Craft

Like Anne Rice, I Wanted To Pursue My Own Strangeness, Darkness, and Power

How the Queen of Gothic lit gave Lisa Locascio Nighthawk a career roadmap, and insight about her mother

I get ready in front of the big mirror in the front, taking the black crushed velvet cloak from where it hangs between my mother’s fur coats and sweeping it over my black jeans and black t-shirt, fastening it under my chin, pulling up the hood. I set the fangs inside my mouth, feeling the familiar sensation of plastic against my gums and molars. With the tube of fake blood I always keep in my pocket, I draw two stripes beneath my lower lip, each extending from the approximate location of a top fang. I smudge the blood to make it more real.

My dad appears behind me in the mirror. “Ready?”

I follow him through the kitchen, cloak dragging on the tile as I gather a stack of thick hardcover books from the counter, and out to the gray Saab. We drive to the shopping development on the edge of our town with a Walgreen’s, a Coconuts Music & Movies, a Boston Chicken, and a Super Crown bookstore.

It is August 29, 1996, and Anne Rice is signing books in celebration of the release of her latest novel. The line extends out the door of the Super Crown, under the El tracks, and around the corner. We make our way to the end of the line, but almost as soon as we take the last spot, a woman in a Super Crown polo approaches and tells us to follow her. Because I am eleven years old and dressed like a vampire, we get to cut the line. Inside the store, we approach Rice, who wears a frilly white shirt and her trademark blunt salt-and-pepper bangs. She smiles at me and tells me she likes my costume—”Nobody else dressed up tonight!”—as she reaches for our pile of books. Her signature costs $6 per book, $20 for the one we have her personalize to my mom, who is also named Anne. My mother is Rice’s great admirer, the reason my dad and I are fans, but she doesn’t come with us to Super Crown.

To Anne, Anne Rice writes. Anne Rice.

When Anne Rice dies twenty-five years later, I will want to ask my mom why she didn’t come. How did she discover Anne Rice’s work? What about it so captivated her? Why did she make it such a big part of my childhood? And what is the connection between her, Anne Rice, and my career as a novelist? But I can’t, because when Anne Rice dies, my mother will be dead, too—for almost two years.

An obvious connection is that both Anne Rice and my mother had difficult, traumatic, peripatetic childhoods spent partially in Texas. It could be said that Rice’s incredible literary success—150 million copies of her books have been sold—was the product of transmuted grief. In childhood, Rice suffered first the death of her grandmother, the stabilizing force in a household rocked by her mother’s alcoholism, and then she lost her mother, too. After that, Rice and her sisters were placed by their father in a Catholic boarding school that Rice later described as “something out of Jane Eyre.” At twenty-one, Rice married the poet Stan Rice, and had a daughter, Michele, who died of leukemia at five years old. Her first novel Interview with the Vampire was written in the wake of all of these losses.

Elements of Rice’s biography—being raised by loving grandparents and then losing them, neglectful parents, being sent off to Catholic boarding school—line up uncannily with my mother’s childhood. But that alone can’t explain the link my mother felt to Rice’s work. After all, Rice’s vampires entranced millions and millions of readers.

Interview with the Vampire came out in 1976, well before the vampire renaissance: before Lost Boys, before Buffy, before Twilight, before True Blood, before The Vampire Diaries, before Underworld and What We Do in the Shadows and Let The Right One In and A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night and Vampire Academy. Or perhaps it’s better to say that Rice’s vampires inaugurated the vampire renaissance. Before Rice, vampires were popularly understood to be Nosferatu-style monsters whose sexual charisma, if it was depicted at all, wasn’t seductive but instead was horrifying, explicitly connected to fears of rape and murder. Only Dark Shadows, the intergenerational vampire family soap opera that orbited the tortured Barnabus Collins and ran on ABC from 1966 to 1971, heralded an elegantly anguished vampire at war with his elemental nature and on an existential quest for meaning. (It was also my father’s favorite childhood television show.)

