Books & Culture

Telling Queer Love Stories with Happy Endings Is a Form of Resistance

Books and films about LGBTQ characters often focus on trauma. Shouldn’t we get a happy ending too?

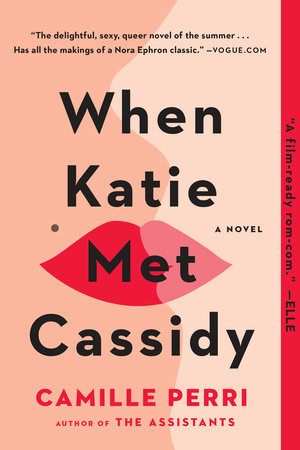

When people ask me what my new novel is about, I usually answer that it’s a romantic comedy about gender and sexuality — and specifically that it’s a love story between two women, one who’s more on the feminine side, and one who’s more on the masculine side. I generally don’t get into the nitty-gritty of why, exactly, I set out to write a novel like this. I don’t, for example, pull up a soapbox, stand on top, and pontificate about how even with all the progress we’ve seen over the years in relation to the LGBTQ community, so much of that culture remains invisible to America at large. And normally, I also don’t yell and scream about how frustratingly rare it is to engage with a story about LGBTQ characters that doesn’t involve death or illness or some identity-based misfortune. But as publication day approaches, and my book is still one of the few queer love stories that doesn’t end in disaster, I think it might be worth talking about why I did this — and why I hope I’m not the last.

During my lifetime, we’ve seen huge leaps in the quantity of LGBTQ stories that make it into mainstream representation — but the quality still leaves something to be desired. We see so many stories about the strife of coming out, the devastation it can wreak on relationships with family and community, the pain of living in the margins. But while those are important narratives to engage with — to peel apart so we can better understand the way the world works — the struggle shouldn’t always be the story.

We see so many stories about the strife of coming out. But the struggle shouldn’t always be the story.

I came of age on the LGBTQ stories available to me, which arose in the form of books I could get from the library: The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall; Rubyfruit Jungle by Rita Mae Brown; Stone Butch Blues by Leslie Feinberg. All of these hold a special place in my heart, but all of them feature main characters who suffer phenomenally on account of their gender and sexuality. Has there ever been a more self-explanatory title than The Well of Loneliness? Rubyfruit’s Molly Bolt, groundbreaking as she was for her time, still portrays a difficult to ignore hatred of masculine women. Feinberg’s Jess becomes a “stone butch” as a direct result of severe trauma.

For years I searched out movies starring women who fall in love: Foxfire; Bound; All Over Me. None of these films by any stretch of the imagination could be described as cheerful stories. Collectively they depict queer drug addiction and homelessness, excessive violence, and a prejudice-motivated death by stabbing. Even the satirical romantic comedy But I’m A Cheerleader, my favorite of the bunch and the closest any of the queer movies I discovered come to a happy ending, is centered on a conversion therapy camp to cure gay teenagers.

The recent movie Carol, based on Patricia Highsmith’s brilliant novel The Price of Salt, was a thrill to watch on a big screen and it sort of ends triumphantly, I guess, but still, one of the protagonists pretty much loses everything.

It just doesn’t feel like enough.

Where are the books and movies that convey the empowerment and joy that I feel attending the Pride parade each year, dancing in the streets to Lady Gaga or Madonna or Beyoncé, waving a rainbow flag like I just don’t care? In spite of what much LGBTQ media would have us believe, being queer doesn’t have to be a burden; it can be awesome. I highly recommend it.

My intention is to spread some of that around. I want to add value to the conversation and leave my mark by contributing in a positive way, with a happy story. That’s my wheelhouse. And I don’t care who doesn’t like it. (Straight white men, not everything is for you.)

LGBTQ people are people. We have the same ups and downs, highs and lows, as anybody else. So why should the stories about us always be about the bad stuff? We deserve the romantic comedy, the late night barfly scene, the silly, light-hearted stuff of life reflected back at us. Because the reality is, that’s as much a part of our lives as the sad stuff. So why wouldn’t that be reflected in fiction?

I’m hopeful we as a culture are on the brink of a new normal when it comes to depictions of diverse characters in situations beyond the tragic and gloomy. The recent romantic comedy The Big Sick, written by Kumail Nanjiani and Emily V. Gordon, is a notable example. The movie is about an interracial couple, but it was Nanjiani’s comment from the Oscar night red carpet that drove home what I consider to be their truly groundbreaking accomplishment. He said, “Emily, my wife, had this idea where she wanted to start a website called ‘Muslims having fun,’ which is just, like, Muslims eating ice cream and riding roller coasters and laughing and having fun. Because she gets to see that, and most of America doesn’t.”

I’d rather readers of my book get swept up in the fun of the story than take home any sort of political message. I want them to be too busy rooting for these characters, who may or may not be like anyone they’ve met in real life, to be aware of the underlying machinations of the novel. But the fact of the matter is, in the current social and political climate of our country, queer visibility is more imperative than ever. Our current administration can’t even be depended on to provide us with equal rights, never mind a sense of belonging. This was very much on my mind while composing this novel.

Happy gay art or entertainment, or art and entertainment about happy gay people, may not be about politics — but the fact of its existence is political. Just because a story is entertaining and funny doesn’t mean it necessarily backs away from serious issues. A celebratory queer love story in the midst of all the hatred and bigotry present in our daily collective conscious is, as far as I’m concerned, a form of resistance. An accessible, romantic comedy about two women that’s free from tragedy is in its own way radical.

A celebratory queer love story in the midst of all the hatred and bigotry present in our daily collective conscious is a form of resistance.

What has struck me over the course of this past year is that positive images are just as powerful as negative ones — if not more so. Conquering inequality doesn’t have to be achieved solely through struggle and suffering, and art and entertainment doesn’t have to be overtly oppositional to be subversive. Whether we’re conscious of it or not, positive images of people who are different from us are nourishing. I wish we lived in a world where depictions of Muslims eating ice cream and riding roller coasters and laughing and having fun weren’t so foreign to an American audience, but I’m glad as a culture that we are — at last — visibly moving in the right direction.

I don’t expect my queer romantic comedy to do much on its own to change the way the world at large views LGBTQ people. It’s more of a cumulative effect I hope to play a part in — a paradigm shift toward inclusivity that future generations will look back on as inevitable. Discrimination and bigotry won’t be defeated quickly or easily, but in the meantime we all deserve a happy ending every once in a while.