but there are more moments when I just can’t stop laughing at how absurd and embarrassing and lonely it really is.

I think I wanted to write a haunted house story because I love them and somehow it hadn’t occurred to me that I could participate in the creation of this thing I love. As a writer, I really move pretty blindly through what it is I like to write and plan to write. I’m sure I like haunted houses because I like thinking about the relationships between people and the ways that we can distrust those we’re closest to, including ourselves, but that’s not something that I could have identified before working on this book. The idea for the house came first, and all of the fissures between characters showed up much later. It’s not unusual for me to work in such a spontaneous way. I’ll often start with an image or a phrase, and grow the idea from there, without much more thought or planning. I wouldn’t say I’m even a particularly savvy reader of my own work, at least in the early stages. I trust my instincts and then eventually my motives begin to come clear, but it takes time.

MS: The Grip of It is the story of a young married couple who seek a fresh start by buying an old house in a small town; stuff gets weird right off the bat, and keeps getting weirder. The story is told in the first person, from the mostly-alternating perspectives of the couple, Julie and James. Something that struck me right away was their voices, which are convincing and distinct, but not exactly naturalistic: Their language is often expressive, figurative, oblique, and very much not designed to set up a baseline normalcy that’ll be disrupted by the supernatural later in the book. Since we have no access to any external point of view, we’re never sure how much we can trust our two narrators, a circumstance that resonates throughout the novel with unsettling force. It’s a bold move on your part, and kind of brilliant, I think. Can you say a little about how you developed the characters’ voices, and what the considerations were?

JJ: Well, the short answer is: figurative, oblique language is my jam. It’s what keeps me mashed to the page and working. At the time of drafting the book, that style of language was what was driving my writing, and so I sought a project that would match that obsession well. With revision, I tried to add more language and plot that was easier to grasp and I tried to restructure the book so that the haunting does feel as though it’s ramping up. In earlier drafts the language started and remained dense, without much everyday life/dialogue to anchor it, even flimsily, to the real world. There was also a third narrator, the neighbor Rolf, whose language was the dreamiest of the three of them, a spectral swirl that the reader was forced to slog through to try to figure out what was going on. Eventually he had to be cut and the information he shared had to be delivered in a more straightforward way to James and Julie, rather than to the reader. I was slow to figure out that balance. I also tried, over time, to pull apart James and Julie’s voices — the rhythms and what they talk about and how — but many similarities remain between them, as a nod to the way couples start to use the same expressions and tell each other’s stories and develop the same interests.

MS: I totally bought Julie’s and James’s narration, initially despite and later because of its peculiarity. I should mention that Grip also features some great minor characters — Julie’s down-to-earth colleague Connie, some just-the-facts police officers — who serve as smart and effective counterweights to all the strangeness.

When I was trying to figure out how to describe the narration in Grip, a word that I kept picking up and discarding was “poetic” — lame, I know, but maybe worth using in a specific sense here. What I mostly mean is that poetry (open-form poetry, anyway) strikes me as the literary form that a reader encounters with the least certainty about what its rules are supposed to be … whereas genre narratives like horror stories are largely defined by how they navigate rules and conventions. It seems like it shouldn’t be possible to use the rhetoric of poetry in a horror novel, but I think you do it really effectively in Grip. You’re a poet as well as a writer of novels and stories, and a lot of your work in each of those forms seems to operate in the unmarked territory that lies between them. How important were such formal considerations when you started writing The Grip of It? Its chapters are all quite brief, and some function almost like flash fictions; did the book always work that way, or did that approach emerge gradually?

JJ: I didn’t pay much attention to the rules and conventions of horror novels as I was writing. I’ve read a lot of horror stories, but not an impressive number of horror novels. The short chapters are a product of my own short attention span: usually, on a regular weekday, I try to write about a thousand words, so the chapters you see were probably each written in about a day, and then revision offered the opportunity to cut them down or expand them or mix them up. The short format of the chapters let me convince myself that I could work in a similar way to how I had been writing stories at the time, but instead of wrapping up the end of a story, I had to provide a launchpad into the next chapter. The language was always crucial because much of the haunting is suggested by the uncanny way James or Julie formulate something familiar with their words. Something normal is happening, but the reader knows that the character is experiencing it as strange because the words they’re using to describe that thing are off-kilter.

