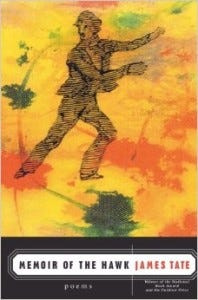

Books & Culture

MEDIA FRANKENSTEIN: Fundamentally Unreliable

THE HEAD: The Debt to Pleasure: A Novel by John Lanchester (2001)

“What is its artifact-iness?” a teacher once asked me about a wild and grandiose dystopian science fiction story I had written in the process of obtaining my MFA, a question which has lingered in my mind ever since as both a reader and a writer. The story masqueraded as the written confession of a schlubby gunner pilot from World War III (really, a retro take on WWI) who, after bringing about a coup when he accidentally shoots down a superstar rival, gets touted as a hero — so on and so forth, insert conceit here. The story didn’t really work. It had gestured at being its own artifact, a thing that transcended the world of the story yet was, at the same time, innate to that world — for examples, see Charles Kimbote’s annotations of John Shade’s poem from Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1962), Briony Tallis’ novel from Ian McEwan’s Atonement (2003) or, more recently, David Bellen’s titular essay from Zachary Lazar’s I Pity the Poor Immigrant (2014) among many others — but for whatever reason had failed to do that — hadn’t made itself over as actually there. “This is not a conventional cookbook,” says Tarquin Winot at the beginning of John Lanchester’s The Debt to Pleasure. “Though… I have nothing but the highest regard for the traditional collection of recipes… The omission of a single world or a single instruction can inflict a humiliating fiasco on the unsuspecting home cook.” Tarquin, the dandified, grandstanding and highly amusing narrator of The Debt to Pleasure goes on to enumerate such an episode of “omission” from his own life in which his brother Hugh forgot to pluck a pheasant before roasting it only to extract the thing from the oven hours later, “terrible in its hot sarcophagus of feathers.” The prose style and narrative devices on display in this opening passage are more or less representative of the rest of the novel. The high-flown and arch Nabokovian rhetoric, the more-than-a-little-bit-sinister humor, the textual trail of breadcrumbs being laid, the unreliability, writ large and in charge. Tarquin’s “omission[s]” over the course of the novel function in a double sense. On the one hand, of course, because Tarquin lies and attempts to bedazzle and mislead the reader and because, on the other, the novel is more; it takes shape as an artifact deriving from itself. The New Yorker called The Debt to Pleasure “a novel masquerading as an essay masquerading as a cookbook [that] somehow manages to combine the virtues of all three,” and in that assessment it wasn’t far off. It has the pleasantly dithering and indirect aspect of a hybrid form. Tarquin — real name Rodney — a Humbertian aesthete, narrates the story en route from Portsmouth, England to his house in the south of France. Oh, and by the way, as Tarquin would probably reveal it, he’s traveling in disguise, his hair buzzed, his glasses tinted, dogged by the none-too-distant deaths of his parents (gas canister accident), family cook (Tube-train accident), nanny (suicide accident) and of his bumbling and undeservedly famous brother Hugh (poisoning accident), a multimedia artist, whose posthumous biographer Laura Tavistock, it emerges ere long, Tarquin has been shadowing on her honeymoon through France. Tarquin is a sociopathic murderer, not to belabor the obvious, yet the novel’s pleasures lie less in discovering that fact (which you come to suspect early on) and more in experiencing at close range his high erudition, his (or Lanchester’s, rather) satirical skewering of New-York-Times-Magazine-esque epicureanism, his vain, delectable phrasing (“There is an erotics of dislike…To like something is to succumb, in a small but contentful way, to death.”), his disarmingly naïve hope that he is hiding from the reader. The Debt to Pleasure is not the first novel to enact double unreliability, but a superlative example all the same: on one level, it pits the reader in a game of wits with the narrator, taking out high stakes bets on who will crack first; on the other, it does the same between the reader and the author. What manner of man am I, really? asks Tarquin, never mind we know already. While Lanchester asks us the trickier question: What manner of book do you hold in your hands?