Before Rice, vampires were popularly understood to be Nosferatu-style monsters whose sexual charisma wasn’t seductive but instead was horrifying.

Rice said that she drew her inspiration from an earlier source, the 1936 film Dracula’s Daughter, when she created the tortured creole vampire Louis de Pointe du Lac, his Gothic love affair with his blond French maker Lestat de Lioncourt (Rice’s most famous character—my mother loved Lestat; all her life she had a taste for beautiful, foppish men), and Claudia, the five-year-old girl who Lestat turns into a vampire in an attempt to cheer Louis up.

In Claudia, Rice created a child with the complexity of an adult, a being who lived a whole Grand Guignol in a small body—a child who had the extraordinary story Rice’s daughter was denied, or perhaps the extraordinary life Rice observed in Michele’s short existence. Claudia dies twice in the arms of her mother: first when she is first bitten by Louis while clutching the corpse of her human mother who has died from plague, and again when the sun burns her to death as she is embraced by the vampire mother she has demanded Louis make for her.

In Our Vampires, Ourselves, Nina Auerbach writes that “Claudia is an adult male construction, a stunted woman with no identity apart from the obsessions of the fatherly lovers who made her.” But I don’t think Claudia is made by men at all. She is a little girl made immortal by her longing for her mother—the bottomless hunger from which she derives her dark power—and created by a mother longing for her own lost daughter.

I first saw the film version of Interview with the Vampire when I was myself a little girl. I was curious to watch the movie my parents had so enjoyed. My mother showed me the movie in the manner she screened many films deemed inappropriate for children that she nonetheless wanted to show me: by starting and stopping the videotape, telling me to look away while she fast-forwarded to the next scene she wanted to show me. Sometimes this style of watching annoyed me, and sometimes it made me uncomfortable, but I never looked away. I always saw what my mother wanted me to see. I don’t remember liking or disliking the movie, but I remember the feeling of being so close to my mother, so deep in her world and mind and pleasure. I always loved being with her, even when I had trouble figuring out where she ended and I began. Togetherness with her was, and remains, the thing I wanted most in the world. It was automatic for me to emulate her tastes. I’m not sure it was even emulation so much as a kind of osmosis. Transfusion.

I don’t remember liking or disliking the movie, but I remember the feeling of being so close to my mother, so deep in her world and mind and pleasure.

I had my first experience with a vampire during another of these movie screenings. I was seven years old and my mom showed me a vampire movie from the 1970s with a heavy, innuendo-laden atmosphere. I fell asleep in her bed, but I didn’t rest. All night I was in and out of dreams of ravishment and fangs. I couldn’t escape. By morning I didn’t want to. After that it was automatic. Of course I loved vampires.