I didn’t pay much attention to the rules and conventions of horror novels as I was writing.

MS: Although The Grip of It is a fairly unconventional horror story, I appreciated the way it subtly acknowledges its forebears without ever imitating them. I thought I spotted quick nods to all sorts of scary predecessors — from Poe to Paranormal Activity — but in other interviews you’ve made particular mention of Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle and Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves as inspirations, or at least as favorites of yours. Some similarities aren’t hard to spot — like Jackson’s, the horror in Grip is psychological, human-scaled, and uncanny, without exactly being weird in the Lovecraftian sense; like House of Leaves, Grip is a story about a marriage, set in a spatially confounding house — but do you mind saying a little more about what you admire in these two novels, and how they were helpful with respect to Grip?

JJ: I admire House of Leaves for its willingness to be big and messy and for the fact that it was truly the scariest book I’d read. I am hard to creep out and that book did it. That said, I read it when I was 22 and I haven’t really returned to it (I wish I was better about rereading) so any influences are probably pretty distorted at this point. We Have Always Lived in the Castle was helpful in the way it allowed me think about what information gets shared when, how familial secrets drive the unease in the reader and keep them moving forward. I looked to that book for help with structure, but only after I’d amassed the raw material of my rough draft. I do love Edgar Allan Poe. “The Fall of the House of Usher” and the way it physicalizes the relationships in that book was in the back of my mind. And I did see Paranormal Activity — in the theater! I never see movies at the theater so the fact that I dragged my partner out to see that seems especially surprising to me looking back. I can’t say I loved the movie, but I do viscerally remember the way that people move in the surveillance videos, and what a clear indication of strangeness the movement represented. You’ve got a good eye! With much of my writing, it seems that I find inspiration in work that is quite different from my own; the connections seem really intuitive and clear in my head, but they’re often hard for me to articulate.

MS: You don’t have to answer this, but…about a hundred years ago I read a Bill Flanagan piece in Musician in which he talked about hints that songwriters sometimes drop to suggest that something they’ve written is about them personally. (His example was Springsteen in “Dancing in the Dark,” singing about how he gets up in the evening and comes home in the morning — regular business hours for a rock musician, but not for many other folks.) To be sure, In the Grip of It contains numerous clear indications that it is, like, super-duper-fictional … but am I nuts to also detect clues that it’s also rather specifically personal? I mean, you’ve dedicated Grip to your very awesome partner Jared — and the two of you conspicuously share first initials with your novel’s protagonist couple. Jared took the great author photo that’s on your book jacket; in the novel, James is a serious amateur photographer. Stuff like that. Am I — to use a classic ghost-story cliché — seeing something that’s not there? If I’m not mistaken about these glimmers of personal parallels, are they traces of your engagement with the material, or are they another hook to draw the reader in? Or both?

JJ: Ha. That is pure messiness on my part. I didn’t even think about the initials until after the book was finalized because I stole the names from some former coworkers and I was so worried they’d think I was saying something untoward about their relationship. The names had just been placeholders and then I became attached to their music (as it seems happens a lot from other writers I talk to). I can call out a few things that are not dissimilar to me and Jared: I always want Jared to get a haircut. I’m the more Type A between the two of us. Jared does video work and so he can handle a still camera pretty well, too. There’s more that’s pretty far away from us though: Jared does not have a gambling problem (though I have seen him genuinely enjoy a slot machine for an extended period of time that seemed mysterious to me) and he doesn’t like plants or nature. We’ve never moved a distance together to start over. Neither of us has ever seen a ghost and I don’t think I believe in them. I haven’t queried Jared on his feelings about ghosts too closely (though there is a really great Jincy Willett story called “The Haunting of the Lingards” about a couple and how their differing feelings about ghosts tears their marriage apart, so maybe I should).

MS: I am glad to get that on the record! I should probably say that I never felt as though Grip was disclosing anything specific about your life or your relationship — the particularizing details all seem invented — but I did get the strong sense that your visceral depiction of the struggle to maintain trust in the face of inevitable disappointment, confusion, and doubt is deeply felt, and carefully rendered in a way that I think will prompt uncomfortable recognition from any adult person who’s ever been half of a couple. (The fights in the book, for instance, are fantastic. The fact that they may be driven by some malevolent, identity-corroding supernatural force makes them seem more realistic rather than less so.)