THE TORSO: Swimming Pool dir. Francois Ozon (2003)

In the film Swimming Pool, also set in England and the south of France and also filtered through a questionable narrator with a criminal turn of mind, the unreliability is much more overt. The first scene has mystery author Sarah Morton (played with steely reserve by Charlotte Rampling) riding the Tube through London when a fellow passenger, engaged in one of her novels, recognizes her from the dust jacket. “You must’ve mistaken me with someone else,” Morton says. “I’m not the person you think I am.” Thus does Morton, author of the bestselling Inspector Dalwell-series, establish herself as fundamentally unreliable early on in the plot. Here is how that plot goes down: Morton, suffering from writer’s block, travels to her editor’s and presumably former lover’s (Charles Dance) country house in the south of France in the hope that it will help jumpstart her next installment in the Inspector Dalwell-series, his cash-cow, Morton’s albatross. No sooner has Morton arrived on the property and fallen into a rhythm of ascetic creativity than the editor’s French floozy of a daughter (Ludivine Sagnier) blows onto the scene, interrupting Morton’s writing with loud TV-watching, audacious sunbathing and drunken sex with a series of progressively more unappealing local men. As might be expected, the women turn out to be uncomplimentary foils for each other. A comical tension develops between them (“Okay, I’ll leave you alone, Mrs. Marple,” says Sagnier to Rampling. “I need to make some phone calls anyway.”), followed by a grudging friendship. There are little reminders afoot, in the meanwhile, that the mystery writer is not to be trusted: she’s struggling with drinking, she’s having hot flashes (not that menopausal women are master deceivers but only that Morton’s perception is skewed), she develops a not-quite-platonic obsession with Sagnier’s incontestably sexy Julie, fantasizing about her, recording her habits, abandoning her Dalwell-novel for a file on her laptop she titles “Julie.” Yet just when you think that Swimming Pool is going to veer into Notes on a Scandal (2006) territory — another wonderful English psychological thriller of obsession centered around chronologically disparate female leads (Cate Blanchett and Judi Dench) — it throws you for a quirky loop. It’s a credit to Francois Ozon that he foreshadows this plot twist (which I’m here going to spoil) through swirling Hitchcokian mis-en-scene: the titular swimming pool on Morton’s editor’s estate slowly revealing itself beneath a retreating carpet of surface scum; Morton typing at her desk in front of a mirror opposite another mirror where an uncanny long-view of Mortons sit, typing. After Morton becomes Julie’s accomplice in the murder of a local man who rejects her advances and Morton travels back to England to deliver whatever she’s been working on to her editor, we see that the name of the book she has written is also the name of the film we’ve been watching. Julie doesn’t turn out to be Julie at all; there is a Julie, she just isn’t Sagnier. Swimming Pool is, finally, a crime story without the crime. It’s a drama masquerading as a murder-mystery story masquerading as a story of imaginative process (Secret Window, Adaptation). Indeed the film’s depiction of this process is so literal — Morton’s mind to our eyes — and yet so indirect — red herrings of murder, wild sex and obsession — you may wonder at first: so what? But the film is so insistent on this simple conceit that a spare elegance ripples out from the credits. Like Lanchester’s novel in so many ways, it’s aware of itself as its own artifact, a literary movie that is actually a novel, and yet it’s difficult to tell where the novel begins and the frame-story ends. Herein lies its subtle power. By taking something make-believe and making it into a tangible object that exists as a part of a fictional world, Swimming Pool is somehow able to abstract itself from the thing that it is.

THE LEGS: Memoir of the Hawk: Poems by James Tate (2002)