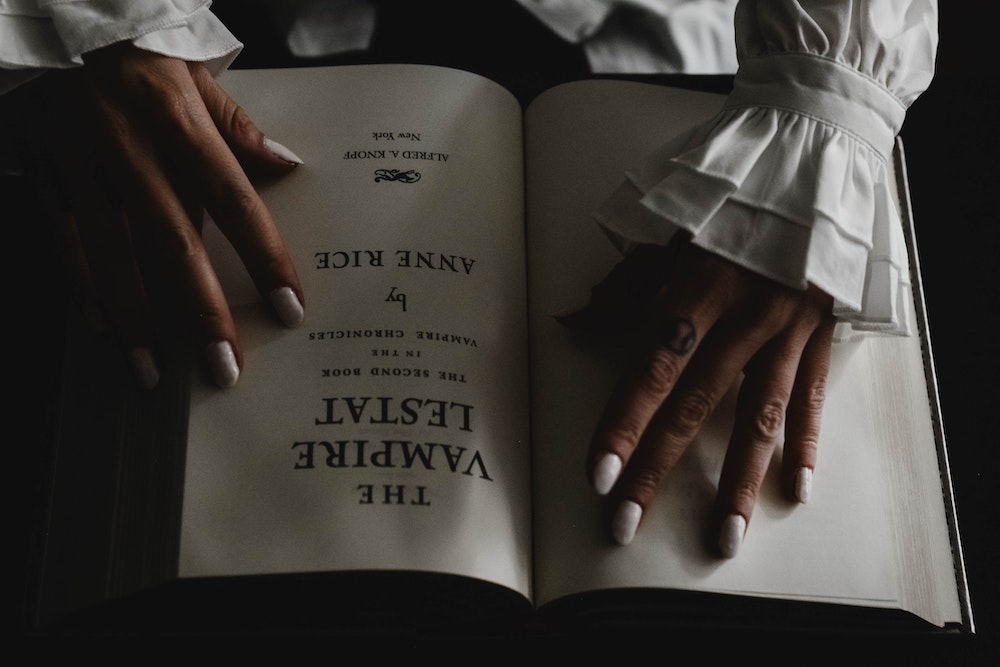

In a video assembled by the Associated Press in remembrance of Anne Rice following her death, there is a shot of the long, shiny, chrome tour bus she traveled in the summer I met her. I’ve attended hundreds of book signings and readings in the years since the night I met Anne Rice at Super Crown, including my own book tour following the release of my first novel, but I’ve never again experienced anything like the crowd, excitement, and money that she drew that evening. In the video clip, her tour bus is emblazoned with the words “ANNE RICE SERVANT OF THE BONES 1996 INTERSTATE BUS TOUR.” We bought a copy of Servant of the Bones that night—it was required for entry, and it was the one we had Rice sign to my mother—but I never read it. In fact, although my parents both loved Rice and read many of her books together, I only ever read one, a paperback of The Vampire Lestat that I received in a Secret Santa years later.

Rice wasn’t my favorite author. She wasn’t even my favorite vampire author. That honor belonged to Poppy Z. Bright, whose work I discovered on the other side of puberty. But I think she was my originating idea of the author: a powerful and mysterious woman. Even without reading it, I knew that her work was dark and sexy and infused with the supernatural. It was also, both in the culture of my home and in the wider world, indisputably important. She was a far more interesting and accessible model of the writer than Ernest Hemingway, the hometown hero whose grizzled, black and white image decorated the walls of my favorite restaurant. It was from Anne Rice that I gained my sense of what writers were, of what a writing life could be.

I decided to be a writer when I was very young, for the simple reason that I was good at writing and enjoyed doing it.

I decided to be a writer when I was very young, for the simple reason that I was good at writing and enjoyed doing it. I read constantly, anything I could put my hands on, and I thought that the world was full of people like me, who adored books and considered their creation the highest and most important work. It wasn’t until I was an adult that I learned that the literary establishment looked down on horror, science fiction, fantasy, and comic books—the genres that my parents introduced me to, and that I most enjoyed reading. I didn’t know that there was a literary establishment that didn’t include Anne Rice.

Over the years of writing my first novel while supporting myself with a PhD stipend, a patchwork quilt of adjunct teaching jobs, and the occasional freelance assignment, I was haunted by the image of the writer I met that evening at the Super Crown: a woman behind a laminated folding table, receiving supplicants like a queen. I would think back to the way her supersized hardcovers asserted themselves on our bookcases, their shining gold and black dust jackets, their unquestionable importance. The idea of Rice made it seem not just possible but obvious that I would make a life telling stories, regardless of the pushback I might receive. This sense of artistic mission has sustained me through many low points.

But often, at those low points, I resent this innocent, grandiose idea for leading me into a line of work that, I have been surprised to discover, is neither glamorous, well compensated, or even interesting to most people. Did I become a writer for art’s sake? Or did I get myself into this mess because I thought that my career would be like Rice’s?

In a 2018 interview with Locus, the author and screenwriter Tananarive Due describes how, as a young journalist struggling with her desire to write fiction about the supernatural despite the disapproval her interest in writing genre elicited from peers and professors during her education at Northwestern University, she was assigned to interview Anne Rice.