JJ: Ah, yes. I think this is a fair assumption! I see what you’re saying. I have a few responses: 1) A fight scene is going to be informed by the way I fight or the way I’ve closely watched other people fight. 2) Jared and I really don’t argue much. It’s a pretty chill environment in the Jemc–Larson household. We nag each other about different things, but there’s a foundational trust that is quite different from the cracked ground on which Julie and James stand. That said, the urge to nag, my desire for Jared to know when the floor needs to be swept rather than my having to ask him to do it, is real and present enough that I can map that feeling onto a larger issue like a gambling problem, and how Julie needs to recognize that her commitment to James means that she is committed to supporting him through another instance of that (or a different) failure. I do think people can change, but I think that work is very slow and unreliable, and so you make your peace with the few imperfections, but that doesn’t mean you stop noticing them. And hopefully you’ve picked a person whose positives far outweigh the negatives for you. 3) There are things about the fights that I might be able to trace back to my parents more than James and Julie. My parents (neither of them will read this, but, Mom and Dad, please forgive me if someone brings it to your attention) fought a lot, and one of the people in the pair was not reasonable in their methods. (I’m trying to be generous.) Logic would flip-flop with such dexterity that I remember listening from my room, rapt, at both the one’s ability to fight so ruthlessly and the other’s to take the blows and try to force rationality into the situation. They love each other and have been together for 47 years, but I remain kind of astonished that two people with such different relationships to reason could remain so closely tied for so long. I try to avoid direct personal parallels, but some tie to my real emotions is always there.

Rejection is constant. Don’t let it deter you. It’s a lesson we need to keep reminding ourselves of, and a particularly hard lesson for some to learn when they’re starting out.

MS: To step away from the book for a moment … for a long time now, you have been faithfully blogging your rejections: When a publication or publisher turns down something that you’ve sent them, you record it on the internet, sometimes with a little detail about the particulars of the response and what (if anything) you think it might portend for whatever you’re submitting. (As of July 24, 2017, you’d blogged 374 rejections.) Years ago, when I first learned that you do this, I probably raised an eyebrow, assuming that this process was some kind of public self-flagellation. That was dumb of me. I have since come to understand the blog to be an outstanding resource for other writers — not in the usual sense that it provides information about markets and strategies or whatever, but in the more valuable sense that it demystifies the process of sending out work, it models professionalism and persistence and other good practices, it provides great examples of how to read one’s own writing in light of editor feedback, and, maybe best of all, it connects your labors as an independent writer to an entire community of people who are working hard to succeed at something they love. How long have you been doing this? Has your process changed over the years? As your writing has been published more and more widely and prominently, have your feelings about it changed?

JJ: I think it is a public self-flagellation though! You wouldn’t have been wrong. It’s something I constantly think about cutting off because I think it’s only getting more embarrassing with time, but apparently I like being embarrassed? It’s a way of atoning for all of the obnoxious self-promotion of social media, and I think that was a dynamic I was cognizant of from the start. Even in the beginning, if I met a friend for a drink, it felt easier to tell them I’d gotten a rejection letter than to tell them I’d had a story accepted. The latter felt braggadocious. Social media makes it so easy to brag, but I still don’t feel good about it. Right now, three weeks after the book has come out, I feel about ready to crawl into a hole because I’m so tired of talking about myself. That said, I do enjoy the spot of attention because it fills me up and helps give me confidence for the next thing, but I don’t have the stamina built up. I find myself ready to retreat and start ticking off the failures again pretty quickly. I’ve been keeping the blog for close to ten years. My process has remained pretty much the same, though I’m sure I’ve missed a few things out of sheer laziness. I am really bolstered, though, by the number of people who find it helpful. Rejection is constant. Don’t let it deter you. It’s a lesson we need to keep reminding ourselves of, and a particularly hard lesson for some to learn when they’re starting out.

MS: One last thing: What’s next for you? Mad King Ludwig, I hear?

JJ: And, yes, a novel about the Mad King: still plenty of ghosts and faulty architectures and interpersonal misses, but now with royalty and some nods toward our current political situation.