The many speakers in James Tate’s thirteenth collection of poetry, Memoir of the Hawk, partake of a brand of unreliability that is less innate to their psyches individually than to the world they inhabit. In this world, dubious mama’s boys open flower shops called Murder, Inc., alien-wives made of metal terrorize the human population, towns develop addictions to super-abundances of coffee and rider-less donkeys cart coffins to the ends of the earth. None of this is atypical, of course, when it comes to Tate’s career-long gambit to establish his own brand of bemused, melancholy surrealism. In Memoir, he just about has it pat. Which says as much about the predominant tone of the chorus of voices in the book as it does about Tate’s ability as a surrealist: if these are unreliable narrators then they are ones for whom unreliability has become a matter of course; a gallery of deadpan fools whose voices feel mostly divorced from the archness of Tarquin Winot or the manipulative intelligence of Sarah Morton. If Deep Thoughts’ Jack Handy and poet Charles Simic found themselves trapped in a Max Ernst collage, the transmissions they sent out into the world beseeching our help might sound a little bit like Memoir of the Hawk. Take the narrator of “The New Love Slave,” for instance, who pays a visit to his new neighbors, a married couple with a little boy, “[to offer] them his services.” He and the husband Lee adjourn to the porch where apropos of nothing Lee says, “ ‘If you ever try to touch [my wife], I’ll kill you,’” to which the speaker responds, and continues to respond when threatened again, “ ‘I’m a happily married man.’” Back in the speaker’s house later on — where, it is pertinent to mention, there is no such wife in evidence — he muses how “this old neighborhood is in for some fun now,” while “[studying] Joan with [his] binoculars. Lee’s death…’” the speaker confides, “ ‘… will have to look like an accident.’” Here is mix between the criminally insane naivete of Lanchester’s Tarquin and the calculant opacity of Ozon’s Morton, with a hint of absurdity all its own. The unnamed speaker of the poem (almost all of the poems in Memoir of the Hawk have unnamed first-person speakers, both singular and plural) is no more reliable, at last, than the world he inhabits, where the rape dungeons of serial killers abut the white pickets fences of cozy nuclear families (the “new love slave” of the title implies that there are other “love slaves” in the background or waiting in the wings), and where neighbors threaten each other unprovoked beneath a veneer of samaritanism. Tate furthers this conceit in poems such as “The Black Dog,” which begins: “It was about two o’clock in the morning/ when the poker game broke up. Everyone was/ tired or drunk or broke. We were standing/ out on the lawn of Bob Blackburn’s house/ when this big black dog appeared out of no-/ where and started barking and hissing at us./ It was a mean-looking thing and it lunged/ at us as if it meant business…” When the confrontation escalates, Bob retrieves a shotgun and shoots the dog dead. The narrator says: “ ‘Jesus, Bob… That dog’s/ bit me three times before. But still…,’”/ “ ‘…a biting dog is not as bad as a/ killing man.’ No one spoke. It was a silence/ that signaled the end of something, poker,/ friendship, and something more. The unknown/ was already welcoming us into its secret heart.” One of the first things you notice, perhaps, is how implicitly the speaker misplaces the dog when it’s already “[bitten him] three times before.” Then there’s the speaker’s altered state: “drunk” and “tired” and in the dark. And then of course there’s that “unknown” which lurks at the “heart” of all James Tate’s creations. Unreliability resolves as the standard again and again and again in these poems. Unlike in Lanchester and Francois Ozon, the speaker’s off-kilter-ness doesn’t seep up but suffuses the narrative space all at once. The skewed meditations that make the collection, though they give the appearance of being a chorus, might well be outposts for the same roving psyche as the title, however obliquely, suggests — fragments of a consciousness that can no more stop moving than start making sense. If Lanchester’s novel is really a cookbook and the cookbook a memoir that makes a confession, and if Swimming Pool gestures at being film but is really a novel that breaks down the process by which its own narrative came into being, then Tate’s book transcends the real world altogether; it shirks materiality in favor of motion, of again and again taking flight through the void.

Alternative Cuts:

Atmospheric Disturbances by Rivka Galchen (2008); Enemy dir. Denis Villeneuve (2013); David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972)

Max Ernst: A Retrospective (2005); I Pity the Poor Immigrant by Zachary Lazar (2014); Gogol Bordello’s Super Taranta! (2007)

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov (1955); Grinderman’s Grinderman (2007); The Talented Mr. Ripley dir. Anthony Minghella (1999)

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson (1962); Diamanda Galas’ Diamanda Galas, aka Panoptikon (1984); Stoker dir. Park Chan-wook (2013)

The Imposter dir. Bart Layton (2012); Blood Will Out by Walter Kirn (2014); Johnny Cash’s Love, God, Murder Box-Set Compilation (2000)

NEXT TIME: Florida