I never told [Rice] I was a writer. I just slipped it in with my questions, like they teach you in journalism 101. “How do you respond to criticism that you’re wasting your talents writing about vampires?” I cringed and waited for her to answer. She just laughed. I think she literally laughed. She said, “That used to bother me. But my books are taught in colleges.” She went on about how freeing it is to write genre, and the way that big themes can play out in genre in ways that are harder to get away with in contemporary realism and smaller stories. She lit a fire under me. […] The interview was literally a pep talk, even though Rice didn’t know it.

Rice was an idiosyncratic figure: a serious, cerebral writer whose contemplative, over-the-top Gothic novels took genre mainstream. Her popularity defied the high-low paradigm and expanded what was possible for writers. Pursuing your own strangeness, darkness, and power, Rice’s career showed, could help writers tell stories millions were dying to hear. In its remembrance of Rice on Instagram, the literary agency Janklow & Nesbit (whose founder, Lynn Nesbit, was Rice’s longtime agent) remarked on the fact that Rice’s books “importantly, at the start of the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s—allowed space for eroticism and sexual pleasure across straight and queer characters.” Many have followed in her wake, not least of all her son Christopher Rice, who himself writes supernatural, crime, thriller, and romance fiction.

Pursuing your own strangeness, darkness, and power, Rice’s career showed, could help writers tell stories millions were dying to hear.

The writer could be not just known but a star, and not just a star but an ideologue, a beacon of tolerance and openness, a glamorous—and for much of her career, fat—woman with a sense of humor and an unabashed appetite for sex and gore who understood her books to be novels of ideas and philosophy, concerned with the great questions of history. “My private life, my private adventures,” Rice said in a 1996 interview with her friend Michael Riley, “really are in this realm, sitting at home on the floor, cross-legged with books, trying to figure out why the Roman Empire fell.”

Maybe my mom didn’t come to the book signing because of her dislike of crowds. She often stayed at home, in the house she had decorated, where nearly every room bore a Rice book or two, while my father and sister and I went out into the world. But in the same way that Rice’s fans felt that she transformed their imaginations, my family understood that to be close to my mother was to gain entry to a world of magic and fortune where the impossible became real and dreams came true. We brought everything home to her, cast our spoils before her, waited for her to tell us what they meant.

“Look at Anne Rice,” my parents said, encouraging me to pursue my love of writing and, implicitly, suggesting that I could make a career of it. Both of them believed I had talent. Both read my writing and saw beauty and meaning in it. They made the sacrifices other families make for grueling sports schedules so that I could attend weekend writing workshops, pursue literary internships, and complete multiple graduate degrees.

From the beginning my writing was always about my obsessions, which included big moods, secrets, sex, and, yes, vampires. As I kept writing, a strange thing started to happen: as much as I wanted to write about magic and the supernatural, the worlds I evoked became stranger, surreal, propped between our world and others, concerned with labyrinthine and internecine interior landscapes, as a hidden order made visible. Like Anne Rice, I became a writer, but different, writing my own kind of stories, about my own kind of supernatural occurrences and ecstatic revelations.

Like Anne Rice, I became a writer, but different, writing my own kind of stories.

There is a ligamentous connection between my two Annes and my own writing. I find myself wanting to articulate the impact they had on me, how they made me a writer through the act of exposure, through the things they showed me, the way they encouraged my artistic reaction. I keep coming back to Rice’s definition of romanticism as “an abandonment to the realm of senses and feeling where you don’t restrain yourself, there’s nothing ironic or cynical holding you back in your art. You give totally.”

Her words describe not just Rice’s books but also the way my mother lived and taught me to live in the world. With the help of the example of her favorite author, my mother gave me permission and encouragement to live—and write—with generosity and sincerity and open-heartedness. She gifted me the freedom to follow Anne Rice, who said that to write well, all you have to do is “let the blood gush.” My mother taught me to smudge it, to make it more real.